Early identification and treatment of primary angle closure suspects are crucial steps to help lower patients’ risk of developing glaucoma. The anatomical nature of their narrow angles will influence how they can be managed and how they respond, particularly if the patient has a plateau iris configuration. We spoke with several glaucoma specialists who offered advice on the clinical definitions and confirmation of narrow angles and plateau iris, treatment options and what to expect in long-term monitoring of these patients.

Differentiating Narrow Angles And Plateau Iris

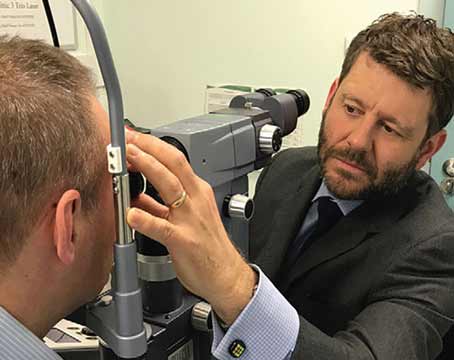

The first observation a comprehensive ophthalmologist makes is during a gonioscopy exam. They’ll notice the trabecular meshwork isn’t visible for at least half of the angle.

“For an angle to be classified as narrow, it must be occludable in at least two quadrants,” says Lauren S. Blieden, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at the Cullen Eye Institute, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. “This scenario describes what we refer to as primary angle closure suspect. In the case of primary angle closure the situation is similar, but patients also exhibit elevated intraocular pressure or findings of synechial closure or peripheral anterior synechiae on gonioscopy. Symptoms may vary from subtle complaints like new headaches with vision changes, such as halos around lights, to more pronounced manifestations like pain with blurred vision or full-blown acute angle closure attacks.”

The most severe condition in this spectrum is primary angle closure glaucoma, where there’s demonstrable damage to the optic nerve, anatomically or functionally characterized by visual field changes. “When distinguishing between narrow angles and plateau iris, it’s important to recognize that they fall on a clinical spectrum, with overlapping characteristics,” Dr. Blieden says.

Plateau iris will have a different appearance on gonioscopy. “Rather than exhibiting a typical bombe configuration—where the iris billows forward and occludes the pupil in primary angle closure—plateau iris displays more of an anterior rotation or anterior displacement of the ciliary body and the iris root,” she continues. “In this case, the iris root is pushed more peripherally into the angle because of the anatomical variations versus the iris simply bulging into the angle.”

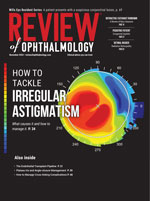

Many general ophthalmologists aren’t familiar with the diagnostic features associated with plateau iris. On gonioscopy, specific findings suggestive of plateau iris include the “double-hump sign” where one can see a ripple effect of the peripheral iris.

|

|

On gonioscopy, the iris bombe is the classic presentation of primary angle closure, where the iris billows forward and occludes the pupil. All photos: Sanjay Asrani, MD. |

“If the anterior chamber depth is deep centrally and narrow in the periphery, there’s a good possibility that the patient may have plateau iris configuration,” says James C. Tsai, MD, MBA, the president of the New York Eye & Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai. “The classic pupillary block type of angle closure suspect is a patient with a narrow central anterior chamber depth as well as narrow periphery. Observed very commonly in young patients with narrow angles, plateau iris configuration features an abnormal anterior position of the ciliary body. The entity is characterized by appositional angle closure with a flat iris configuration as compared to anterior bowing of the iris in the more typical angle closure glaucoma suspect patient. When the pupils are dilated, the angle gets crowded by focal bunching together of the peripheral iris, thereby causing an increase in intraocular pressure and an angle closure attack.”

Further confirmation can be obtained by ultrasound biomicroscopy, says Dr. Blieden. “Standard AS-OCT doesn’t penetrate beyond the iris; however, UBM can reveal crucial anatomical features that distinguish plateau iris from primary angle closure,” she says. “The definitive indicator of plateau iris on UBM is the anterior rotation of the ciliary body, accompanied by a notable loss of the ciliary sulcus space.”

Understanding patient risk factors will also help guide the diagnosis. “When I examine a patient with narrow angles, I think of the four major risk factors for angle closure besides family history: hyperopia; female sex; older age; and Asian ethnicity,” says Dr. Tsai.

Typically, patients with plateau iris syndrome present as narrow angles before age 40 and tend to be female.1 One way to confirm this diagnosis is following a laser iridotomy, the common first-line treatment for narrow angles. “After they undergo laser iridotomy, they may experience high intraocular pressure after dilation, despite the iridotomy,” explains Sanjay Asrani, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Duke University. “In contrast, those with narrow angles without plateau iris generally don’t have a pressure spike after dilation. It’s important to note that while some individuals over 40 may experience a pressure spike after dilation, they’re more likely to have a phacomorphic narrow angle, which is lens-induced.”

|

|

The “double-hump sign” is suggestive of plateau iris, showing a ripple effect of the peripheral iris. Accurate identification of plateau iris configuration influences treatment planning, say glaucoma specialists. |

Treatment vs. Observation

As mentioned earlier, peripheral iridotomy has been the standard therapy for narrow angles. However, there are differences of opinion on whether or not laser is always warranted.

First, Dr. Tsai says ophthalmologists must consider the true risk of the patient developing PAC or PACG. The ZAP study, a prospective, randomized clinical trial that compared LPI in one eye vs. observation in the contralateral eye of 889 patients with PACS, showed a low risk of patients progressing to PAC or acute PACG.2 Although the 14-year follow-up lost 390 LPI-treated eyes and 388 control eyes, PAC was found in two LPI-treated eyes and four control eyes.3

Using that same cohort of untreated eyes from ZAP, another study determined the baseline predictors of progression from PACS to PAC.4 They cited “higher IOP, shallower central and limbal ACDs, and smaller TISA at 500 µm and light-room ARA at 750 µm may serve as baseline predictors for progression to PAC in PACS eyes.”

Dr. Tsai provided a published commentary5 on this study, saying, “As a clinician evaluating a patient with bilateral, asymptomatic PACS (i.e., normal IOP, non-suspicious optic nerve examination findings [with OCT confirmation], no evidence of PAS on dynamic gonioscopy, and no history of an AAC episode), it’s comforting to know that the likelihood of that patient developing PAC or PACG is rather low based on the results of the large randomized clinical trials described here. In deciding whether to recommend prophylactic LPI or close observation in an asymptomatic patient with PACS, the ZAP trial results indicate that the clinician can make this clinical determination based on IOP, central ACD and limbal ACD without the need for more sophisticated AS-OCT measurements. In addition to the comprehensive ocular examination (including dynamic gonioscopy), patient factors such as age, sex, race, ethnicity and refractive status should be considered, since risk factors for the development of PACG include older age, Asian race, female sex, hyperopia and positive family history.”

Dr. Tsai says that if a patient has multiple risk factors but is asymptomatic, he will often consider performing the 15-minute dark room prone provocative test to obtain additional IOP information on these patients.

“In the dark room prone provocative test, the clinician records the patient’s IOP and then turns down the lights in the room,” he says. “The patient places their head down, and in the dark, their pupils should dilate. The clinician returns and measures their eye pressures after 15 minutes. This method is presumably positive (i.e., predilection for future angle closure attack) if the IOP is increased by at least 8 mmHG. If the IOP goes up by even 4 or 5 mmHg, that’s enough for me to be worried and strongly consider recommending laser iridotomy.”

Glaucoma experts say it’s important to discuss the success rates of LPI, as well as the side effects. It’s not uncommon for the patients to Google the procedure and find worst-case scenarios online, and ophthalmologists should be prepared to temper those misconceptions.

“Patients frequently express concerns about potential side effects following an iridotomy, particularly regarding dysphotopsias,” Dr. Blieden says. “While these visual disturbances can occur, they’re not as common as some might believe, and for the majority of patients, they’re not debilitating. However, significant findings from the EAGLE trial revealed instances of complications such as macular edema, persistent inflammation and uncontrolled IOP post-LPI. These complications sometimes necessitated further surgical interventions.”

If the angle remains closed post-PI, the next step has traditionally been iridoplasty. However, this approach is less frequently employed today, and clear lens extraction is becoming the preferred technique to eliminate the narrow angle issue altogether.

“If one is diagnosed with narrow angles, he/she may have plateau iris configuration, and a laser iridotomy won’t remedy and/or cure this condition,” says Dr. Tsai. “So in my opinion, you’re subjecting a person with normal vision, a normal optic nerve on OCT analysis, normal visual field, and no previous symptoms of angle-closure attack to an invasive laser procedure. What are the well-known risks of laser iridotomy? Well, these risks include bleeding, inflammation, ghost images, a keyhole effect and precipitation or worsening of a cataract.”

|

| Plateau iris presents with an abnormal anterior position of the ciliary body with the iris root pushed more peripherally into the angle. |

“The landscape of treatment has changed since EAGLE and ZAP, particularly with the realization that early cataract extraction can effectively open the angle in the majority of these patients,” Dr. Blieden says. “Thus, performing lens extraction has become a more favorable solution. In fact, it’s exceedingly rare for a plateau iris patient to not experience sufficient angle opening following cataract surgery. Some surgeons will combine lens extraction with endocyclophotocoagulation to help rotate the ciliary body down and away from the angle.

“In comparing groups from the EAGLE trial, it was evident that those undergoing laser iridotomy faced a statistically significant rate of subsequent glaucoma-related surgeries and interventions compared to the clear lens extraction group,” she continues.

Not everyone agrees that a laser iridotomy should be skipped, though.

“I generally don’t recommend clear lens extraction without prior laser treatment,” says Dr. Asrani. “This approach is unusual and could pose unnecessary risks. Laser iridotomy is essential to eliminate the possibility of pupillary block, and that may be all the patient needs. The success rate is very high for a laser iridotomy for narrow angles, and I feel that one shouldn’t bypass this part of the treatment process. Furthermore, one shouldn’t perform a clear lens extraction on a patient with normal IOP and an undamaged optic nerve. If a patient shows significant glaucoma damage to the optic nerve and is on maximum tolerated medical therapy but continues to progress, clear lens extraction can be considered, preferably after laser iridotomy has been performed.”

Close observational management can be a reasonable alternative, says Dr. Tsai. “I’m not saying it should be the only option. I believe it’s a reasonable alternative if patients desire a more conservative approach to avoid post-LPI adverse effects. However, if you as an ophthalmologist are concerned, you can always recommend the laser iridotomy procedure,” he says. “But please be on the lookout for patients with plateau iris syndrome since the laser isn’t going to solve the problem in these cases. Ophthalmologists should understand that if they perform successful laser iridotomy on a patient with plateau iris configuration, this patient will still be at risk of an angle closure attack with pupillary dilation.”

Patients who may not be candidates for conservative management could include diabetics who require an annual dilated retinal exam. “I wouldn’t recommend following this patient conservatively,” Dr. Tsai says. “I’d want to eliminate the pupillary block component of their narrow angles, and therefore I’d recommend performing LPI to minimize as much as possible the risk of angle closure attack (since the patient needs to have repeated dilated pupillary exams). In my opinion, the more times a patient with PACS gets dilated, the more likely they are to have an angle closure attack.

“Furthermore, alerting these patients to the utility of their smartphone flashlight and providing the potential benefits of immediate and bilateral pupillary constriction in aborting a suspected acute angle closure attack appears warranted,” he continues (see sidebar below).

|

Navigating conversations with patients about their treatment options really depends on the practitioner. “For patients who wear bifocals and exhibit signs of PAS or symptoms of angle closure, I recommend lens extraction,” Dr. Blieden says. “For younger patients who aren’t already reliant on bifocals, the discussion becomes more nuanced; they may be apprehensive about losing their ability to accommodate.”

For ophthalmologists who do choose to perform a clear lens extraction, Dr. Blieden says it’s essential for them to recognize that narrow angle cataracts behave somewhat differently from typical cataracts. “Be prepared for the possibility of shallow anterior chambers and understanding how the iris may respond intraoperatively, and the potential of a higher risk for aqueous misdirection during the perioperative period is crucial,” she says. “Additionally, awareness of the risk for myopic surprises due to the effective lens position of the IOL is vital during patient consultations.”

Overall, she says the findings from ZAP have helped calm her when approaching treatment for patients with narrow angles. “I no longer feel the need to panic upon identifying a narrow angle,” says Dr. Blieden. “We used to think they were a ticking time bomb for an angle closure. In reality, it just doesn’t happen that often, or that quickly. Instead, I believe in adopting a more cautious and measured approach, emphasizing patient education about their risk factors and treatment options. Keep an open dialogue and assess the patient’s anxiety level. Ultimately, it’s their decision, and it’s my job just to counsel them based on the evidence I have.”

Long-term Management and Ongoing Research

Dr. Asrani says there’s a misconception among patients that an LPI protects them for life.

“After laser iridotomy, it’s crucial to inform patients that although their pressures are initially normal, there remains a risk of developing chronic angle closure as they age,” he says. “The lens continues to grow and may lead to increased pressure over time. Therefore, patients should be advised to schedule annual follow-ups with their ophthalmologist or optometrist to monitor their optic nerve health and intraocular pressure. It’s important to convey that having had laser treatment doesn’t protect them from developing other forms of glaucoma, such as low-tension glaucoma.”

Dr. Blieden says she follows her clear-lens extraction patients similarly to POAG patients. “Historically, I’d schedule follow-up visits every six months; however, I’ve recently transitioned to annual visits,” she says. “I can’t completely let them go because we don’t know what those angles are going to do in 15 or 20 years. These patients are often younger—typically in their 50s—so as they age, particularly when they reach their 70s, we may not yet fully understand the long-term implications of their narrow angle diagnoses. The potential for increased risk factors over time is something we need to monitor, which is why annual check-ups seem reasonable until more data becomes available.”

Ophthalmologists should also keep tabs on their patients’ medications and which ones can cause dilated pupils. “Many subspecialties of medicine, including urology, psychiatry and ENT are realizing that their commonly prescribed drugs have anticholinergic properties,” says Dr. Asrani. “Just one extra medication, such as an antidepressant or decongestant, is sometimes all a patient needs to push them into a narrow angle attack.”

Dr. Tsai adds that Botox shots (botulinum injections) and over-the-counter cold medications that contain phenylephrine can cause pupil dilation, and scopolamine patches (for motion sickness) can cause long-term pupillary dilation (three days to two weeks). “Therefore, I stress to my patients that if they want to take a conservative approach with their narrow angles, they should avoid these medications,” he says.

The glaucoma specialists we spoke with are closely monitoring the research taking place regarding diagnosis and treatment for narrow angles. Dr. Asrani says he’s particularly interested in studies on imaging techniques that will help reduce the reliance on expert interpretation of gonioscopy.

“It’s a skill that many providers aren’t well-versed in,” he says. “Literature suggests that over half of newly diagnosed glaucoma patients don’t receive a gonioscopy, which could result in undetected narrow angles. Ongoing research is focusing on anterior segment optical coherence tomography and algorithms to improve diagnostic accuracy without the need for gonioscopy.”

Dr. Asrani reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Blieden consults for Alcon, New World Medical and Abbvie. Dr. Tsai is a consultant/scientific advisory board member for AI Nexus Healthcare, Eyenovia and Smartlens.

1. Jain N, Zia R. The prevalence and breakdown of narrow anterior chamber angle pathology presenting to a general ophthalmology clinic. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;18:100:24:e26195.

2. He M, Jiang Y, Huang S, et al. Laser peripheral iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure: A single-centre, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:10181:1609-1618.

3. Yuan Y, Wang W, Xiong R, Zhang J, Li C, Yang S, Friedman DS, Foster PJ, He M. Fourteen-Year outcome of angle-closure prevention with laser iridotomy in the Zhongshan Angle-Closure Prevention Study: Extended follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology 2023;130:8:786-794.

4. Yuan Y, Xiong R, Wang W, et al. Long-term risk and prediction of progression in primary angle closure suspect. JAMA Ophthalmol 2024;142:3:216–223.

5. Tsai JC. Longitudinal management of primary angle closure suspect. JAMA Ophthalmol 2024;142:3:224–225.