Have you noticed an increase in consults for newborn eye screening exams with syphilis exposure recently? I’ve seen a significant rise in my practice over the past 12 to 24 months. Why is this happening, and how should pediatric ophthalmologists approach these patients? This article will discuss the recommended frequency and timing of eye screenings in newborns with syphilis exposure, as well as the specific systemic and ocular signs to be aware of.

Resurgence and Rise of Congenital Syphilis Cases

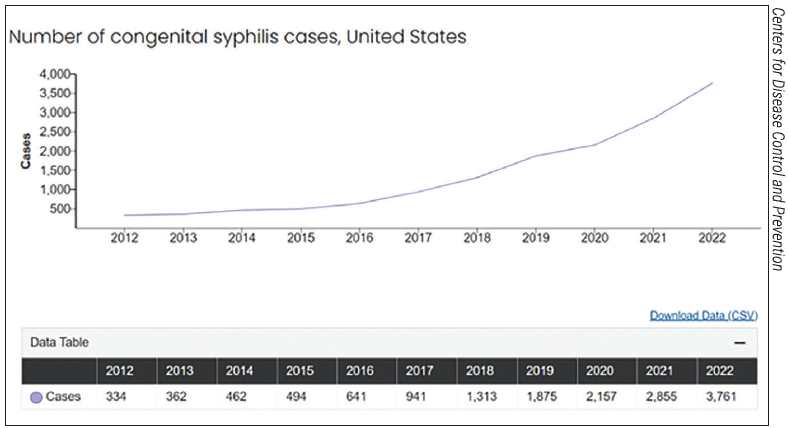

Despite national efforts to raise awareness and control the spread of syphilis, the incidence of congenital cases has been on the rise, with a reported 219.3-percent increase between 2017 and 2021, in contrast to other sexually transmitted infections such as chlamydia or gonorrhea, which have been stable or declining.1 These numbers are especially worrisome considering data from 2022, which shows a nearly tenfold increase from the 335 cases of babies born with syphilis in 2012.2

The significant rise in congenital syphilis cases deeply concerns health-care leaders. Jonathan Mermin, the director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention, stated, “The congenital syphilis epidemic is an unacceptable American crisis. All pregnant mothers—regardless of who they are or where they live—deserve access to care that protects them and their babies from preventable disease.” Between 2016 and 2023, annual reports of congenital syphilis ranged from 700,000 to 1.5 million cases worldwide, and 2,677 cases were reported in the United States in 2021 alone (Figure 1).1,2

|

|

Figure 1. The number of congenital syphilis cases in the United States from 2010 to 2020.19 |

Despite the severe symptoms and poor outcomes in untreated infants and children, there’s hope to combat the congenital syphilis epidemic. This hope stems from findings that timely testing and treatment could prevent nine out of 10 congenital syphilis cases. More than half of the current patient population testing positive for syphilis struggles with receiving adequate care. Nearly 40 percent of those are women without prenatal care, which means that there are definitive ways to improve outcomes.2

Understanding At-Risk Groups

Effective prenatal screening and antibiotic treatment can prevent congenital syphilis; therefore, the risk of infection is highest among groups with significant barriers to accessing health care. Women with lower socioeconomic status often experience prolonged delays in prenatal care due to lack of transportation, difficulties navigating Medicaid, and insufficient knowledge of screening protocols.3 These barriers are particularly relevant to women with histories of substance abuse and housing insecurity who may avoid care altogether due to societal stigma or potential legal consequences. Vulnerable populations also include non-English speakers and women with low levels of education, as they often lack knowledge regarding safe sex practices and how sexually transmitted infections may impact pregnancy.4,5

Pediatric Ocular Findings What ocular findings should a pediatric ophthalmologist look for when examining a neonate for eye involvement in syphilis?

|

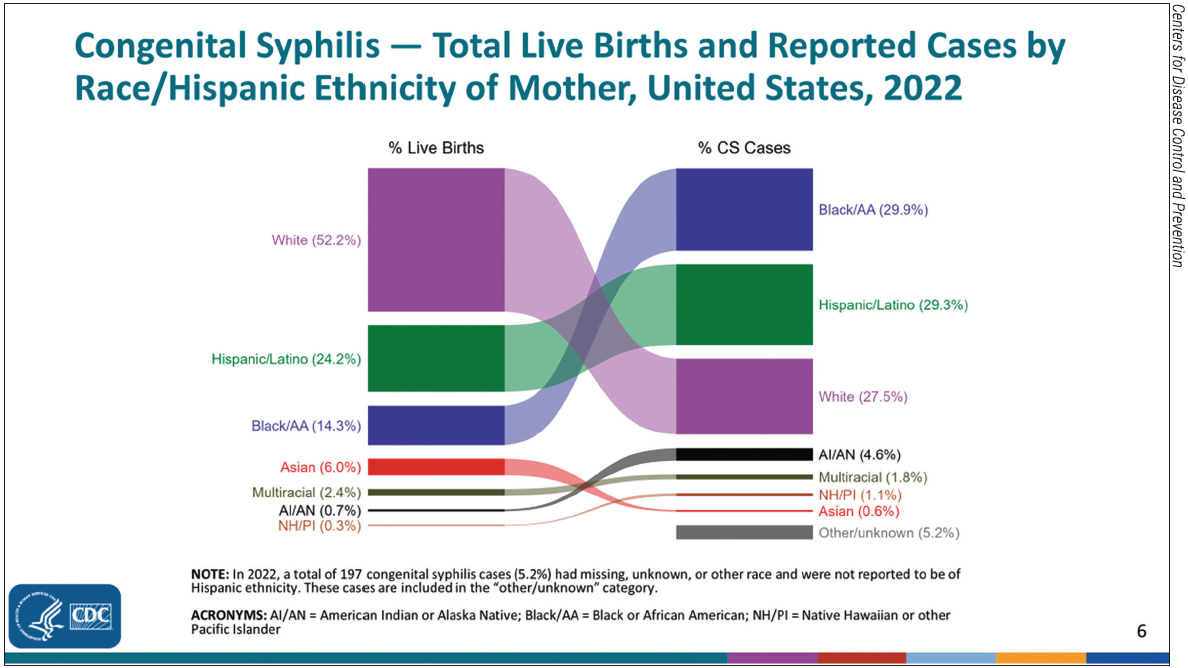

While all racial groups are experiencing increased rates of congenital syphilis, the burden of infection disproportionately affects racial minorities who already face inequities in health-care access. American Indian/Alaska Native populations are acutely affected by congenital syphilis—despite making up only 0.7 percent of live births, these infants account for 4.6 percent of reported congenital syphilis cases.6 While the total number of reported cases remains small (171 in 2022), rates of congenital syphilis among AI/AN births surged between 2018 and 2022, rising from 101.8 to 644.7 cases per 100,000 live births (Figure 2).7 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Latino and Black communities are also experiencing high rates of congenital syphilis, with infants born to Black mothers composing the most significant total number of reported cases by race.7 Despite 30 percent of all infections occurring in White-mother births, rates of reported cases for this group remain well below that of communities of color, increasing to 54.1 cases per 100,000 births in 2022.8

The geographic distribution of U.S. congenital syphilis cases is concentrated in the South and West. This trend reflects the nation’s demographic and inter-state differences in health-care infrastructure. The five states with the highest rates of congenital syphilis (NM, SD, AZ, TX, OK) possess significant American Indian populations, with the next five states similarly being home to large populations of other at-risk racial groups.7,9 Regions most affected by rising cases also lack the maternal health infrastructure needed for effective prevention and treatment. Many of the states ranking within the top half for congenital syphilis rates suffer from large “maternity care deserts,” areas of the state lacking a combination of obstetrics care, adequate providers, and birthing facilities.7,10 Rural and low-income urban communities often fall under the definition of maternal care deserts, thereby lacking the prenatal screening services required to prevent syphilis cases.

|

|

Figure 2. The number of total live births and reported cases of congenital syphilis in the United States by race/Hispanic ethnicity by mother in 2022.20 |

Screening and Diagnostic Methods

The indiscriminate nature and unpredictable timing of maternal syphilis transmissions create a vulnerability for children at any point during pregnancy and childbirth. Given the current understanding of the different risk groups involved, what modalities and signs should medical professionals incorporate into their practice to screen for congenital syphilis?

The medical checklist recommended for screening signs and symptoms associated with congenital syphilis includes:

1. Nose. Rhinitis with mucopurulent nasal discharge.

2. Skin. Jaundice, rash, and desquamation.

3. Abdomen. Abdominal pain or tenderness due to peritonitis or hepatosplenomegaly.

4. Eyes. Vision impairment or any form of ocular inflammation.

5. Other. Pseudoparalysis of an extremity due to osteochondritis.

Alongside these general examinations, a thorough maternal medical history and pregnancy history should be obtained, as the quality of a comprehensive medical history may isolate important risk factors and significantly determine diagnostic outcomes.

The presence of syphilis is diagnosed by the collection of maternal and neonatal blood samples to undergo laboratory testing for rapid plasma reagin (RPR), venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) levels, blood count, and signs of thrombocytopenia in the neonate. CSF reactivity for VDRL, elevated CSF cell count, and fluorescent antibody detection for Treponema pallidum may be used to further diagnose syphilis. Positive tests may also be obtained from darkfield tests or PCR of the placenta, cord, any lesions, and/or body fluids from the neonate. Obtaining photographs of congenital anomalies is important for record-keeping and prognosis of long-term complications.8

Any abnormal physical findings associated with the symptoms described in the diagnostic methods or serum quantitative titer higher than the maternal titer at delivery by fourfold values would categorize the neonate into a highly probable case of congenital syphilis. In this case, a complete CSF analysis with values on VDRL, cell count, and proteins, along with CBC, long-bone radiographs, and other relevant clinical testing—ophthalmologic examination, liver function test, and neuroimaging—is recommended.11

The same evaluation methods—complete CSF analysis, CBC, differential, platelet count, and long-bone radiograph—are recommended for neonates with normal physical examination and less than a fourfold difference in nontreponemal quantitative titer from the maternal titer, but with a mother who was inadequately treated or not treated at all.

Systemic and Ocular Manifestations

One of the biggest challenges presented with the congenital syphilis epidemic is the difficulty in early recognition of symptoms. Laboratory values and antibody testing are reliable metrics for diagnosis. Still, there are risks of long-term complications and medical oversight for situations in which mothers test negative for syphilis during the 16-week gestational period. There’s been evidence of congenital syphilis transmission in countries with high rates of antenatal screening due to medical providers’ reliance on lab values.12 There are only general indications and broad symptoms linked to congenital syphilis, but any abnormalities in physical exam findings or reasons for suspicion during medical history should prompt a heightened awareness for a differential diagnosis to improve the rate of early recognition and prevention of further complications.

Congenital syphilis arises from transplacental transmission of Treponema pallidum from an infected mother to a fetus. Infants coming into direct contact with a syphilis sore during the postpartum period can also present with systemic clinical manifestations of jaundice, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, long-term disabilities, and central nervous infections often observed in congenital syphilis cases.1,13

|

|

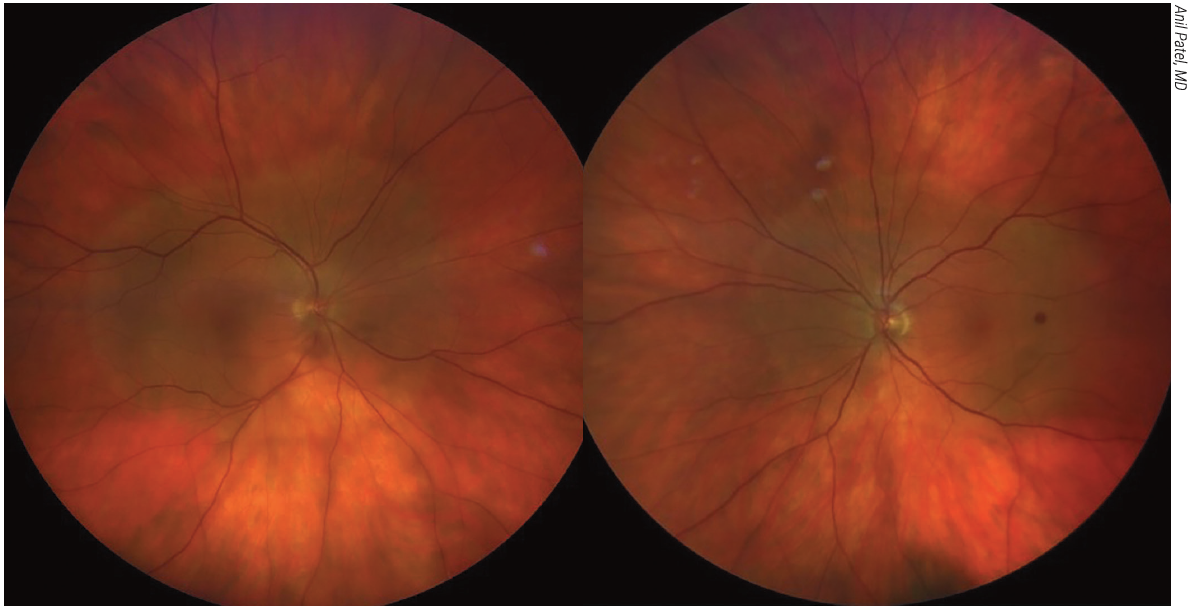

Figure 3. Fundus photographs showing acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. |

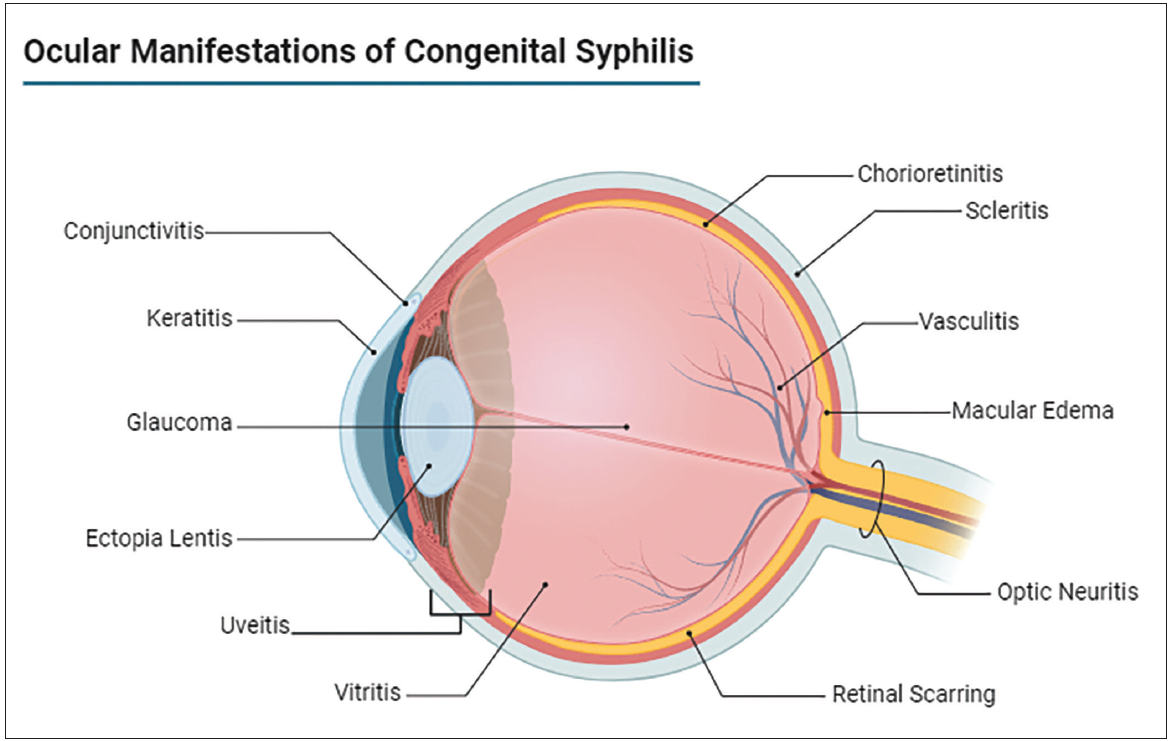

Many ocular structures can be affected by syphilis infections, with findings extending from the front to the back of the eye. Anterior segment findings include keratitis, unilateral or bilateral iritis with granulomatous features, and secondary glaucoma. Patients may have chorioretinitis, vitritis, vasculitis, macular edema, and optic neuritis in the posterior segment. Inflammation can cause damage to these structures and lead to retinal and corneal scarring and optic atrophy.12,13 In cases of untreated congenital syphilis, bilateral interstitial keratitis is one of the most recognized and diagnosed presentations, presenting as early as two-year-old patients but more commonly observed in the age range of 5 to 15 years. Hutchinson’s triad, which consists of interstitial keratitis, notched incisors, and sensorineural hearing loss, is a hallmark set of symptoms in children with congenital syphilis. These children can also manifest other features such as saddle nose deformity, ectopia lentis, conjunctivitis, and scleritis.

|

|

Figure 4. Fundus photograph showing syphilitic optic neuritis. |

Treatment

The recommended treatment regimen for systemic syphilis infection involves an administration of aqueous crystalline penicillin G (100,000-150,000 units/kg body weight/day administered as 50,000 units/kg body weight/day) by IV every 12 hours during the first seven days of life and every eight hours after that for 10 days or Procaine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight/day IM once single dose for 10 days. Benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight/day IM once single dose for 10 days can be administered for neonates with possible or less likely congenital syphilis.14 Infants who experience allergic reactions may undergo desensitization treatment before the penicillin G regimen. Due to its efficacy and widespread availability, penicillin G is administered in most congenital syphilis cases. Ceftriaxone can be considered in the event of penicillin shortage with expert consultation and serologic testing.

In addition to penicillin, the ophthalmic manifestations of congenital syphilis may require additional treatment. Topical steroids may be used for the treatment of interstitial keratitis; however, their use for uveitis and scleritis isn’t currently recommended by the CDC, as there’s no demonstrated evidence of benefit.7 The role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is also unclear in patients with other types of severe ocular inflammation or macular edema. Surgical procedures may be necessary to manage rare cases of cataracts and secondary glaucoma due to ocular inflammation. As always, pediatric ophthalmologists should look to correct any refractive errors and treat possible amblyopia.

Mitigating Spread and Increasing Detection

Penicillin is an effective method of treating congenital syphilis once the diagnosis has already been confirmed; however, any meaningful reduction in overall rates will require increased prevention of syphilis before it can infect the fetus. A vast majority of congenital syphilis cases are a partial result of inadequate screening and treatment of the birth mother during pregnancy.15 Test timing and regularity are crucial—a greater frequency of screenings throughout pregnancy increases the likelihood of identifying late-presenting instances of infection. Sufficient prenatal testing and treatment will significantly reduce overall congenital infection while also narrowing gaps that exist between geographic and racial groups.16,20

The absence of characteristic symptoms in latent infection further complicates the diagnosis of congenital syphilis. In the context of ocular manifestations, T. pallidum spirochetes may persist in the aqueous fluid and lens cortex, and while rare, the infection may remain asymptomatic until reactivated to invade surrounding structures such as the cornea, uvea and retina.17 Latency may persist for decades, with some patients unaware of congenital infection until cataract surgery results in postoperative inflammation of the anterior eye.16,18 Therefore, ophthalmologists should always keep an eye out for various social risk factors associated with congenital syphilis, including maternal sexual history in the at-risk demographic.

|

|

Figure 5. Ocular manifestations of congenital syphilis. Created with BioRender Software. |

Ophthalmologists can help curb the growing trends of congenital syphilis in their everyday practice by communicating findings to pediatricians, related specialists and public health agencies. Notifying the patient’s pediatrician is especially critical in the treatment process, allowing for the coordination of a multi-specialty team to address the systemic sequela of congenital syphilis infection.

The Takeaway

Syphilis rates have rapidly risen over the last five years. Congenital syphilis rates are significantly elevated in comparison to other stable or declining sexually transmitted infections. Congenital syphilis is most prevalent in the southern and western United States, particularly among Indigenous, Latino and Black populations.

Comprehensive physical exams and a detailed history should be obtained for all infants with suspected maternal history of syphilis infection, as standard antibody tests may not detect infection during the gestational period. If suspicion of congenital syphilis is high, perform ocular exams to evaluate for the following: chorioretinitis and pigmentary chorioretinopathy (“salt and pepper type”); congenital syphilitic keratouveitis; secondary glaucoma; cataracts, interstitial keratitis; and optic neuritis/atrophy.

Penicillin G (50,000 units/kg body weight/day) is the principal treatment for congenital syphilis. Dosing is determined based on the likelihood of syphilis infection; however, the most effective method of combating congenital syphilis rates remains preventative screening during pregnancy.

Mr. Park and Mr. Nguyen are medical students at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine.

Dr. Yanovitch is a clinical professor and director of medical student education at the Dean A. McGee Eye Institute in Oklahoma City. They have no related financial disclosures.

Correspondence:

Tammy Yanovitch, MD, MHSc

608 Stanton L. Young Boulevard

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Phone: 405-271-1094

Email: tammy-yanovitch@dmei.org

1. Wang X, Liao L, Yang X, et al. Ocular syphilis: A comprehensive review. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2022:11:5:547.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Newborn syphilis cases increase, and public health officials urge awareness. 2023.

3. Salinas J, Day J, Ochoa R, et al. The role of screening for congenital syphilis in prenatal care. BMC Public Health 2020:20:789.

4. Pardo M, Schmitz M, Pizones J, et al. Trends in congenital syphilis and implications for prevention. Pediatr Res 2022:92:3:496-502.

5. Zhang Y, Wang Q, Zhang L, et al. Syphilis epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Pathogens 2022:11:5:547.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 STD Surveillance Report. 2023.

7. Koundanya VV and Tripathy K. Syphilis ocular manifestations. StatPearls. Updated August 25, 2023.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quick reference handbook for congenital syphilis surveillance.

9. Administration for Children and Families. American Indians and Alaska Natives: Numbers and demographics. 2023.

10. Miller S, Dempsey A, Darrow A. The effect of National Health Service Corps on health outcomes. Med Care 2021:59:10:893-900.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment guidelines for congenital syphilis.

12. Taha T, Al-Mahfoudh R, Abbas A, et al. Epidemiology of syphilis and its implications for treatment. Lancet Infect Dis 2020:20:4:450-458.

13. Kankam H, Bafor A, Arhin S, et al. Increasing trends in congenital syphilis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022:22:104.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment guidelines for congenital syphilis.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR: Congenital syphilis in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023:72:46:e1-e4.

16. Whittington J, Churilla A. Syphilis diagnosis and treatment in adults. J Am Board Fam Med 2008:21:3:185-192.

17. Johnson L, Mckelvey K. Epidemiology of congenital syphilis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992:11:4:343-347.

18. Paik J, Yoon S, Kim J, et al. The role of molecular methods in diagnosing congenital syphilis. BMC Ophthalmol 2023:23:212.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effects of HIV, STDs, TB, and hepatitis on pregnancy. Accessed September 19, 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy-hiv-std-tb-hepatitis/effects/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/pregnancy/effects/syphilis.html.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD surveillance 2022: Figure 1. Accessed September 19, 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/figures/disp-1.htm.