The Paradox

Excessive tearing can be paradoxical because patients come in complaining of tearing; but they really have a dry eye, says Stephen C. Pflugfelder, MD, professor and director of the ocular surface center at Baylor, department of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dry eye disease is an abnormality of tear film resulting in changes in the ocular surface. These changes usually are seen on ocular examination with the use of fluorescein and supravital staining techniques. The two main types of dry eye disease are aqueous deficiency and evaporative loss.1

Dry eye is one of the most frequent pathological conditions in ophthalmology, with a prevalence of 14 to 33 percent worldwide.2-5 Symptoms related to dry eye are among the leading causes of patient visits to ophthalmologists and optometrists in the United States.6 However, only recently have treatment recommendations been developed to uniformly treat patients with the syndrome.7 (See Guidelines for Treatment below.)

"Doctors should maintain a high suspicion for dry eye or some ocular surface problem when a patient has tearing," says Dr. Pflugfelder.

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, co-chief of cornea service at Wills Eye in Philadelphia, concurs. Many times patients with tearing thought to be related to dry eye receive treatment with tears or medications to increase their tear production, like Restasis (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion, Allergan) and their symptoms get better, he says.

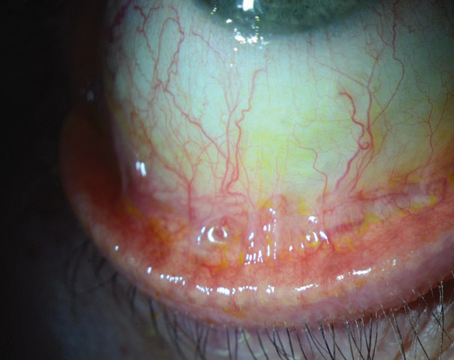

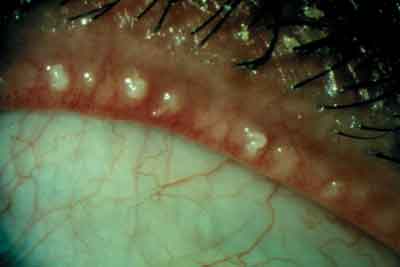

Slit lamp photos of significant superficial punctate keratopathy (SPK), which can be from dry eyes and can cause secondary tearing.

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD

However, this paradox often confuses patients, and ophthalmologists have to take the time to explain how dry eye works. "When I tell patients that I am going to give them a drop to produce more tears, they think I have not been listening to them describe their symptoms. You really have to explain to patients that they are getting excessive tears as a response to dryness," says Dr. Rapuano.

If tearing is related to dry eye it is often intermittent tearing. "The way I explain it to patients is by telling them they are not producing enough tears, the eyes dry out, and they get little microscopic scratches on the surface, or dry spots, from the dryness. Then the body senses those microscopic scratches and this causes a reflex or excessive tearing," he explains.

Evaluation

Once a patient presents with the symptoms of excessive tearing, an evaluation is done based on history and an examination is also done to determine whether dry eye is the cause. Leslie M. Sims, MSPH, MD, an ophthalmologist in practice in New York City, routinely evaluates tearing patients in her practice.

"First, I interview them to determine when the tearing occurs: Is it only in certain places, at certain times of the day or while performing certain tasks? Next, I look at the patient demographic. For example, menopausal women are more prone to dry eye," she says.

Dr. Rapuano notes that the patient history provides clues. "For dry eye, the eye is usually intermittent—dry part of time and it is really wet part of the time—as opposed to the people who have lacrimal obstructions. They often have tearing all the time—all day, every day; every five minutes they need a tissue," he says.

Eric D. Donnenfeld, MD, in practice in Rockville Centre, N.Y., agrees that a comprehensive history is an important first step in diagnosis. "For the most part, when I evaluate someone who has a history of tearing, I want to know if it is in one eye or both eyes. With dry eye, it is almost always a bilateral problem but not in every case. I also want to know if patient has burning and irritation with tearing or more itching (itching being more suggestive of ocular allergy). If the tearing is worse in the morning, it is most likely going to be meibomianitis or blepharitis with abnormal lids oils. If it is worse at the end of the day, that's more suggestive of aqueous deficiency or dry eye," he says.

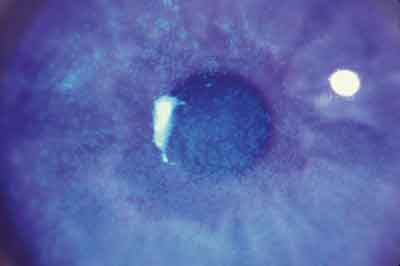

Figure 3. Staining the patient's cornea is a key way of finding out what is causing the excessive tearing. This slide shows lissamine green staining of the cornea in a patient with exposure keratitis.

Eric Donnenfeld, MD

Dr. Donnenfeld also asks patients about risk factors for dry eye, including autoimmune disease, Sjögren's syndrome, and allergic diseases that may be causing tearing, such as asthma, eczema, or atopic dermatitis.

It is also important to ask patients about ocular trauma, radiation treatment, and the presence of diseases such as thyroid disease, and medications the patients may be taking such as hormone replacement therapy, blood pressure medicines or histamines, that could cause dry-eye problems, says Jonathan M. Davidorf, MD, medical director at Davidorf Eye Group, in West Hills, Calif. "Any of these historical factors could be contributory toward dry eyes or blepharitis," he says, adding that patients may need to follow up with their primary doctor to adjust their medication regimen.

Examination

A careful examination can also show signs of dry eye syndrome (See Figures 1 and 2). "When I evaluate a patient with tearing I ask if they have a foreign body sensation that goes along with it or if they have had previous ocular surgery that can explain the tearing," Dr. Donnenfeld says, adding that he checks for exposure keratitis and lid problems that can produce tearing due to poor lid apposition.

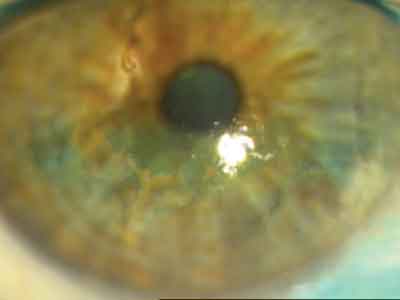

"I will check the lid margin for blepharitis and meibomianitis, and also look at tear film itself. I examine the quality of the tear film; whether there is debris or there is significant tear quantity or low quantity; I want to check the lacrimal apparatus to make sure that the puntctum is open and in good position, making sure that there is never a sign of dacryocystitis," he says.

Dr. Sims takes a similar approach. "Because dry eye patients tend to complain of a foreign body sensation or increased mucus production, examination of the ocular surface at the slit lamp is important. I want to observe the quality of the tear film and the tear meniscus, or the tear lake," she says.

Testing

Dr. Donnenfeld points out that staining the patient's cornea and observing the resulting pattern often provides the most important physical finding (See Figures 3 and 4).

"I stain the patients with a supravital stain, such as lissamine green or rose bengal," he says. "If I see the classic interpalpebral staining of dry eye with a V-shape distribution in the interpalpebral fissure with mild fluorescein staining in the central cornea, this almost always gives me a diagnosis of dry eye. If the staining is more inferior, it may be because of a toxic keratitis, blepharitis or something in the tear film that is causing the problem. If it is superior staining, it may be SLK. Very commonly, patients who have mucus fishing syndrome will mechanically rub their eyes and cause irregular staining patterns."

Dr. Davidorf typically relies on a fluorescein dye study to assess the pattern of the staining of both the conjunctiva and the cornea. "We look not just for superficial punctate staining, but for negative staining as well, which may be indicative of a mild anterior basement membrane dystrophy," he says.

The Schirmer test, which measures tear secretion, can also help narrow down the dry eye diagnosis. "In the Schirmer test, the amount of wetting on filter paper placed in the cul-de-sac of the lower eyelid is recorded," Dr. Sims points out. "The normal amount of wetting is 15 mm at five minutes. Any amount less than that could be indicative of a dry eye."

Dr. Pflugfelder adds, "Although the Schirmer test is not extremely sensitive or specific, in some cases it can be helpful. For example, if the patient was complaining of tearing and the test reading was very low, then it would point to a dry eye. If it were very high, it might indicate that there is excessive reflex tearing or there is some obstruction of the drainage."

Dr. Rapuano notes that ophthalmologists can also irrigate the lacrimal drainage system to see if there is a blockage. "This might tell you that it is not dry eye, but something else," he says.

Treatment

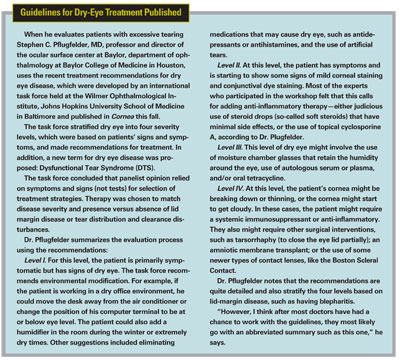

Treatment options vary with the extent of the signs and symptoms of the patient. Guidelines for dry eye treatment developed by a task force held at the Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore, were published in the September issue of Cornea (See Guidelines for Treatment above).

Figure 4. Meibomian gland inspissations.

Eric Donnenfeld, MD

"Overall, treatments range from artificial tears (with or without preservatives) to punctal occlusion with punctal plugs (which slow the drainage of the tears) to Restasis, which has been shown to improve the quality and quantity of tears. In my practice, Restasis has been very effective with my dry eye patients," Dr. Sims says.

Once the diagnosis of aqueous deficiency dry eye is made, the patient can be treated for it. "If it is mild, I will start with tears. If it is not responsive to tears, I will move on very quickly to immunotherapy with cyclosporine and topical corticosteroids. I will add oral nutritional supplements, such as TheraTears Nutrition (Advanced Vision Research, Inc.)," he says, adding that fish oils and flax seed oils may also help.

If lid disease is present hot compresses and lid hygiene can be effective. "If I think the eyelids are playing a significant role in the problem, I sometimes will add oral doxycycline," he says.

In addition, Dr. Donnenfeld checks to make sure the lids are functioning normally. "I find that very commonly patients with tearing will have some type of lid abnormality and correcting the lid abnormality really goes a long way to helping the patient."

1. Perry HD, Donnenfeld ED. Dry eye diagnosis and management in 2004. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004;15:299-304.

2. Schein OD, Munoz B, Tielsch JM, Bandeen-Roche K, West S. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;124:723-8.

3. Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:318-326.

4. Lin PY, Tsai SY, Cheng CY, Liu JH, Chou P, Hsu WM. Prevalence of dry eye among an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: The Shihpai Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1096-101.

5. Brewitt H, Sistani F. Dry eye disease: The scale of the problem. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;45:S199-S202.

6.Lemp MA. Epidemiology and classification of dry eye. Adv Exp Med Biol 1998;438:791-803.

7. Ashley Behrens, M.D. et al. Dysfunctional Tear Syndrome: A Delphi Approach to Treatment Recommendations, September 2006 Cornea. Publication pending.