Surgeons say that even though intraocular lens dislocation at the time of surgery is rare, that’s all the more reason to keep your management skills for this particular complication sharp. Unfortunately, there’s no surefire technique for handling IOLs that won’t fixate properly, so surgeons have to use one that’s most comfortable for them, as well as be aware of the other options in case one of them turns out to be ideal for a particular situation. Here, cataract experts share their advice on handling these cases.

Common Causes

“Dislocation is often due to progressive zonulysis, and certain conditions predispose to that eventuality, most typically pseudoexfoliation,” says Samuel Masket, MD, in practice in Los Angeles. “However, an increasingly common etiology for late decentration of the capsule bag IOL complex is pars plana vitrectomy, either because of removal of posterior zonular fibers and/or a chronic breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier. In fact, any condition that has a breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier is likely to be associated with a progressive zonulysis.

|

Uday Devgan, MD, also from Los Angeles, says he considers the following in these cases: “How dislocated is the lens?” he asks. “Also, does it fall back into the vitreous when the patient lies supine? Should the current lens be kept or replaced? And, if the current lens is to be retained, how can it be secured?”

Keep or Replace the Lens?

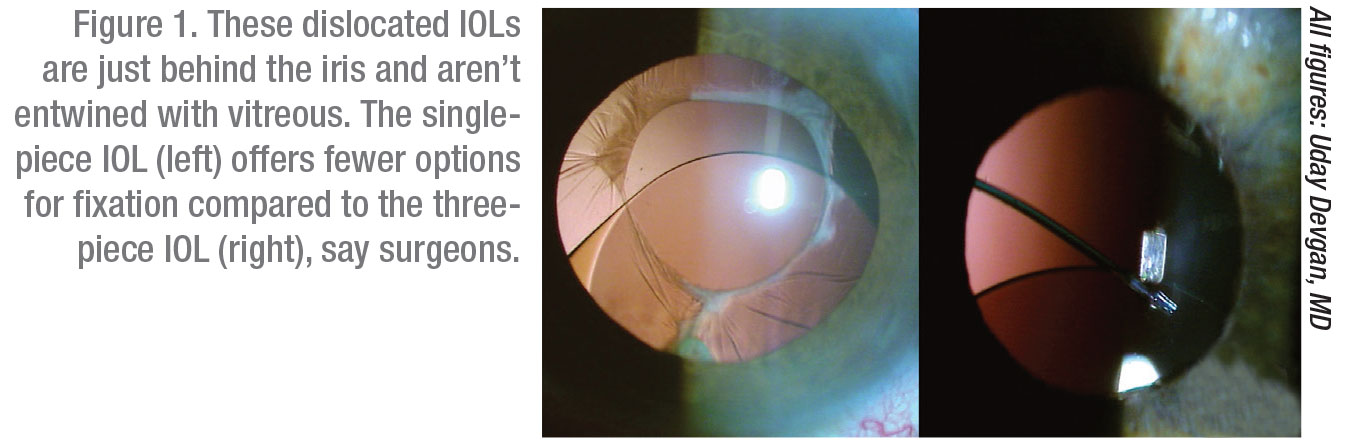

Dr. Devgan says that surgeons may want to keep the current lens if the patient has done well until the dislocation. However, if the lens is damaged, then it makes sense to exchange it. “When suturing a lens to the sclera or iris, it’s difficult to perfectly center the lens or align it with a toric axis. Therefore, for toric or multifocal lenses, it’s probably best to remove the lens and implant a standard monofocal lens, because monofocal lenses are more forgiving in terms of decentration or rotation,” he says.

According to Dr. Masket, the ideal approach is to keep the IOL inside the eye and fixate it in some fashion. “Among the skills that the surgeon needs to have available is an ability to re-open the capsular bag if the IOL needs to come out and the ability to stabilize or capture the IOL or IOL-bag complex by going behind it. This is done using the pars plana approach or by placing a safety basket suture, kind of like a tic-tac-toe board of 10-0 polypropylene as a safety net placed underneath,” he explains.

Securing the IOL

Dr. Devgan notes that IOLs are typically secured to the sclera or the iris. “If there is absolutely no capsular bag support, suturing the IOL to the iris is probably not a good choice,” he says. “It will probably need to be fixated to the sclera. If you choose iris fixation, the lens itself will be a big weight on the iris, and if there’s no capsule or any other tissue back there, the lens can shake too much and may eventually break off. With the sclera, there are many fixation options. IOLs can be sewn in or glued in, or we can use the Yamane technique.”

|

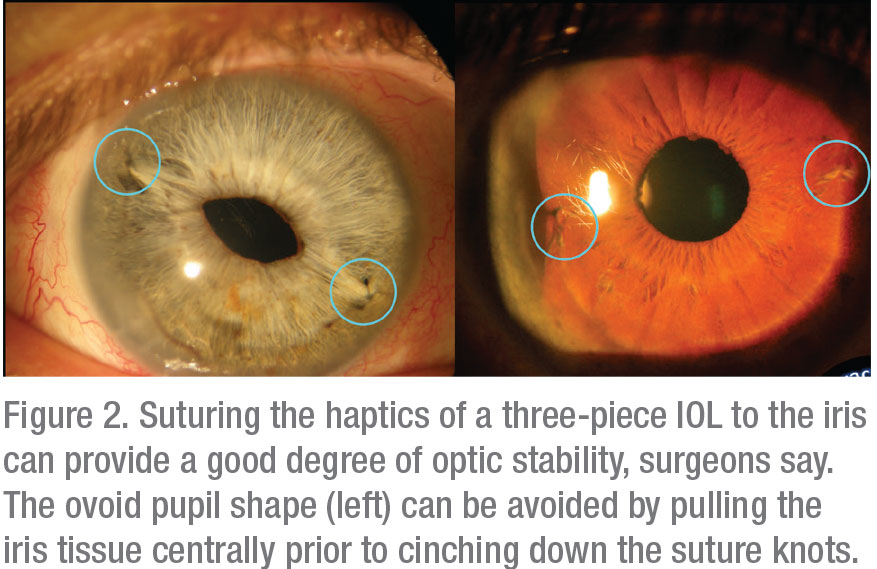

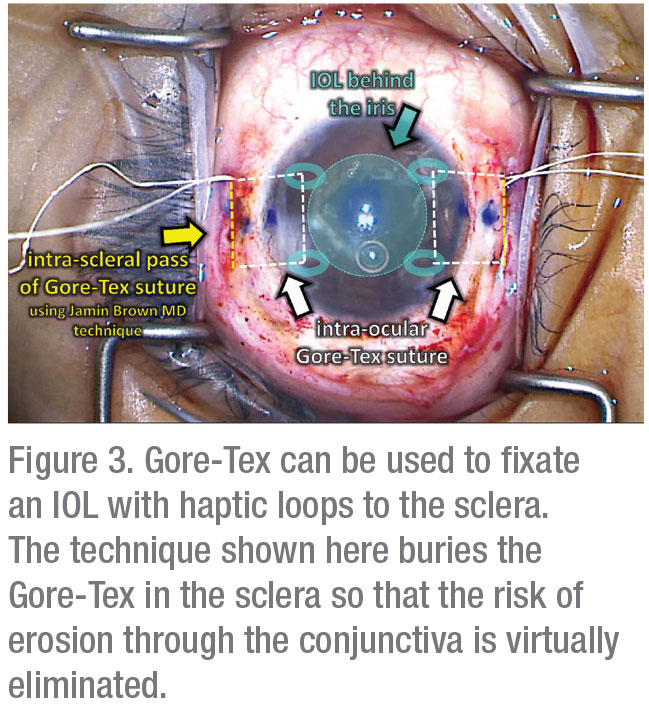

For suturing a haptic to the iris, Dr. Devgan uses 10-0 prolene. “This is a good choice because it will last and it’s in a protected space,” he says. “If you’re sewing an IOL to the sclera, there are two options: You can fixate the haptics themselves to the sclera using either the glued IOL technique where you make small tunnels; or you can use the Yamane technique in which you use a cautery to burn the end of the haptic to create a little bulb so it doesn’t move. I tend to use Gore-Tex if I’m going to suture a lens to the sclera. It works really well and has great long-term stability. It’s important to note that sewing a lens to the iris using the Yamane technique or the glued technique is off-label, and certainly using the Gore-Tex is off-label.”

An on-label option is to remove the dislocated lens and implant an A/C IOL. “A lot of these complex techniques aren’t easy, but placing an anterior chamber lens is relatively easy,” Dr. Devgan says. “Some surgeons recommend sewing a lens in, and they don’t ever implant an anterior chamber lens. However, studies have shown that anterior chamber lenses that are well-placed perform about the same as any of the suture-fixated lenses.”

Lance Ferguson, MD, from Lexington, Kentucky, considers the IOL material and the amount of scar tissue when planning his approach. “For dislocated but capsular-fixated IOLs, regardless of material, I can secure the IOL-capsule complex by encircling the haptic with a double-armed Gore-Tex suture placed at the haptic-optic junction and then fixate through the scleral wall. If the IOL is scarred down in the bag, then posterior support with a vitrector via a pars plana approach may be required to stabilize the IOL while driving the needle through the complex.

“If the dislocation is relatively recent with respect to the initial cataract surgery,” he continues, “then I viscodissect the IOL from the capsule, place a Cionni Ring or Ahmed segment, and recenter the bag by suturing it to the sclera, again with Gore-Tex. Another approach is to free the IOL from the bag, place it in the sulcus, and then suture to the iris with prolene. This works only for a three-piece IOL. Acrylic one-piece IOLs shouldn’t be placed in the sulcus or sewn to the iris. They should be partially bisected and removed in one piece.”

Dr. Ferguson also considers general anesthesia if the patient’s health doesn’t preclude it. If a patient is very old and won’t be able to withstand general anesthesia well, Dr. Ferguson recommends using an anterior chamber lens, remembering to perform a peripheral iridotomy at the end of the surgery. “This is for patients with a solid endothelial cell count,” he says. “It’s not ideal, but it may be the best solution for a very feeble individual who can’t undergo general anesthesia well or won’t be able to cooperate well during surgery.”

Santa Clara, California’s Huck Holz, MD, agrees that the type of lens is a consideration. “If it’s a three-piece IOL in the bag and it’s not completely dislocated, then I use a lasso suture. I have started using 8-0 Gore-Tex suture that I load into the lumen of a 30-gauge TSK large-bore needle, and I just thread it in. I then pass the loaded TSK needle 2.5-mm posterior to the limbus and underneath the haptic. I then retrieve the end of the suture through a sclerotomy located 0.5-mm anterior to my original needle entry with a micro-forceps. The other haptic is addressed in similar fashion. The suture is then tied and trimmed, and the knot is buried into the sclerotomy,” he says.

For one-piece IOLs that are in the bag and aren’t completely dislocated, Dr. Holz uses a lasso technique by passing 8-0 Gore-Tex suture threaded into the lumen of a 30-gauge needle around the haptic. If the capsule is really clean and devoid of lens cell proliferation and fibrosis, he performs an IOL exchange, removes the old lens, and places a Yamane fixated CT-Lucia lens. “If I already have to make a larger incision because I’m doing a DSAEK at the time of the exchange, then I’ll use the CZ70BD lens,” he explains.

For lenses that are hanging vertically in the eye when the patient is supine because there are so many zonules missing, he first identifies the quadrant where the IOL is located. This can be demonstrated by applying pressure to the sclera around the pars plana with a muscle hook. He’ll pass a 30-gauge needle through the pars plana where the lens is suspended by the few remaining zonules. “I’ll lift the lens with this needle, and then use the Gore-Tex suture fixation technique in which I cannulate the TSK needle with a Gore-Tex suture, and it ends up being a lasso suture fixation,” Dr. Holz says.

Dr. Holz notes that PMMA lenses that are in the sulcus and not the bag can be difficult to handle. “If I have no eyelet or fixation hole on the lens, then I remove it,” he says. “Because it has to come out through a 6.5-mm wound, I’ll replace this lens with a CZ70BD lens with sutured eyelets or use a Yamane fixation technique. If I have a dislocated PMMA lens that’s in the capsular bag, then I’ll use a Gore-Tex sutured lasso technique. If I have a PMMA lens with manipulation holes, I’ll thread them with an 8-0 Gore-Tex suture using micro-grasper forceps and secure the suture to the sclera. For dislocated plate-haptic intraocular lenses, I’ll generally exchange them, and I’ll do a Yamane lens fixation or use the other techniques that I discussed earlier.”

If a patient has a dislocated toric or multifocal IOL that’s in the bag, lasso suture fixation is best, if possible, some surgeons say. Careful toric alignment and multifocal centration are critical. If the lens isn’t in the capsular bag or is completely dislocated into the vitreous, then experts say these lenses must be removed. Dr. Holz recommends replacing them with monofocals.

Some patients are committed to the pursuit of re-implanting a multifocal. “l always advise against this,” warns Dr. Holz. “In a few cases, I’ve been able to achieve a very well-centered Yamane fixation of a three-piece multifocal platform,” he says. He says that this should only be attempted by surgeons who’ve done a large number of Yamane cases and can re-center lenses that are centering poorly intraop.

“The Achilles heel of Yamane fixation is intraocular lens decentration and tilt,” he adds, noting that the patient must be counseled preop that he or she will need a second refractive surgery to fine-tune induced defocus and astigmatism, because the tilt and effective lens position are difficult to predict.

Scenarios and Techniques

|

Dr. Ferguson recommends preparing for many scenarios before surgery. “Have your machine ready for a pars plana vitrectomy and gather some extra supplies,” he advises. “I like both the single- and double-eyelet Cionni rings. I like the Ahmed segments a lot, too. I use a double-armed Gore-Tex needle, which is a cardiovascular needle, and non-magnetized needle drivers, because if the driver is magnetized, it can be frustrating when fixating the needle; it can turn sideways or obliquely. An endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation probe is also nice to have. You can put it through a stab incision and look underneath the iris to see what you’re dealing with. That was really helpful in my initial Yamane cases because I wanted to see exactly where that haptic was going through the eyewall.”

For intact bags in which he’s using a Cionni ring, Dr. Ferguson will put the suture through the eyelet before implanting the device. “If you pre-place the suture through the eyelet, you save yourself a lot of difficulty,” he says. “One warning, though: If you do that and you’re using the Cionni ring, you can’t put it in a shooter. However, if you use a Bechert Nucleus Rotator, you can turn the rotator’s fork 90 degrees. If you just feed the Cionni ring in against that fork, it’ll slide right into the bag without a shooter.”

Dr. Devgan recommends taking the patient’s age into consideration. “I recently saw a 25-year-old who had severe trauma,” he recalls. The lens came out, he had no support, and I had to put in a lens with no easy way to secure it. I wanted to put in a lens that would last 60 years because of his life expectancy. I used Gore-Tex, which was buried within the sclera using the Jamin Brown, MD, technique, so that nothing was exposed. This will likely last for his lifetime.”

It’s also important to set and manage patient expectations. The original cataract surgery may produce a 20/20 result, but that shouldn’t be the expectation for a second surgery, Dr. Devgan says. “I tell patients they should be happy if they get half of their vision back after a second procedure,” he says. “Realistically, they can get 75 percent back, but I want to under-promise and over-deliver.”

He also recommends referring the case if you’re at all uncomfortable with it. “There is no harm in referring,” he says. “Some of the most talented people I’ve seen sew in lenses are retina surgeons. In my practice, if the lens is even a little bit entwined with vitreous, I refer to a retina surgeon.” REVIEW

None of the surgeons has a financial interest in any of the products or companies mentioned in this article.