Here, three retina specialists with extensive experience using these agents share the latest thinking about the pros and cons of using anti-VEGF drugs; the different treatment protocols being used; differences between the drugs; what to do when they don’t work; and what the future may hold.

Using Treat-and-Extend

“Today, the standard of care for a patient who has been identified as having wet macular degeneration is to treat with a potent anti-VEGF agent monthly until the patient is dry on OCT,” notes David M. Brown, MD, FACS, who practices at Retina Consultants of Houston, is clinical professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine and runs the Greater Houston Retina Research Center. “If you treat with any of these agents, even with aflibercept—which the studies suggest is probably the best drying agent—about 20 percent of patients still have fluid after three monthly shots. In that situation you just keep treating. If it takes 10 or 20 shots to dry them out, you keep going until they’re dry.”

“Once the eye is dry, you have a decision to make with the patient,” he continues. “You can try treating PRN, or you can begin a treat-and-extend protocol. Some patients—maybe 10 or 20 percent—dry out after several injections and don’t need any more injections for a while. If you’re willing, once the patient is totally dried out, you can choose to just watch the patient closely—see the patient at four weeks and six weeks and eight weeks and look for new leakage. Once you find leakage, though, you know the patient still needs treatment. At that point we typically begin treating the patient at an interval a little shorter than the amount of time that has passed since the last injection.”

Dr. Brown says that not all patients want to take this wait-and-see approach. “Most patients would rather start the treat-and-extend protocol at the beginning of their dryness,” he says. “If I’ve dried them out and the shot was four weeks ago, I’d say, ‘Let’s give you another shot and I’ll see you in six weeks.’ Then, when I see them six weeks later, I give them another shot and try extending the interval to seven weeks, eight weeks, etc., until they re-leak. If the patient re-leaks at nine or 10 weeks, I tell him that I’ll be treating him every eight weeks for the rest of his life. The goal in all of these treatment paradigms is to treat patients with the smallest number of injections that gives them the least amount of recurrent disease, leakage or hemorrhage. It’s unusual for a patient to dry out and stay dry over time.

|

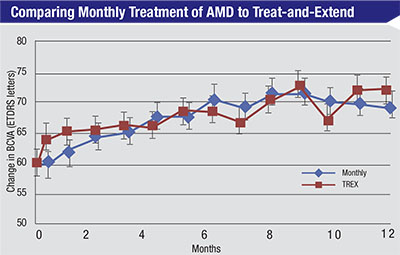

Patients in the TREX-AMD trial were randomized to receive intravitreal 0.5-mg ranibizumab either monthly or according to a treat-and-extend protocol. Mean BCVA gains were similar at 12 months (p=0.60).5 |

“Most of the time we do a fluorescein angiogram at the beginning, but sometimes we don’t,” he adds. “If it walks and talks and quacks like a duck, it’s probably a duck. On the other hand, if we treat with an anti-VEGF agent and it’s not getting better, we look harder. At that point, if we haven’t already done a fluorescein angiogram, we certainly do one then.”

According to Dr. Brown, a recent subanalysis of the VIEW studies by Glenn Jaffe, MD, and colleagues, [in press] found that only 20 percent of the patients still had fluid after three shots of Eylea, meaning they would probably need monthly therapy. “Of the patients in the Q8 arm of VIEW, 55 percent were dry at each visit, so another 35 percent of these patients probably needed injections more frequently than every eight weeks, but maybe not as frequently as monthly,” he says. “That gives you some sense of how many patients need this frequency of injection—at least with Eylea.”

Charles Wykoff, MD, PhD, a partner at Retina Consultants of Houston, co-director of the Greater Houston Retina Research Foundation and deputy chair of ophthalmology at the Blanton Eye Institute, Houston Methodist Hospital, also favors treat-and-extend. “My goal is to get the patient out to about 12 weeks,” he says. “Occasionally there are lesions that are well outside of the fovea on the periphery of the macula that I might choose to observe or laser, but in all other cases I start with monthly dosing and continue that until the macula is completely dry. The number of months that takes is variable; generally, larger lesions with more fluid at the outset take longer to dry out, although that isn’t always the case. Once the macula is dry, I typically pursue a treat-and-extend protocol.

Dr. Wykoff notes that fluid is not the only consideration. “At baseline I typically perform a fluorescein angiogram in the majority of my wet AMD patients,” he says. “If I have any suspicion of an alternate diagnosis, I also obtain an indocyanine green angiogram. If I get them out to a 12 to 16-week interval with treat-and-extend dosing and there is no evidence of recurrent exudative disease activity, I’ll repeat the fluorescein angiogram and evaluate the choroidal neovascular lesion compared to what it was at the beginning. If a lesion is present on angiography, typically I continue dosing the patient. If the lesion appears larger on the angiogram, then I have a discussion with the patient; I may decrease the interval to eight weeks to try to prevent further growth of the lesion, even if the OCT shows no fluid. Sometimes I don’t see much evidence of a lesion; maybe just some staining. In those patients I’ll have a discussion with the patient and sometimes try withholding injections and changing over to a PRN follow-up pattern, where I don’t necessarily inject the patient every time I see him.”

As far as clinical validation of the treat-and-extend protocol, Dr. Wykoff notes that evidence is limited. “We do have a few trials,” he says. “The largest treat-and-extend trial was the Lucentis compared to Avastin study, or LUCAS, a Norwegian-based study in which both arms were treat-and-extend; there was no monthly comparison arm. The only treat-and-extend trial that directly compared treat-and-extend to monthly dosing was TREX-AMD. This was a small trial—only 60 patients—but it appeared to show comparable outcomes between monthly and treat-and-extend dosing of ranibizumab. [See chart, p.25] Hopefully, in the future there will be a larger treat-and-extend trial that directly compares treat-and-extend to monthly dosing.

“One challenge is that we don’t have data on what to do with patients who are at a 12- to 16-week interval,” he notes. “Do they need to continue to receiving dosing indefinitely? Some of those patients stop getting injections and remain dry, but others will have a recurrence. Fortunately, some prospective trials are currently looking at this question.”

W. Lloyd Clark, MD, who practices at the Palmetto Retina Center in West Columbia, S.C., and is assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, believes most patients will probably need to stay on a treat-and-extend protocol long-term. “Given how difficult severe recurrences are to manage,” he says, “I think we’re looking at a need for chronic therapy in a large percentage of patients.”

The Issues Surrounding PRN

Dr. Wykoff notes that there are exceptions to his use of treat-and-extend. “If the eye dries out very quickly after one or two shots, and it was a small lesion to begin with, sometimes I will use PRN dosing,” he says. “In that situation I’ll observe the patient, usually at monthly intervals for many months, to see if exudative disease activity will recur. A small percentage of patients don’t need long-term anti-VEGF injections. We’ve learned this from all of the PRN trials—originally from PrONTO, but also from CATT and HARBOR. In my hands, fewer than 10 percent of patients require no additional injections once the fluid has dried out the first time.”

|

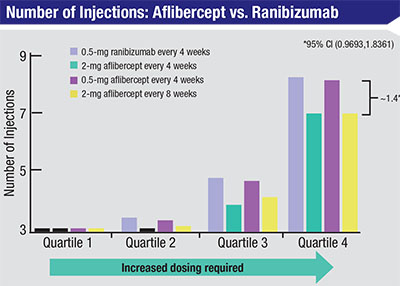

| Between weeks 52 and 96 in the two VIEW trials that compared intravitreal ranizumab to intravitreal aflibercept, among the eyes that had the greatest need for frequent injections (quartile 4), eyes receiving aflibercept required fewer injections than eyes receiving ranibizumab.6 |

“The PRN approach is, I think, acceptable if used one time,” says Dr. Brown. “In other words, if you think you may have dried the patient out, and everyone thinks that this is going to be the rare home run, letting the patient go without an injection is reasonable—once. But to require disease activity at every visit, to make an eye demonstrate fluid or hemorrhage each time before you treat, gives PRN a different meaning: ‘Progressive Retinal Neglect.’ When using PRN treatment, by definition, the patient has to get recurrent edema before you retreat. Using PRN repeatedly is very likely to lead to decreased visual acuity over time, and it gives you the highest risk of losing the visual gains the patient achieved with the initial loading doses. The other problem with PRN treatment is that it makes no sense unless your patient lives or works in your building, because you’re making him come in all the time looking for recurrences. If you stretch those observational visits out and you miss early recurrences, you have an even greater risk of trouble.”

Studies have found that after the initial monthly dosing, many doctors fall back upon PRN treatment and fewer injections. Dr. Brown says he understands why doctors would tend to shift in this direction. “I think both the doctor and the patient get fatigued by the protocol,” he says. “Doctors are certainly aware that patients would prefer to come in less often. On the other hand, most patients don’t want to go blind. So I don’t think you can make a good argument for any paradigm that leads to undertreatment.

“As with anything in medicine, you can look at it in terms of the risks and benefits of the therapy,” he adds. “The risk associated with an extra injection is the risk of endophthalmitis, which is about 1 in every 3,000 injections. The risk of a recurrence of the disease is 80 or 90 percent. So it seems to me that the pendulum should always swing in favor of a fixed dosing schedule determined by treat-and-extend.”

Which Drug to Use?

“All three anti-VEGF drugs can work very well,” notes Dr. Wykoff. “We have very good comparative da-ta from CATT and IVAN and other trials comparing Avastin and Lucentis, showing similar outcomes, although there are some signals from those trials that Lucentis may be a better drying agent than Avastin and may lead to a lower treatment burden over time. The only major head-to-head comparison data that we have for Lucentis and Eylea comes from the VIEW1 and VIEW2 trials, which were the registration trials that led to FDA approval of Eylea for wet AMD in the United States. Those trials compared monthly Lucentis and monthly Eylea, but there was also an arm that received Eylea every other month after three monthly doses. All the protocols turned out to have very similar efficacy in terms of visual acuity at the end of one and two years.” Dr. Wykoff adds that his preference is to start treatment with an on-label medication—i.e., Lucentis or Eylea. “However, in many cases we’re encouraged or mandated by insurance providers to start with the least-expensive option, which is Avastin,” he says.

“The general consensus is that most patients with new-onset macular degeneration will respond pretty well to all three agents,” says Dr. Clark. “Furthermore, it’s difficult to predict which patients might have a better response to any one of them. With that being said, my view is that there are patients who respond better to Lucentis and Eylea than to Avastin. Those are the eyes that have more aggressive disease, recalcitrant eyes that require more therapy. There is some anecdotal evidence about patients that have been on chronic therapy with Avastin or Lucentis switching to Eylea and improving, and there is some evidence from clinical trials that patients with the most severe, treatment-resistant wet AMD may respond best to Eylea. However, those recalcitrant, chronic cases probably only represent about 5 percent of eyes.

“Probably the best clinical data relating to treatment-resistant eyes is from the VIEW1 and VIEW2 trials,” he notes. “If you look at year two in the Eylea registration trials, a higher percentage of eyes in the Lucentis arm required numerous PRN injections compared to the Eylea arm. So eyes that needed a lot of treatment in year two were more likely to have been treated with Lucentis than Eylea. [See chart, facing page]. Of course, this was a small sample; there weren’t a lot of patients that needed a lot of treatment in year two. But if you add that to the anecdotal experience that many doctors have had, suggesting that the worst eyes tend to respond best to Eylea, I think it starts to tell a story for this small subset of patients.”

| Anti-VEGF and Geographic Atrophy |

| One of the concerns some surgeons have about the long-term use of anti-VEGF agents is the possibility that their use contributes to the development of geographic atrophy. “Whether anti-VEGF drugs influence the development or progression of macular atrophy is still unclear,” says Charles Wykoff, MD, PhD, co-director of the Greater Houston Retina Research Foundation. “Data from the CATT and HARBOR trials suggests that monthly dosing seems to increase the rate of growth of macular atrophy, with no consistent difference between the anti-VEGF drugs. However, it’s important to remember that undertreatment of active wet AMD leads to sub-optimal visual outcomes, as we first learned through the PIER trial, where patients were transitioned to quarterly dosing after three monthly doses. On average, patients lost all of their visual gains. A sub-analysis revealed that patients who maintained a dry retina during quarterly dosing also maintained their visual gains; those who had a recurrence of exudative disease on OCT lost their visual gains. So we have very good prospective data showing that the presence of fluid on OCT should be taken seriously and treated aggressively with ongoing anti-VEGF injections, even if we ultimately find out that the anti-VEGFs do play a role in accelerating macular atrophy.” David M. Brown, MD, FACS, who is clinical professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine and runs the Greater Houston Retina Research Center, says he doesn’t find the evidence of a connection between the use of anti-VEGF and geographic atrophy convincing. “Geographic atrophy happens in a lot of these patients with or without treatment, and it happens in fellow eyes,” he points out. W. Lloyd Clark, MD, who practices at the Palmetto Retina Center in West Columbia, S.C., believes the action of anti-VEGF drugs and the processes leading to geographic atrophy are independent. “I see geographic atrophy as part of the spectrum of dry macular degeneration disease,” he says. “Wet macular degeneration is a complication of the underlying dry macular degeneration, reflecting damage to the Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex, leading to neovascularization underneath the retina. I suspect these patients would be getting geographic atrophy whether or not they developed wet macular degeneration. “I can’t defend the idea of limiting anti-VEGF therapy in a patient with active wet macular degeneration because of concerns about geographic atrophy,” he continues. “If the patient has progression of the wet macular degeneration, or a subretinal hemorrhage or a retinal pigment epithelial tear, that’s clearly a worse clinical outcome than the slow progression of geographic atrophy. I don’t believe they’re related, and I don’t see the benefits of maximizing anti-VEGF therapy being outweighed by the potential progression of geographic atrophy.” —CK |

Dr. Wykoff believes the anti-VEGF drug a patient is treated with it less important than the treatment regimen. “No matter which drug is being used, the goal should be to achieve and maintain a dry retina,” he says. “Patients need to be treated on an individual basis. If they have fluid, they need to be treated aggressively. A study by Glenn Jaffe, MD, et al, that has been accepted by the journal Ophthalmology, looks at visual acuity outcomes in VIEW1 and VIEW2 with a focus on those patients who were consistently wet at the first four visits.1 Those patients gained significantly more visual acuity over the remainder of the trial if they continued with monthly Eylea instead of switching to every-other-month Eylea dosing. In fact, the FDA label for Eylea was recently clarified to specifically include that some patients do benefit from continued monthly dosing after the first three monthly loading doses of Eylea.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Wykoff says he isn’t convinced that one drug should be used exclusively in all cases. “In my clinic, regardless of which drug I’m using, I have a low threshold for switching drugs if I don’t feel that I’m getting a maximum response.”

When Anti-VEGF Doesn’t Work

Dr. Wykoff notes that it’s rare to find an individual who has no response to anti-VEGF therapy. “A significant number of wet AMD patients are recalcitrant,” he says. “We inject them repeatedly, but they continue to show fluid. However, that’s not the same as being a ‘nonresponder.’

“If the patient is a true nonresponder, then I have a low threshold for switching to a different anti-VEGF agent early on and/or looking for an alternative diagnosis,” he says. “Other processes can cause fluid in the macula, and it’s critical to rule those out in a nonresponder; I want to make sure I’m not looking at central serous retinopathy or IPCV. If the problem truly is wet AMD, I think almost all eyes will respond at least partially to anti-VEGF therapy. If the patient is responding partially, consider switching the patient to an alternate anti-VEGF agent and see if you obtain a better effect.”

Dr. Clark agrees that the first thing to do in this situation is exhaust all of the available approved anti-VEGF agents. “Whatever your initial drug of choice is, if you have a sub-maximal response after several months of monthly injections, move on to the next agent,” he says. “If that agent isn’t sufficient, try the third agent. You may have preconceived notions about which agent works better, but sometimes you’ll be surprised, so keep an open mind. Ultimately, you’ll find an anti-VEGF agent that’s effective with monthly therapy for more than 90 percent of patients.”

Dr. Wykoff notes another alternative: treating this type of patient more frequently. “In most cases I feel confident treating with anti-VEGF monthly, even in the presence of some persistent fluid,” he says. “The ones that I do treat more frequently are those that develop, for example, new intraretinal or subretinal hemorrhages while on monthly dosing, or those that show progressive macular edema despite monthly dosing—usually after having tried all three agents. As a result, I have a small number of patients who receive injections more often than monthly, a clinical approach that has been reported previously.2 Less than 1 percent of my wet AMD eyes need more than monthly dosing. Of course, care must be taken from an insurance-coverage perspective if using anti-VEGF injections more frequently than monthly.”

Dr. Clark notes that for the small percentage of patients that have an unacceptable amount of disease activity even with monthly therapy, treatment options are very limited. “Currently, we have no approved adjunctive agent to anti-VEGF,” he says. “There are a few new agents under investigation targeting other pathogenic proteins, most notably the anti-platelet derived growth factor, or PDGF agents, as well as some co-formulated investigational compounds.”

Dr. Clark says he believes there’s still a role for photodynamic therapy in a small number of patients who don’t respond to anti-VEGF drugs. “PDT is a good option for a patient who’s already had significant vision loss either due to chronic disease or other comorbid conditions, especially if treatment burden has become overwhelming,” he says. “PDT can inactivate the lesion, decreasing the treatment burden and maintaining the patient at a level of moderate vision loss, maybe between 20/80 and 20/200. On the other hand, if you’re managing a patient with very good vision who has persistent disease activity, it’s not clear to me that there’s a better choice today than continued anti-VEGF therapy.”

Dr. Brown believes that when a patient fails to dry completely with any of the available agents, the best option is to keep treating. “You really don’t have any other option, except ones that might interfere with macular visual acuity,” he says.

Issues Surrounding Avastin

As the least expensive anti-VEGF treatment option, many doctors start with Avastin (and insurers often insist on it). However, a couple of issues have arisen concerning the use of this drug in the clinic.

“One risk with Avastin is the need to use compounding pharmacies, which may introduce a small risk of endophthalmitis,” says Dr. Brown. “The bigger risk is variability in the availability of the drug itself. Anti-VEGF proteins in the drug aggregate to the walls of plastic syringes, and the proteins also denature with heat. In many cases, we don’t know how long the drug has been in the plastic vial.”

“Unfortunately, the Avastin that was used in CATT, as well as in the DRCR.Net Protocol T trial that compared Avastin to the other anti-VEGFs, is not the same Avastin that retina specialists have access to in community practice,” notes Dr. Wykoff. “The Avastin used in the trials was delivered in individual glass vials, whereas the Avastin used by most retina specialists is provided in plastic syringes. The process of compounding and storing bevacizumab in plastic syringes can result in high variability in its integrity and potency.3 That very likely has a significant impact on the biological activity of the drug inside of the eye. In fact, we don’t have any clinical data confirming that the Avastin that retina specialists use in plastic syringes has the same efficacy as the Avastin used in the head-to-head trials.

“Because of that,” he says, “if I don’t see a robust response anatomically when treating with Avastin, I have a low threshold to ask patients’ insurance carriers if I can switch to a more expensive on-label medication.”

Dr. Brown adds that a fair number of patients don’t dry out with Avastin. “In the CATT study, after very carefully searching for evidence of fluid, Avastin dried out 30 or 40 percent of the patients,” he says. “That means about 60 percent of patients would be switched to a branded drug, if it was possible for them.”

Managing Patients Long-term

“Long-term follow-up data from the CATT and MARINA/ANCHOR trials, at five and seven years after initiation of anti-VEGF therapy, respectively, are fairly sobering,” says Dr. Wykoff. “The visual gains achieved at the end of one or two years of intensive therapy were not maintained over three to five additional years of follow-up.” He notes that the reasons for this are not clear. “Were the eyes in both of these follow-up studies undertreated, meaning that wet AMD was the main cause of vision loss,” he wonders, “or was it that these eyes were developing concurrent macular atrophy? The incidence of that in the SEVENUP cohort was very high; 98 percent of patients had macular atrophy. In the CATT five-year follow-up analysis, the percentage was lower, 41.4 percent, but a substantial portion of the patients developed macular atrophy and that probably contributed to some of those visual declines.”

“At least two clinical trials have demonstrated that once we get away from protocol-based, criteria-driven treatment, trouble ensues,” agrees Dr. Clark. “In the CATT trial, we treated people on a criteria-driven, protocol-based schedule for two years. The patients did pretty well with all three agents, but after the two-year period they were left to the treatment of their own physicians. These patients were recalled at year five, at which point we obtained EDTRS visual acuity and collected OCT data. It turned out that all of the visual gains seen in year two were gone, and 80 percent of the OCTs showed fluid. In fact, the cohort lost, on average, eight letters by year five. Investigators were asked to count the number of injections they’d given from years three through five. They averaged five injections per year. So when you have significantly reduced treatments—in the neighborhood of one treatment every 10 weeks or so—all the visual gains are lost.”

Dr. Clark notes that the same thing happened in the Lucentis clinical trials. “The patients were initially enrolled into a variety of monthly treatment protocols,” he explains. “Then they were followed in a long-term study called HORIZON. In HORIZON, they were treated according to investigator discretion. Again, at the end of several years, all the visual gains were lost.”

Dr. Clark says that there is some good news, however. “Right now, I’m the principal investigator for a multicenter long-range follow-up to VIEW1 called the RANGE study,” he says. “We’re looking at protocol-based treatment of the patients who were initially in VIEW1 who went on to be part of the VIEW extension trial; they’re now in RANGE. We have five-year data based on criteria-driven therapy, meaning that we saw these patients frequently and treated them for any disease activity, rather than allowing treatment to become less-frequent. Our data shows that this approach has maintained the patients’ visual gains. It’s a very small cohort—only 35 patients—but it’s the first long-term protocol with anti-VEGF therapy to show maintenance of the gains.

“The take-home message is that if you maintain aggressive, long-term, disease-activity-based therapy, we believe you can maintain visual gains,” he concludes. “It’s clear that consistent dosing, even chronically, appears to be important.”

Strategies for Success

To help ensure the best results with the fewest difficulties, surgeons suggest following this advice:

• Make sure to get patients onboard at the outset. “The initial discussion with patients is critical, because with current technology you’re looking at a long-term treatment for most patients,” says Dr. Wykoff. “I often make the analogy to treating blood pressure. I point out that blood pressure medications work very well, but they’re not a cure for high blood pressure; if you stop taking them, the high blood pressure will likely return again. Similarly, we have really good treatments for wet macular degeneration today, but one of their shortcomings is that they don’t cure the disease. This helps my patients understand the need for ongoing injections.”

• Remember that treat-and-extend helps with patient throughput. “Aside from the fact that the evidence doesn’t support the use of PRN therapy, adopting a treat-and-extend approach adds efficiency to the process of managing these patients,” says Dr. Clark. “I’ve found that if you treat these patients PRN, they’re confused a lot of the time; they come in not knowing what’s going to happen. As a result, you often spend more time talking and relitigating the decision. If you use a fairly strict treat-and-extend approach with patients, they get into a rhythm and they understand what’s happening. When your patients come in, you know they’re getting an injection and they know they’re getting an injection. As a result, the workflow is relatively consistent, and the patients’ and doctor’s expectations visit-to-visit are consistent. Following this protocol also means most of these patients will come in less frequently than once a month, making it easier to manage more patients.”

• Don’t do a dilated exam every time an injection patient comes in. “If a patient needs more than six injections a year, I don’t think you necessarily have to examine the patient every time you see him,” says Dr. Brown. “I look at the OCT of the eye—and the fellow eye—because I want to catch fluid if it’s there. But I don’t perform a clinical exam (or bill for one) in some of the visits when patients are coming in routinely. I think it’s reasonable to examine this type of patient at least every two to three months, or if they have any new symptoms such as flashes, floaters, decreased vision or blurred vision, because sometimes you’ll find things you wouldn’t detect on an OCT. But from a patient-flow perspective and a patient convenience standpoint, it makes sense to skip the dilated exam at some visits.

“In our clinic we have what’s we call a ‘fast track’ or ‘über track’ for visits where I’ve examined a patient the time before and given her an injection,” he continues. “After an undilated OCT, we check the pressure and vision; then we prep the eye and do the injection and the patient is out the door. That allows me to get three or four quick patients an hour added to my regular schedule, and that really helps with the volume.”

Dr. Brown adds that these patients get express access to the OCT machine. “They basically go straight from the waiting room to the OCT, and then to a dedicated injection room. Many of these patients are in and out of the office in 30 or 40 minutes in one-third to two-thirds of their visits.”

• If you think a patient is not responding, check the patient before a month has elapsed. “The patient may have responded at one week after the injection, but the response wore off substantially by the time you saw her again,” notes Dr. Wykoff. “So if you think you have a nonresponder, it’s important to see the patient at a short interval after an injection.”

• Make sure your staff is well-versed in managing a large number of injection patients. “A well-trained, experienced staff can help to extend your efforts, in terms of education and patient management,” says Dr. Clark.

Relief May Be In Sight

With the baby boomers aging, the potential explosion in the number of patients with wet AMD has many surgeons concerned about the impact on their practices. Dr. Wykoff, however, believes this may be less of an issue than some fear, thanks to new technology still in the pipeline. “There are a lot of very exciting new therapeutic approaches currently in Phase II and Phase III trials,” he points out. “I believe these are going to significantly alter our treatment landscape and approach to treating these diseases.

“I see four major avenues under investigation,” he continues. “The first is novel anti-VEGF agents. Abicipar (Allergan) and RTH258 (Alcon) are both currently in Phase III trials ; the hope is that these new agents will prove more potent and/or have longer durability than the current anti-VEGF agents.

“The second avenue is agents that target complementary signaling pathways,” he says. “Blocking VEGF only impacts one growth factor. Other promising drugs under investigation block platelet-derived growth factor or angiopoietin-2, both being tested in combination with anti-VEGF drugs in human clinical trials being conducted by Genentech, Ophthotech and Regeneron. We’ve already seen positive clinical trial data from testing a simultaneous PDGF and VEGF blockade.4 Other medications under investigation as standalone approaches compared to VEGF blockade include ICON-1 (Iconic Therapeutics), an inhibitor of tissue factor. I suspect that some of these will be clinically available within the next two to five years.”

Dr. Wykoff says the third avenue under investigation is reservoir devices. “For example, Genentech’s ongoing Phase II LADDER study uses a reservoir placed through the sclera that slowly releases ranibizumab over time,” he says. “It might be possible to refill that reservoir a couple of times a year in the clinic.

“The fourth avenue is gene therapy and stem cells, and all of the associated derivatives,” he adds. “These are fascinating approaches with great promise, with limited data to date, that continue to be pursued.”

Dr. Wykoff also points out another development that could alleviate some of the in-office patient crunch: home monitoring. “Improving our home-monitoring systems so we can get photographs and OCT imaging of patients at home, to see if and when a patient converts to wet AMD or needs a treatment, could allow us to decrease clinic volumes across the country,” he notes.

Dr. Brown points out that we’ve come a long way when it comes to treating macular degeneration. “In 2004, if you weren’t in a clinical trial, you went blind,” he says. “Today, there are a lot of ongoing pharmaceutical trials and a lot of research and development taking place. Hopefully, we can continue the momentum we now have in fighting blindness.” REVIEW

Dr. Brown is a consultant for Regeneron/Bayer, Genentech/Roche, Allergan, Alimera, Alcon, Novartis and Thrombogenics. He has contracted research with Regeneron, Genentech, Allergan, Alimera, Novartis, GSK and Thrombogenics. Dr. Wykoff consults for and receives research support from Genentech and Regeneron, as well as numerous companies with related products still under development. Dr. Clark is a consultant for Genentech/Roche, Regeneron, Bayer and Santen and has received grant support from Allergan.

1. Jaffe GJ, Kaiser PK, Thompson D, et al. Differential Response to Anti-VEGF Regimens in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Patients with Early Persistent Retinal Fluid. Ophthalmology 2016; June 28. pii: S0161-6420(16)30320-7. [Epub ahead of print].

2. Stewart MW, Rosenfeld PJ, Penha FM, Wang F, Yehoshua Z, Bueno-Lopez E, Lopez PF. Pharmacokinetic rationale for dosing every 2 weeks versus 4 weeks with intravitreal ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept (vascular endothelial growth factor Trap-eye). Retina 2012;32:3:434-57.

3. Yannuzzi NA, Klufas MA, Quach L, et al. Evaluation of compounded bevacizumab prepared for intravitreal injection. JAMA Ophthalmology 2015;133:1:32-39.

4. Jaffe GJ, Eliott D, Wells JA, Prenner JL, Papp A, Patel S. A Phase 1 Study of Intravitreous E10030 in Combination with Ranibizumab in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1:78-85.

5. Wykoff C, Croft D, Brown D, et al. Prospective Trial of Treat-and-Extend versus Monthly Dosing for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. (Article in press).

6. Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kaiser PK, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninety-six-week results of the VIEW studies. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1:193-201.