In this "In Practice" series, the editors at Review encourage ophthalmologists to take a second look at some technologies that are not new but may be of increased importance as ideas emerge in sur-gery and care. This month, pac-hymetry is the target, thanks to the movement of central corneal thickness into the sights of those seeking to identify risk factors for certain types of glaucoma.

Members of the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study group welcomed an unintended, but im-portant, result of their multicenter trial. The OHTS finding that having a relatively thin cornea is a risk factor for developing primary open-angle glaucoma came as an exciting revelation to many physicians. This new number in the equation, the central corneal thickness measurement, is going to determine the treatment path for many ocular hy-pertensive and glaucoma patients, predicts Dallas glaucoma specialist Ronald Fellman. "That piece of information [the CCT measurement] significantly changes how you evaluate and manage a patient," he says.

Where Pachymetry Fits In

The ability to create a corrected value for intraocular pressure affords the clinician a greater confidence in his assessment of a particular patient. "If the cornea looks healthy and it measures within the normal limits of thickness (around 540 µm), you can believe that the pressure read by the tonometer is reasonably accurate," Dr. Fellman explains.

|

| Pachymetry provides a new number in the glaucoma equation, the central corneal thickness measurement, which will influence a physician's decision to treat, or not. |

"If however," he continues, "the patient comes in with a pressure of

25 mmHg and the cornea measures 650 µm, then you know that the patient has a thick cornea and the applanation tonometer has overestimated the pressure." This is where the fudge factor comes in, says Dr. Fellman. "In general, we equate 1 mmHg for every 20 µm. That's a total guess, but it's the relationship we've decided to use, at least until somebody comes out with better evidence." Dr. Fellman suggests entering the corrected IOP in the patient chart in parentheses next to where the pressure measurement is normally written.

Target Patient Groups

The recognition of the utility of this test for glaucoma should not result in a rush to measure every patient's CCT, as in the context of a general screening. "Right now the best place to use pachymetry is in your glaucoma patients. I don't think it's a good screen for the general population," advises Leon Herndon, MD, of the Duke University Eye Center in Durham, N.C.

Dr. Herndon suggests that it is ap-propriate to do pachymetry on all glaucoma patients and glaucoma suspects, and Chicago physician Thomas Bournias agrees. He believes that the indications for performing pachymetry fall into three categories. He says that it is important to get corrected pressure readings on "a patient who has ocular hypertension with a normal nerve and a normal field, a patient who has a suspicious nerve with low pressure in order to see if the pressure is really higher than that which you are reading, and, third, on those pa-tients already diagnosed with glaucoma, so that you can feel confident in your treatment plan."

Dr. Bournias says that some ophthalmologists question the need to get a CCT measurement on a patient with confirmed glaucoma. The reason for doing it, he explains, is to establish a different target IOP based on the pa-tient's corneal thickness. He illustrates: "You may have two patients, each with a pressure of 25 mmHg and similar disc changes. If one has a corneal thickness of 480 µm and the other is 580 µm, their target pressures will be completely different because their corrected pressures are probably eight to 10 points apart, instead of being the same at 25."

"I'm asked if pachymetry should be considered a part of standard care in a glaucoma practice," says Dr. Herndon. "I think by far we do need to add central corneal thickness to our evaluation of glaucoma patients; no question about it." He says that, every day, he sees patients for whom the CCT measurement is invaluable. "We have the normal tension glaucoma patient who has been followed for years by her local doctor and is just getting worse, but her pressure has been in the normal range. So I see her and go to pachymetry and find she's got cor-neas of 420 µm, which is extremely thin. This measurement reveals that her pressure has really been in the 20s over that time period, and that's allowed me to become more aggressive with her treatment."

Finding a corneal thickness of more than 600 µm might cause a physician to dramatically alter the treatment plan; that is, to stop glaucoma treatment altogether. Dr. Bournias has done it himself. "In the past six weeks or so," he says, "I've actually withdrawn treatment on four patients based on normal nerves and thick corneas that I had been treating for the past year."

Ophthalmologists also owe their patients an explanation of how CCT could alter the course of their treatment. "It's wonderful to be able to tell a patient that her IOP is 5 mmHg less than it used to be, but you have to be able to explain what that really means," reports Dr. Fellman.

Importance Confirmed

"Glaucoma specialists have been talking about the importance of measuring corneal thickness for a number of years," explains Dr. Herndon. "Even in 1952, when Goldmann wrote his paper on applanation tonometry," adds Dr. Bournias, "he noted that 520 µm was considered the normal central corneal thickness and that any significant deviation from that figure would result in a different pressure reading." Studies announcing the importance of central corneal thickness have been in the American literature for at least the last 10 years, and in Europe, even longer, points out Dr. Herndon. "We've been measuring pachymetry on all new glaucoma pa-tients since at least 1997," he adds, "and on any patient who seems to be getting worse despite what we thought was good pressure control."

Awareness and Money

Buying or dusting off your pachy-meter and teaching your staff how to use it are your first hurdles, jests Dr. Fellman. "But determining how to assimilate the information into your practice, that's the more difficult part," he continues. "The CCT measurement is going to make you more likely to treat someone with a thinner cornea and less likely to treat someone who has a thicker cornea."

Ophthalmologists interviewed for this article agree that in spite of the value of using a corrected IOP to set up a glaucoma treatment plan, only a small percentage of physicians are routinely measuring CCT in the recommended populations. The reasons boil down to awareness and money.

"Coding is an issue," offers Dr. Fellman. "There has not been a standard Category I code for pachymetry." As a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology's health policy committee, Dr. Fellman re-ports that a code has been recently submitted for pachymetry. They ex-pect it will be accepted by January 2004. "When the ophthalmologist has a code, and he can get paid for the procedure, we will see the usage of it spread," predicts Dr. Fellman.

"In North Carolina, we have been billing for pachymetry for the past couple months. But I believe that even if you don't get paid for this procedure, it's worth doing it, for the pa-tient," asserts Dr. Herndon. "I can't tell you the number of times I am able to adjust therapy based on the corneal thickness."

While some physicians probably skip pachymetry because they don't have the equipment, Dr. Fellman also believes "that the majority who are not measuring CCT are not doing it be-cause they are unsure of what to do with that figure once they've got it. They're not exactly sure how to use it to fudge the pressure, and then they don't know how to use this corrected pressure in their management of patients."

To get the doctors on-board, Dr. Fellman recommends a multifaceted approach—peer pressure combined with scientific study. He encourages glaucoma specialists to get out into the community, to talk to generalists and spread the message that "there are a few groups of patients out there on whom you need to be measuring cor-neal thickness. This is who they are, and here is what to do with those measurements." Dr. Bournias also sees a place for teaching the utility of pachymetry for glaucoma in continuing education efforts. "More physicians will jump aboard as they see it in practice. Sometimes we can have material in the literature for years and it just takes time to get traction."

Technique Overview

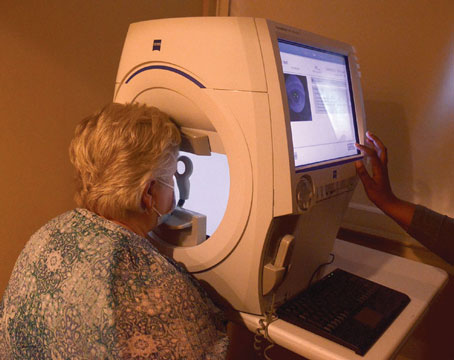

The purest cornea possible is what JoRhonda Williams, an ophthalmic technician who works with Dr. Bour-nias at the Glaucoma Service at Northwestern, looks for in her pa-tients. "I want to make sure that the cornea has not been touched," she says, "so I do pachymetry before tonometry, and definitely before the eye is dilated."

Dr. Fellman prefers to have the pachymetry done by the technician before he sees the patient. "The order of events that seems to work best is measuring CCT after the patient has had her acuity checked. Then, when she is seated in the exam lane for the doctor, that CCT number is ready."

Ms. Williams' first step is to make sure that the patient's eye is well lubricated. "With patients who have dry eye, I usually put in artificial tears before I begin," she counsels. "The more lubricated the eye, the better the readings." Her practice is supported by a poster presented by Dr. Herndon and colleagues at the 2002 annual meeting of the Association for Re-search in Vision and Ophthalmology, "The Effects of Drying on Central Corneal Thickness." This poster revealed that it takes only 15 to 30 seconds of not blinking the eye to significantly thin the cornea. "When a patient has numbing drops in her eye, she loses that blinking reflex," explains Dr. Herndon. "We instruct our technicians to make sure that the patient continues to blink, that he or she is not just staring for 30 seconds before the pachymetry is done."

As far as positioning, Ms. Williams tells the patient to keep still while she moves the probe directly toward the central part of the cornea. "I make sure I am in the center, and I have the probe parallel to the floor," she says. Ms. Williams takes three or four readings. If any are inconsistent, off by more than just a few microns, she throws out the odd one and takes a fifth reading. The average is the measurement that is used.

Dr. Fellman notes that not much will throw off a pachymetry reading, unlike A-scan biometry that can be confounded by a number of factors. He notes that a wide range in the values, even when the test is repeated, should be brought to the ophthalmologist's attention. "It's always fine to get someone else to recheck it." Dr. Herndon's leading caution is to make sure that the reading is taken in the center of the cornea, not in the periphery, where the reading will naturally be thicker.

As in Dr. Fellman's practice, technicians at Northwestern use a hand-held pachymeter. Both offices agree that a portable unit works best since it can be taken to the patient (instead of moving the patient) or to an outside clinic. Other sources recommend a foot switch and a choice of probe sty-les (angled or straight) for better control. Acknowledging that price is a big concern for many practices, Dr. Hern-don says that a pachymeter does not need a lot of bells and whistles; it should just be an ultrasound model ra-ther than an older optical pachymeter. "Pachymetry is not rocket science," he offers. "It's very simple."