As of this writing, the implantable Contact Lens (Staar Surgical, Monrovia, Calif.) appears to be within weeks of final approval in the United States, and many surgeons are eager to see how it performs in their patients. Though the ICL procedure is relatively straightforward, there are several finer points to be aware of. In this article, I'll share these points with you, based on my experience as the medical monitor of the ICL's U.S. Food and Drug Administration clinical trial.

Preop Matters

For most surgeons, the typical ICL patient will be someone whose myopia is so high that LASIK may not be the best procedure for him because of the risk of postop ectasia from the removal of too much corneal tissue. This upper limit varies from surgeon to surgeon, though it's rare for someone to perform LASIK on a patient as high as -14 D. Instead, most surgeons may reach for the ICL in patients over -10 D or even -8 D. However, as surgeons become more comfortable with implanting ICLs, we may see the pool of candidates expand. In a similar way, LASIK's pool expanded as surgeons grew comfortable with it and began using it for lower myopes, rather than reserving it simply for those higher myopes in whom PRK might cause haze.

• Requirements. Anterior-chamber depth is also a factor. The recommended depth is 2.8 mm, and I think 2.6 mm is the minimum depth at which I'd feel comfortable implanting a posterior-chamber phakic intraocular lens like the ICL. In reality, though, since myopic patients tend to have longer eyes and deeper chambers, this minimum depth requirement tends not to be a limiting factor for them.

|

| The ICL may give refractive surgeons an option in high myopes at risk for ectasia. |

The approved patient age range will be from 21-45. The likely approved range of powers should be from -3 D to -20 D at a 12-mm vertex distance. The actual maximum amount of correction that the lens will be able to achieve optically, however, will be about -17 D. This discrepancy is due to the slight difference between how the lens is labeled and the actual intraocular power at the nodal point in the eye. This is similar to the labeled powers of IOLs for cataract surgery, which aren't always identical to the correction the patient needed before surgery.

• Sizing. This is a very important measurement, because sizing will determine the fit and overall success of the procedure. Selecting the appropriate lens size is based on a measurement of the patient's white-to-white distance, which is just an indirect measurement of the sulcus-to-sulcus length. After hundreds of patients, we've determined that the best white-to-white measurement is done with calipers under loupe or microscope magnification, with the patient in a reclined position. We discourage the use of gauges or automated instruments such as the Orbscan or the IOLMaster, because the former are subject to parallax error and the latter can be misled by a pterygium or by limbal neovascularization associated with long-term contact lens use. Currently, it looks as if the ICL will be available in sizes ranging from 11.5 mm to 13 mm in 0.5-D steps.

When I'm sizing an eye, I generally round up if the value is between two available lens sizes. However, sizing is somewhat influenced by anterior-chamber depth. So, if someone has a larger-than-median AC depth, I'd round up; if shallower, I'd round down.

To make selecting a lens easier, Staar is planning to have an on-line sizing and ordering system. The surgeon will go to a website, enter in the patient's biometry, such as chamber depth and white-to-white measurement, and the program will select the appropriate ICL to order. The U.S. on-line system isn't finalized yet, but it's already available for European users.

Tips for Implantation

Though surgeons will be comforted knowing that many of the steps involved with ICL implantation are similar to implanting an IOL during cataract surgery, there are some new steps. Here's a rundown.

• Iridectomies. To ensure that the flow of aqueous isn't blocked as a result of the procedure, you'll need to make two peripheral YAG iridectomies at the 11 o'clock and 1 o'clock positions

|

| It's important to slowly inject the ICL into the anterior chamber over a period of 10 to 15 seconds. This ensures an atraumatic delivery. |

The iridectomies are best done before the surgery because of some inherent challenges of doing them simultaneous with ICL implantation. For instance, if you were to wait until surgery to do them, you couldn't perform them until after the implant is placed. And, because the eye would be dilated by then, the surgeon would have to bring the pupil down. But, since we don't always get complete miosis, it would be difficult to make a uniform, small-enough PI. The other issue is that a temporal, clear-corneal incision makes it more challenging to create a superior PI.

A final preop point: On the day of surgery, the eye has to be sufficiently dilated in advance of the procedure for the pupil to maintain dilation throughout the operation. Mydriatic drops every 10 minutes for a minimum of three applications will allow maximum dilation.

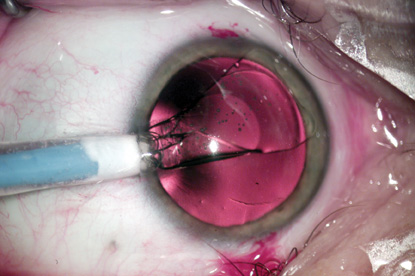

• Loading the injector. The ability to deliver the lens in a controlled manner depends on the care you take when loading the injector preoperatively.

Since the ICL is very thin, it handles differently than a regular IOL. So, while many cataract surgeons may delegate the actual loading of an IOL cartridge to a technician, we strongly encourage that the ICL surgeon himself load the injector under magnification.

When loading the lens, it needs to be aligned straight in the cartridge and not be bound on its edges or by the plunger that advances it. If it becomes twisted or gets into a "dish-rag spiral," the ICL will continue this spiral as it's advanced down the cartridge, possibly resulting in an inverted delivery. Or, if the footplates aren't aligned correctly, they could fold upon themselves and perhaps sweep over the crystalline lens or onto the cornea in a way that would be less controlled than you'd want. By taking an extra minute or two under magnification to load the lens properly, however, you can easily avoid these problems.

|

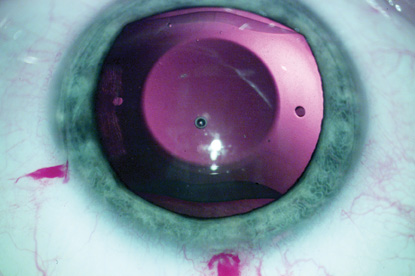

| Once the ICL is sitting in the anterior chamber, the surgeon uses a special manipulator to sweep the lens's footplates behind the iris. |

• Incisions. A 3-mm temporal clear corneal incision is best, because it orients the lens parallel to and above the iris plane, in the anterior chamber. If it were directed posteriorly, it might strike the crystalline lens. A sideport incision is helpful to gain access to the implant once it's in the anterior chamber to allow you to position it behind the iris. Though I usually recommend two sideports, many surgeons have found one is sufficient for them to position the lens comfortably.

• Injecting the lens. Before you inject the ICL into the eye, inject some viscoelastic to help maintain the chamber. Additional viscoelastic during the procedure can be helpful as well, since some of it may escape during the implantation.

Insert the cartridge and slowly inject the ICL into the anterior chamber. I recommend injecting it over a 10- to 15-second period. Though this may not sound like a long time, when it's compared to the short time taken to inject an IOL during cataract surgery, it actually feels quite slow. However, a deliberate injection allows a very controlled positioning of the lens as it exits the inserter, and ensures an atraumatic release into the eye.

• Positioning the lens. Once the lens is in the anterior chamber and is sitting slightly above the iris plane, place some additional viscoelastic on top of it, between the lens and the corneal endothelium. This viscoelastic helps settle the lens further posteriorly and brings its footplates closer to the level of the iris.

The next step involves sweeping the lens into its final resting spot behind the iris, and there are specialized instruments to help facilitate it. These devices include the Dietz ICL Manipulator (Katena Products; Denville, N.J.), the Vukich ICL Manipulator (ASICO; Westmont, Ill.) and the Pallikaris ICL Manipulator (Duckworth & Kent USA; Saint Louis, Mo.). To execute this maneuver, you grasp the lens with one of these instruments and, with a sweeping motion, bring the footplates into a position posterior to the iris.

One of the biggest initial challenges with ICL implantation is altering your cataract-surgery mindset. Rather than being able to touch the crystalline lens with impunity as in cataract surgery, you now have to respect both the corneal endothelium and the natural lens. You must try not to cross the central 6 mm of the crystalline lens or touch the anterior lens capsule. You have to do all of your manipulations peripherally, rather than in the center as in cataract surgery.

Once the lens is behind the iris, the surgery is nearly complete. The lens will seat itself in the ciliary sulcus. At that point, use a miotic agent like Miochol to bring down the pupil. Though there will be some viscoelastic between the ICL and the natural lens, I don't recommend going after it. It's best not to place any instruments or direct any hydrostatic force behind the ICL once it's in position to avoid trauma to the natural lens.

The dynamics of the Miochol in the eye and, possibly, the small amount of viscoelastic that remains, will affect the apparent fit of the lens. These dynamics will stabilize within a few hours, however, and the implant will find its final position.

See the patient two hours later to make sure there's no spike in intraocular pressure from retained visco or from incomplete PIs. Put the patient on the usual prophylactic antibiotic and anti-inflammatory drops for five to seven days.

Postop

On the first postop day, visual quality is usually quite good. I usually see the patient at one or two weeks, then as clinically indicated after that.

• Results and complications. In our U.S. study of 526 eyes of 294 patients, 85 percent saw 20/40 or better and 45 percent saw 20/20 or better uncorrected at six months.

At this point, the ICL's complication rate has been acceptably low. Specifically, in the FDA study, the rate of cataract formation requiring secondary intervention was 0.6 percent. We haven't seen any IOP elevations. Endothelial cell counts have stabilized over a three-year follow-up period, though they should always be watched carefully both pre- and post-implantation. Less than 1 percent of the patients developed postoperative complications, including one macular hemorrhage and three retinal detachments. There will be a learning curve along which you may experience some complications as you become more familiar with the procedure. When you get a sense for the technique, though, complications will be low.

One of the positive postop findings is that there doesn't seem to be a pupil-size issue with the ICL. Even though it's common for scotopic pupils to be wider than the diameter of the ICL's optic, complaints of glare and night-vision problems were very rare in the clinical study.

In the FDA trial, the overall rate of removal and reimplantation was 2 percent. These reinsertions were due to lenses being inserted upside down, and mostly involved cases early on in the development of our technique. Now, however, we've developed a delivery system in which putting them in inverted isn't much of a concern.

If you decide to get involved with the ICL, I hope the tips I've provided help you hit the ground running when it's finally approved.

Dr. Vukich is a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine, and is the director of refractive surgery at the Davis Duehr Dean eye center. As medical monitor for Staar's U.S. trial, he has a financial interest in the ICL.