EVERY CATARACT SURGEON should have a game plan for when and how to perform an anterior vitrectomy following posterior capsule rupture. This article will review the goals, the indications, and the techniques. Understanding and mentally rehearsing these strategies will better prepare cataract surgeons to make correct decisions amidst the stress of an unexpected complication.

Vitreous Loss after PC Rupture

In many instances with a torn posterior capsule, it is possible to avoid rupturing the hyaloid face. The surgeon must avoid immediately withdrawing the phaco tip upon recognizing a posterior capsular defect. This abruptly unplugs the incision and allows the anterior chamber to collapse. The sudden posterior pressure gradient will rupture an intact hyaloid face, and vitreous will prolapse to the incision, expanding the capsular rent in the process.

This undesirable cascade of events can be avoided by filling the anterior chamber with viscoelastic prior to removing the phaco tip. As viscoelastic is injected through the side-port opening, the surgeon moves from foot pedal position one to zero. Once the chamber is filled, the posterior capsule cannot bulge forward as the incision is unplugged. If one resumes phacoemulsification or cortical cleanup, the same maneuver must be repeated whenever the instruments are removed.

Managing the Nucleus

Early recognition of posterior capsule rupture is often the key to avoiding a dropped nucleus. It is much easier to remove the nucleus while it remains anterior to the posterior capsule defect. Because subsequent instrument and fluidic forces approach the nucleus from above, they will eventually expand an unrecognized capsular defect enough to allow the nucleus to sink posteriorly.

One must often rely upon indirect clues to recognize a posterior capsular defect, because the iris and the nucleus obscure the zonular and posterior capsular anatomy. Sudden deepening of the chamber with momentary expansion of the pupil, the transitory appearance of a clear red reflex peripherally, and the inability to rotate a previously mobile nucleus can all indicate capsular or zonular rupture. More obvious and ominous signs would be excessive tipping or lateral mobility of the nucleus, or partial posterior descent of the nucleus.

If the remaining nucleus or fragments can be elevated into the anterior chamber with a dispersive viscoelastic, one can insert a trimmed Sheets' glide through the phaco incision to serve as an artificial posterior capsule, as described by Marc Michelson.1 The glide can keep lens material from dropping posteriorly and will shield the phaco tip from aspirating vitreous from below. The incision should be slightly widened to accommodate inserting the phaco tip above the glide. Maneuvers of the phaco tip should be minimized to avoid simultaneously moving the glide. This is one advantage of using bimanual microincision phaco instrumentation through separate 1.2-mm side ports in this situation if the surgeon is adept at this technique.

How far the nucleus initially descends will depend upon the vitreous anatomy. If the vitreous is very liquefied, the nucleus may rapidly sink to the retina precluding any response by the cataract surgeon. Alternatively, the nucleus may partially descend onto an intact hyaloid face. Such slight posterior displacement can be very subtle. Finally, if the hyaloid face is ruptured, the nucleus may tip or partially descend until it is suspended and supported by formed vitreous. In this situation, a rescue technique may be possible.

The worst tactic for recovering a partially descended nucleus is to try to chase and spear it with the phaco tip. Lacking the normal capsular barrier, the posteriorly directed irrigation flow will flush more vitreous forward, expanding the rent and propelling the nucleus away. Attempting to emulsify or aspirate the nucleus may ensnare vitreous into the large-diameter phaco tip. Applying suction and ultrasound following vitreous incarceration can produce a giant retinal tear.

The safer alternative is to elevate the nucleus into the pupillary plane or anterior chamber from below. There are, however, numerous obstacles to doing this. First, the pupil or capsulorhexis diameter may be quite small, which may have predisposed the eye to capsular rupture in the first place. A small pupil or capsulorhexis can impede elevation of a large nucleus and make it particularly difficult for a viscoelastic cannula to maneuver behind it. Prolapsed vitreous will further hinder such attempts to inject viscoelastic beneath the nucleus. The nucleus may suddenly sink if these maneuvers cause further vitreous loss and prolapse.

Charles Kelman popularized the posterior assisted levitation (PAL) technique in which a metal spatula, inserted through a pars plana sclerotomy, is used to levitate the nucleus into the anterior chamber from below. Compared to the phaco incision, a pars plana sclerotomy provides a much better instrument angle for getting behind the lens. Richard Packard, MD, and I subsequently published our results of using Viscoat (Alcon) and the Viscoat cannula to support and levitate the nucleus—the so-called Viscoat PAL technique.2

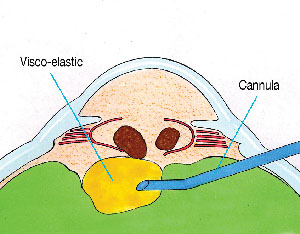

After opening the conjunctiva and applying light cautery, a disposable microvitreoretinal (MVR) blade (Alcon, Katena) is used to make a pars plana sclerotomy located 3.5-mm behind the limbus. An oblique quadrant should be selected. The Viscoat cannula is then advanced and aimed behind the nucleus under direct visualization. The first step is to inject a bolus of dispersive viscoelastic behind the nucleus to provide immediate supplemental support (See Figure 1). Periodic palpation of the globe confirms that overinflation has not occurred.

|

|

| Figure 1. Viscoat is injected via a pars plana sclerotomy behind the descending nuclear fragments to provide immediate supplemental support. |

If the nucleus is subluxated laterally, directing viscoelastic toward the region beneath it will often buoy the nucleus toward a more central position. This is preferable to blindly probing with a metal spatula. One should not attempt to float the nucleus into the anterior chamber using a massive infusion of viscoelastic alone. Unlike using liquid perfluorocarbon in a vitrectomized cavity, an excessive injection of viscoelastic may overinflate the globe and cause vitreous expulsion through the sclerotomy.

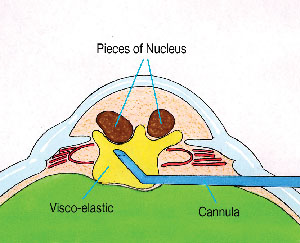

Instead, the cannula tip itself should be used to mechanically prop and levitate the nucleus into the anterior chamber (See Figure 2). Small aliquots of additional viscoelastic can be injected to help in the elevation and maneuvering of the nucleus. A small capsulorhexis or pupil will stretch to accommodate the levitation of a greater-diameter nucleus.

|

|

| Figure 2. The Viscoat cannula is used to carefully lift the fragments into the anterior chamber. |

Using dispersive viscoelastic to first support and reposition the nucleus prior to definitive manual levitation is the major advantage of the Viscoat PAL variation. Because there is no aspiration involved, these PAL maneuvers should minimize iatrogenic vitreous traction and reduce the chance of touching the retina with a metal spatula tip. Although Vitrax (AMO) is another acceptable dispersive agent, the smaller gauge cannula of the Viscoat syringe makes it the preferred choice for this technique.

Once a fragment descends into the mid or posterior vitreous cavity, it is dangerous to blindly fish for it with any instrument. One should abandon the dropped nucleus and concentrate on removing the residual epinucleus and cortex, while preserving as much capsular support as possible. A thorough anterior vitrectomy must be performed prior to inserting the IOL. Because the vitreoretinal surgeon will later use a three-port fragmatome and vitrectomy technique to remove any retained nucleus, it is preferable to insert an IOL through the cataract incision during the initial surgery, if possible.

The 'Viscoat Trap'

Any residual nucleus retrieved with the Viscoat PAL technique can be removed using either of two techniques—resuming phaco over a Sheets' glide or converting to a large incision manual extracapsular cataract extraction. At some point during this sequence, the phaco or irrigation-aspiration (I-A) tip may ensnare prolapsing vitreous. To avoid vitreous traction, the surgeon must stop to perform an anterior vitrectomy, before extraction of the remaining lens material can be resumed.

The most common practice is to place a separate self-retaining irrigating cannula though a limbal paracentesis and to insert the vitrectomy probe through the phaco incision. However, there are multiple drawbacks to this approach. First, the phaco incision is too large for the sleeveless vitrectomy instrument. This leaking incision provides poor chamber stability and allows both irrigation fluid and vitreous to prolapse externally alongside the vitrector shaft. Second, performing the vitrectomy in the anterior chamber will tend to draw more posteriorly located vitreous forward. Finally, as more and more vitreous exits the eye through either the cutting instrument or the incision, the residual lens material that it was supporting will sink down toward the retina. It bears repeating that once the posterior capsule is open, it is the vitreous that is preventing the remaining nucleus and epinucleus from descending.

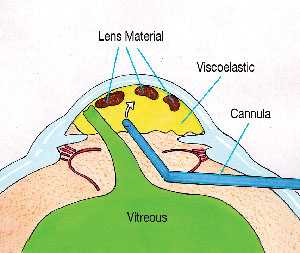

I have proposed a strategy, called the "Viscoat Trap," which, when combined with a pars plana anterior vitrectomy, can prevent this undesirable chain of events.3,4 The first step is to use a dispersive viscoelastic, such as Viscoat or Vitrax, to levitate any mobile lens fragments up toward the cornea. Next, completely fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic. Even though vitreous has already prolapsed forward, injecting viscoelastic should not exert traction on the retina. The dispersive viscoelastic can now support and trap the residual lens material in the anterior chamber as the vitreous is excised from below (See Figure 3).

|

|

| Figure 3. Following anterior vitreous prolapse, the residual lens fragments are elevated toward the cornea, where they are trapped by filling the anterior chamber with Viscoat. |

Bimanual Anterior Vitrectomy

As with the Viscoat PAL, the pars plana sclerotomy is made 3.5-mm posterior to the limbus. A disposable #19 MVR blade will create an adequately sized opening for most anterior vitrectomy cutters and should be advanced until it is visualized through the pupil. It is possible to perform this step under topical anesthesia alone.

A self-retaining irrigating cannula is placed through a limbal paracentesis and is angled toward the pupil. As described by Scott Burk, Md, PhD, staining prolapsed vitreous with a triamcinolone suspension to improve visibility is an option.7 The sleeveless vitrectomy shaft is inserted through the pars plana sclerotomy until the tip can be visualized in the retro-pupillary space. If it does not pass through the incision easily, it is important to slightly enlarge the opening rather than to force the entry.

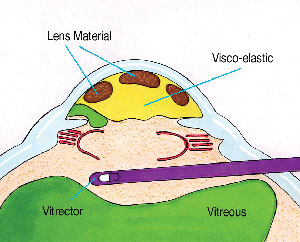

Using low flow and vacuum settings, and as high a cutting rate as possible to minimize vitreous traction, a thorough anterior vitrectomy is performed. One should focus posteriorly enough with the microscope to keep the tip under direct visualization at all times. One should attempt to keep the vitrectomy tip behind the pupil if possible. While any transpupillary bands of vitreous will still be severed, this will avoid removing the dispersive viscoelastic that fills the anterior chamber (See Figure 4).

|

|

| Figure 4. The sleeveless vitrectomy cutter is introduced via a pars plana sclerotomy and is kept behind the plane of the capsulorhexis and pupil. This severs the transpupillary bands, but keeps the vitrectomy separated from the partitioned anterior chamber. The self-retaining infusion cannula (not shown) is placed through a limbal stab incision. |

The pars plana sclerotomy is an underused option when performing an anterior vitrectomy. The principles of anterior vitrectomy technique are the same: one must not aspirate vitreous without cutting it; one should keep the vitrectomy tip under direct microscopic visualization; and one should not attempt to retrieve lens material that is in the posterior vitreous cavity.

The main advantage is that using a properly sized sclerotomy will decrease incisional leak and vitreous prolapse and should provide a better fluidic seal. Unlike with a limbal incision, the vitrector need not traverse the anterior chamber and disrupt the Viscoat partition, and it will not draw more vitreous forward into the anterior chamber. Performing the vitrectomy posterior to the pupil and the plane of the capsulorhexis also decreases the chance of inadvertently cutting either structure. If the capsulorhexis is preserved, a foldable posterior chamber IOL may still be implanted in the ciliary sulcus. The sclerotomy can be closed with an interrupted 8-0 Vicryl suture.

Following the retro-pupillary anterior vitrectomy, one can resume aspiration of the remaining cortex or epinucleus trapped in the Viscoat-filled anterior chamber. Bimanual I-A instrumentation is ideal for epinuclear and cortical extraction once the capsule or zonules have ruptured. One should attempt to work in "slow motion" by lowering the irrigation bottle and decreasing the aspiration flow and vacuum settings. If the aspirating ports become entangled with vitreous again, one can repeat the Viscoat Trap maneuver followed by additional pars plana anterior vitrectomy. Bimanual cortical I-A can then be resumed.

Cautious adherence to these principles may help surgeons to reduce the chance of dropping the nucleus following posterior capsular rupture. However, there is a potentially fine line dividing maneuvers that are reasonable and safe from those that are overly aggressive or dangerous. Cataract surgeons must be honest in assessing their own level of comfort and expertise. Timely surgical management of a dropped nucleus by a vitreoretinal surgeon at a later date is always preferable to overstepping this fine line.8

Dr. Chang is a clinical professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and is in private practice in Los Altos, Calif. He has no financial interest in any product or instrument mentioned in this article.

1. Michelson MA. Use of a Sheets' glide as a pseudoposterior capsule in phacoemulsification complicated by posterior capsule rupture. Eur J Implant Surg 1993;570-572.

2. Chang DF, Packard RB. Posterior assisted levitation for nucleus retrieval using Viscoat after posterior capsule rupture. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:1860-1865.

3. Chang DF. Managing residual lens material after posterior capsule rupture. Techniques in Ophthalmology 2003;1(4):201-206.

4. Chang DF. Strategies for managing posterior capsular rupture. In Phaco Chop: Mastering Techniques, Optimizing Technology, and Avoiding Complications. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Inc., 2004.

5. Burke S, Sugar J, Farber MD. Comparison of the effects of two viscoelastic agents, Healon and Viscoat, on postoperative intraocular pressure after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21:821-826.

6. Probst LE, Hakim OJ, Nichols BD. Phacoemulsification with aspirated or retained Viscoat. J Cataract Refract Surg 1994;20:145-149.

7. Burk SE, Da Mata AP, Snyder ME, et al. Visualizing vitreous using Kenalog suspension. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:645-651.

8. Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr., Smiddy WE, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of pars plana vitrectomy in patients with retained lens fragments. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1567-1572.

(See also: New PAL method may save difficult cataract cases. Ophthalmology Times 1994;19:51).