and James R. Patrinely, MD

Traumatic laceration to the eyelid requires a thoughtful, well-planned approach in order to provide the best outcome and reduce the chances of postoperative complications. In this article, we'll review seven key steps that can help the eye surgeon achieve those goals.

1. Rule out occult injuries. Injuries to the face may be associated with intracranial trauma or other life-threatening problems. It is therefore imperative to first systematically clear the "ABCs" (airway, breathing, and circulation). Associated injuries such as a dissecting neck hematoma or laryngeal trauma can compromise the airway and aortic arch tears from blunt chest trauma can lead to sudden death. Palpate the orbital rim and facial bones for possible fractures that will require computed tomography. A complete eye examination should also be performed. For full-thickness upper eyelid injuries, be sure to check for globe perforations beneath the inferior limbus as well, since the Bell's phenomenon may bring this area into danger. Be suspicious of excessive chemosis (bland or hemorrhagic) that may indicate a hidden globe perforation.

|

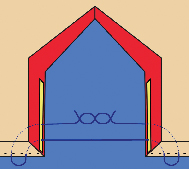

| Figure 1. Buried vertical mattress for full-thickness eyelid defects. |

The use of prophylactic antibiotics is controversial, but we generally cover with a first-generation cephalosporin against gram-positive organisms originating in the skin. For dirty wounds, wounds resulting from an animal or human bite, or in an immunosuppressed or splenectomized patient at risk for Capnocytophaga canimorsus (formerly known as DF-2) septicemia, we prefer broader coverage (such as amoxicillin clavulanate or clindamycin for the penicillin-allergic).

Tetanus prophylaxis may also be required.

Animal bite injuries must be managed according to rabies protocols and local reporting regulations, and in the case of a dog attack, the patient should be warned about potential recurrent attacks.1

|

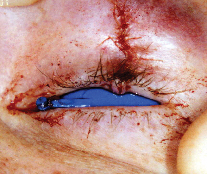

| Figure 2. Strong wound eversion and defect reapproximation utilizing the buried vertical mattress technique (6-0 polyglactin). |

In eyelid lacerations medial to the puncta, the canaliculi should be probed to assess integrity. We have found that most eyelid injuries can wait 24 to 48 hours, even up to a week, for soft-tissue swelling to improve or to refer the patient to a subspecialist, if necessary. Canalicular injuries repaired with silastic stenting maintain higher patency rates. Severed canalicular ends can be found by injecting air, fluorescein-dyed hyaluronic acid, or non-staining colored irrigant through the uninvolved canaliculus. The medial canthal tendon is essential for lid-globe apposition and for lacrimal pump function. Avulsion injuries of the posterior medial canthal tendon are fortunately rare, but should be repaired by suturing the tendon to the posterior lacrimal crest.

4. Anesthesia considerations. We prefer general anesthesia or deep monitored anesthesia care for complex lacerations involving the canaliculi, underlying bone fractures, and when operating on young children. Local anesthetic with at least 1:100,000 epinephrine can be used judiciously, to lessen bleeding, but care should be taken to not inject vascularly compromised flaps.

|

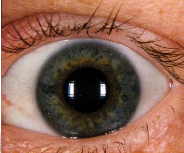

| Figure 3. Nine-month postop photo of the same patient showing acceptable aesthetic and functional result. |

We perform primary repair of the levator aponeurosis by repositioning it to the upper half of the tarsus with permanent 6-0 or 7-0 suture material. Suturing of the disinserted levator too inferiorly on the tarsus can result in poor lid-globe apposition.

The orbital septum should never be repaired, as this may result in compromised eyelid excursion and even lagophthalmos. Therefore, caution is needed to avoid suture incorporation of the septum during eyelid laceration repair.

Injury to the anterior lamella (skin and orbicularis) can be closed in layers, if wounds are stepped, or as a combined unit with simple interrupted or a running 6-0 to 7-0 sutures along the cutaneous skin defect. Interrupted sutures may allow for hematoma egress or infection drainage, although both of these complications are rare. In children or patients unlikely to return for postoperative care, absorbable suture such as fast-absorbing plain gut works well. Otherwise, we prefer a permanent suture material, such as prolene or nylon. Lacerations in the forehead and thicker facial skin may benefit from a combination of interrupted 5-0 and 6-0 sutures. Steri-strips are used to support all non-mobile wound repairs.

6. Tarsal and full-thickness eyelid repair. Disruption of the tarsus from the lateral canthal insertion can be repaired using a 4-0 to 6-0 polyglactin suture to the remaining stump, if present, or to the appropriate location along the orbital rim periosteum. Full-thickness margin repairs may be achieved by placing a single "buried vertical mattress" through the tarsus in line with the meibomian orifices (See Figure 1). This location is critical for wound strength and margin eversion. If the lid margin defect is not slightly everted at the time of repair, then notching is likely to develop. This technique uses a 5-0 to 7-0 polyglactin suture passed just like the traditional vertical ("far-far then near-near") mattress, except the suture passes begin and end within the deep tarsus, allowing the knot to be tied within the eyelid tissue rather than at the marginal surface. This avoids suture knot corneal abrasions and the need for later suture removal. Once the buried vertical mattress has been placed, it is temporarily tightened to ensure correct anatomic alignment and wound eversion. The stitch is then loosened to allow two to three interrupted 5-0 to 7-0 polyglactin sutures to be placed partial-thickness in the tarsus prior to tying the buried vertical mattress. A single simple interrupted infraciliary suture with the same suture material optimizes alignment of the lash line and anterior wound edge. The suture is cut close to the knot to avoid corneal contact, and the overlying skin can then be closed with 6-0 to 7-0 absorbable or permanent sutures. An eyelid repaired by this technique is shown in figures 2 and 3.3

7. Follow-up. Follow-up appointments should always be provided and specifically documented in the medical record. Permanent sutures are generally removed as follows: low tension eyelid wounds at three to five days, moderate tension eyelid wounds at five to seven days, high tension eyelid wounds at seven to eight days, and thicker skin wounds of the brow and face at five to 10 days. At all follow-up visits, meticulous chart documentation is critical, and supplemental photographic documentation is desirable.

The frequency of medicolegal entanglements in trauma cases is high for two reasons: 1) blame for the trauma is often ascribed to a third party, and 2) wounds and their subsequent repairs do not usually fall along traditional incision lines that are easy to camouflage.

Dr. Burroughs is chief of the ophthalmology service at Eglin AFB, Florida, and assistant professor of surgery for the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md. Contact him at jrburroughs@pol.net.

Drs. Patrinely and Soparkar are in private practice with Plastic Eye Surgery Associates, PLLC, in Houston and Pensacola, Fla.

1. Burroughs JR, Soparkar CNS, Patrinely JR, Williams PD, Holck DEE. Periocular Dog Bite Injuries and Responsible Care. Ophthalmic Plastic Reconstr Surg 2002;18:416-9.

2. Quickert MH, Dryden RM: Probes for intubation in lacrimal drainage. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1970;74:431-3.

3. Burroughs JR, Soparkar CNS, Patrinely JR. The Buried Vertical Mattress: A Simplified Technique for Eyelid Margin Repair. Ophthalmic Plastic Reconstr Surg. (In Print).