The greatest fear of all is that of the unknown. Unfortunately, the unknown is exactly what herpes simplex virus sufferers face, and what we ophthalmologists have to deal with. Herpes can lie dormant for years, then, triggered by an as yet unknown mechanism, manifest itself in the eye with debilitating results. Since our best defense against the unknown is knowledge, this article reviews ocular HSV infection and the most effective methods of treating it as revealed by the Herpetic Eye Disease Study, in which I took part.

Herpes: A Broad Spectrum of Disease

HSV eye disease is a wide spectrum of clinical problems ranging from dermatitis of the eyelid, blepharitis of the lid margin, conjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis and iritis. Herpes is responsible for such a variety of ocular effects that it overlaps with many other eye diseases, and is often on the differential diagnosis of any kind of inflammatory eye disease of the anterior segment that has an unclear etiology.

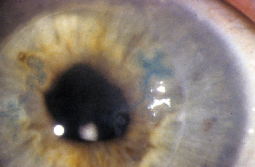

|

| Several bouts of herpes stromal keratitis can result in a metaherpetic ulcer. The ulcer is marked by smooth edges over an area of stromal inflammation or scarring. |

This article mainly deals with corneal HSV disease, of which there are two more common kinds: an epithelial infection that often takes the form of a dendrite and makes up about 80 percent of ocular HSV cases; and a stromal keratitis, which occurs in approximately 15 percent of cases and ranges from disciform edema to focal corneal infiltration. Around 5 percent of HSV patients have blepharitis, conjunctivitis or a combination of the two. A small proportion of patients, around 1 percent, may have either iritis alone or keratouveitis—serious iritis concomitant with epithelial or stromal disease. The most common form, the dendrite, is generally easy to recognize and to treat, and usually has a lesser impact on vision in comparison to stromal keratitis.

HSV Treatment

When a patient first presents with an HSV episode, either epithelial or stromal, it may appear to be the first occurrence. Virologically, however, it's a recurrence. The primary infection to the face, mouth, eye or nose often goes unnoticed to the patient, and the herpes settles in the central nervous system where it remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion for the rest of the person's life. Then, decades later, it will reactivate and cause the disease you see in the office.

The dendritic form and the stromal keratitis typically occur as separate diseases. Originally, we thought that the epithelial infection came first, with the cornea acting as a sort of blotter, soaking up viral antigen and setting up an immune reaction in the stroma that arose once the epithelium healed. We now know that it's not that simple. Some patients can develop stromal keratitis or endotheliitis without any previous apparent epithelial keratitis and vice versa. Occasionally, they happen together, which presents a very difficult case to treat.

Though researchers have tried to uncover what triggers a recurrence, the question continues to confound. Some have suggested that ultraviolet light exposure may cause recurrences, as we know that dermatologists in Colorado see a lot more recurrent herpes of the skin and face when people go skiing and are exposed to large amounts of UV. Some animal studies corroborate the UV light link. The HEDS analysis, however, found no clear-cut link between ocular herpes and sunlight, fever, stress or other suspected triggers. After a recurrence, people may selectively recall an event that may not be causal.

Here are our current treatment strategies.

|

| Herpes can lie latent in the trigeminal ganglion for decades before erupting into a recurrence such as this epithelial dendrite. The dendritic form of herpes recurrence accounts for around 80 percent of cases, but is the least likely to permanently damage vision. |

Though U.S. clinicians don't have easy access to acyclovir 3% ophthalmic ointment that's available in other countries, in the final analysis it may not add that much to our treatment. Even though the ointment requires less-frequent dosing (four or five times daily vs. q2h for trifluridine) and there's a consensus that it's safer in terms of toxicity when used over the long term, our usual treatment course is only short term in the vast majority of cases.

The visual and anatomical outcomes for patients with the dendritic form of the disease are good. There is very little permanent vision loss, though the decreased vision can be dramatic during the course of the disease. After the two weeks or one month of treatment, the visual outcome is usually excellent.

|

| Herpes necrotizing stromal keratitis is more severe than the dendrite and can result in permanent decreased vision. |

• Stromal keratitis. For this less common but more sight-threatening form of herpes recurrence, treatment with corticosteroids offers a significant benefit, as demonstrated by the Herpetic Eye Disease Study (See "HEDS Sheds Light on Herpes"). If the stromal disease is concomitant with the epithelial dendrite, however, using steroids will make the situation worse. In such cases, it's best to wait until the epithelial infection has healed before treating the stromal inflammation.

| HEDS Sheds Light on Herpes |

|

The Herpetic Eye Disease Study was a series of randomized, double-masked placebo-controlled clinical trials that looked at various approaches to treating ocular herpes simplex virus keratitis. Here is a breakdown of key findings that can be directly applied to clinical practice. 1. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 1994;101:1883-96. |

My steroid regimen initially consists of 1% prednisolone four to eight times a day. I then taper the steroid fairly rapidly over 10 weeks, from eight times daily to six, then to q.i.d., b.i.d., and q.d. In the HEDS, this regimen was only effective for half of the patients; the other half needed a slower taper and a longer treatment course for their inflammation to eventually resolve.

Some patients need chronic low-dose steroids to maintain their uninflamed state, but, unfortunately, we don't yet know how to recognize these individuals. The steroid course I outlined may be too slow for some or too rapid for others, so I do it on a case-by-case basis, basing the decision on the level of disease severity and the pace of patient improvement.

Visual outcomes in patients who develop the stromal form of HSV keratitis aren't as good as those for the epithelial infection. Many stromal keratitis patients will have a residual corneal scar that can cause substantial vision loss if it's located in their visual axis.

Further episodes of the stromal form can cause progressive vision loss due to the toll they take on the cornea over time with repeat recurrences. It's in these stromal keratitis patients that I'm more aggressive with my prophylactic use of oral acyclovir, as explained below.

HSV Prophylaxis

Another important finding of the HEDS was the effectiveness of antiviral prophylaxis in preventing recurrences of HSV disease. After a patient's disease has healed, I place him on a regimen of 400 mg of acyclovir b.i.d. for a year. This reduces the chance of a recurrence by as much as half. This can be especially beneficial for patients with a tendency toward recurrences of HSV stromal keratitis, the more sight-threatening form of the disease.

• New antivirals. The study has yet to be conducted in ophthalmology that looks at oral valacyclovir (Valtrex, GlaxoSmithKline) and/or famciclovir (Famvir, Novartis) for preventing recurrent ocular herpes. Extrapolating from genital herpes recurrence studies, however, it appears that these new agents may be just as, or potentially slightly more, effective than acyclovir, but they also cost a bit more.

The intensified interest in Famvir arises from animal studies in which the agent appeared to have some inhibitory effect on the latent virus in the central nervous system, a mechanism of action acyclovir doesn't offer, since it only works on active virus.1-3 Whether Famvir's effect on latent virus also applies to HSV in humans, however, is still unclear.

Right now, we clinicians have to continue to combat herpes with the agents that are available to us. Eventually, however, a better understanding of the virus as well as more potent drugs that can strike at it while it's in its latent phase may allow us to considerably weaken the disease's ability to cause ocular damage upon its recurrence.

Dr. Wilhelmus is a professor of ophthalmology at the Baylor College of Medicine.

1. LeBlanc RA, Pesnicak L, Godleski M, Straus SE. The comparative effects of famciclovir and valacyclovir on herpes simplex virus type 1 infection, latency, and reactivation in mice. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:3:594-9.

2. Thackray AM, Field HJ. Famciclovir and valaciclovir differ in the prevention of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in mice: a quantitative study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998;42:7:1555-62.

3. Loutsch JM, Sainz B Jr, Marquart ME, et al. Effect of famciclovir on herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal disease and establishment of latency in rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001;45:2044-53.