Although trabeculectomy is being performed less frequently, I suspect most glaucoma surgeons would agree that when a patient has very advanced, rapidly progressive glaucoma requiring a dramatic pressure reduction, filtering surgery is still the fastest way to get that patient out of trouble. Most MIGS surgeries simply don’t have the pressure-lowering efficacy that a patient with advanced disease may need, and unfortunately, there’s still a lot of advanced disease out there. Those of us who primarily treat glaucoma see a lot of those patients, so we’re still doing quite a few filtering surgeries.

One of the primary reasons filtration surgery can produce mixed results is that there are so many uncontrollable variables in the surgery—factors that we can’t predict or manipulate. For example, we can’t control the integrity of the conjunctiva-Tenon’s complex, especially three, four or five years after the procedure. As a result, some blebs will break down; some will leak late; and some will fibrose very rapidly and fail. On the other hand, there are plenty of things we can control, so it’s important for us to be masters of those things.

Here, I’d like to discuss some of the issues surrounding filtering surgery and offer some strategies that will help produce the best possible outcomes for these patients.

Optimizing the Surgery

Intraoperative technique is one of the things within our control, and filters do sometimes fail because of poor technique. These strategies can help you avoid trouble.

• Before surgery, address any toxicity caused by glaucoma medications. Make sure the ocular surface is primed for a good surgical outcome. If the patient has a toxic surface because of aggressive medical therapy for glaucoma, pretreat the patient with steroids. If someone has follicular conjunctivitis because of an allergy to topical CAIs or brimonidine (the two most common allergies) you might want to stop the offending agent a few weeks before surgery to try to minimize inflammation on the ocular surface. Follicular conjunctivitis will doom a filter from the outset.

• Make sure the sclerostomy is adequate. A poorly executed sclerostomy will result in insufficient flow or too much flow—the latter making the patient hypotonous and problematic from the start. Experienced glaucoma surgeons respect and fear hypotony as much or more than elevated intraocular pressure.

• Perform meticulous wound closure. This is crucial for preventing perioperative wound leaks. Even with careful wound closure, small, transient leaks may occasionally occur at the incision site, but significant wound leaks early in the postoperative period should be very uncommon.

It’s true that we can’t control late leaks, typically caused by the conjunctiva breaking down. That’s partly because we have a catch-22 in glaucoma surgery: We have to use antimetabolites to prevent aggressive healing. Those antimetabolites may cause the tissue to break down over time, leaving us with problems several years down the road.

In the meantime, however, careful wound closure can prevent most immediate leaks.

Postoperative Management

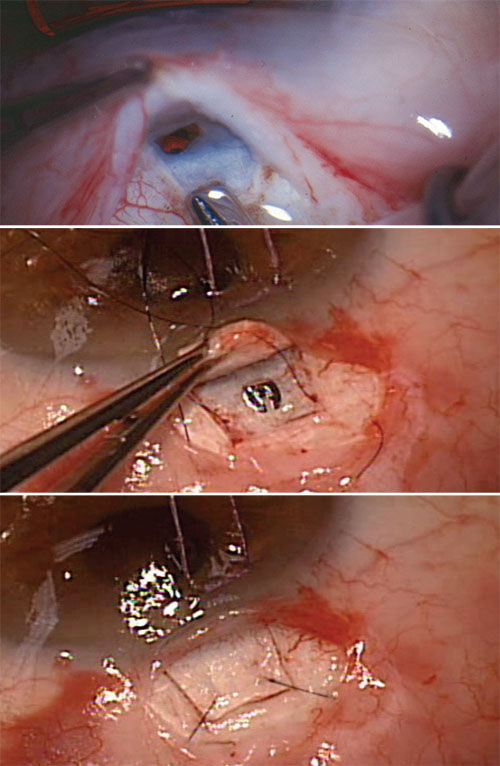

One of the nice things about trabeculectomy is that it’s titratable. We establish an outflow pathway and make sure there’s abundant flow; then we control that flow by how tightly we suture the scleral flap, and by suturing it in such a way that we can release the sutures later to allow additional flow as needed.

|

| Whether the sclerostomy is created manually with a blade or punch (top) or with a device (middle), filtration is controlled with sutures (bottom) that can be released or lysed to individualize care and titrate flow postoperatively. |

• Think carefully about the tim-ing of suture release. When to cut or release sutures is highly dependent on the severity of the glaucoma. How vascularized is the bleb? How low is your target pressure? How advanced is the glaucoma? Is the eye phakic or pseudophakic? How much does the patient depend on the surgical eye? (For example, if the other eye has no light perception, we have to be very careful not to put central vision at risk.) All of these things should factor into how aggressive we are with our surgery and suture releasing. Because of the multiple issues involved, it takes a lot of experience and surgical wisdom to time suture lysis and release correctly.

• You may want less flow at one day postop than later on. Some patients come into glaucoma surgery on multiple medications, and much of that pharmacologic therapy was intended to reduce aqueous production. In that situation the ciliary body may have been receiving the pharmacologic message to not make aqueous for years. Now we’re creating a new outflow system. If the outflow is overly aggressive and the ciliary body is still under the influence of pharmacological suppression, the result can be hypotony.

However, as the ciliary body recovers from the effect of those drugs, it will probably make more aqueous one or two weeks postop than it was making at postop day one. In these patients, the drain needs to be smaller immediately after surgery and larger at one or two weeks. Again, this is one of the advantages of doing trabeculectomy; we can titrate it as the ciliary body recovers from years of aqueous suppression.

|

• Optimize your use of postoperative steroids. I generally use a steroid up to four months, sometimes longer, after a typical trabeculectomy. (Note that the risk of increased IOP because of the steroid use is minimized by the bleb.) I suggest a minimum of three months for phakic eyes and four months for pseudophakic eyes. This is not because pseudophakic eyes have more inflammation, but because there’s no risk of cataract formation in a pseudophakic eye.

• Create a good bleb at every early visit. I like the patient to leave each postoperative visit with a pressure of 6 to 10 mmHg. If it’s postoperative day one and the pressure is 18, I’ll use localized or focal massage to generate a well-formed bleb to bring the pressure down. You don’t want the raw surgical surfaces, the Tenon’s conjunctival complex and the sclera, to be adherent; instead, you want a cushion of aqueous between them. So I want to generate a bleb each time I see the patient. If I find that I still have to do focal massage at each visit in the second or third week postop, I’ll cut a suture to increase the outflow.

• Be alert for bleb leaks. Leaks are bleb killers. If it’s a significant leak and the bleb is flat, do something to seal the leak so the bleb is regen-erated. If the bleb has been flat for a while postoperatively, it’s going to fail because there’s no potential space there. The conjunctiva will scar down and when the leak eventually seals, the potential subconjunctival reservoir has scarred down. So, fix leaks as quickly as possible to maintain the bleb.

• If all sutures have been cut and the pressure is still too high, use gonioscopy to see if the scleros-tomy is patent internally. If you find that the sclerostomy is not patent internally, take measures to clear the sclerostomy, such as YAG or argon laser iridoplasty.

• If all sutures have been cut and the pressure’s still too high, consider needling the bleb. Need-ling may help to salvage a bleb that’s threatening to fail early on. In many instances needling can prevent the patient from having to go back on medications.

Before needling the bleb, pretreat with neosynephrine to blanche blood vessels and minimize bleeding. Then, take a needle and probe under the bleb and/or scleral flap to see if you can reestablish flow. If flow is re-established, I may bring the patient back in several days or a week later to repeat the needling, this time ad-ministering antimetabolites. If I’m unable to reestablish flow, I’ll have the patient resume medical therapy.

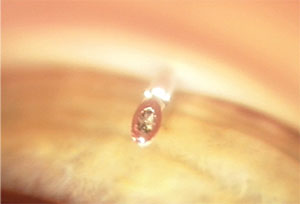

• If you use an ExPress shunt and the bleb fails, occlusion of the shunt could be the cause. I sometimes use Alcon’s ExPress shunt for filtering surgery; it helps me achieve very reproducible results, since the outflow channel is consistent. I find the ExPress especially useful in more elderly patients, or in individuals on anticoagulants. The downside is that it adds one more consideration if the bleb fails, because it’s possible that the device has become occluded with fibrin or inflammatory material. For this reason, I tend to not use an ExPress shunt in younger individuals or those prone to inflammation.

If the bleb does fail after implanting an ExPress shunt, it can be difficult to tell whether an occlusion is the source of the bleb failure. I’ve had several patients who maintained excellent pressure with the ExPress for several years; then they suddenly came in with high pressure. In this situation my first strategy is to needle the bleb. If that has no effect, I take them to the YAG laser and fire 2 to 6 mJ of energy up the lumen of the shunt; this frequently causes the pressure to drop dramatically. If that happens, I’ll treat the patient with an ongoing topical steroid to keep the blockage from recurring.

|

| Gonioscopic view of an ExPress implant with an obstructed ostium prior to applying YAG laser energy to re-establish flow. |

• Don’t skimp on follow-up visits. Make sure you see the patient in a timely manner. This isn’t “cut and forget” surgery; it requires careful postoperative monitoring. The reason this can be a challenge is that postoperative care is a lot of work, and it’s not reimbursed. To put it another way, the reimbursement is the same whether you see the patient five times or 20 times. It’s difficult to fill your clinic up with nonreimbursed visits, but it’s important to see these patients regularly to help ensure the best possible outcome. You just have to accept that it’s a lot of work.

Communication Counts

A good outcome often depends on getting patients—and in some cases referring doctors—to understand what needs to be done to minimize postoperative risks.

• Do what you can to make sure patients return in a timely manner. It’s not easy to convince patients that it’s important for them to come back weekly for the first few weeks; they may, for example, be dependent on a family member for a ride. It’s worth spending a little time to make sure the patient understands how important these visits are.

• Educate patients that they must always be alert for long-term complications, even though the risk is low. Patients are never completely out of the woods with filtration surgery; they can still have problems five or 10 years later. For that reason it’s important to educate them about that possibility. I always tell patients who have highly functional, pale, ischemic blebs that if aqueous can get out of the eye, bacteria can get in. That makes it critical for patients to take precautions against infection and understand the symptoms of infection. They need to be ready to take action if their eye gets red or they get a purulent discharge. In that situation they should be started on antibiotics immediately.

Some of my patients travel to third world countries or go to Mexico for spring break, and they can find themselves in situations where they can’t get medical care promptly. When I’m aware of such travel, I make sure these patients take a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone along with them on the trip. That way, if they develop a red eye, they can start the antibiotic empirically. It’s really important that these patients understand that they’re at risk for infection, even if it’s a small risk.

• Make sure referring doctors are on board with your management plans. High-quality postoperative care is time-consuming, and no one will work harder than you to salvage the bleb on a trabeculectomy that isn’t performing. So if you have to leave postoperative care to another doctor, the other doctor may not expend the energy needed to get the patient to the argon laser and cut a stitch. That’s especially true if it’s a hard suture to see or remove.

For this reason, as much as possible, we do our own postoperative care for our surgical glaucoma patients that live in our area. When patients come from the far reaches of the state, however, we may have to work with a local doctor. In that situation we do our best to convince the doctor that this is really important.

Unfortunately, this can have mixed results. For example, suppose a patient lives 300 miles away. I do the surgery and then I send the patient back home with a letter saying something like this: “I recommend a slow taper of steroid over three to four months. In addition, there are three scleral flap sutures that should be cut as needed to augment filtration. I rarely cut sutures during the first week, but I would strongly prefer performing suture lysis to putting the patient back on medications. Please let me know if suture lysis is required.” I even give the doctor my cell phone number to make it as easy as possible for him to contact me.

Unfortunately, what often happens is that despite laying all of this out clearly, the patient comes back six months later with elevated pressure, back on medications, and no sutures have been cut. Meanwhile, there’s been no communication from the other doctor. It may be that the other doctor just didn’t put the energy into trying to make this work; maybe he never even looked at the letter I sent. Then when the pressure rose he simply put the patient back on medications rather than doing the suture lysis or release.

This is very frustrating.

One thing that may help—depending on the patient—is explaining the situation to the patient. That way, when the local doctor suggests putting the patient back on medication, the patient might say, “Well, Dr. Samuelson said you might be able to open up the drain a little bit so I won’t have to use drops again.” Of course, not all patients will be able to understand and participate in that way, but some may be up to it.

Whatever happens, make sure that any communication breakdown doesn’t originate at your end. If someone drops the ball, make sure it isn’t you. REVIEW

Dr. Samuelson is a founding partner and attending surgeon at Minnesota Eye Consultants in Minneapolis and an adjunct associate professor of ophthalmology at Hennepin County Medical Center and the University of Minnesota. He is a consultant for Alcon, as well as several competing companies in the glaucoma surgical space.