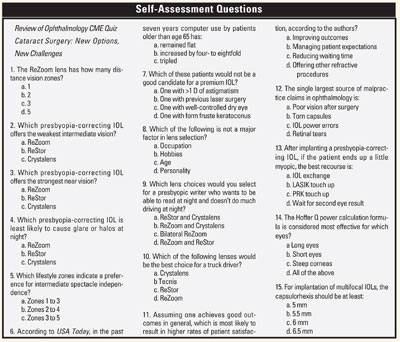

Release Date: July 2006

Expiration Date: July 31, 2007

Estimated Time to Complete the Activity: 1 hour

Target Audience: Ophthalmologists

Statement of Need: Cataract patients today face an array of options regarding their surgery thanks to the introduction of multifocal, accommodating and aspheric intraocular lenses. While these lenses may potentially reduce patients' postop reliance on eyeglasses or other visual correction, this is not guaranteed and every patient's outcome needs to be planned individually. Given the popularity of other refractive surgery procedures among the patient population and confusion regarding these options in that population, it's critical that cataract surgeons select patients appropriately for these new lenses, educate patients about realistic outcomes, and understand the appropriate steps to take when faced with outcomes that are less than ideal.

Learning Objectives:

1. Describe the clinical trial results of multifocal and aspheric intraocular lenses.

2. Describe the characteristics that improve the patient selection process when considering candidates for new IOL technologies.

3. Describe the available options to treat patients that have outcomes that fall short of preoperative surgical goals.

4. Describe techniques for setting realistic patient expectations for postoperative outcomes.

Faculty/Editorial Board: Y. Ralph Chu, MD, is an adjunct assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota. Audrey R. Talley-Rostov, MD, is a clinical instructor at the University of Washington.

Accreditation Statement: This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Review of Ophthalmology. PIM is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation: Postgraduate Institute for Medicine designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s). Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest: Postgraduate Institute for Medicine assesses conflict of interest with its instructors, planners, managers and other individuals who are in a position to control the content of CME activities. All relevant conflicts of interest that are identified are thoroughly vetted by PIM for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies utilized in this activity, and patient care recommendations. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality CME activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in health care and not a specific proprietary business interest of a commercial interest.

The faculty reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Dr. Chu receives consulting fees and has Contracted Research for Advanced Medical Optics. Dr. Talley-Rostov has no real or apparent conflict of interest to report.

Planners and managers: Jan Hixson, RN, MSN, Postgraduate Institute for Medicine: no conflicts of interest with any commercial interest related to this activity. Christopher Glenn, Review of Ophthalmology: no conflicts of interest with any commercial interest related to this activity.

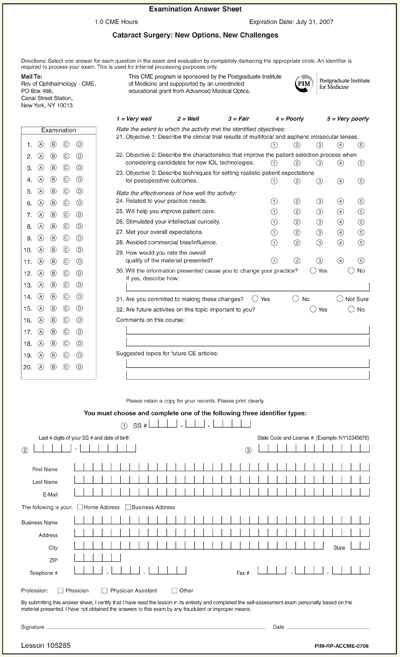

Method of Participation: There are no fees for participating and receiving CME credit for this activity. During the period July 2006 through July 31, 2007, participants must: 1) read the learning objectives and faculty disclosures; 2) study the educational activity; 3) complete the posttest by recording the best answer to each question in the answer key on the evaluation form; 4) complete the evaluation form; and 5) mail or fax the evaluation form with answer key.

A statement of credit will be issued only upon receipt of a completed activity evaluation form and a completed posttest with a score of 70 percent or better. Your statement of credit will be mailed to you within three weeks.

Media: monograph

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use: This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. PIM, Review of Ophthalmology and Advanced Medical Optics do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

| Matching the IOL to the Patient: One Size Does Not Fit All Y. Ralph Chu, MD |

With the availability of a host of new intraocular lens technologies, the modern age of cataract surgery demands a refractive-surgery mindset. In the old paradigm, surgeons typically had a standard favorite IOL that they implanted in most patients without much discussion about the IOL itself. Today, we can offer a much wider range of choices. These choices are tailored to the patient's lifestyle needs, so the patient plays an active role in deciding which lens to implant.

In addition to the traditional spherical monofocal IOL, we now also have several new monofocal options. There are three wavefront-designed IOLs with aspheric surfaces: the AMO Tecnis Z9000, Z9001 and Z9003 IOLs, the Alcon AcrySof SN60WF IQ, and the Bausch & Lomb SofPort AO. With each of these lenses, wavefront technology has been used to try to reduce some of the higher-order aberrations typically induced by cataract surgery. The Tecnis lens, which we use, is the only one with claims approved by the Food and Drug Administration for reduced spherical aberration and improved functional vision, as well as improved night driving safety.

There are also three presbyopia-correcting lenses. The AMO ReZoom lens is a refractive multifocal IOL that provides excellent distance and intermediate vision, and good near. Three of its five zones are distance-dominant, and the optic is designed to transmit 100 percent of visible light. The Alcon AcrySof ReStor lens has an apodized diffractive central zone for near and distance vision, surrounded by a large refractive ring dedicated to distance vision. In our experience, the ReStor has the strongest reading vision, but intermediate vision is very limited. Finally, the Crystalens (Eyeonics), is a modified plate-haptic lens with hinges that allow it to move to simulate accommodation. Unlike the multifocal IOLs, there are fewer reports of dysphotopsia symptoms, but the near vision achieved with this lens is weaker than that of the other two.

Customizing Lens Choice to Lifestyle

There are three steps in determining the best IOL selection for a given patient. The first is understanding the patient's lifestyle needs and visual demands. In our practice, we use a questionnaire based on one developed by Steven J. Dell, MD, in combination with a lifestyle history the technicians take during the preop workup.

The questionnaire helps us to assess and prioritize what is important to the patient. It asks, for example, whether the patient wants to be able to read without glasses and which types of activities he'd least mind wearing glasses for.

During the technician's interaction with the patient, we augment standard history questions with some additional questions about the patient's occupation (current or former); how often he uses a computer, reads or does handiwork; and whether she participates in sports or needs to drive at night. Those questions help us understand the range of vision these patients use in their daily lives and, therefore, which technologies would be most suitable for them.

The concept of dividing vision into five lifestyle zones, first described by William Maloney, MD , has been very helpful to us in guiding lens choice. The activities range from near tasks that would require a near-dominant lens or undercorrection in Zone 1 to distance tasks that would require pristine distance vision or perfect emmetropia in Zone 5. For patients, the real-world examples in these lifestyle zones are much more useful than asking them whether they want 20/20 or J1 vision.

I explain to patients that every lens has limitations. I can't offer them Zones 1, 3 and 5, for example. But knowing whether they would prefer to reduce their dependence on glasses for Zones 1 to 3, Zones 2 to 4, or Zones 3 to 5 is very helpful in lens selection, even when a presbyopic IOL is not under consideration. For patients scheduled for conventional IOLs, knowing more about daily activities and vision preferences can still help the surgeon set an appropriate refractive target.

For the presbyopic IOL patient who chooses Zones 1 to 3, who wants very good reading vision but is less concerned about intermediate vision and doesn't use the computer or drive at night, I might recommend the ReStor IOL because it offers the strongest near. It's very important that patients understand they will not have great intermediate vision with this lens, however. If a patient is concerned about night vision, he might be a good candidate for an accommodative IOL like the Crystalens.

|

| In a simulated night-driving study, the Tecnis lens provided an additional 45 feet of identification distance at 55 miles per hour. |

Many of my patients fall in the middle category, though. They want good "walking around" vision but don't mind wearing glasses for prolonged near tasks or night driving. The reason that so many patients have a preference for Zones 2 to 4 also has a lot to do with the rise in computer usage in the cataract patient population. According to a February 2006 USA Today study, the percentage of adults between 50 and 65 using a computer has doubled in the past seven years. Among patients older than 65, there has been a four- to eightfold increase in computer use. A refractive multifocal IOL such as the ReZoom lens provides very functional vision for glasses-free computer use and other intermediate-distance activities.

There was recently some very interesting data reported from Brazil, in which patients with a ReZoom lens in the dominant eye and a ReStor lens in the nondominant eye achieved greater spectacle independence without much sacrifice in their quality of vision.1 I am interested in this technique to overcome some of the limitations of each IOL, but surgeons should definitely get comfortable with implanting these lenses bilaterally first before venturing into mixing and matching.

Patient Personality and Ocular Health

It is essential that patients have realistic expectations of their postoperative vision. This is dependent partly on the preoperative education process, but is also related to the individual's personality.

Assessing personality type can be one of the most difficult aspects of this process for surgeons, especially if they have not had a refractive practice in the past. At least during a surgeon's early experience, it is best to avoid implanting presbyopic IOLs in patients who are overly perfectionist or have a negative, "glass-half-empty" personality. We ask patients to self-identify where they fall in a range from easygoing to perfectionist, but the surgeon also needs to make a gut assessment during the preoperative exam.

Of course, knowing the patient's visual needs and interests is only part of the equation. The next step in determining whether one of the newer IOLs is appropriate is the medical exam of the eye. To be eligible for implantation of an advanced aspheric lens or a presbyopic lens, the patient should have a healthy optical system. These IOLs demand minimal refractive error, including less than 1 D of astigmatism, for optimal outcome, so patients with form fruste keratoconus or other corneal pathology are not the best candidates. In my opinion, it is a mistake to implant one of these IOLs in an eye that would not be able to have corneal refractive surgery to fine-tune the result if necessary.

In our practice, we offer several intermediate choices between conventional spherical IOLs and presbyopic lens surgery, including the Tecnis aspheric monofocal lens, presbyoptics (a planned combination of spherical IOL implantation and conductive keratoplasty), and monovision.

We are currently involved in FDA clinical trials for the Tecnis Multifocal IOL (AMO) and the Synchrony dual-optic accommodating IOL (Visiogen). With new generations of multifocal, accommodative and wavefront IOLs becoming available, I think we'll be able to offer even better reading ability and better quality of vision, and someday even truly customize the IOL to an individual patient's eye. Practitioners who have already successfully accepted the new paradigm of refractive cataract surgery will find it easy to incorporate each of these new technologies as they become available.

The rapid expansion of intraocular lens options makes this an exciting time to be practicing lens surgery, but with the new paradigm come new challenges. Now, not only do clinicians need to educate patients about cataracts, but we also have to learn about their visual needs and desires and then educate them about the technologies that are available to meet those needs.

The patient education process starts long before the patient ever sees the surgeon. Every staff member, from the receptionist to the clinical staff, should be educated about the IOLs the practice offers. When a patient schedules an appointment, it is advisable to mail information about lens choices or direct the patient to a website to learn more about them before coming in for an exam. This material introduces the concept that, while there are new options, they also cost more than the traditional IOL.

In the office, posters, brochures, videos and other media can reinforce what the patient reads about in advance. The clinical staff is a critical component. As technicians are performing the preoperative diagnostic testing, they have an opportunity to introduce the new technologies verbally, in a more personal setting.

When the patient finally meets with me, my goal is to keep the discussion very clear, concise and clinically focused. I tell the patient which IOL(s) I would recommend for him, based on his exam and all the information the technicians gathered.

While I don't hesitate to tell patients what the costs are for different options, I prefer to let our patient coordinators, who see the patient after I make a lens recommendation, handle most of the financial discussion. The patient coordinator can walk the patient through the complexities of what insurance covers, flexible spending account options and financing. In my experience, the decision time for a patient to want a new technology IOL is very short. The conversation about how to pay for it can actually be the longest part of the process.

|

| A representation of Balanced View Optics in the near and distance zones of the ReZoom refractive multifocal lens IOL. |

A key message for patients—and for staff to understand—is that all the options are good. The traditional spherical lens has been used in millions of eyes and provides excellent visual outcomes. New IOL choices can improve patients' night vision or expand their range of vision so they are less dependent on glasses. Our job is to tailor a recommendation to patients' lifestyles and give them the information they need to make the best choice.

When a practice first begins to integrate new IOLs, all this education and discussion can feel like a lot of work. But the process soon becomes more streamlined as everyone understands their roles and becomes comfortable with the new lens technologies. Inevitably, some patients will need more chair time, and the schedule must be able to accommodate that.

Preoperative Workup

In our practice, the initial consultation is focused on determining the patient's lifestyle demands and conducting a general cataract surgery screening exam. Patients who opt for traditional IOLs are usually ready to schedule surgery after this initial visit. For the new technology packages we offer, there is another visit for additional diagnostic testing.

The fee the patient pays for an aspheric IOL or presbyopia IOL also includes advanced testing and procedures that are not covered by Medicare or insurance. For example, the fee for a multifocal lens implant includes wavefront and Pentacam imaging, advanced corneal analysis with the Orbscan, optical coherence tomography, specular microscopy and limbal relaxing incisions for astigmatism correction at the time of surgery, if needed. Compared to a standard IOL, aspheric or presbyopia-correcting IOLs require a more thorough diagnostic evaluation and full correction of astigmatism in order to realize the full benefits of the technology.

Billing Considerations

Many surgeons have provided some of these noncovered services with conventional lenses and just absorbed the costs because there was no other option.

Last year, however, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) opened the door to providing Medicare patients with presbyopia-correcting IOLs when it ruled that physicians may take into account the additional work and resources required for these IOLs and may bill the patient for services that exceed the physician charge for insertion of a conventional IOL.2 This is not the same as balance billing. Rather than just setting a price the market will bear and asking the patient to pay the balance of what is not covered by Medicare, the practice must charge a fair and reasonable price for the extra services and be able to document how that price was determined. Some practices use an actuarial approach with a single global fee for the procedure and all additional services, while others determine individual costs for each service (e.g., topography, LRIs).

Patients should sign a statement acknowledging that they will be charged for noncovered services. A "billing consent form" provides good protection for the surgeon, in addition to clarifying the patient's responsibilities for payment.

Incorporating patient shared billing, as some have called it, should be relatively easy for practices that have previously offered refractive surgery or other procedures for which they bill patients directly. Practices that are accustomed to billing only third-party payers may take advantage of the sample forms and templates now offered by most IOL manufacturers.

Getting Your Surgery Up to Snuff

It is incumbent upon the surgeon who wants to offer these new lens technologies to first maximize outcomes with monofocal IOLs by improving the precision of his biometry and IOL power calculations. I would certainly recommend personalizing an A-constant, and conducting intensive staff training to ensure that immersion A-scan or IOLMaster measurements are as accurate as possible.

The elimination of astigmatism is critical to success with these lenses, so surgeons should fine-tune their surgical technique to minimize induced astigmatism and learn how to perform LRIs or other techniques for correcting cylinder.

| Setting Realistic Patient Expectations Audrey R. Talley-Rostov, MD |

Patient-centered care has been described as health care that is responsive to patients' wants, needs and preferences.3 Generally speaking, health care in the United States has been moving toward this model of care for many years and in ophthalmology, the trend is even more pronounced.

As Dr. Chu has described, IOL selection today is very much driven by the patient's needs and preferences. Cataract surgeons are rapidly discovering what refractive surgeons have understood for some time: Patients' preoperative expectations play a critical role in their postoperative satisfaction levels.

We know that patient expectations of cataract surgery are already high in general. As patients increasingly pay out-of-pocket for premium IOLs, those expectations will almost certainly rise.

Very little has been published regarding ophthalmic patient expectations in the United States. Most of the patient expectations research to date has been in primary care; much of what exists in ophthalmology has been done in other countries, where significantly different health care systems and cultural norms make it unclear how applicable the research is to the United States.

In a recent review of the patient expectations literature, Aerlyn Dawn and Paul Lee, MD, JD, found that unmet expectations are common, that interventions to reduce expectations can be effective, and that patients place particularly high priority on communication and explanation of medical information.4 These are valuable lessons to keep in mind as we are educating patients about new technology IOLs.

First, we have to understand our patients' priorities. Research from Australia has shown that patients' actual priorities and what ophthalmologists believe their patients' priorities to be differ significantly.5

We all have older patients who like the way they look wearing glasses—an older woman, perhaps, who is a -3 or -4-D myope, but is happy wearing spectacles most of the time and being able to read without them. This is a patient for whom I would plan on postoperative myopia. By contrast, younger previous refractive surgery patients have very high expectations of being spectacle-independent after cataract surgery, even though they are among the most challenging in terms of accurate power calculation.

Patients who do not wear glasses before cataract surgery have a higher expectation of not wearing glasses afterwards.6 Listening to what patients really want and expect from surgery, then doing our best to ensure those expectations are realistic, is critical to success with all the new IOL options. As a clinician, I tend to be most interested in improving my surgical outcomes, but controlling patient expectations may be more effective in terms of maximizing patient satisfaction than actually improving their postoperative outcome.7

Managing Expectations

So how can we best manage expectations? The first way is to provide thorough, detailed information for patients about their medical condition (cataract), the phacoemulsification procedure, possible risks and complications, and the pros and cons of various lens options available.

An interesting British study compared two methods of educating cataract patients. One group of patients watched a video about the anatomy of a cataract, while the other group saw a video with much more detail about what to expect from cataract surgery. When they were surveyed, the group that saw the more comprehensive video expected more risk and discomfort. But after surgery, this group was more satisfied and felt less anxious than patients in the anatomy video group.8 This demonstrates that surgeons can best manage expectations by providing really good information preoperatively. The LASIK informed-consent process, which typically involves a long consent form and signed caveats, is a good model for cataract surgeons to use with presbyopia-correcting IOLs.

|

| This model, designed by William Maloney, MD, asks patients to choose three contiguous lifestyle zones based on which activities they would most like to do without glasses. |

Tamping down expectations for full spectacle independence with these lenses is very important. Even though many of my patients end up not wearing glasses at all, I want their expectation to be that they will still need glasses for some activities. My staff and I emphasize that our goal is to reduce their dependence on glasses and we ask them to identify the visual tasks for which glasses would be least onerous.

The majority of people in my practice like to have unaided distance and intermediate vision and don't mind glasses for prolonged reading. For those patients, the ReZoom lens is a great choice. It allows them to see the dashboard and drive, do their computer work and brief near activities like reading a menu in a restaurant, but for prolonged reading or reading very small print, they may still need to wear reading glasses.

People who expect perfection at all distances and in all situations should be a red flag. We have patients actually write in their own handwriting, "I understand I may need glasses for some activities after surgery, that my vision may not be absolutely perfect, and that I may want to have a secondary refractive procedure three to six months later to fine-tune my vision."

One of the reasons that patients so often expect full spectacle independence despite warnings to the contrary is that retention of information about undesirable consequences is known to be poor and to decline over time.9,10 In our practice, we reinforce our educational messages in a number of ways to improve retention. In addition to advance reading materials, patients use a software program in our office that goes over the procedure and expectations. They complete a checklist while watching an informed-consent video, and then my staff and I go over the information verbally with them as well, and give them a chance to ask questions. It's very important for the entire staff to communicate the same messages, because staff interactions with patients can significantly influence their expectations.

When the Patient Isn't Satisfied

Unmet expectations are a problem for a number of reasons. Dissatisfied patients take up more postoperative chair time, don't make positive referrals and may not be as compliant with postoperative regimens. Occasionally, they even sue for malpractice.

In an analysis of malpractice claims in ophthalmology over a 10-year period, cataract procedures represented one-third of all closed claims and one-quarter of total indemnity payments paid by the Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Co.11 The largest group of identifiable claims in the analysis (36, including 10 with indemnity payments) involved IOLs, and of these, wrong IOL power was cited in 17 cases, including seven with indemnity payments.

The largest sums in cataract-related malpractice cases are awarded to patients whose cases result in legal blindness or worse visual outcomes.12 But the OMIC data showed that a good or even excellent visual result was no guarantee against a malpractice suit.

Risk management experts in ophthalmology have long emphasized the importance of patient education and documentation of informed consent. In my experience, effective communication becomes even more important when something does go wrong or when a patient is dissatisfied. Sometimes just knowing the doctor isn't giving up on them is critical to patients. Surgeons need to spend appropriate amounts of time listening to their patients when they aren't fully satisfied, and identifying solutions to increase their satisfaction. This may include fine-tuning the visual result with an enhancement procedure and, if necessary, assistance with a temporary prescription to make them more functional while they're waiting.

Getting as close as possible to emmetropia is critical with presbyopia-correcting lenses, and surgeons must be prepared to deal with residual refractive error if emmetropia is not achieved.

The "fix," however, depends on the situation. If the refractive result is myopic or hyperopic by more than 1.5 to 2 D, the wrong power IOL has been implanted; I would elect to perform an IOL exchange within the first month. In my experience, such a gross error has only happened with previous refractive surgery patients, but one must be prepared for it in any case.

If the patient has significant (>0.75 D) cylinder prior to lens extraction, and has not had refractive surgery or other corneal abnormalities, I perform limbal relaxing incisions at the time of surgery. If, after lens implantation, the patient is hyperopic or has a little residual astigmatism, I generally opt to enhance the outcome with conductive keratoplasty, because it's a simple, minimally invasive procedure.

If the patient ends up myopic, the decision to enhance depends on whether it's the first or second operative eye, the amount of myopia and the happiness of the patient. In one recent case, I implanted a ReZoom multifocal IOL in the first eye of a young woman in her 30s. Despite meticulous biometry and the best possible IOL calculations, her postoperative refraction was -1.25 D, and she was miserable. The other eye still needed to be treated. I explained to the patient that we had several options to enhance the visual outcome, but that the first step would be to plan the treatment for the second eye based on the first eye's response. We did this and she ended up with a very nice range of vision with the multifocal lenses plus the unintended monovision. She was thrilled and no longer desired an enhancement.

In cases in which there is an unexpected refractive outcome, I always wait at least six weeks between the first and second eyes, to be sure that the refraction is truly stable. I then look for any possible errors in biometry and, if none are discovered, I calculate the power for the second IOL based on how the first eye responded. If the patient is still unhappy after both eyes have received lens implants, I would generally opt to perform a PRK enhancement for residual myopia with or without astigmatism.

Other than straightforward refractive error, there may be cases where the outcome is what the surgeon intended and expected, but the patient is dissatisfied with the quality or range of vision.

Again, it is wise to first counsel patience. It can take several months for some individuals to neuroadapt to their new visual system. All that may be needed is to listen to the patient's complaints, reassure him that his experience is normal, and that it will get better. If it doesn't get better, there are options.

The surgeon might choose to implant a different IOL in the second eye if the patient is not happy with the vision achieved with the first IOL. I implanted a Crystalens in the first eye of a female patient in her 50s who was averse to risking any night vision symptoms. She was warned explicitly that she would likely still need reading glasses afterwards. Despite a huge functional improvement in her distance vision, from 20/50 best corrected to 20/20 uncorrected, the patient was unhappy wearing +1.00 D reading glasses. In her second eye, I will probably opt for a ReStor lens for the strong near add.

Another patient who also had a Crystalens implant complained of halos and poor quality vision after surgery. Because the symptoms were unusual, I explanted the lens and put in a ReZoom lens, along with a CK enhancement. This was a previous refractive surgery patient whose high expectations, in retrospect, probably precluded total satisfaction with any presbyopic IOL.

In every case, one should strive to solve the problem by the least invasive means possible. It is certainly helpful for surgeons to have the full spectrum of refractive surgical services in their armamentarium. Otherwise, the options for correcting a small amount of refractive error are limited to the too-invasive IOL exchange or the undesirable course of referring the patient elsewhere for a laser or CK enhancement.

An Ounce of Prevention

The best strategy, of course, is to avoid residual refractive error in the first place. Meticulous preoperative measurements go a long way toward avoiding problems. Surgeons who want to implant presbyopia-correcting IOLs should first invest in advanced biometry and topography equipment, such as the IOL Master and Orbscan, because it is imperative to be as accurate as possible in patient selection and IOL power calculation. Surgeons should use the most accurate, most current power calculation formulas.

I prefer the Holladay power calculation formula generally, but for long (>24 mm) or short (<22 mm) eyes or for unusually steep (>46 D) or flat (<41 D) corneas, the Hoffer Q formula offers improved accuracy. The most challenging eyes are those with a history of refractive surgery. I always let these patients know that they have a higher chance of a power calculation error due to their previous surgery, and prepare them for the possibility of needing an IOL exchange.

Perfecting the surgical technique is very important to success with these lenses. The capsulorhexis should be perfectly round to avoid any decentration of the IOL. The size of the capsulorhexis depends on the selected IOL. For the Crystalens, the capsulorhexis must be no larger or smaller than 5 to 6 mm. For either of the multifocal IOLs, a slightly larger capsulorhexis of at least 6 mm is desirable. Patients should also be warned preoperatively that a capsule tear or problem with the capsulorhexis during surgery would preclude implantation of the presbyopia-correcting IOL and that we would instead implant a traditional IOL should that occur.

Personally, I also prefer bimanual small incision phacoemulsification. Although I have to enlarge one of the incisions to place the IOL, I find the fluidics of this approach achieve the best results in my hands.

1. Akaishi L, Fabri PP. PC IOLs mix and match technologies: Brazilian experience. Presentation, World Ophthalmology Congress, Sao Paolo, Brazil, Feb., 2006.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Ruling No. 05-01, May 3, 2005.

3. Gertais M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL (eds): Through the Patient's Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. San Francisc Josey-Bass, 1993.

4. Dawn AG, Lee PP. Patient expectations for medical and surgical care: A review of the literature and applications to ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 2004; 49:513-24.

5. Pager CK, McCluskey PJ. Surgeons' perceptions of their patients' priorities. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004; 30:591-7.

6. Hawker MJ, Madge SN, Baddeley PA, Perry SR. Refractive expectations of patients having cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31:1970-5.

7. Pager CK. Expectations and outcomes in cataract surgery: A prospective test of 2 models of satisfaction. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:1788-92.

8. Pager CK. Randomized controlled trial of preoperative information to improve satisfaction with cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:928.

9. Geerling G, Meyer C, Laqua H. Patient expectations and recollection of information about photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg 1997;23:1311-16.

10. Vallance JH, Ahmed M, Dhillon B. Cataract surgery and consent : Recall, anxiety, and attitude toward trainee surgeons preoperatively and postoperatively. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004;30:1479-85.

11. Brick DC. Risk management lessons from a review of 168 cataract surgery claims. Surv Ophthalmol 1999; 43:356-60.

12. Kraushar MF, Robb JH. Ophthalmic malpractice lawsuits with large monetary awards. Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114:339-40.