Conjunctivochalasis is often overlooked in older individuals because its symptoms are very similar to those of dry-eye disease. The loose, redundant, nonedematous conjunctiva that characterizes the condition frequently disrupts tear production. It was first described in 1908 by Anton Elschnig,1 but the term conjunctivochalasis was coined in 1942 by Wendell Holmes, MD.2 Here, we’ll review the clinical findings, pathogenesis and management of this condition.

Clinical Findings

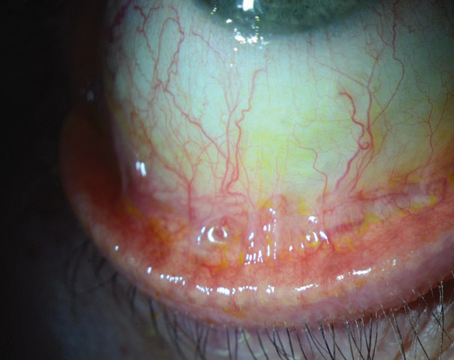

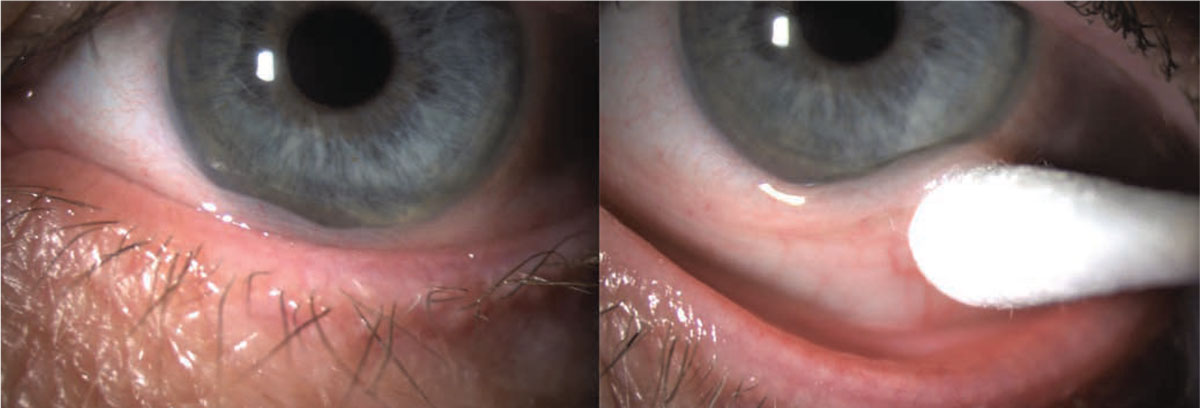

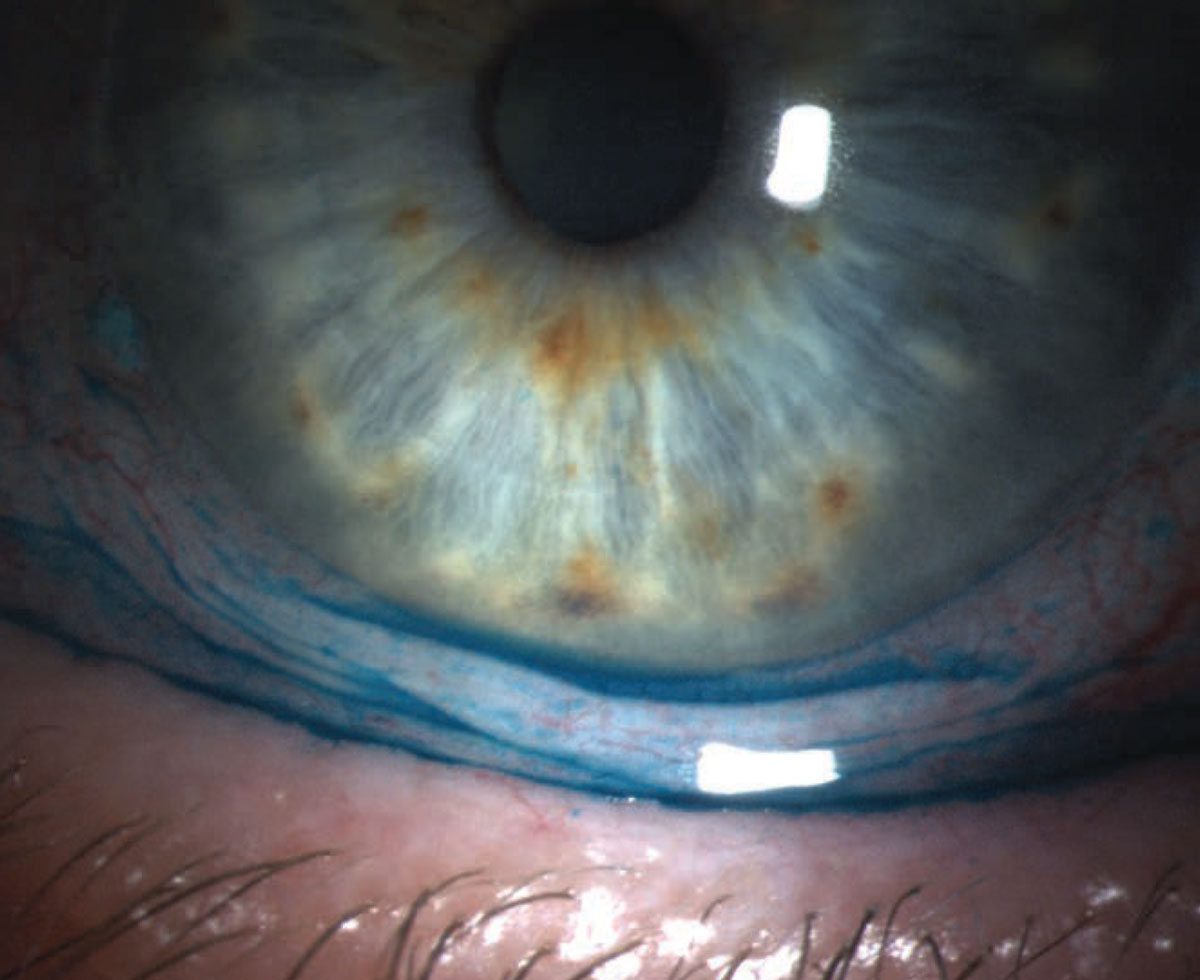

Conjunctivochalasis is characterized by loose, redundant, non-edematous conjunctiva. It’s typically found on the inferior globe (Figures 1 and 2)3,4,5,6 but sometimes occurs superiorly. The redundancy may be localized to one portion of the globe—either nasally, temporally or centrally—or span the entire inferior portion of the globe. When the loose conjunctiva folds over the lower lid margin, it’s easily seen and diagnosed.

|

|

Figure 1. Conjunctivochalasis of the inferior bulbar conjunctiva. |

The condition typically affects elderly patients, but can also be seen in younger patients. Women are more commonly and more severely affected than men. Bilateral presentation is most common, but it may also be asymmetrical and even unilateral.

Symptoms often include mild irritation, foreign body sensation, localized pain, tearing, blurred vision, burning, mucus discharge and nocturnal lagophthalmos. In the case of inferiorly located redundancies, the folded configuration of the conjunctiva at the inferior lid margin may cause disruption of the tear meniscus, reducing the spread of tears on the ocular surface and resulting in tearing. Epiphora may also occur secondary to redundant conjunctiva overriding the puncta, leading to punctal occlusion.

It’s important to note, however, that some patients may be completely asymptomatic. In these cases, it’s not unusual for mild conjunctivochalasis to be misidentified as a normal variant of dry eye and a result of the aging process. Dry-eye disease and conjunctivochalasis may also occur concomitantly, making it difficult to determine which condition to attribute the symptoms to. However, if the pain is worsened in downgaze or with blinking, conjunctivochalasis is the likely culprit. Additionally, the clinician can reproduce the pain of conjunctivochalasis by applying pressure on the lids over the area of the redundancy while the patient looks in the opposite direction.7

Besides the hallmark redundant conjunctiva, other examination findings include subconjunctival hemorrhage due to mechanical trauma from friction with blinking, unstable tear film, conjunctival injection from inflammation and lagophthalmos. The cornea may be clear or have punctate staining, as well as dellen formation adjacent to the redundant conjunctiva, or marginal ulcers.

Pathogenesis

The exact mechanism for conjunctivochalasis development isn’t known, but the literature suggests that it’s multifactorial.5,6 One thing we do know is that this condition is associated with pterygia and pingueculae. While older age plays a role in both pingueculae and conjunctivochalasis,8 the condition’s link to pterygia is thought to be related to dry eye and a shared association with inflammatory cytokines.9

Histopathologic studies are conflicting: Some have shown normal conjunctiva on microscopic evaluation10 and others have demonstrated degeneration of elastic fibers and chronic inflammation.11 Elastic fiber degeneration is seen in pingueculae, pterygia and photoaged skin, which suggests that conjunctivochalasis is induced, in part, by ultraviolet radiation.8,12

Also like pterygia, the conjunctivochalasis tissue itself has been shown to have increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases,13,14,15 which are enzymes that degrade matrix proteins. The tissue has also been shown to have increased reactive oxygen species that lead to oxidative stress.16 Why these develop is still unknown, but one hypothesis suggests that mechanical friction and dryness kick off an inflammatory reaction. The conjunctivochalasis tissue disrupts the tear film, which can cause tear pooling, either by disruption of the film or by punctal occlusion, which in turn provides a reservoir that prolongs the amount of time the inflammatory reaction is in contact with the ocular surface.5,6

Considering all of these factors, one can imagine conjunctivochalasis as a cycle that feeds upon itself, leading to the progression of the condition. Senile eyelid laxity may lead to dryness and friction that then induces an inflammatory cascade, including metalloproteinases and reactive oxygen species that damage the extracellular matrix proteins that ensure the conjunctiva adheres to the sclera. This leads to the conjunctiva hanging loosely and folding in on itself. In doing so, it creates more surface to undergo mechanical trauma with blinking, and that feeds back to create more inflammatory reactions. The resulting inflammatory reaction may also contribute to the symptoms associated with conjunctivochalasis.

Management

Asymptomatic patients don’t require treatment, but symptomatic patients should be trialed first on conservative medical management before considering surgical options.5,6,17 The goals of treatment are to smooth the ocular surface; restore the tear meniscus in order to improve tear-film stability; and reduce surface irritation and inflammation.

|

|

Figure 2. Conjunctivochalasis of inferior bulbar conjunctiva with lissamine green staining. |

These conservative measures primarily include ocular lubrication with artificial tears and lubricating ointments. If these treatments alone are insufficient to bring symptomatic relief, autologous serum tear drops, topical steroids, NSAIDs and antihistamines may also provide relief. Patients experiencing nocturnal lagophthalmos may benefit from nighttime lubricating ointment and patching to protect the ocular surface.

Coexisting ocular surface disease such as meibomian gland dysfunction, blepharitis and dry eye should also be treated accordingly. If other surface issues are left untreated, patients may remain symptomatic.

Surgical management can be considered for patients who haven’t responded to the above regimen. Numerous surgical methods have been described, and they can be broken into three main categories: shrinkage of redundant tissue; excision of redundant tissue; and improved adhesion of conjunctiva to sclera. These methods create a smoother ocular surface by eliminating or reducing the redundant tissue folds. With surgical procedures, the risk of cicatricial changes, symblepharon formation and shortening of the fornix are important risks to consider, as they can lead to worsening symptoms. Here are the options for surgical management:

Shrinkage of redundant tissue. Conjunctival cauterization is used to shrink the redundant tissue;18,21 it can also improve conjunctiva-sclera adhesion through coagulation. Conjunctival cauterization has been very successful in improving both symptoms and clinical findings related to conjunctivochalasis. After the procedure, patients may experience mild irritation, foreign body sensation, hyperemia, chemosis and subconjunctival hemorrhage—all of which are self-limited.

Some of the benefits of this procedure are that it can be performed with topical or local anesthesia, it doesn’t require sutures and it has a lower risk of infection, scar formation and restricted postop motility. Risks include symblepharon formation, cicatricial entropion and shortening of the fornix.

Shrinkage and coagulation of tissue can also be achieved with argon laser photocoagulation and radiowave electrosurgery.19 These have risks and benefits similar to cauterization and achieve similar results. Radiowave electrosurgery induces intracellular water boiling to shrink and coagulate the redundant conjunctiva and avoid charring of the tissue. This reduces the risk of scarring and enhances healing since there’s less thermal damage to tissues.

Tissue excision. The second surgical approach category is removal of the excess conjunctival tissue. This involves excision of the redundant conjunctiva.20 The tissue removed can be either localized to the area with the most clinical change or it can be done along the entire inferior bulbar conjunctiva.

Once tissue is removed, the wound can be managed in a number of different ways, including primary healing, suturing or gluing, and amniotic membrane grafting. Primary healing21 typically has a prolonged recovery time compared to other closure methods. It also has a high reported recurrence rate—24 percent—whereas recurrence rates with other surgical methods are reported to be zero percent.

With direct closure using absorbable sutures21,26 it can be difficult to determine how much conjunctiva to remove. If too much tissue is taken, the fornix may be shortened and cicatricial changes are likely to become more problematic. If not enough tissue is removed, the procedure may be non-therapeutic. The required sutures can prolong healing time, cause irritation post-operatively and lead to abscess or pyogenic granuloma formation.

Fibrin glue22 has been used in place of sutures. This reduces the risks of suturing and causes less postoperative discomfort. Another technique is to make a conjunctival incision, inject the fibrin glue, and then pinch and lift the conjunctiva to allow glue polymerization to occur. The surgeon then excises the elevated conjunctiva after the glue has set. Both methods have been shown to be successful.

Finally, an amniotic membrane graft can be used to cover bare sclera.23,24 The graft can be secured with fibrin glue or sutures to cover the bare sclera. Fibrin glue is associated with more postoperative comfort than sutures and reduces the infectious and inflammatory risks associated with sutures. Use of amniotic membrane grafting reduces risks of fornix shortening and limitations of ocular motility.

Conjunctival ligation is another option for removing the redundant tissue.25 This method involves drawing up the redundant tissue into a drip tube. Then, a suture is placed at the base of the conjunctiva and the tied-off tissue is excised. This method may lead to less postoperative discomfort than conjunctival resection with direct closure using sutures.

Improving adhesion. The last category of surgical methods aims to improve conjunctival adhesion to the underlying sclera. It includes scleral fixation with sutures or cauterization and amniotic membrane used to reinforce Tenon’s capsule.26 No conjunctiva is excised with these methods. Scleral fixation involves straightforward attachment of the redundant conjunctiva to the underlying sclera. For Tenon’s reinforcement, an incision is made in the conjunctiva and loose Tenon’s capsule is excised. The amniotic membrane is placed over the sclera and conjunctiva is closed over top. These methods reduce the risk of fornix shortening and ocular motility limitation.

In summary, conjunctivochalasis is a condition characterized by loose, non-edematous, redundant conjunctiva. The mechanism for pathogenesis is unknown, but is likely multifactorial and related to UV damage, mechanical friction and inflammatory reaction that leads to loss of tissue elasticity. Symptoms of this condition range from none to tearing, irritation and pain. Asymptomatic patients don’t require treatment. For symptomatic patients, conservative treatment is initially targeted at lubrication of the ocular surface. If conservative measures fail, surgical options include shrinkage of redundant tissue, removal of redundant tissue and increased adhesion between conjunctiva and sclera.

Samantha Marek, MD, is a resident at the University of Pennsylvania Department of Ophthalmology.

Stephen Orlin, MD, is the director of the Cornea Department, chair of the Cornea Service, co-director of the Refractive Surgery Service and an associate professor of ophthalmology at the Penn Presbyterian Medical Center of Philadelphia. They report no related financial disclosures.

1. Elschnig A. Beitrag zur aetiologie und therapie der chronischen konjunktivitis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1908;34:1133-1155.

2. Hughes WL. Conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol 1942;25:48-51.

3. Di Pascuale MA, Espana EM, Kawakita T, Tseng SCG. Clinical characteristics of conjunctivochalasis with or without aqueous tear deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:388-391.

4. Balci O. Clinical characteristics of patients with conjunctivochalasis. Clinical Ophthalmology 2014;8:1655-1660.

5. Meller, D, Tseng SC. Conjunctivochalasis: Literature review and possible pathophysiology. Survey of Ophthalmology 1998;43:3:225-232.

6. Marmalidou A, Kheirkhah A, Dana R. Conjunctivochalasis: A systematic review. Survey of Ophthalmology 2018;3:554-564.

7. Mimura T, Yamagami S, Usui T, et al. Changes of conjunctivochalasis with age in a hospital-based study. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;147:1:171-77.

8. Mimura T, Mori M, Obata H, et al. Conjunctivochalasis: Associations with pinguecula in a hospital-based study. Acta Ophthalmol 90:8:773-82.

9. Tong L, Lan W, Sim HS. Conjunctivochalasis is the precursor to pterygium. Med Hypotheses 2013;81:5:927-30.

10. Watanabe A, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S, Hino Y, Tsuchihashi Y. Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis. Cornea 2004;23:3:294-298.

11. Francis IC, Chan DG, Kim P, Wilcsek G, Filipic M, Yong J, Coroneo MT. Case-controlled clinical and histopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:302-305.

12. Tong L, Lan W, Sim HS, Hou A. Conjunctivochalasis is the precursor to pterygium. Medical Hypotheses 2013;81:927-930.

13. Li D, Meller D, Liu Y, Tseng SCG. Overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 by cultured conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts. IOVS 2000;41:2:404-410.

14. Acera A, Vecino E, Duran JA. Tear MMP-9 levels as a marker of ocular surface inflammation in conjunctivochalasis. IOVs 2013;54:13:8285-8291.

15. Guo P, Xhang S, He H, Zhu Y, Tseng SCG. TSG-6 controls transcription and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 1 in conjunctivochalasis. IOVS 2012;53:3:1372-1380.

16. Ward SK, Wakamatsu TH, Dogru M, Ibrahim OMA, Kaido M, Ogawa Y, Matsumoto Y, Igarashi A, Ishida R, Shimazaki J, Schnider C, Negishi K, Katakami C, Tsubota K. The role of oxidative stress and inflammation in conjunctivochalasis. IOVS 2010;51:4:1994-2002.

17. Mamalidou A, Palioura A, Dana R, Kheirkhah A. Medical and surgical management of conjunctivochalasis. The Ocular Surface 2019;17:393-399.

18. Haefliger IO, Vysniauskiene I, Figueiredo AR, Piffaretti JM. Superficial conjunctiva cauterization to reduce moderate conjunctivochalasis. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2007;224:237-239.

19. Trivle A, Dalianias G, Terzidou C. A quick surgical treatment of conjunctivochalasis using radiofrequencies. Healthcare 2018;6:14:1-5.

20. Petris CK, Holds JB. Medial conjunctival resection for tearing associated with conjunctivochalasis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;29:304–7.

21. Liu D. Conjunctivochalasis: A cause of tearing and its management. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1986;21:25-28.

22. Brodbaker E, Bahar I, Slomovic AR. Novel use of fibrin glue in the treatment of

conjunctivochalasis. Cornea 2008;27:950-2.

23. Georgiadia NS, Terzidou CD. Epiphora caused by conjunctivochalasis: Treatment with transplantation of preserved human amniotic membrane. Cornea 2001;20:6:619-621.

24. Meller D, Maskin SL, Pired RTF, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic conjunctivochalasis refractory to medical treatments. Cornea 2000;19:6:796-803.

25. Nakasato H, Uemoto R, Meguro A, et al. Treatment of symptomatic inferior conjunctivochalasis by ligation. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:e411-2.

26. Otaka I, Kyu N. A new surgical technique for management of conjunctivochalasis. Brief Reports 1999;129:3:385-387.