|

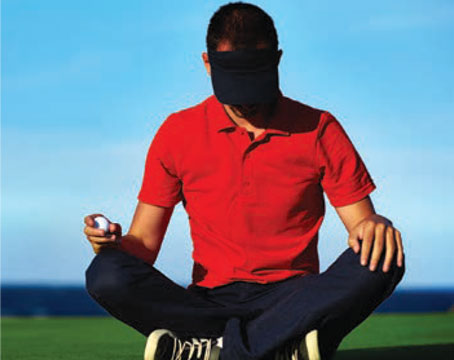

| Image courtesy of Getty Images. |

By the time you’re reading this column, the worst will be over. The days will be starting to get longer. Maybe not perceptibly, but that depends on where you are. Latitude is everything. OK, not really. The calendar is everything, but latitude is surprisingly important. But I get ahead of myself. I think most everyone can agree that a sunny day is better than a cloudy or dark one. We may not be sure why, but this seems to be the consensus. And there has been a fair bit of study on this phenomenon. As is often the case though, there are many confounding factors in assessing why we feel better, happier with more sunlight. Is it the number of hours of light? The intensity or wavelength? Are there other predisposing factors, such as underlying depression? And, if this is all true, what’s the biologic mechanism at play?

It seems that there are more than a few chemicals involved. More sunlight produces more serotonin, the happy molecule. Less serotonin=less happy. As you know, many antidepressants work through increasing serotonin. Autopsy studies and animal studies confirm higher levels of serotonin during the summer when there is more daylight.

Hours of sunlight also correlate with fluctuating levels of melatonin, in a cumulative fashion: higher at the end of the day, lower at the start. This may not be directly responsible for feeling good but, trust me, higher levels of endogenous melatonin providing a good night’s sleep will make anyone feel better the next day. I doubt anyone here will be offended, but this may be why night-shift nurses are a tad grouchy, as I’ve recently been reminded. Sleeping all day and working nights is not what our physiology was built for.

Many people have some underlying tendency toward melancholy or even depression. And for a subset of those, seasonal changes in affect are specifically correlated to hours of sunlight. Colloquially known as Seasonal Affective Disorder, I would submit that to some degree or another, a large part of the population manifests SAD at this time of year. The long-standing feud over daylight savings time is in many ways an effort to minimize SAD, since very few want to leave work at the end of the day in darkness. It’s pretty depressing. Even if it isn’t mid-December, it is possible to be depressed any time of year when for extended periods the sun isn’t out. Rain and clouds for a few days will definitely have an effect on me no matter what time of year, and the typically overcast weather in Philadelphia during the winter makes it all the worse.

And now, as promised, we’ll return to latitude. We know that during the winter in the northern hemisphere higher latitudes have shorter days and at some point the sun doesn’t even rise at all depending on where you are. Somehow though, I’ve always thought of that as some bizarre extreme that involves polar bears, that you wouldn’t really experience that in the United States.

Aside from perhaps northern Alaska that’s true, but you don’t have to trek thousands of miles to notice the relationship of latitude and daylight. As part of my transition to retirement, I now have a residence in Florida as well as Philadelphia. And during the winter, I travel between the two regularly. It’s not that far a trip, about 1,000 miles as the crow flies. I quickly noticed an interesting phenomenon, however. In the evening at this time of year, it’s totally dark up north by 6 p.m., but in Florida the sun has over another hour left. And let me tell you, living that difference is pretty magical. Latitude and better weather certainly earn Florida its nickname as the Sunshine State. Unfortunately, especially this time of year, it’s not always sunny in Philadelphia.

Dr. Blecher is an attending surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital.