One of the many pitfalls to deal with when a patient has two co-existing diseases is the confounding possibility that the treatment for one will interfere with—or even worsen—the other. Such is the case with uveitic glaucoma patients. In these cases, one of the mainstays of uveitis treatment—steroids—can exacerbate the glaucoma while, at the same time, the inflammation can make successful glaucoma surgery more difficult to achieve. In this article, I’ll share my approach to managing these challenging cases.

Etiology

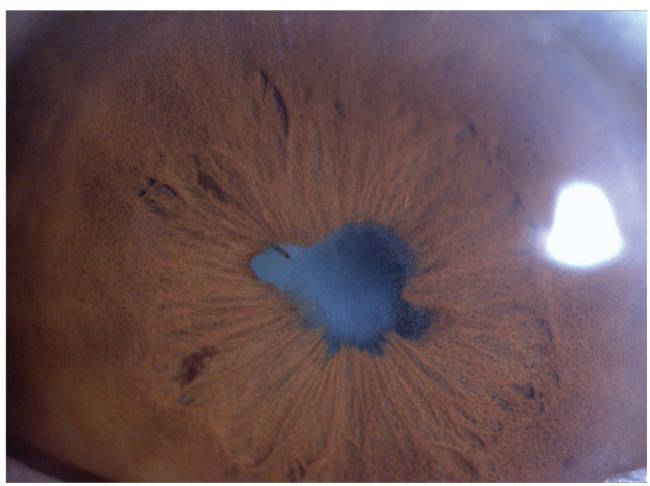

Uveitic glaucoma occurs in about 20 percent of patients with uveitis. There are multiple reasons why it may occur: inflammatory cells obstructing the trabecular meshwork; peripheral anterior synechiae; pupillary block; trabeculitis; and as a response to the steroids being used to treat the uveitis. There can also be instances of inflammation of the trabecular meshwork that results in elevated intraocular pressure.

Workup and Management

If a patient presents with a history of uveitis and elevated IOP, there are several key aspects of diagnosis and management to keep in mind.

• Look at the medication regimen. This is one of the first things the clinician will want to do. Is he currently using steroids? If so, how often? Altering the steroid regimen is one of the simplest, most straightforward actions you can take in these cases. In addition to measuring the patient’s visual acuity and IOP, be sure to perform gonioscopy to check for anterior synechiae, and make sure there are no posterior synechiae that might cause pupillary block.

You may want to change the steroid regimen. Some patients arrive in your office from the uveitis specialist and they have quiet eyes due to a strong steroid regimen. In these cases, it might be beneficial to decrease the frequency of the steroids to see if they’re steroid responders. In some cases, however, you may not be able to do this. If you do find—or suspect—posterior synechiae, there’s a higher chance, unfortunately, that manipulating the frequency of the steroids might not do anything for the patient, since the trabecular meshwork is closed by the synechiae.

• Consider an iridotomy. If you think pupillary block is the cause, a laser iridotomy can open a passage between the posterior and anterior chambers.

• Use your imaging and diagnostic tools. You may find that the patient has elevated IOP from steroid use but no evidence of glaucoma, or that the steroids have increased the pressure and there’s also evidence of nerve damage. Use your diagnostic tools, such as visual field exams and optical coherence tomography of the optic nerve, to get a baseline for the patient so you can follow him over time. I will sometimes also perform anterior segment OCT in certain individuals in order to document whether there’s synechiae or not. This last step isn’t always necessary, but it can be informative in some patients.

Sometimes, nerve fiber layer measurements appear normal in a patient with glaucoma; that’s why longitudinal information is very important. The nerve fiber layer should correlate with your clinical diagnosis first. Then, follow the patient over time to get a better idea of his status. It’s important that your imaging and functional testing agree with your exam. For instance, if I see a cup that appears large and potentially glaucomatous, but the OCT doesn’t confirm that, I’m suspicious, but I’ll need longitudinal data to help with the diagnosis and management.

|

| Working with a uveitis specialist is key, as you may need to alter the uveitis therapy. |

• Communicate with the patient’s uveitis specialist/rheumatologist. It’s important to work hand-in-hand with this person, because you may need to take some uveitis patients off of steroids or, depending on the severity of the uveitis and its cause, switch to other immunosuppressive modalities to control the inflammation.

When I’m working with the uveitis specialist, I follow his recommendations. I do my best to control the inflammation while controlling the pressure, and won’t tolerate any cells in the anterior chamber, if possible.

• Manage the inflammation. Initially, if the eye is very inflamed, the patient is prescribed Pred Forte or Durezol for use every one to two hours while awake, in addition to Cyclogyl or homatropine, depending on the severity. For the latter two drugs, I prefer alternating between twice a day and once a day, which doesn’t keep the pupil dilated or constricted in the presence of a lot of inflammation. I like to have the pupil moving on and off in order to decrease the chance of synechiae.

Depending on the severity of the inflammation, I eventually begin tapering the steroid. Long ago, I learned that a slow taper is important; the faster you taper, the higher the chance of developing rebound inflammation that can be hard to control.

If the eye is very quiet, or is close to being quiet, but the IOP is trending upward, I’ll alternate the steroid with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drop to help with the inflammation. This allows me to decrease the steroid regimen; instead of using it three times a day, the patient can use it only twice, or even once. I then can also slowly taper it. If the eye is then quiet for a while, I take away the steroid and keep the patient on the NSAID for a longer period. This approach has also worked in patients who were steroid responders but whose inflammation wasn’t severe. (If it’s bad, though, this approach won’t work.)

If the inflammation is severe and the patient is a steroid responder, it’s important to assess the pressure. If it’s a little on the high side, and I have time to work with a uveitis specialist to help switch the patient to another modality for controlling the inflammation, like methotrexate or CellCept, I will. The issue is that these immunomodulators usually have a loading time of a few months before they’re fully functional in the patient. I’ll work with the uveitis specialist to slowly take the patient off of the steroids as the immunosuppressive therapy is introduced.

Sometimes I don’t have time for this approach, because the pressure is very high and there’s a risk of damage to the optic nerve. In such cases, I take the patient to the operating room to insert a glaucoma implant, hitting the eye hard with preop prednisone drops and p.o. prednisone if needed, intraoperative IV prednisone and more drops postoperatively to decrease the inflammation with the option to use p.o. prednisone.

In some of these cases, the patient can develop complications such as psychosis from the oral steroids, and I’ll need to work with the immunologist or uveitis specialist to start immunotherapy and get the patient off of the oral corticosteroids.

If the etiology of the inflammation is viral (i.e., herpetic), you’re likely to use a steroid and begin treatment—or maintain treatment—with acyclovir, in a way similar to conventional herpes therapy. If the herpetic patient’s pressure remains high regardless of treatment and the inflammation is chronic, then you’ll most likely need a glaucoma implant to control the intraocular pressure.

• Manage the glaucoma. Naturally, if the pressure is high in these patients, you should start treating with glaucoma drugs immediately. Most physicians will use a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, beta blocker or alpha agonist. On rare occasions, we’ll use a prostaglandin as a temporary solution for a high pressure, but we usually avoid prostaglandins in these patients because they can induce a low-grade inflammation. (I haven’t used Rhopressa in uveitic patients yet but, if I needed something else, I’d probably try it.)

In terms of dosages, most of the time I use a CAI or alpha agonist twice a day, though I will occasionally prescribe them three times daily. In some cases I’ll use Diamox pills (250 mg, b.i.d.). I’ll rarely prescribe Diamox 500 mg, because some patients find it hard to tolerate, depending on their body weight and overall physical condition. If the patients fail medical management, or can’t tolerate it, we’ll move on to surgery.

Surgery

In some cases, modifying the drug regimen won’t be enough, and the patient will require surgery.

In cases that need surgery for their glaucoma, I prefer to have the eye as quiet as possible. In some cases, however, I don’t have the luxury of time and have to perform immediate surgery. Depending on the severity of the disease, I start the patient on p.o. steroid preoperatively, administer IV steroids during the procedure and then prescribe a Medrol dose pack p.o. for a week postoperatively. If the preop inflammation is severe, and I had to operate in the setting of this severe inflammation, I’ll keep the patient on the p.o. prednisone for longer than a week, and taper it slowly. In some less-severe cases, though, I’ll forgo the preoperative steroid regimen and just administer the intraoperative IV steroids and the p.o. postoperative steroids. The duration of the steroid regimen is based on the the degree of inflammation.

The other consideration is which surgery to choose for these patients. If there’s inflammation in the eye, a trabeculectomy will most likely fail, so your first line of surgical treatment will be a tube implant.1 One study showed that a trabeculectomy can work in some cases, but only if you have zero tolerance for cell and flare in the anterior chamber in the uveitic patient. This is difficult to achieve, however, especially if you’ve just operated; for the trabeculectomy to work, the eye has to be very stable and without inflammation for a long time.

Since glaucoma implants are usually the procedure of choice in these patients, I prefer using an Ahmed valve because of the risk of hypotony early on when there’s inflammation present. There’s also a risk of later hypotony as well. I’ve operated on a few patients in whom I first did a glaucoma tube and then a trabeculectomy years later after the inflammation resolved, and there was no evidence of recurrence for a few years.

Some surgeons will do what is known as an “orphan” trabeculectomy in addition to a non-valved Baerveldt glaucoma implant. It’s called “orphan” because the surgeon performs the trabeculectomy with the knowledge that it will most likely fail after a few weeks, but by that point the tube will have started working. I don’t like this approach, though; I feel that there is distinct “real estate” in the eye and, for the glaucoma patient, every millimeter is important, since you might need to use it later for a future glaucoma procedure. Using up this real estate in order to perform a procedure that I expect will fail doesn’t seem like a good use of it.

In some cases of mild uveitis and glaucoma I’ve had success using the Trabectome instead of a tube. Other, newer minimally-invasive glaucoma surgeries might be effective in uveitic glaucoma too, but I’ve only had experience with the Trabectome in such patients.

I’ve also worked with a uveitis specialist in implanting the Retisert sustained-release steroid implant. This is implanted during pars plana vitrectomy, cataract extraction and glaucoma implantation. The Retisert can work for two to three years in patients who aren’t compliant with drops. One of the limitations, though is the price. According to the drugs.com pricing guide, a single Retisert costs $19,871.2 Other sustained-release anti-inflammatory options are Ozurdex (Allergan) and Yutiq (EyePoint).

A lot of these patients will also need cataract surgery because they’ve been on chronic steroids for a while. In many of these cases, I’ll do the glaucoma surgery and the cataract procedure simultaneously. If there isn’t evidence of cataract, though, I might do the glaucoma procedure alone and come back later if a cataract develops. The one consideration is that you may have to adjust your wound based on the position of the tube.

The cataract procedure itself is a little more complex, since there may be synechiae you have to break or membranes you have to cut. You might need to employ a pupil-expansion ring or iris hooks. (Glaucoma specialists are used to these complex cases.) My inflammation control regimen after cataract surgery in these patients is similar to that for glaucoma surgery: oral prednisone both pre- and postop, Pred Forte or Durezol every one or two hours postop, and cyclopentolate.

Managing the uveitic glaucoma patient can be challenging, and requires a team approach. The uveitis specialist has tools to help control the inflammation, which can help you better manage the glaucoma. Working together, you can help guarantee better results for the patient. REVIEW

Dr. Al-Aswad is an associate professor of ophthalmology at Columbia University Medical Center’s Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute. She also serves as the Institute’s glaucoma fellowship director and the director of the tele-ophthalmology initiative. She has no financial interest in any products mentioned.

1. Da Mata A, Burk SE, Netland PA, Baltatzis S, Christen W, Foster CS. Management of uveitic glaucoma with Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation. Ophthalmology 1999;106:11:2168-72.

2.Drugs.com Retisert pricing. https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/retisert. Accessed 2 April 2019.