After a Toxic Anterior Segment Syndrome outbreak last year in

An outbreak of TASS, such as the one that occurred in 2006, is an environmental and toxic control issue that requires complete analysis of all medications and fluids used during surgery, as well as a complete review of operating room and sterilization protocols.

As a result, the TASS task force determined several potential causes of the recent outbreaks and also drafted protocols with related industry and government agencies. Currently, the protocols are in the final stages of approval. Once available, these guidelines will help ophthalmologists and surgery centers in the prevention of TASS.

Classic Signs

TASS is a sterile, non-infectious acute postoperative anterior segment inflammation that is caused by a noninfectious substance that enters the anterior segment, resulting in toxic damage to intraocular tissues.

The signs of TASS often occur immediately after cataract/anterior segment surgery (12 to 24 hours after surgery). The typical hallmark of TASS is an inflammatory process that starts within 24 hours of cataract surgery. The infection is limited to the anterior segment of the eye, is always Gram stain and culture negative, and usually improves with steroid treatment. The primary differential diagnosis is infectious endophthalmitis. With infectious endophthalmitis, onset is on average between 72 and 96 hours after surgery.1

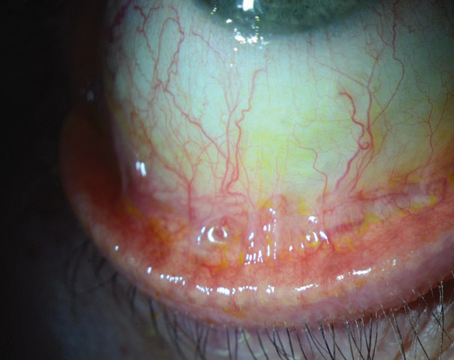

With TASS, patients complain of blurred vision, mild ocular pain and eye redness following cataract surgery. Inflammation is typically quite severe, usually resulting in a hypopyon formation, or a layering of the white blood cells in the anterior chamber. Diffuse limbus-to-limbus corneal edema is another common clinical finding of TASS. Although focal cornea edema sometimes occurs after cataract surgery, with TASS, it is diffuse and indicative of widespread endothelial damage.

In severe cases of TASS, it is not uncommon to see fibrin formation in the anterior chamber and/ or on the surface of the iris and intraocular lens. The syndrome can also result in permanent iris damage, which may cause a dilated pupil; an irregular pupil that constricts and dilates poorly; and/or potential trabecular meshwork damage.

Although TASS patients frequently may have decreased intraocular pressure in the early postoperative period, permanent trabecular meshwork damage may lead to ocular hypertension or secondary glaucoma afterward when the inflammation starts to decrease.

TASS Outbreak

I have been investigating TASS since the late 1980s. At that time, I was approached by the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery because there were sporadic reports of doctors who were having unexplained inflammation after surgery. I received funding fromASCRS and established the

Through the center, we developed protocols to determine the causes of TASS. A response team provides complete analysis of the surgical center and operating room and then provides recommendations to prevent future issues with TASS.

However, a marked increase of TASS across

TASS Taskforce

The task force included myself, Henry Edelhauser, PhD, from

The task force revised the TASS protocols and established a database to evaluate potential etiologic factors. This outbreak included more than 100 individual centers. The outbreak peaked in about April 2006, and by July 2006 the outbreak had abated.

Although all information was reviewed and analyzed, we found no data that pointed to a specific product as a cause. Therefore, we concluded that there was no single point source related to the outbreak. However, we did find multiple potential factors to be involved.

Potential Causes

While investigating the recent TASS outbreaks we determined that the causes were varied, including issues with sterilization, enzymes and detergents, preservatives, intraocular anesthetics and ointments, among other factors.

Today, as surgeons and surgical centers have become more and more efficient in performing cataract surgery, time constraints have lead to a shorter time available between cases for the adequate cleaning of instruments. For example, there often is not enough time to adequately clean reusable hand pieces and reusable instruments used in phacoemulsification. Although the manufacturers recommend that these hand pieces get flushed with 120 cc of fluid, it is difficult to achieve that level of flushing in between cases. This allows the possibility of residual cortex, viscoelastic or other materials left on the hand pieces that are not adequately flushed. If any of this residual material is left on the instruments, it can be flushed into the eye during the subsequent case, causing inflammation or TASS.

Therefore, to prevent TASS, protocols need to be followed to ensure that the staff is adequately flushing and cleaning the instruments (with sterile de-ionized or distilled water) in between cases. The task force also recommended that reusable instrument use be kept to a minimum, especially instruments such as small cannulas which are high risk for contamination.

Enzymes or detergents used to clean the instruments were another potential source of TASS. The task force noted that surgical centers used these enzymes or detergents to clean the instruments between cases and residual enzymes/ detergents left on the instruments could have caused inflammation.

This is especially an issue at multi-specialty surgical centers or hospitals in which ophthalmic and other surgical procedures are performed. At these centers, instruments used in a diverse array of surgeries are cleaned similarly. Unlike in ophthalmology, in other types of surgery (for example, a bowel resection) a large amount of tissue is often left behind on these specimens, and in order to clean the instruments, the hospital or the surgical center insists that enzymes or detergents are used.

The TASS task force has implemented an effort to educate multi-specialty surgical centers and hospitals as to how ophthalmic surgery differs from other types of surgeries in this respect. For ophthalmic surgical procedures, a large amount of tissue is not left behind on the instruments, and in fact, the use of enzymes or detergents could possibly cause inflammation, rather than prevent problems. Therefore, our educational messages emphasize that centers should not use enzymes and detergents and, if they are used, the instruments must be thoroughly flushed afterward.

In addition to detergent residues, outbreaks of TASS are thought to be related to endotoxin contamination of instruments during sterilization. Water baths, ultrasound baths and autoclave reservoirs may harbor Gram-negative bacteria if they are not changed and cleaned regularly. While Gram-negative bacteria are killed during the heat-sterilization process of autoclaving, heat stable endotoxins from the Gram-negative bacteria may remain attached to the instruments. The task force found that many surgical centers were also using ultrasound baths. The ultrasound bath must be thoroughly cleaned out after each use.

A TASS outbreak that occurred in late 2005 was found to have a single-point source. A specific brand of BSS was used in all of the cases and contamination of endotoxin was found. The product was subsequently withdrawn from the market.

Another major area the TASS task force looked at was different products used in intraocular surgery. We determined that when intracameral medications are placed in the anterior chamber of the eye, or into the BSS, it is important that they be preservative-free. There were several cases in which surgeons used epinephrine in BSS to help keep the pupil from coming down during surgery, and the epinephrine was stabilized by a bisulphate, which can be toxic.

Therefore, surgeons using any medications inside the eye should make sure they are preservative-free. Similarly, any anesthetics used inside the eye should also be the proper concentration and be preservative-free. For example, surgeons often use intracameral lidocaine at the beginning of surgery to help numb the eye. It is important that the lidocaine is preservative-free in order to prevent TASS.

Although no single type of IOL was associated with the 2006 TASS outbreak, there were questions with regard to residual materials that were discovered on the plunger and on the inserter of some of the reusable IOL inserters. Thus, these reusable instruments must be thoroughly cleaned, as well.

TASS Treatment

The main focus of TASS is on prevention, because once the toxic agent enters the eye and causes damage, the clinician can only suppress the secondary inflammatory response.

Once an infectious etiology has been ruled out, treatment for TASS consists of intense topical corticosteroids drops, such as prednisolone 1% (Pred-Forte), every hour with close follow-up.

Patients should be followed closely to make sure the inflammation is not worsening and the pressure remains stable. With careful slit-lamp examination, surgeons can document the resolution of anterior segment inflammation and corneal edema. When treating these cases, ophthalmologists also want to make sure that they remain comfortable that this is indeed TASS and not endophthalmitis.

After treatment, if the insult is mild, patients will tend to improve fairly quickly. There will be rapid clearing of the inflammation, the cornea will clear, and there will be no resulting permanent damage.

If it is a moderate toxic insult, there may be prolonged clearing (three to six weeks) with possible corneal edema or corneal damage.

However, if it is severe insult, the damage tends to be permanent. Most likely, there will also be corneal edema, (sometimes requiring a corneal transplant), sequelae of chronic inflammation, cystoid macular edema, and permanent dilated pupil. Patients with severe trabecular meshwork damage sometimes develop glaucoma that is resistant to medical treatment alone. These cases may require surgical treatment such as trabeculectomy or placement of a tube shunt.

Future Outlook

Because the mainstay of treatment for TASS centers on prevention, it is crucial that the entire surgical team (surgical nurses, operating room technicians, residents, physicians and pharmacists) know what is appropriate for use in the eye and be well educated about protocols.

During our task force investigations at various surgical centers, we realized that there were not adequate established protocols and guidelines in place for cleaning, processing and sterilization of instruments. For example, many surgeons we talked to were not aware of how the surgical instruments were being cleaned. The level and intensity of cleaning often depended on who was cleaning the instruments on different days. It became obvious that there were not good, established guidelines.

To increase awareness of TASS, the task force has taken several proactive steps to create educational materials, including a 40-minute video symposium that can be viewed at Tassfacts.com.

In addition, recommended protocols and guidelines have been established for the cleaning, sterilization and processing of instruments. Many organizations, including the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration, the

Dr. Mamalis is a professor of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences and director of the Ophthalmic Pathology Laboratory at the

1. Mamalis N, et al. Toxic Anterior Segment Syndrome J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:324-333.