Cornea transplants have evolved significantly in the past two decades—from full penetrating keratoplasty becoming less common, to the introduction of Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and, ultimately, the development of Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty, which is becoming increasingly accepted for both normal and complex eyes. These improvements have appealing benefits, including decreased risk of graft rejection and faster recovery time, and offer the opportunity for further efficiency if the case also involves a cataract.

Recognized as the “triple procedure,” it classically consisted of a full-thickness, corneal transplant/PK combined with cataract surgery and IOL implantation. This was the standard for 50-plus years until Gerrit Melles, MD, PhD, pioneered several new EK techniques, including DSEK and DMEK, which were then championed in the United States by Mark A. Terry, MD, the director of corneal services at Devers Eye Institute in Portland, Oregon.

These were welcome changes for the cornea community. “Although full-thickness corneal transplants were our only option, we always wondered why we couldn’t just replace the endothelial layer and Descemet’s membrane, which were the culprits of disease,” says Sadeer Hannush, MD, a cornea specialist at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. “Yet, all these years we were doing PK with all the risks that came with it, including open-sky surgery and 360- degree sutures.”

As cornea specialists became more familiar with the fundamentals of DSAEK and DMEK in the early 2000s, Dr. Terry coined the term “the new triple procedure” to reflect the updates in techniques and help standardize the approach.1 Since then, DMEK has become the preferred technique in the new triple procedure, according to Dr. Terry, although DSAEK and DLEK have their applications in certain scenarios.

In this article we’ll take a look at the lessons learned and discoveries made by surgeons who routinely perform triple procedures, including IOL selection, staging, intraoperative medications and techniques.

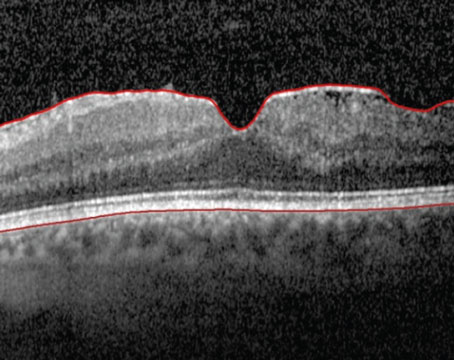

|

|

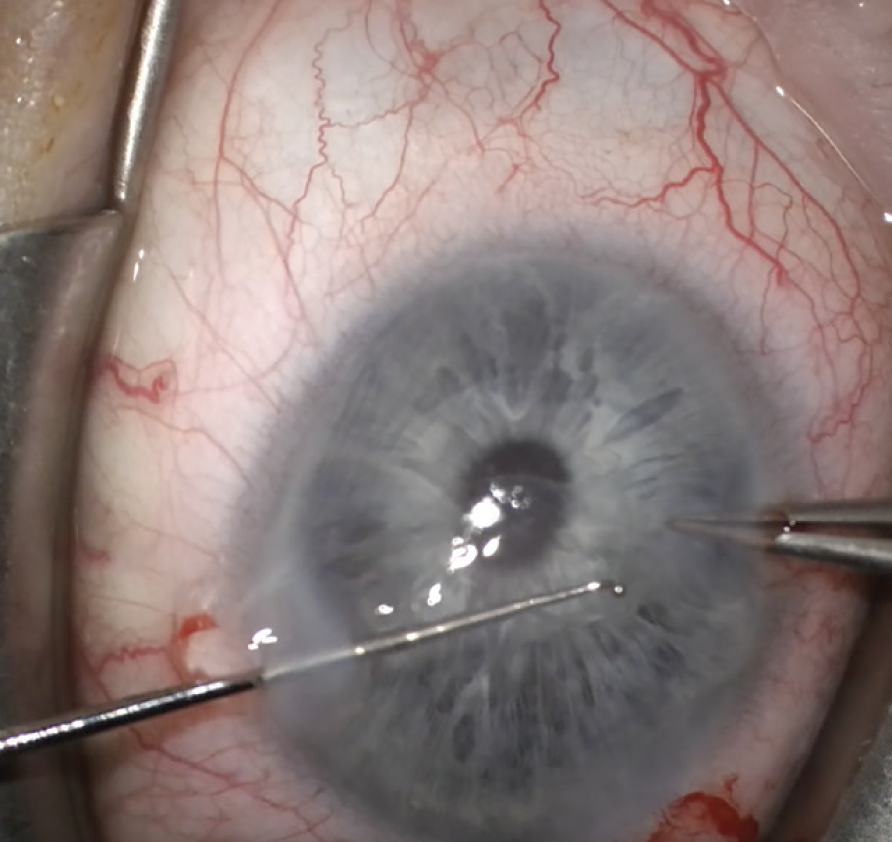

In a triple procedure, surgeons must balance pupil dilation with pupil constriction and approach it differently than traditional cataract surgery. Cornea specialists recommend phenylephrine for dilation followed by Miochol or Miostat for constriction, and say it’s better to avoid cycloplegics and NSAIDs because they’ll inhibit the constriction mechanisms. (Courtesy Sadeer Hannush, MD). |

Major Considerations for the Triple Procedure

One of the most challenging aspects of cataract surgery combined with a corneal procedure is predicting the refractive shift. Additional thought should be given to IOL selection, experts say.

“For the IOL, you have to choose what focusing power it will have, and one problem with the new triple procedure is that we don’t always know exactly what the focusing power of the cornea will be after the EK,” says Dr. Terry. “We know that it won’t be as far off as it was in the old, full-thickness transplant days, but in the new triple procedure we know that there’s a hyperopic shift with EK. That hyperopic shift is more predictable with DMEK than it is with DSAEK. DSAEK tends to almost always have a hyperopic shift such that, if you just put in what you would put in for cataract surgery for the IOL power, you would end up with a hyperopic result.”

Dr. Terry says, in order to prevent a hyperopic refractive result in the new triple procedure, surgeons should choose a lens that would normally result in a mildly minus result. “When you do your IOL calculations for the DMEK triple procedure you want to aim for about a -0.5 to -1 D for your refractive result so that you don’t end up with a hyperopic refraction postoperatively,” he continues. “You’re compensating for the expected hyperopic shifts of the DMEK surgery by choosing a lens that, if it was a standalone cataract surgery, would give you a -0.5 or -1 D myopic result, but in reality you’ll end up closer to emmetropia if you shoot for a myopic result.”

To further complicate things, this has to be tempered with the understanding that approximately 40 percent of cases will have a slight myopic shift instead of a hyperopic shift. “That myopic shift induced by DMEK surgery is usually very low-level, less than 0.5 D, but it’s there and you can get hyperopic shifts that are more than 1 D,” Dr. Terry says. “So there’s still a fuzziness to the calculations that you’ll do because of biologic variability on the refractive result of a DMEK surgery.”

|

| When stripping host Descemet’s, cornea specialists tend to strip an area larger than they’re transplanting. Here, Kourtney Houser, MD, uses a Fogla stripper, which has a ball on the tip to help keep it from penetrating too deep into the stroma. (Courtesy Kourtney Houser, MD) |

Another consideration is whether or not a triple procedure is the best plan. If there’s corneal edema affecting the epithelium, determine how severe it is before proceeding. Dr. Terry says, “If the corneal edema is very severe where it causes actual microcystic epithelial edema, it causes the epithelial surface of the cornea to be warped because of the swelling. In cases with an irregular epithelium, then you shouldn’t be doing a triple procedure. And this is something to emphasize—if the swelling is so bad that it’s distorting the surface of your cornea preoperatively, then you can’t get adequate keratometry or topography readings because the surface is so irregular. In this case, the strategy should change and you shouldn’t do a triple procedure.”

Instead, Dr. Terry recommends performing DMEK surgery first and waiting at least two to three months before the cataract surgery. “The rationale behind the strategy of sequential surgery is that you want the smoothest corneal surface possible to determine what your IOL power will be,” he says. “With the healed DMEK graft in place you can treat the IOL calculations in the same manner as you would with a standard cataract surgery and you don’t have to account for the hyperopic shift since it already occurred.”

Cornea surgeons should also be on the lookout for epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. “If you notice on your Pentacam or other tomography device an irregular surface that’s not from swelling but from thickened basement membrane disease, it’s probably wise to do a corneal scraping first to get rid of that irregular, scabby material of the surface and let it heal over,” Dr. Terry says. “Once you have a stable surface without epithelial edema and without corneal epithelial scarring then you could go ahead and do your triple procedure based on those numbers.

“The triple procedure should only be done when you have a stable, smooth corneal surface and if you have an understanding of the hyperopic and sometimes slightly myopic shifts that a DMEK surgery can give you,” he continues.

Staging vs. Combined

There are some differences of opinion on when to proceed with the combined triple procedure and when to hold off, especially if the patient is expecting spectacle independence.

“The staging of the procedure can be done in one of two ways: you can perform the cataract surgery first or you can do the corneal transplant first,” explains Dr. Hannush. “Each one has a pro and con. When a patient is referred to me by a cataract surgeon, he or she is asking me two questions: how much of the visual disturbance is from the cornea and how much is from the cataract and, if mostly from the cataract, will the cornea tolerate routine cataract surgery? Usually, I can answer this convincingly—mostly cataract or mostly cornea. If it’s mostly cataract, I also have to tell the general ophthalmologist/cataract surgeon that the cornea may not withstand routine cataract surgery, even in their excellent hands. So, I may recommend they go ahead and do the cataract surgery, but the patient has to understand that the cornea may get cloudier and require an endothelial transplant secondarily. The cataract surgeon then decides whether to carry that decision-making burden or allow the cornea specialist to deal with it.”

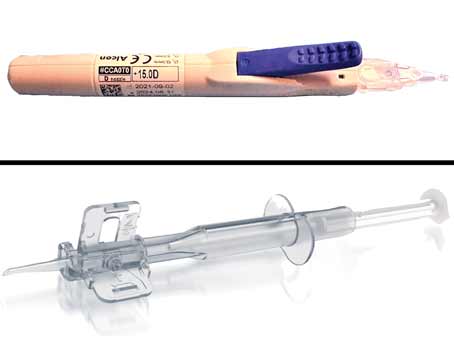

|

| A pre-loaded DMEK in a Geuder cannula is a commonly used device for DMEKs and triples as it fits through a 2.4-mm incision, according to Kourtney Houser, MD. Her technique includes unscrolling the graft and then using 20% SF6 gas, leaving about an 80-percent fill. (Courtesy Kourtney Houser, MD) |

In some cases, performing cataract surgery first might work in the patient’s favor, Dr. Hannush continues. “The advantage of doing cataract first is that the patient may not need an endothelial transplant,” he says. “They may get away with just cataract surgery, especially in Fuchs’ dystrophy. Assuming we have a virgin eye, if the Fuchs’ isn’t very advanced, most patients can get away with just cataract surgery, and they’re happy without subjecting them to an endothelial transplant at the same time. We let the patient know, however, that we can’t guarantee that the endothelial layer would survive, and they may need a corneal transplant secondarily.”

However, Dr. Hannush says the advantage of doing endothelial keratoplasty first, whether DMEK or DSAEK, is that if the cornea is the bigger contributor to visual loss, as opposed to the cataract, cataract surgery can be postponed at least temporarily. “Once the cornea clears after the DMEK, if the patient still feels the vision is suboptimal due to the cataract, accurate measurements with biometry of the implant power may be obtained and the cataract procedure planned,” he says. “You can even confidently place a toric or presbyopia-correcting implant if you do the cataract surgery secondarily. I’m personally not comfortable placing a specialty implant during a combined procedure. A toric IOL may be considered, but not a multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus lens, because the patient’s expectation is spectacle independence, which may not be achieved. With a staged procedure, doing the cornea first, the chances of achieving spectacle independence are decidedly better.”

Dr. Terry says he’s comfortable performing a triple procedure on patients with Fuchs’ and cataracts, provided there’s no disturbance of the epithelial surface. “The advantages of this strategy are: one trip to the operating room, which means one episode of risk for the patient and a much lower cost to the health system overall than two trips,” he says. “The majority of patients will get 20/20 vision and for those who get 20/25 vision instead of 20/20, they’re generally very happy with the result. So it’s a successful surgery. If they’re unhappy with their results because the refractive error is something that bothers them, then it’s easy enough to go ahead and do PRK or give them a pair of glasses.”

Undergoing DMEK has now made them a candidate for laser vision correction, Dr. Terry adds. “Their DMEK surgery has allowed the patient to move into a category such that they can have PRK or LASIK if they prefer not to wear glasses, whereas it’s contraindicated in my opinion to do refractive surgery in a Fuchs’ dystrophy patient that later will require a transplant,” he says. “Once you get rid of the Fuchs’ dystrophy and their eyes stabilize—and if they’re not happy about having to wear glasses to get 20/20 or 20/15 vision—then they can have refractive surgery just like anybody else. A vast majority of my patients decide that they’re happy with their surgery. If they have a slight refractive error, they’ll wear glasses on occasion, and they usually don’t want to have LASIK surgery or PRK surgery.”

Discussing refractive goals is a big component of the decision-making process for Kourtney Houser, MD, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Duke University School of Medicine. “I’ll stage the procedure if the patient is really motivated to be out of glasses, if they have significant astigmatism or if their cornea is already edematous and I’m not confident in the biometry for intraocular lens selection,” she says. “In staged cases such as these, I’ll do the corneal procedure first, typically a DMEK, allow the cornea to heal, and then once the cornea heals and stabilizes, I repeat biometry and tomography, make my intraocular lens selection and then perform the cataract surgery.”

Yet, she has a fair amount of patients who opt for the triple procedure because it significantly reduces the number of surgeries and visits to the office (from four surgeries to two in patients who need both eyes done).

Priorities might be a little different between patients who are eligible for DSAEK vs. DMEK. “My decision making for a triple procedure with DSAEK is similar to DMEK,” says Dr. Houser. “I’ll let them know the refractive goals with both, but in most cases, my DSAEK patients have very complex eyes with often lower visual potential than my patients who are undergoing DMEK. Because of the often-present glaucoma or retinal disease in patients undergoing DSAEK, our goal is usually not spectacle independence but instead maximal visual rehabilitation.”

IOL Recommendations

Once you’ve determined whether the patient’s procedure will be staged or done simultaneously, it’s important to consider which types of IOLs to implant and which to avoid.

Dr. Terry most often reaches for a toric IOL in the combined triple procedure. “Toric lenses are fine to do in triple procedures,” he says. “We’ve published a couple of studies on the use of toric lenses in EK surgery. This is different from using multifocal IOLs in a DMEK triple. I don’t recommend multifocal lenses if you’re going to do a triple procedure because it’s not going to be accurate enough for your keratometry values as it would be in a staged procedure. If you have a patient who absolutely demands having a multifocal lens, then that makes sense to be doing a staged procedure of a DMEK and wait for everything to heal before implanting a multifocal.”

Alternatively, Dr. Houser is more conservative with her IOL choice, leaning toward monofocals without toricity in triple procedures. “If a patient is interested in spectacle independence and it appears they’d require a toric lens to achieve this, I tend to stage the procedures instead of combining them,” she says. “Any hydrophobic acrylic intraocular lens is safe to use, but I avoid hydrophobic acrylic lenses, as these can calcify and opacify with gas injection. If I had access to the Light-Adjustable Lens, I think this would be an excellent place for it. The astigmatism and spherical power of the lens could be adjusted postoperatively and we could perhaps combine more of these cases. My only hesitation would be that occasionally a patient can develop an area of posterior synechiae with DMEK, which would prevent postoperative adjustment of the lens.”

A study on the first reported cases of a DMEK triple procedure using the Light-Adjustable Lens (RxSight)2 suggested positive outcomes, with Patient A achieving a distance UCVA of 20/15 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye, and Patient B (targeted for monovision) achieving a distance UCVA of 20/15 in the dominant eye and a near UCVA of Jaeger No. 1+ in the non-dominant eye, after final lock-in. However, the study did cite risks, including the chance of the IOL moving anteriorly and contacting the graft, as well the burdens of multiple visits and out-of-pocket expenses on behalf of the patient.

Intraoperative Medications

Administering medications during a triple procedure is very different from performing routine cataract surgery.

Firstly, topical anesthesia may not be enough. “Most corneal surgeons perform the triple procedure with regional anesthesia, meaning a peribulbar block,” Dr. Hannush says. “There are some surgeons who will do it under topical anesthesia, which isn’t unreasonable, but it’s a longer procedure than a 10-minute cataract and requires more patient cooperation.”

Then there’s the matter of dilating and constricting the pupil. “In the triple procedure you’re balancing the need to have a pupil dilated for the cataract surgery with the need to have the pupil very small for unscrolling your DMEK graft tissue,” says Dr. Terry.

“When doing a triple, I use different dilation drops and intraoperative medications than in my routine cataract surgery cases,” Dr. Houser says. “In a normal cataract surgery I use a mix of tropicamide/phenylephrine and cyclopentolate to dilate patients in the preoperative area and in some cases use Shugarcaine or a mix of phenylephrine/ketorolac intraoperatively. This allows for long-lasting pupillary dilation. If I’m doing DMEK along with cataract, I’ll only dilate with phenylephrine and use plain preservative-free lidocaine for intracameral anesthetic to allow for easier pupillary constriction following the cataract portion of the case.

“The cataract procedure can sometimes be a little more challenging because of the often poorer dilation, but it’s usually sufficient to safely do the surgery,” she continues. “I add Shugarcaine to supplement dilation if I can’t safely do the case with the level of dilation. After the cataract surgery is complete, I use Miostat or Miochol to induce pupillary constriction.”

The cornea specialists we spoke with all emphasized that it’s best to avoid cycloplegics in a triple procedure. “Those are powerful dilators, so it’s harder to constrict the pupil afterwards,” says Dr. Hannush. “Also, it’s best to avoid the use of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, although commonly used during cataract surgery to avoid loss of dilation. At the time of graft insertion during DMEK, it’s nice to have a constricted pupil. Miotic agents aren’t strong enough to bring the pupil down if you have a cycloplegic and/or NSAID on board.”

Dr. Terry advises, “If you were to use cycloplegic drops in addition to the phenylephrine drops to dilate the pupil, you paralyze the sphincter muscle and you stimulate the dilator muscle of the iris. Then it’s much harder to get the iris to constrict down for the injection and unfolding of the DMEK tissue and I think that’s a dangerous proposition.”

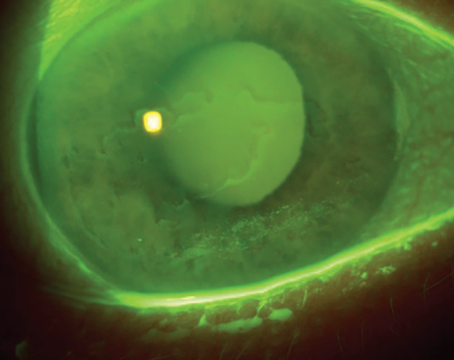

Dr. Houser offers another tip for the cataract surgery itself: “If there are visually significant guttae or corneal edema, I have a very low threshold for using trypan blue to make the cataract surgery a little bit easier,” she says. “I’m also very cautious not to oversize my capsulotomy or capsulorhexis to keep the intraocular lens stable during the DMEK procedure. If you oversize the capsulotomy, the IOL can prolapse forward during the DMEK procedure and damage the graft.”

One of the advantages of performing DMEK as a component of the triple procedure is that patients can be taken off their topical medications much quicker than a full thickness or even a DSAEK transplant. “The rejection rate is much lower,” Dr. Hannush says. “We usually use the NSAID for a couple of weeks and the antibiotic for one week but, as opposed to keeping them on the steroid four times a day for at least three to six months after a full-thickness graft, they can be tapered down to twice a day, even once a day by three months after DMEK. If they’re a steroid responder, with an intraocular pressure rise, you can even stop the steroid after a few months. The rejection risk is less than 2 percent. If you stop the steroid on a full-thickness transplant in three months, the rejection rate is significantly higher.”

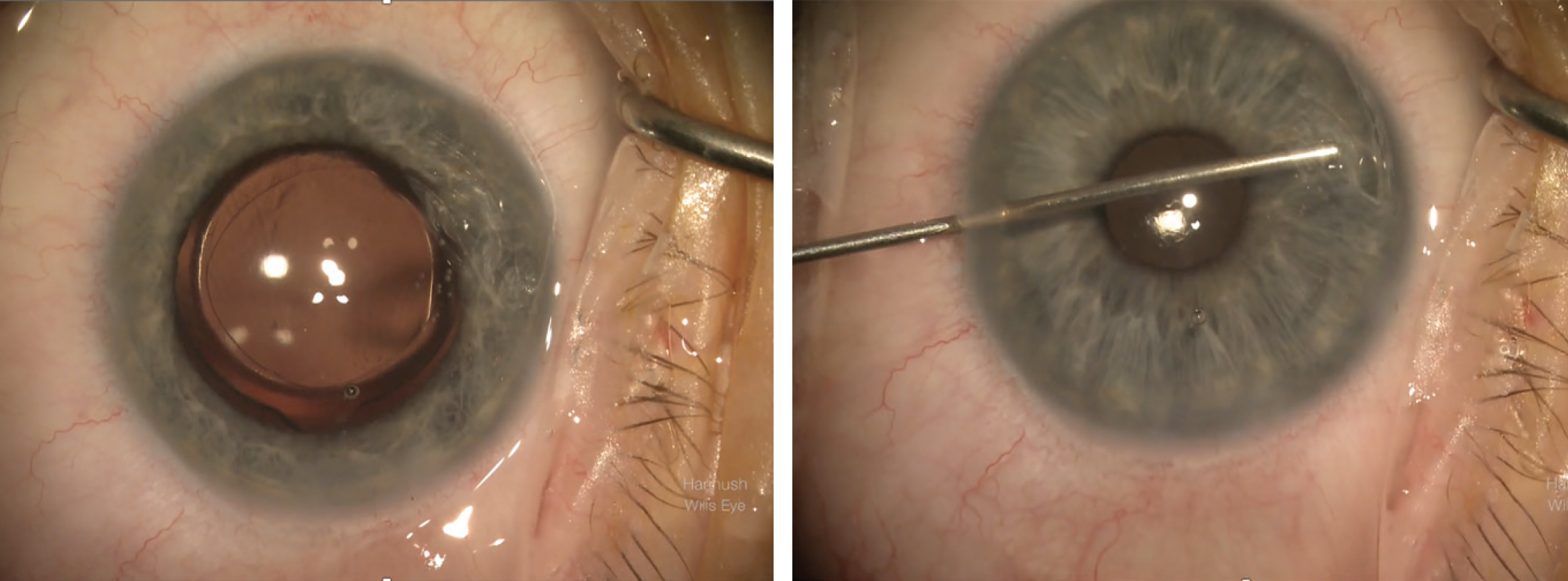

|

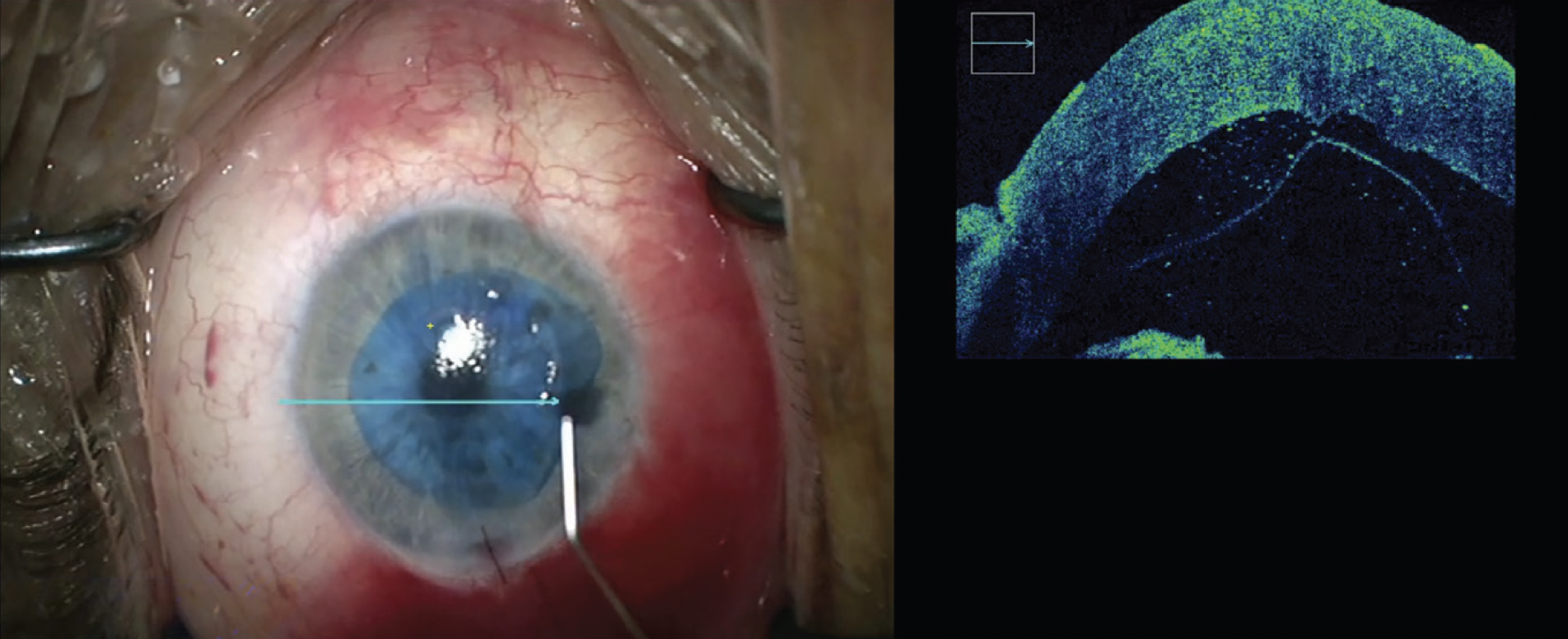

| Some surgeons will use a microscope-mounted OCT to view the graft inside the anterior chamber to ensure it’s in the correct orientation with the endothelial side toward the anterior chamber. (Courtesy Sadeer Hannush, MD) |

Technique Pearls

We asked these experts for best practices and strategies they’ve honed over the years of performing the new triple procedure. Here’s what they said:

• Graft insertion. “Most of us are using a small incision for DMEK, usually 2.4 mm, and inserting the graft with a glass tube,” says Dr. Hannush. “The most popular one is made by Geuder from Germany, but there are other glass tubes. Some surgeons insert the DMEK graft with a modified IOL inserter.”

“When I first started doing DMEK I didn’t have access to the Geuder cannula,” notes Dr. Houser. “I initially used a Modified Jones Tube, which is a great insertion device, but it requires a little larger incision. I would typically enlarge the incision I made for my cataract surgery prior to insertion, and if the wound size didn’t perfectly match the cannula size for insertion of the graft, it was easy to prolapse the graft out of the eye. But now that the Geuder is available, I think that’s really made things a lot easier. The incision/inserter size match creates a stable anterior chamber for graft insertion and makes it more challenging to prolapse the graft out of the eye.”

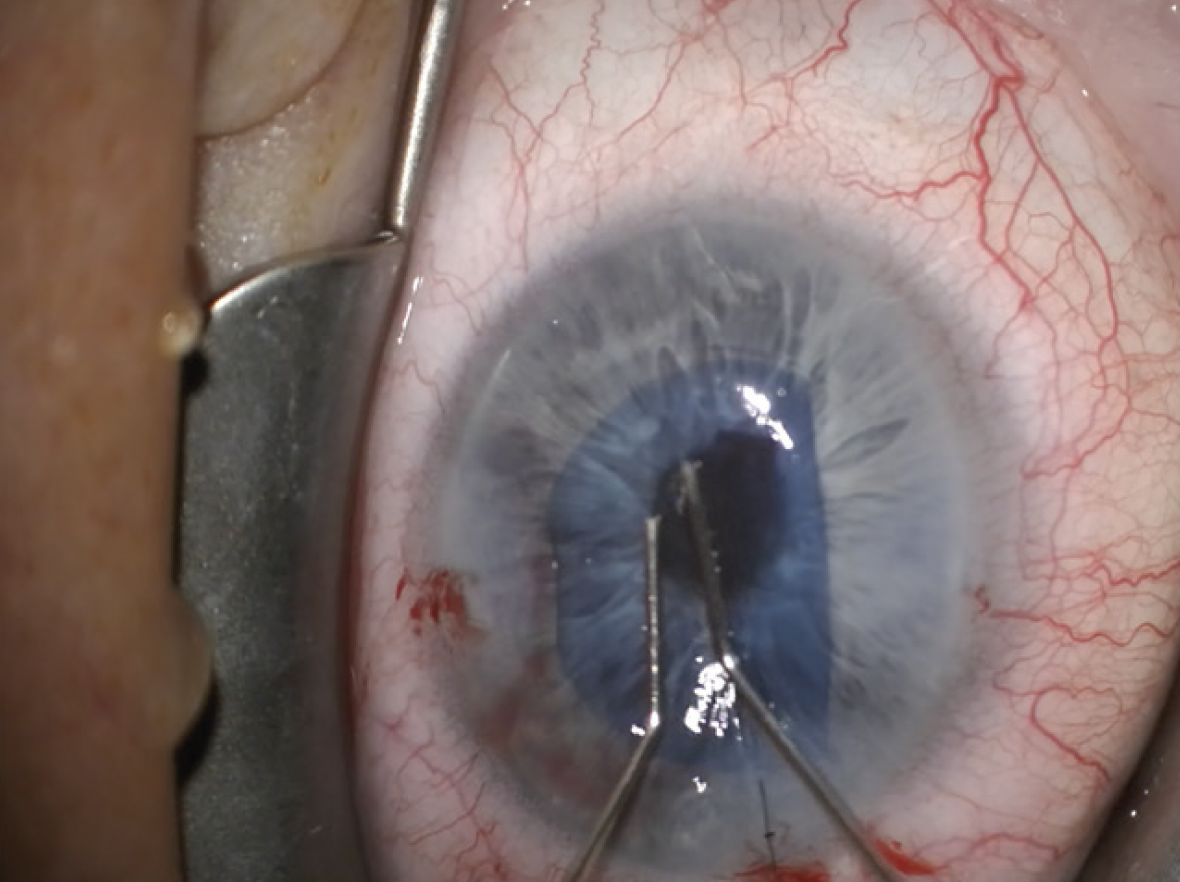

She further explains her process, including the use of SF6 gas, saying, “After pupillary constriction, I perform an inferior peripheral iridotomy with a side-port blade after gently elevating the iris with my endothelial stripper,” Dr. Houser says. “I mark the cornea with an 8-mm marker to mark my area of endothelial stripping, which is 0.5 mm larger than my typical graft size. I use the Fogla stripper for endothelial stripping, which has a nice ball on the tip that prevents penetrating too deep into the stroma. I take extra care to thoroughly remove all viscoelastic prior to graft insertion. Then I use a pre-loaded DMEK in a Geuder cannula as it fits through a 2.4-mm incision, which is my preferred incision size for cataract surgery. I unscroll the graft and then use 20% SF6 gas for all my DMEK procedures, including DMEK triples, leaving about an 80-percent fill. There’s data that shows equivalent rebubble and graft survival rates with air, but I like using the SF6 because it stays in the eye a little bit longer. Finally, I have the patient sit for an hour face up in recovery before discharge.”

• Stripping and unscrolling techniques. “When stripping host Descemet’s, most of us agree that you want to strip a larger area than the area you’re transplanting,” Dr. Hannush says. “For example, I’ll strip a diameter of 8.5 mm and I will graft a diameter of 7.75 to 8 mm, so I over-strip by 0.5 to 8 mm.”

For unscrolling, Dr. Hannush suggests surgeons investigate the variety of techniques that have been published, including:

• a single-handed insertion of the graft into the anterior chamber. The surgeon then uses a combination of tapping on the central cornea, sweeping an instrument across the host cornea over the graft, or injecting fluid in different directions to unscroll the graft. A cannula with a pair or more side ports may be inserted into the scroll followed by a little puff of fluid to unscroll the graft;

• a pull-through technique, where the graft is placed in a modified DSAEK injector cartridge then pulled into the anterior chamber with a forceps; and

• using a microscope-mounted OCT to view the graft inside the anterior chamber and make sure it’s in the correct orientation with the endothelial side toward the anterior chamber.

“One personal preference of mine is to suture the main incision with DMEK,” says Dr. Houser. “I find it easier to unscroll the graft when I have an extra incision through which to inject or release BSS from the anterior chamber.”

The Next Frontier

Just as DSAEK and DMEK revolutionized cornea transplantation two decades ago, the next phase of innovation is already underway.

“Allogenic endothelial cell therapy is the next frontier in corneal endothelial replacement,” says Dr. Hannush. “Based on the work of Professor Shigeru Kinoshita in Japan, mature corneal endothelial cells from a healthy donor may be cultivated in vitro then injected intracamerally into the eye of a recipient with endothelial dysfunction. This leads to clearing of the cornea and restoration of vision. The excitement surrounding this technology is that one donor cornea may provide healthy, differentiated endothelial cells for 100 or more recipients, eliminating the worldwide shortage of donor tissue for transplantation.”

“Human trials have started in the U.S. recently, and data from the initial work in Japan is very exciting,” adds Dr. Houser. “There are a lot of patients with severe glaucoma or other ocular comorbidities who aren’t great candidates for endothelial keratoplasty due to risk of pressure increase or who’ve already undergone several surgeries and one more may be a higher risk. The availability of an injection of cells that wouldn’t require significant pressurization of the eye would be very beneficial for these patients. DMEK has been such a big improvement over DSAEK, and I’m excited for our next advancement."

Dr. Hannush has no related disclosures. Dr. Houser reports a relationship with Rayner. Dr. Terry has no financial interests.

1. Terry MA, Shamie N, Chen ES, Phillips PM, Shah AK, Hoar KL, Friend DJ. Endothelial keratoplasty for Fuchs’ dystrophy with cataract: Complications and clinical results with the new triple procedure. Ophthalmology 2009;116:4:631-9.

2. Eisenbeisz HC, Bleeker AR, Terveen DC, Berdahl JP. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty and light adjustable lens triple procedure. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2021;25:22:101061.