Anterior segment neovascularization results from several ocular and systemic diseases that predispose patients to retinal hypoxia and ischemia with subsequent release of angiogenesis factors such as VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor). Although angiogenesis is important in the development of embryonic and early postnatal development, in addition to endochondral bone formation, it is also a critical mediator for retinal and anterior segment neovascularization in eyes with neovascular glaucoma (NVG).

The best known anti-angiogenic agents of this class are the VEGF inhibitors such as bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech) and VEGF 165 (Macugen, OSI/Eyetech). This class of anti-angiogenic agents not only arrests the vascular endothelial cell proliferation and prevents vessel growth, but also induces regression of existing vessels by increasing endothelial cell death.

In February 2004, the Food and Drug Administration approved bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to VEGF, for intravenous administration in patients with colon cancer, in combination with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy regimens. A significant side effect seen with intravenous use of bevacizumab was arterial thromboembolic events, such as cerebral infarction, transient ischemic attacks and myocardial infarction. These events were fatal in some instances.

This medication has been used off-label systemically and intravitreally for management of subretinal neovascularization in macular degeneration and other disorders. I would like to share with you my experience with bevacizumab in the management and treatment of anterior segment neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma.

Case 1

A 62-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes and coronary artery disease presented with painless vision loss in the left eye for three weeks. Best-corrected vision was 20/20 in the right and count fingers in the left with a left afferent papillary defect. Intraocular pressures were 12 and 28 mmHg in the right and left eye, respectively. Retinal hemorrhages in four quadrants were present in the left fundus, venous tortuosity and macular edema. Gonioscopy OS revealed prominent neovascularization overlying the trabecular meshwork for 12 clock hours, without synechiae. A diagnosis of neovascular glaucoma secondary to central retinal vein occlusion in the left eye was made and laser panretinal photocoagulation was applied in several sessions over the ensuing three weeks (3,064 spots with diode laser). IOP was 46 mmHg despite use of 500 mg oral acetazolamide, and topical latanoprost, Cosopt and brimonidine. Synechiae developed over one-third of the angle with visible prominent neovascularization elsewhere in the angle (See Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Visible, prominent neovascularization in the angle. |

As a possible last resort prior to tube implant surgery, the patient was offered an off-label intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. Documented informed consent was obtained and 50 uL of bevacizumab (1.25 mg) was injected intravitreally without complication in the left eye.

|

| Figure 2. Total regression of angle neovascularization 13 days after the bevacizumab intravitreal injection. |

Two days after injection, neovascularization of the trabecular meshwork decreased substantially and IOP decreased to 18 mmHg on the same intensive medical regimen; optical coherence tomography demonstrated resolution of macular edema. Thirteen days after injection, the IOP was 17 mmHg without medications, with regression of angle neovascularization and macular edema (See Figure 2). Five weeks after injection, IOP was still 19 mmHg without medication and without any evidence of angle and/or iris neovascularization. Four months after injection, IOP increased to 28 mmHg with recurrence of neovascularization of the iris and the angle (See Figure 3). Glaucoma medications were started and more laser panretinal photocoagulation was performed.

|

| Figure 3. Recurrence of the neovascularization in the angle four months after the intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. |

Case 2

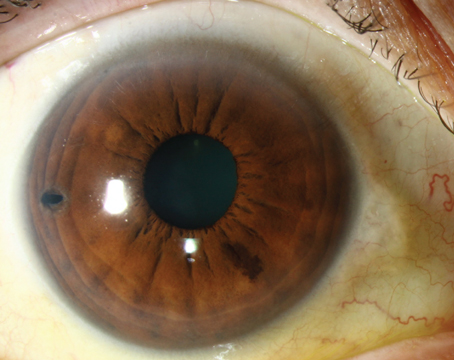

A 65-year-old female with hypertension presented with a history of decreased vision in the right eye for four weeks. Best corrected visual acuity was count fingers in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg in the right and 12 mmHg in the left. Anterior segment examination revealed neovascularization of iris, and gonioscopy revealed rubeosis of the angle for approximately four clock hours, without any synechiae (See Figure 4). Fundus examination revealed retinal hemorrhages in four quadrants, venous tortuosity and macular edema. The patient was diagnosed with central retinal vein occlusion and offered an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab off-label instead of panretinal photocoagulation.

After obtaining fully documented informed consent, 50 uL of bevacizumab (1.25 mg) was injected intravitreally in the right eye in an uncomplicated manner. The rubeosis in the angle started decreasing three days after the injection with total resolution in seven days (See Figure 5) after the injection, with IOP ranging between 10 and 15 mmHg. Two months after the intravitreal injection her IOP remained in the low teens with no recurrence of the rubeosis vessels.

|

| Figure 4. Visible neovascularization of the angle. |

Considerations for Future Treatment

Inhibiting angiogenesis is a promising strategy for the treatment of anterior segment neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma, if the angle is not totally closed from the peripheral anterior synechiae or damaged from the fibrovascular membrane. The neovascularization can recur if the ischemic process is not reversed. Several issues should be considered:

• Can bevacizumab become the only treatment for anterior and posterior segment neovascularization without the need for panretinal photocoagulation that destroys the peripheral retina in an individual who already has compromised vision?

Figure 5. Total regression of the angle neovascularization seven days after the bevacizumab intravitreal injection.

• The pharmacokinetics of the bevacizumab in the eye. (How long does it last and does it block all the VEGF at once or does it continue blocking until the antibodies are saturated?)

• Toxicity profile (corneal endothelium, lens and TM) and whether we can inject it in the anterior chamber instead of the posterior chamber.

Further investigations need to be performed to identify bevacizumab's exact role in retinal ischemia and neovascular glaucoma.

Dr. Al-Aswad is an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute. Contact her at (212) 342-0943 or laa2003@columbia.edu.

Other physicians who participated in the management of the two cases are: Michael J. Weiss, MD, PhD; Lucian Del Priore, MD, PhD; and Gaetano R. Barile, MD.