The Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, is the government’s latest attempt to encourage doctors to adopt the best, most efficient and (hopefully) least-costly medical practices possible. Created as part of the Medicare Access and CHIP reauthorization Act (MACRA), MIPS is one of two payment tracks doctors can follow in the Quality Payment Program, which was implemented to replace the now-defunct sustainable growth rate system. (The other track in the QPP is the Advanced Alternative Payment Model, discussed below.)

MIPS adjusts Medicare reimbursements based on how physicians score in four categories: quality of care;

As with any complex system in which doctors must operate, understanding the system is essential to producing a positive result. Here, experts answer 12 key questions ophthalmologists are asking about the MIPS system and how they can best navigate it.

1 How is MIPS impacting ophthalmologists so far?

“Initial implementation of MIPS hasn’t been as disruptive as some feared it would be,” says Mark B. McClellan, MD,

“Many measures are requiring less reporting than people expected,” he continues. “Some of the measures have been revised with the goal of being more relevant to supporting good practice, and CMS has encouraged providers to focus on the measures they view as relevant. That helps to get better alignment between what providers are being asked to report and what they actually report on. For example, rather than ask doctors to go down a checklist of characteristics of their EHR system, there are fewer reporting measures related to electronic data, and the ones that remain are more focused on whether data is being shared among health-care providers the way it should be.”

Michael X. Repka, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and a professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and medical director for government affairs at the American Academy of Ophthalmology, suggests that it’s helpful to think of the participants in the program as falling into several categories, each of which may be having a completely different experience. “One category is ophthalmologists who are in big academic groups or multi-medical-specialty groups—in other words, groups that are not composed entirely of ophthalmologists,” he explains. “They’re working under a group-reporting option, so they don’t actually do very much directly. That’s the type of practice group I fall into; I rely on what the clinical practice association does in terms of more general medical performance measures, along with EHR use. [Dr. Repka notes that this is considered MIPS “group reporting,” as opposed to an APM arrangement.] As far as I understand, ophthalmologists in academic-center situations or large multispecialty medical practices are doing well. They’re potentially looking at up to a 2-percent bonus in 2019, based upon 2017 performance measurements. That will be a substantial amount of money.

“The majority of ophthalmologists in small-to-midsized practices who have EHR and participate in IRIS are reporting that they did fine in 2017,” he continues. “As much as a 2-percent bonus is realistic for next year. Many of these practices may also be getting into the super-threshold bonus; that’s the $500 million

“If you’re hoping to make a living off of these bonuses,” he adds, “you’ll be disappointed. They’re too small.”

Jeff Grant, president and founder of

2 How much of an advantage is it to have EHR and participate in IRIS?

“In the current MIPS system, ophthalmologists have been lucky,” says Mr. Grant. “Ophthalmologists have done exceedingly well. The biggest reason for that is the IRIS registry, supported by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. When IRIS first came along four or five years ago, back before we had MIPS, it only helped doctors with the quality-reporting portion. Today, IRIS has made it possible for providers to submit not just quality measures, but also data related to the old meaningful-use measures, now called ‘promoting interoperability,’ or PI. IRIS can extract the appropriate data from the EHR data and map it to that specific practice’s reports, which is important because even if two practices have the same EHR product, they may enter the data a little bit differently. IRIS can account for that and then submit everything for them. It’s been a fantastic tool.

|

| Click to enlarge. |

“By way of comparison, consider the field of optometry,” he says. “The American Optometric Association has struggled for several years to create something similar to IRIS, and it hasn’t worked out nearly as well; I don’t know why. But it makes me feel even better for ophthalmologists when I see what IRIS is able to do for them. IRIS has probably been the single best thing for ophthalmologists in regard to all of these federal programs, whether you’re talking about PQRS or MIPS.”

Mr. Grant says that when ophthalmologists have an issue with MIPS, it’s usually related to things that are unique about their particular practice. “Maybe the practice isn’t using EHR,” he says. “That would be a big problem and make MIPS very difficult, because even if the practice submits data through IRIS, IRIS can’t extract the relevant MIPS data. The practice would have to come up with information on quality and the former meaningful-use measures on its own, and that can be problematic.”

Mr. Grant notes that difficulties with the program caused by lack of an EHR system might soon become worse. “In order to avoid a penalty, a practice without EHR has to send quality measures via claims data,” he says. “I have a couple of clients who’ve chosen not to use EHR and continue to send quality codes via claims. They’ve been relatively untouched—no penalties, no incentives. However, there’s a proposed rule that just came out that would eliminate claims-based reporting for the quality measures. If that rule is implemented, a practice without EHR wouldn’t have any way to submit their data; they’d have no way to prevent a penalty. The only option they’d have left would be to come up with some reporting mechanism using their software that generated numbers they could manually enter into the IRISwebport. That’s possible, but again, how much time and expense would it involve?

“For now, they might decide that taking the penalty is better than spending the money,” he concludes. “But as the penalties continue to increase in the coming years, the pain is going to increase. Those practices may change their minds two years down the road.”

3 How is

The “budget neutrality” built into the MIPS system, which adjusts the overall payments to ensure that the system only gives out a certain amount of money, has made the incentives and penalties unpredictable. “The physicians who do better on the MIPS measures are paid more at the expense of those who do worse,” Dr. McClellan points out. “The measures reported are supposed to reflect differences in quality of care, but initially physicians were concerned that not reporting correctly might lead to a significant reduction in payments. What CMS is finding is that most physicians who do report are doing pretty well in the measures. In addition, there are many physicians who don’t have to report as much because they have very small practices that don’t see a lot of Medicare beneficiaries. The result is that the differences in payments that are emerging for physicians based on MIPS are not as large as expected. It looks like not too many physicians will face big penalties, and conversely, not too many will get large bonuses, either—at least for the next few years.”

Mr. Grant notes that in the first year, it was publicized that doctors could earn up to a 4-percent bonus in 2019, based on their 2017 reporting. “It turned out that because a large number of practices did well, the largest incentive bonus was 2.02 percent,” he says. “That’s the most anyone got, and that includes some additional money that wasn’t part of the budget-neutrality deal.”

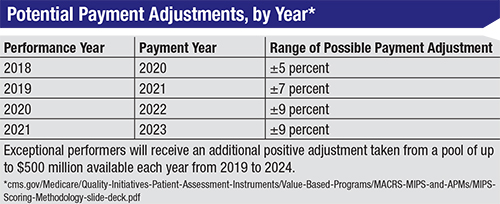

Mr. Grant says many practices were surprised. “The fact that the bonus amount could be lower if a lot of practices met the criteria was not well publicized,” he notes. “The possible bonus was actually ‘up to’ 4 percent. Next year, it’s supposed to be ‘up to’ 5 percent. We won’t know what it actually is until the reporting is done and they know how many practices reached certain levels and how many were poor performers.

| “The fact that the bonus amount could be lower ... was not well publicized.” —Jeff Grant |

“Of course,” he continues, “many practices based their calculations on getting a 4-percent bonus. At the same time, some practices wanted to know what the maximum pain would be if they chose not to do this—especially doctors in their last three to five years of practicing. They’re winding down and they don’t want to go through all of these changes, so they have us try to figure out what the maximum penalty might be. It’s now clear that if you base either calculation on the announced maximum benefit or penalty, your numbers will be off. We won’t know what the maximum will actually be until the reporting for the year is done.”

The number of doctors participating in MIPS is another key factor affecting the size of bonuses and penalties. “Different medical fields may be rooting for more or fewer exclusions from participation in MIPS in future

4 How is MIPS affecting reimbursements for the cost of Part-B drugs?

Dr. Repka says that, contrary to what some thought might happen, MIPS penalties and bonuses will not be applied to the reimbursement of part-B drugs, a factor that could have profoundly impacted doctors such as retina specialists. “The reimbursement of part-B drugs is excluded right now from the application of the bonus and penalties,” he explains. “In last year’s guidelines, and in this year’s proposed rule, it’s been made clear that reimbursement of the practice for part-B drugs will not be affected by the penalty or bonus.

“Suppose you had a 5-percent penalty, and it included your part-B drug costs,” he continues. “That would mean you were underwater before you even paid to have the drugs shipped to you. That expense for the part-B drugs used by the patient is included in the ‘cost’ category of MIPS, but that metric is only 10 percent this year, so it’s still a very low number. Of course, if that category increases, the impact of part-B drug selection attributed to the retina surgeon could have serious negative effects, so we need to watch carefully as CMS rolls out these changes, and we have to continue to object to some of their methodologies for allocating expenses.”

5 What is the alternate payment model, and how might it help me?

Dr. McClellan explains that within MACRA, the overall system that created the MIPS program, there are two big tracks that physicians can follow. “In MIPS you report on a set of measures relating to

“These models are generally not available to ophthalmologists,” he continues. “That’s a concern for me because it means that ophthalmologists don’t have as much opportunity to access the advantages of the APM model. Those advantages include not only the opportunity to get support for delivering care in ways that are potentially better or more efficient

“Probably the only way ophthalmologists can participate in the APM model is if they’re part of a large health-care organization that’s become a Medicare accountable-care organization,” he says. “In an ACO, all of the providers agree to be paid based on overall costs and some population-oriented outcome measures relating to the Medicare patients they primarily take care of. This works well for primary-care physicians and some specialists, such as those caring for diabetes or heart-disease patients. In those cases, there are some performance measures and relatively straightforward ways for them to coordinate care better with the primary-care doctors in the organization. But the kind of care provided by ophthalmologists, which typically involves discrete services like cataract surgery or macular-degeneration treatment, is harder to fit into that structure. Instead, we need APMs that focus on supporting ophthalmologists who treat these specialized problems better or at a lower cost.”

Mr. Grant adds that some doctors consider having an ACO manage the reporting to be a significant benefit. “I haven’t seen many doctors say that this is the only reason they’re signing a contract with an ACO—so that they’ll handle the MIPS reporting,” he says. “But some have told me it was a major part of their decision to sign.”

6 What is attribution, and why is it problematic?

“One problem that unfairly affected ophthalmologists in the past—especially retina specialists—is a thing called attribution,” Mr. Grant explains. “This was part of a cost-related component in the reporting. Patients were ‘attributed’ to a particular doctor, based on factors such as how frequently the doctor was seeing the patient and whether the doctor was billing using evaluation and management, or E&M, codes. If you saw a patient often and used those codes—which retina specialists often do—then any Medicare charges associated with that patient were attributed to that doctor, even if they were totally unrelated to what the doctor was treating. For example, a retina patient might go to the hospital and have $20,000 worth of gastrointestinal surgery. Under this system, this cost was attributed to the retina specialist. One of the unintended consequences of this was to make doctors hesitate to treat patients with more serious health issues, knowing that they could get hurt financially as a result.

“This problem was identified about three years ago,” he continues. “It came from an aspect of the old quality program called the value-based modifier. The new cost program has attempted to fix that, and it has, to some extent.

“I don’t believe that CMS wanted to cause doctors to push away patients with more severe problems,” he adds. “I’m sure these were unintended consequences. In any case, under the new MIPS system, last year cost was not even included in the bonus/penalty system. This is the first year it’s been included, and for now, it’s a small percentage of MIPS reporting. We’ll see how that plays out as things unfold in the future.”

7 How will “Physician Compare” impact my practice?

One controversial part of the MIPS program is “Physician Compare,” which will publish online the measures that doctors report, theoretically helping potential patients to choose the best doctor. “Making quality measures available to the public has definitely produced mixed results,” notes Dr. McClellan. “One major finding is that not many people actually look at the measures that are posted. That may be partly because it’s inconvenient for people to spend the time and effort to find them

“Right now, MIPS measures are focused on treatment processes and safety issues,” he continues. “Obviously these things are important, but they’re not things that most patients think about when they’re choosing a doctor. If we move more toward measures relating to functional outcomes, more attention might be paid to the postings. Right now, that’s not what the MIPS measures are focused on. So even though doctors may be unhappy if they come out looking less capable or patient-friendly than their competitors, the reality is that the measures that are available online now probably won’t generate an enormous amount of public attention.”

8 Is a small practice at a disadvantage?

“Those in small ophthalmology practices and those who don’t have an EHR system are likely having a harder time participating in MIPS successfully,” says Dr. Repka. “However, this probably represents a small number of practices, and those practices have had some straightforward ways to avoid a penalty and remain neutral in terms of reimbursement. In 2017 measurements, you only had to accumulate three points to avoid a penalty. This year it’s still easy to avoid the penalty with a few steps, which will be reflected in

Mr. Grant says he doesn’t believe a small practice will have a harder time managing MIPS than a large practice. “If it’s a one-doctor practice, the doctor probably has a tech or two, and they’ll have to change some of their habits,” he says. “The doctor and staff at the front desk will have to do a few things differently. But that’s equally true for a practice with 10 doctors and 20 techs. In addition, CMS thought that small practices might have a harder time managing the data, so this year they gave them some bonus points for being small. That’s not a huge thing, but it’s a help, and it shows that CMS is trying to come up with ways to help out.”

9 What about the possibility of opting out of MIPS?

Mr. Grant says some practices are opting out of the system—at least for now—for several reasons. “Some practices have a very low Medicare volume,” he points out. “They may calculate that the cost of having staff take the time to handle the data and do the reporting will be greater than the bonus they’ll receive for doing it, especially if they don’t have EHR and can’t use IRIS. They might say, ‘I’m going to spend $20,000 to save $20,000, or maybe only to save $10,000. It’s not worth it.’ On the other hand, the penalties for opting out will keep increasing, eventually reaching 9 percent. If a practice has a million dollars in Medicare payments, that would be $90,000 in penalties. I suspect it would be worthwhile to hire somebody to do the manual work to prevent the penalty at that point. So I think you’ll see practices shifting their strategies as the penalty level goes up in the next few years.”

10 Is MIPS likely to actually accomplish something positive?

Clearly, a system such as MIPS springs from good intentions, but whether it will end up having a positive impact is a different question. Among surgeons’ concerns is the possibility that because of MIPS, doctors will avoid seeing patients as often as they should, or will refuse to treat more challenging patients to avoid being financially penalized.

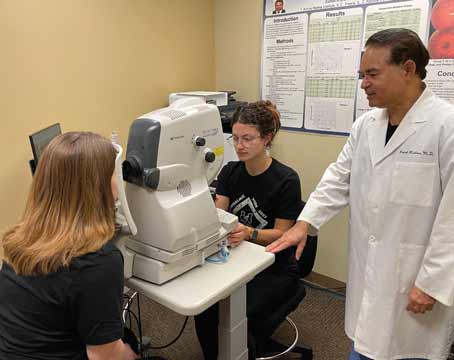

|

“Causing surgeons to avoid treating high-risk patients, such as patients needing a very difficult retina-reattachment procedure that costs a lot and involves a lot of disposables, is a real risk any time you base reimbursements on outcome measures—if the system cannot accurately risk-adjust,” says Dr. Repka. “The system is definitely moving toward outcome measures, such as what percentage of cataract surgery patients see 20/25 or better. The folks at CMS keep saying they know how to risk-adjust and compensate for this.

“At the moment, we’re not sure they can do that very well,” he continues. “In fact, we’re pretty sure they can’t do it well. So yes, the ability of CMS to risk-adjust is a concern, because we don’t want to penalize surgeons who are providing care to patients with more serious problems. And we do not agree that what CMS is doing at present is adequate. I think they’re trying to get this right, but I don’t think they’ve been completely successful so far.”

“To do well in this system,” notes Mr. Grant, “you’ll have to learn to do only what you can justify and defend in your documentation. If you need to see a patient every week for three weeks, and that’s clinically supported by other doctors and your professional society, then do it. CMS, however, decided that there were doctors seeing patients for visits that were not truly

“I have no problem with trying to make doctors more mindful about that,” he adds. “I’m a taxpayer, and I think the program needs to be run in an efficient way. But I don’t want a doctor to not do something that’s clinically relevant because he’s concerned about having his hand slapped. Unfortunately, a system like this does have that potential.”

Even if the system has a positive impact, is it worth participating in from the doctor’s perspective? Dr. Repka says it depends how you look at it. “Some of the money doctors are forced to spend to participate successfully may really be contributing to improved quality of care,” he points out. “Being able to benchmark and evaluate your practice, to look for outliers in performance and do these assessments quickly, is probably a real quality-improvement tool, as well as a potential money saver for the health-care system. On the other hand, if you see this as an extra cost of doing business and think that you may not get back as much as you’re putting in, you’re also probably right. And exactly how much of the spending is really contributing to improved quality of care is unknown.

“My view,” he concludes, “is that this is a program the AAO is trying to modify so that Academy members don’t lose more than is necessary, and so the vast majority can succeed and be eligible for the bonus payments.”

11 What is CMS doing to improve MIPS?

As doctors well know, the best-intentioned programs are often flawed, and MIPS is no exception. So a key concern is how CMS is working to uncover and correct issues that are causing unintended problems.

Mr. Grant says that one positive thing CMS has done is eliminate some pointless documentation requirements. “When meaningful use first came out, there’s no question that it required doctors—especially specialists—to do things that were a bit silly,” he says. “Some of the documentation requirements just didn’t make sense. They were asking for minutiae that had nothing to do with the bigger picture.

“The current, first version of MIPS is far better than what doctors were dealing with before,” he continues. “Most of what’s required now makes more sense. Furthermore, CMS has made it about as easy as possible for a practice to avoid a penalty; for now, the requirements are very low. If you do just a couple of very nominal things, your practice ought to be able to avoid a penalty. If you want to get into this slowly, you can. If you want to go all-in and do everything you can to get the maximum incentive right from the start, you can do that, too.”

Dr. McClellan notes that one of the challenges going forward will be to see if CMS can develop new kinds of payment approaches that could offer the same advantages to ophthalmologists that doctors in the APM models receive, helping to improve care and lower the total costs of treating specialized health problems while getting ophthalmologists paid better for doing so. “CMS is working on this,” he says. “Medicare has a center within CMS called the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation that focuses on developing new payment models,” he explains. “To my knowledge, none of the current payment models is really focused on common ophthalmologic conditions, even though this is a big part of Medicare spending. Maybe that’s because things are going relatively well in terms of payment rates and quality-of-care access. This is a challenge for the clinical leaders in ophthalmology: Given the way that Medicare pays, is there a different payment approach that could be better aligned with getting good ophthalmologic outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries at a lower total cost of care? Ophthalmologists would know best about that.

“What’s notable is that MIPS doesn’t reward physicians for minimizing other types of spending,” he continues. “Some of the major costs to the system come from physician decisions about things such as where a procedure is performed. The same procedure might be performed in a hospital outpatient department at a higher cost than in a physician’s office, with similar—or possibly even greater—quality if it were done in the office. But under MIPS there’s no real reward for physicians to take steps to get those costs down. Many of the APM models do take this into account, rewarding physicians for decisions that lower overall costs, but again, the current APM models aren’t really designed for ophthalmologists.

“For example,” he says, “the Innovation Center has developed a new payment model for oncologists that allows them to manage their cancer patients with team-based approaches to care, and more patient engagement, avoiding some of the costly complications from cancer treatment such as urgent hospital admissions. At the same time, those savings in hospital and other costs enable the practices to get paid significantly more. That, in turn, allows them to spend more money on resources that can help patients and prevent other complications. This model rewards them for finding less-costly drug treatments and other interventions, and it provides an additional payment opportunity that gets them out of the usual MIPS reporting requirements.

“What generally helps to move these alternate models forward is both sides working together,” he adds. “That means that leaders in the clinical community can help by proposing ideas for how care could be improved and better supported with alternatives to fee-for-service payments. If ophthalmologists aren’t happy with current MIPS programs, or if they want to have access to the additional payment bonuses that go along with the APMs, they need to help come up with new ideas and approaches to help make that a reality.”

Dr. McClellan notes that in general, using measures to differentiate

Mr. Grant notes that despite the improvements that have been made, many doctors still feel they have reason to complain. “You can’t please everyone,” he says. “But I believe CMS is listening, and I think MIPS is evidence that CMS is trying to make the program better and less onerous for providers, while still getting valid data out of it and trying to encourage habits that are reasonable. We’ll see how it works out as they continue to tweak the system.”

12 What’s likely to happen in the years ahead?

“Doctors have been aware of the shift toward more paperwork, scrutiny

“The challenge for the medical profession is, what do you want that transparency to be about?” he continues. “Are the MIPS measures the right measures? Are they measuring things that actually matter to patients? Are they measuring things that doctors really care about improving? Today, MIPS measures don’t necessarily fit that description—they’re more about the processes of care or features of the doctor’s EHR capabilities. They’re not really measuring the things that matter most to patients.

“The initial implementation of MIPS hasn’t caused major disruptions in care, and some of the steps taken by CMS to reduce the measurement burden and help physicians manage this

Dr. Repka says he’s hopeful for the future, despite the challenges. “In general, ophthalmology is likely to be a big winner in this program compared to other specialties, for a lot of reasons, some of which are inherent to ophthalmology,” he says. “Ophthalmologists tend to be interested in technology and electronics, and a large percentage of practices were early adopters of EHR. On top of that, the IRIS registry has pooled the data together to make the effort fairly seamless, so you don’t have to pay an employee to enter the data. Of course, it’s possible to do that manually, but it’s much more cumbersome.

“It’s very reasonable for a payer to assess the services physicians provide for their insured,” he continues. “A payer has that right. We know

“No one is ever going to say, ‘I love MIPS!’ ” adds Mr. Grant. “However, after practices start to receive substantial bonuses, they may not feel that the system is unreasonable. We’ll see what happens one the incentives and penalties begin to appear.” REVIEW

Dr. Repka consults on this topic for the