For most physicians, the only exposure they’ll ever get to clinical ophthalmology is during medical school. Unfortunately, the ophthalmology component of the undergraduate medical curriculum is limited and on the decline.1 Compared to other specialties, learning clinical ophthalmology requires more hands-on skills development, such as learning how to use a slit lamp, so this short but valuable time must be optimized to provide foundational knowledge to all medical learners.2 If you’re involved with any phase of training the next generation of physicians, this article will provide several helpful tips and insights on how to make the most of this formative, precious instructional time.

Establish a Foundation

There are many barriers that make the teaching experience either difficult or ineffective for both physicians and students. First, the lack of exposure to ophthalmology education steepens students’ learning curve. Moreover, in order to learn and retain the immense practical and technical skills comprising this specialty, there has to be constant, directed practice, instead of the more hands-off, theoretical approaches found in some other specialties. Lastly, the fast-paced, large-patient-volume environment in ophthalmology clinics limits clinical learning by restricting the time that’s available for teaching, providing feedback, skills observation and general orientation to the clinic.2

Interestingly, however, a comprehensive review of educational research on ambulatory education suggests that these barriers don’t significantly limit teaching effectiveness. Rather, it’s the specific behaviors and strategies of teachers that most impact the quality of the clinical learning experience.3,4

So, what are the impactful behaviors and strategies that ophthalmologists should emulate to optimize the learning environment? Here are three primary principles to keep in mind:

• Orientation and goal-setting. A brief orientation goes a long way toward fostering a good learning environment. The staff should ask students about their priorities, explain how the clinic works, provide a brief tour, and create a plan for the duration of the students’ stay. This will help make students feel welcomed, while anchoring them to the new territory they’re entering.

• Clinical immersion. The best way to make students feel engaged is to make them feel like they’re part of the team. Students should be introduced to all staff and patients, and be treated like valuable members of the clinic. Moreover, learners should be provided opportunities to showcase their knowledge and skills by being offered the opportunity to conduct clinical examinations—initially under supervision, and independently thereafter.

• Knowledge synthesis. To help students synthesize knowledge, staff can first ask them about their background knowledge to ascertain their baseline understanding of certain concepts. Then, it’s important to help the students draw connections between newly encountered clinical information and the theoretical information they already know. This encourages them to use their background understanding as a scaffold to bring fundamental ophthalmology concepts to life and apply it to clinical practice.

Teaching Strategies

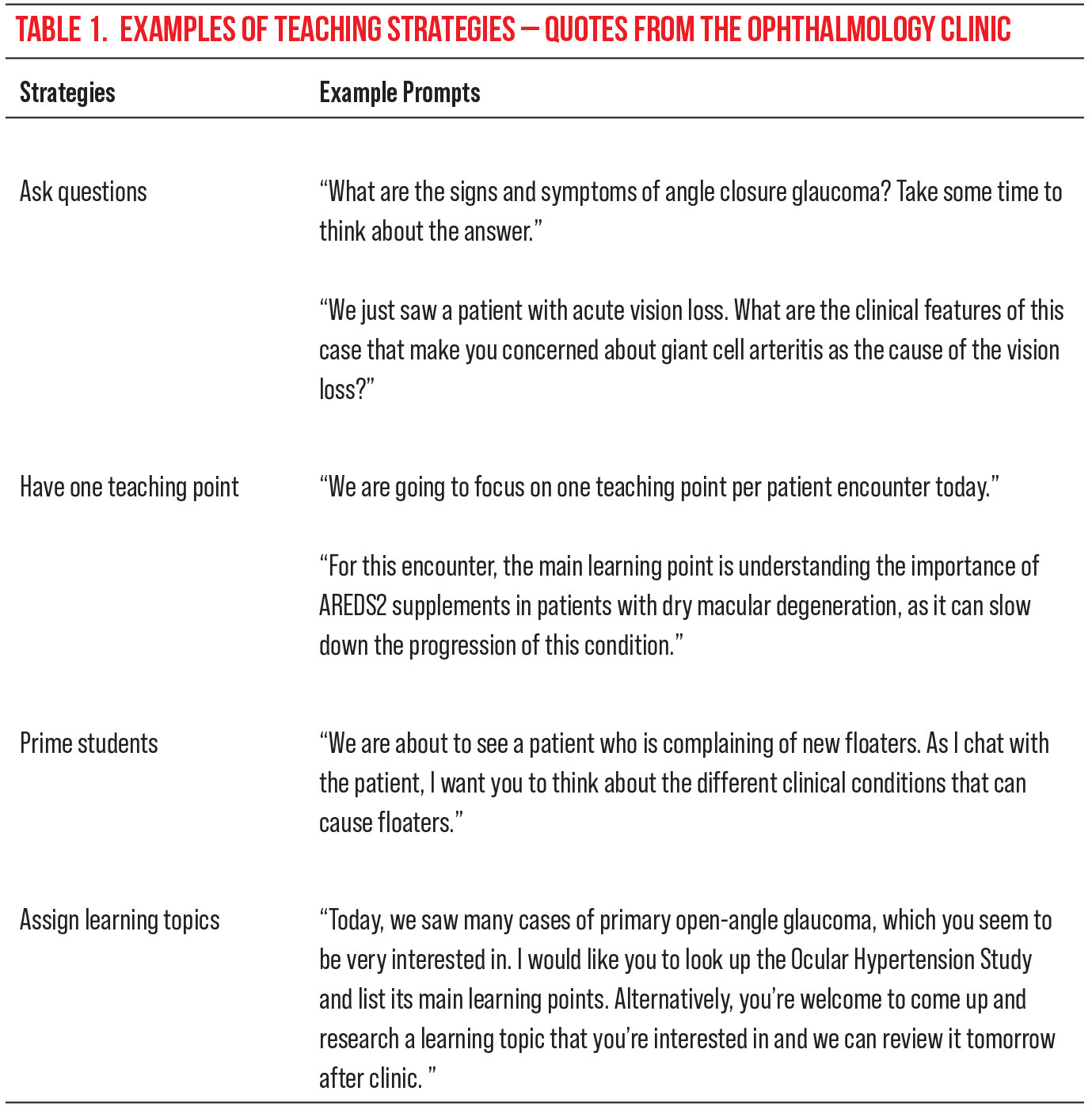

Clinicians should implement the three general principles listed above to inform their approach in mentoring students and building an environment conducive to learning. Once this foundation has been established, clinicians can then incorporate the following four strategies, adapted from a 1997 article by Seattle’s Steven McGee, MD, and his co-workers,3 to further optimize students’ knowledge integration:

• Ask relevant questions. Asking students questions is one of the best ways to evaluate and support their learning. Specifically, periodic questioning can help the students feel engaged throughout the rotation, motivated to enhance their knowledge, and help monitor their progress over time.3 Clinicians should provide learners with a minimum of three seconds to answer questions before interjecting. Evidently, prolonging response-time stimulates more insightful thinking, thus producing more reasonable answers.5

An example of a useful question might be, “This patient has optic neuritis. What are the clinical features of this condition?” or “We just saw a patient with a chemical injury of the right eye. If you saw this patient in the emergency room, what’s the most important treatment you could offer him/her?”

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

• Limit each patient encounter to one teaching point. It’s been shown that conveying one teaching point per patient encounter, rather than multiple, is much more valuable to students’ learning.3 Beyond a single teaching point, there’s an increased risk of overwhelming students and diluting the value of the teaching points. Ask yourself, “What’s the one point that’s most important to know for this case?” The teaching point should be brief and simple. This way, there will be greater emphasis on the most important take-home point, and it will be more likely to be remembered.

For example, you might say, “We just saw a patient with scleritis. The main take-home message from this encounter is that scleritis can occur secondary to an underlying autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis,” or “As you can see, the patient has multiple complex ocular conditions. However, what I want you to take away from this encounter is that graft-versus-host disease can affect the eye.”

• Prime your students. You can prime students before they enter the patient room by asking them a question relevant to the case. This is a valuable psychological technique that helps elicit relevant ideas in students’ minds before they face a clinical encounter.3 For example, before seeing a patient with photopsias, students should be prompted to think about the differential diagnosis for this condition. During the clinical encounter with patients, students’ minds will actively think of the differential for the case and evaluate the likelihood of each possible diagnosis. Priming helps prepare and steer students in the right direction, makes them feel much more engaged during the clinical encounter and consolidates their knowledge base.

As an example of priming a student, the instructor might say, “We’re going to see a patient with an orbital floor fracture. I want you to pay close attention to the physical examination maneuvers I perform when evaluating him,” or “Our next patient has primary open angle glaucoma. As I speak with her, I want you to think about the different imaging modalities we use in ophthalmology to monitor these patients closely.”

• Assign learning topics. Students coming to the clinic will undoubtedly have gaps in their knowledge. Though many gaps will be filled during clinical encounters, the remainder must be addressed outside the clinic. A great way to do this is to assign learning topics for the students to research and later review with the staff. The topics can be related to any concept in ophthalmology, but should be customized to each individual student’s needs, abilities and interests.

|

Ideally, assigned topics should prioritize common, high-yield foundational knowledge before diverging to more niche, advanced details. Staff should even consider asking students what topics they’d like to research, thus giving them greater agency in their learning and fostering a sense of responsibility. These learning goals should be discussed and reviewed later to address any further gaps in the students’ understanding, reinforce their knowledge base and commend them for their progress.

Such assigned learning topics often depend on the individual staff and what they believe are important concepts for medical students to learn. They also depend on a particular medical student’s knowledge level. Again, research topics should be on general, high-yield topics rather than small, niche “factoids” that medical students wouldn’t be expected to know.

Some common, high-yield foundational knowledge that medical students can learn more about independently are outlined below. Keep in mind that these assigned learning topics are broad but important concepts that medical students should know before graduating medical school (this list is not comprehensive):

— Glaucoma: What’s the difference between open-angle and closed-angle glaucoma?

— Retina: What are the clinical features of non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative diabetic retinopathy? How do you treat cases of proliferative diabetic retinopathy?

— Cornea: What are the differentiating features between a corneal abrasion and a corneal ulcer? How do you treat a corneal ulcer?

— Neuro-ophthalmology: What can cause papilledema? What type of investigations would you order when evaluating a patient with papilledema?

Overall, ophthalmology can be a daunting field for many medical students, and the medical school curriculum is unable to entirely address the gaps in learning that students have. Therefore, it’s up to clinicians to provide the foundational knowledge of clinical ophthalmology to students to develop their skills and competence in the field. To do this, effective teachers are paramount.

The principles discussed in this article constitute a core guide on how to teach ophthalmology. But ultimately, it’s up to each ophthalmologist to hone their teaching gestalt and recognize that every great surgeon must also be a great teacher.

Dr. Kwok is a resident, and Dr. Cao practices comprehensive ophthalmology, at the University of Toronto’s Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences.

Mr. Sidiqi is a medical student at the University of Toronto.

1. Noble J, Somal K, Gill HS, Lam WC. An analysis of undergraduate ophthalmology training in Canada. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 2009;44:5:513-8.

2. Succar T, Grigg J, Beaver HA, Lee AG. A systematic review of best practices in teaching ophthalmology to medical students. Survey of Ophthalmology 2016;61:1:83-94.

3. McGee SR, Irby DM. Teaching in the outpatient clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1997;12:2:S34-40.

4. Irby DM, Ramsey PG, Gillmore GM, Schaad D. Characteristics of effective clinical teachers of ambulatory care medicine. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 1991;66:1:54-5.

5. Rowe MB. Wait time: Slowing down may be a way of speeding up! Journal of Teacher Education 1986;37:1:43-50.