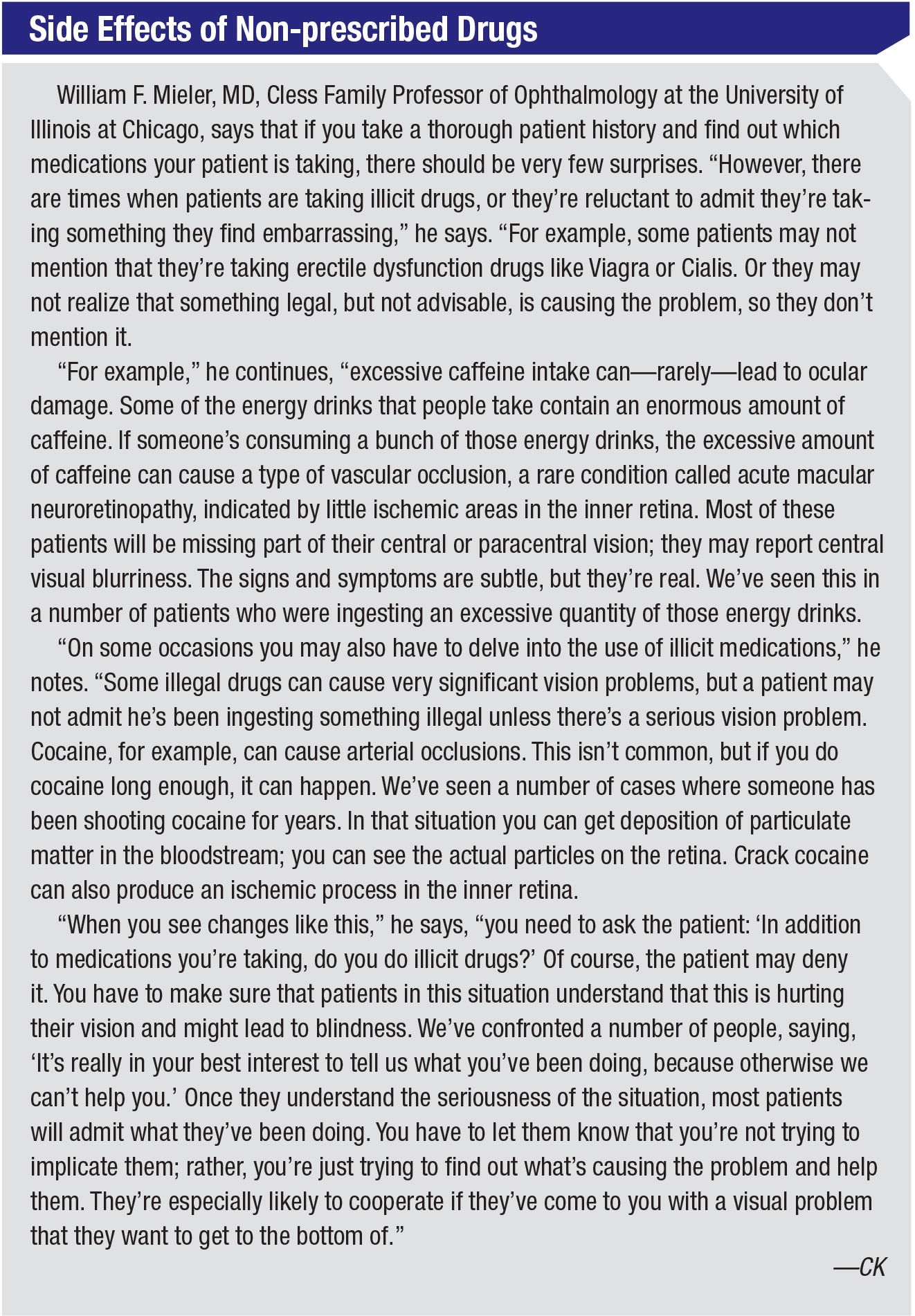

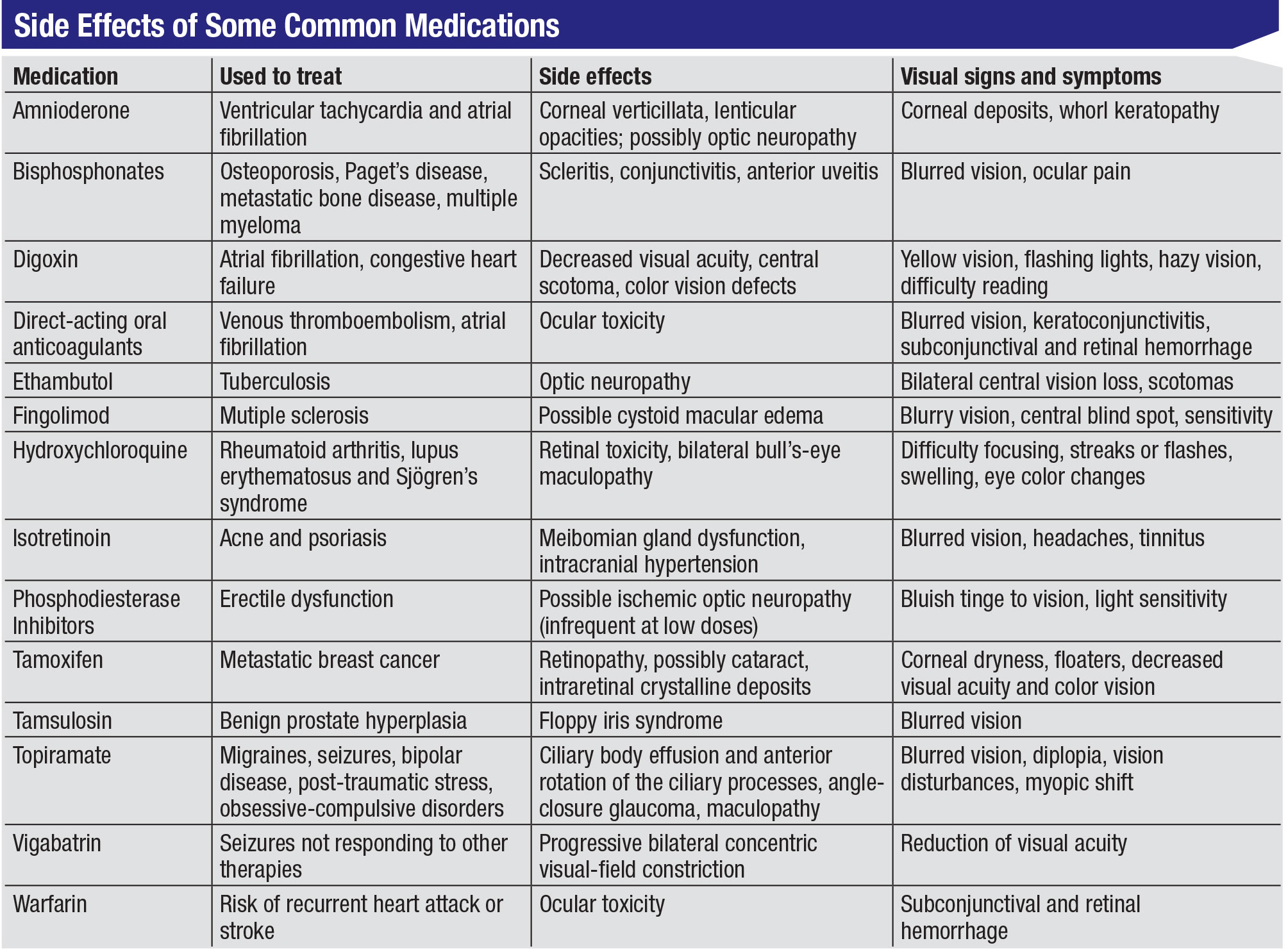

As every ophthalmologist knows, diagnosing ocular disease can be a challenge. One reason it’s not always easy to nail the diagnosis is that patients are often being treated for other health concerns with drugs that can have ocular side effects.

“A variety of systemic medications cause ocular side effects,” says Eric D. Donnenfeld, MD, an anterior segment specialist and clinical professor of ophthalmology at New York University Medical Center and a partner at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island. “Those side effects are real, and they’re commonly underdiagnosed.”

|

“Ocular side effects are much more common than you might expect,” notes William F. Mieler, MD, Cless Family Professor of Ophthalmology and vice-chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Even ophthalmologists with a general practice will probably encounter an ocular side effect of a systemic medication once a week or so; which ones you encounter will depend partly on your practice. For example, in addition to seeing retina patients, I work in oncology, so I see numerous complications caused by cancer treatment medications. As you might imagine, those can be quite damaging.”

Here, doctors with expertise in the ocular side effects of systemic medications share their experience with some of the drugs most often associated with ocular problems, and offer advice on how to proceed when you encounter them.

The Front of the Eye

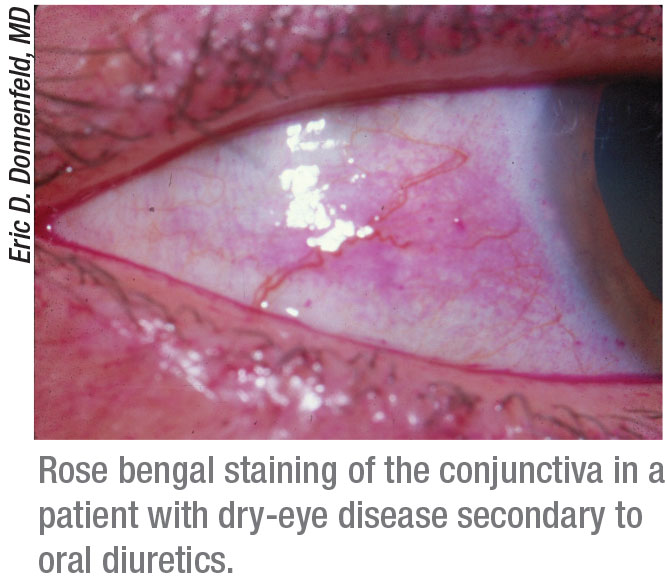

Many systemic drugs are associated with dry-eye-related signs and symptoms, conjunctivitis and corneal problems.

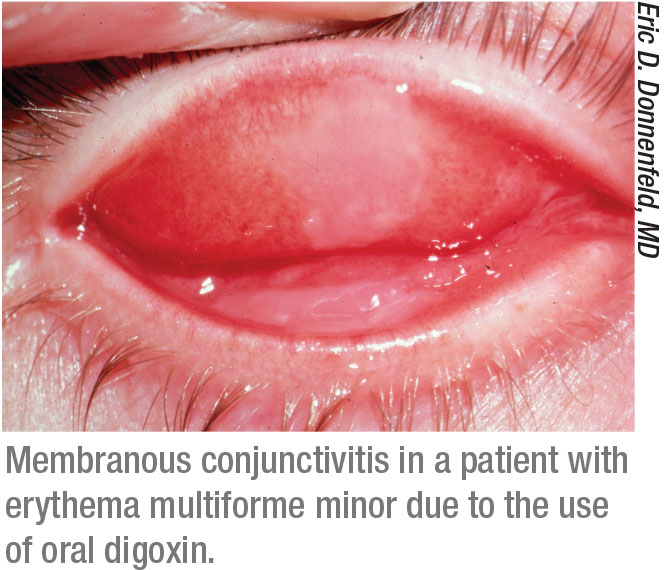

• Oral diuretics. “A recent development that’s been associated with ocular surface problems is a change in the primary therapy used to address high blood pressure,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “In the past, medications such as ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers were used as primary therapy for these patients. Now, the primary therapy is the use of oral diuretics. Oral diuretics have significant dry-eye side effects and also have been reported to contribute to open-angle glaucoma.”

• Biologics. “A new medication called dupilumab [Dupixent, Regeneron], prescribed by dermatologists to treat atopic dermatitis, has been reported to cause conjunctivitis in about 20 percent of treated patients,” says Stephen C. Pflugfelder, MD, a professor and director of the Ocular Surface Center at Baylor College of Medicine’s Cullen Eye Institute in

Houston. “Ironically, atopic dermatitis, an inflammatory skin condition, is itself associated with ocular comorbidities such as blepharitis, glaucoma, cataracts, retinal detachment and keratoconus, among other issues.

“Dupilumab is the first biologic treatment for atopic dermatitis,” he explains. “In one study, dupilumab treatment was associated with a 5- to 28-percent increase in the incidence of conjunctivitis, compared to patients treated with placebo.1 One case series found that 70 percent of patients treated with dupilumab developed anterior conjunctivitis.2 Symptoms noted included burning, tearing and a decrease in visual acuity; signs included hyperemia of the limbus and conjunctiva.

“Options for managing these signs and symptoms include stopping the use of dupilumab, if the complications are severe,” he adds. “If the dermatologist doesn’t consider that a good option, some success has been reported treating with a topical steroid such as fluorometholone; tacrolimus ointment; or lifitegrast, if the patient doesn’t tolerate the topical steroids.”1,3

• Anticholinergics. Dr. Donnenfeld notes that these drugs may cause dry-eye symptoms. “The use of anticholinergics is very common,” he points out. “Among other things, they’re used to treat Parkinson’s disease and used as stomach relaxants and anti-anxiety medications. They often cause significant dry-eye-related side effects that can’t be addressed effectively with topical medications. Many times we have to go back to the internists and surgeons prescribing these medications and ask them to alter the treatment.”

• Antihistamines. Dr. Donnenfeld notes that antihistamines such as Benadryl, commonly used to treat allergies, can trigger dry-eye symptoms.

• Amnioderone. “Amnioderone is used to treat cardiac arrhythmias,” Dr. Donnenfeld explains. “It can cause a whorl dystrophy of the corneal epithelium called vortex keratopathy that can decrease visual acuity. If the patient can’t be taken off this therapy, the epithelium can be debrided to remove the offending whorl dystrophy.” Dr. Donnenfeld also points out that

amnioderone has been associated with ischemic optic neuropathy in some patients.

• Chemotherapy drugs. “Chemotherapy used to treat cancer will often damage the lacrimal glands, causing dry eye that can last for months,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “Furthermore, many patients receiving therapy for breast cancer are on anti-estrogen medications, and the resulting change in hormonal status can lead to dry eye as well.” (Note: Chemotherapy drugs are powerful, and can cause a range of other ocular complications as well. For more on that, see the bullet point on page 45.)

Retinal Side Effects

Several dozen drugs have been associated with retinal toxicity or abnormalities. Among the drugs often associated with retinal damage are hydroxycholoroquine, thioridazine, bisphosphonates and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors.

• Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil). Retina specialists often encounter patients that have been treated with this medication, frequently prescribed by rheumatologists. “Most lupus patients are treated with hydroxychloroquine, and it’s the main medication rheumatologists use that’s been linked to side effects in the eye,” says Vasileios C. Kyttaris, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School in Boston. “It’s very good for a milder type of lupus, and it’s been shown to improve overall survival rates in lupus patients. Also, it’s one of the few drugs for lupus—if not the only drug—that can be used during pregnancy. In the past we used the anti-malarial drug chloroquine for this purpose, especially for lupus with severe skin disease. But the incidence of maculopathy with that particular medication was quite high, so today we rarely use it.

“Unfortunately, over the years we’ve found that hydroxychloroquine isn’t as safe as we used to think,” he says. “Many lupus patients take hydroxychloroquine for several years, if not for life, and it seems to have a cumulative effect on the retina, causing maculopathy.”

Dr. Kyttaris explains that this realization has caused rheumatologists to change what’s considered a safe dose of the medication. “Prior to 2010, we used to recommend a dose of 6.5 mg per kg of body weight per day as the upper limit for hydroxychloroquine,” he says. “However, it became apparent that this dose was too high for many people. The previous formula made sense for people with an ideal body weight, but a lot of overweight patients ended up being overdosed. So, the recommended dose has been decreased to 5 mg/kg/day. This change affects a lot of people, because about 70 percent of our lupus patients are on this medication.

“So far, it seems that this lower dose is safer,” he notes. “For the first five years, the incidence of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy is now close to zero. Beyond that the risk of retinopathy increases, but it remains rare.”

|

Dr. Kyttaris says that these patients should be examined by an ophthalmologist every year. “We want to make sure there’s no early change in the macula suggestive of hydroxychloroquine toxicity,” he explains. “We’ve found that if you wait for symptoms to appear—for the patient to complain of decreased vision, changes in color perception and so forth—the damage will be done. So the current standard is to have these patients screened once a year. The ophthalmologist checks the fundus, does color vision testing and does OCTs as well, although my understanding is that OCT may produce some false positive results. In fact, we’re not sure if this type of maculopathy translates into clinically observable changes.”

Dr. Mieler says that he sees numerous patients who are taking hydroxychloroquine for arthritic conditions or systemic lupus erythematous. “How we proceed with these patients depends upon how long the patient has been taking hydroxychloroquine, the dosage of the medication, and whether we find any features of toxicity,” he explains. “Michael Marmor, MD, and I, among others, published detailed guidelines for managing this problem back in 2016, on behalf of the American Academy of Ophthalmology.4

“Once you realize that a patient is taking hydroxychloroquine, you monitor for signs of toxicity,” he says. “If there are no features, you keep monitoring. If you do find signs of toxicity, you talk to the prescribing physician and try to stop the medication. That’s key, because once problems arise, you can’t undo the damage. There’s no treatment for the toxicity once it has occurred, and sometimes it gets worse if the patient is left on the medication.”

Dr. Kyttaris notes that there are other treatment options if a patient taking hydroxychloroquine is developing maculopathy. “We may switch the patient to quinacrine, which is an anti-malarial that hasn’t been shown to cause problems with the macula,” he says. “Quinacrine is an older drug, and it’s a compounded formulation, which means we have to get it from a compounding pharmacy. We have issues with insurance covering it, but it can work in this situation. If we can’t use that, we have to use immunosuppressant drugs like azathioprine or low-dose methotrexate to control the disease.”

• Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. “These include erectile dysfunction drugs like sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil (Cialis),” notes Dr. Donnenfeld. “They’ve been associated with ischemic optic neuropathy, and they can cause changes in photoreceptors, resulting in a change in vision that many patients describe as ‘blue vision.’ ”

• Thioridazine. “Another big category is medications used to treat psychiatric disorders,” notes Dr. Mieler. “Thioridazine (Mellaril) can produce a profound toxicity. We see a couple of cases of that every year. That drug can cause significant loss of retinal pigment epithelium and loss of vision.”

• Bisphosphonates. “There have been some unconfirmed reports that bisphosphonates, which we use to treat osteoporosis, have been linked with uveitis,” says Dr. Kyttaris. “Because those reports haven’t been confirmed, we still use these drugs on patients, even those with a history of uveitis. However, we’re aware of the issue.”

• Tetracycline. Drugs in this class include doxycycline, which may be prescribed by ophthalmologists. “I often prescribe doxycycline or tetracycline for patients who have ocular surface disease,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “These drugs are very effective—but they can also cause papilledema and enlarged ventricles. So some of the medications we use in ophthalmology have significant side effects as well.”

Other Ocular Side Effects

Additional drug side effects include cataract, glaucoma, floppy iris syndrome, keratitis, uveitis and alterations of blood flow.

• Tamsulosin. Tamsulosin is a side-effect-prone oral medication that most ophthalmologists are familiar with. “Tamsulosin is used to treat prostate enlargement and urinary flow in men,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “Every ophthalmologist knows that this drug is strongly associated with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, or IFIS. Other medications in the same drug class—alpha-blockers—such as silodosin, alfuzonsin and terazosin, can also cause this problem. The herbal supplement saw palmetto has been associated with this as well. Its use is more common than you might suppose.

|

“An interesting note about the IFIS side effect is that it doesn’t seem to be dose-dependent,” he continues. “A single dose of drug can cause it. In the past, some ophthalmologists have recommended that the medication be stopped prior to surgery, but in my experience, stopping the medication has very little effect. The IFIS doesn’t improve. As a result, once a patient has taken the drug we’re forced to deal with the floppy iris during surgery. We use very aggressive dilation, nonsteroidals and Omidria [Omeros] to improve iris tone and reduce the need for iris hooks and rings.”

• Oral corticosteroids. “As we all know, corticosteroids can raise IOP, but more commonly they lead to cataracts,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “The most common cataract associated with oral corticosteroids is the posterior subcapsular cataract. Stopping the steroid won’t undo whatever damage has been done, but it should stop the progression.”

Dr. Kyttaris notes that corticosteroids, including prednisone and prednisolone, are also used by rheumatologists. “Over the years we’ve limited our use of these drugs because of their side effects,” he says. “In the eye, these drugs are associated with problems in the anterior segment—unlike hydroxychloroquine, which tends to affect the retina. Steroids can increase both the incidence and progression of cataracts, and they can induce glaucoma by increasing intraocular pressure. Of course, steroids can also affect the eye indirectly by inducing or worsening diabetes, which can then cause diabetic retinopathy.

“Unlike the use of hydroxychloroquine, our professional societies haven’t offered any clear-cut recommendations regarding ophthalmologic screenings for patients using steroids,” he adds. “I think a lot of rheumatology patients on steroids don’t necessarily get close pharmacological follow-ups unless they develop problems. That’s something we may need to change in the future.”

Dr. Kyttaris suggests that ophthalmologists keep in mind that most patients being treated for rheumatoid disease are taking steroids, at least intermittently. “It’s certainly possible that some of what you see is a steroid side effect,” he notes. “If you identify this connection, you can make the rheumatologist aware of it. Then we can try to get the patient to as low a steroid dose as possible, or in some cases take the patient off steroids altogether.”

• Immunosuppressive medications. Dr. Kyttaris notes that immunosuppressive medications like methotrexate, azathioprine and leflunomide are routinely used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, and this type of drug has been associated with infectious complications in the eyes. “This can be a problem, especially if the patient has Sjögren’s syndrome, which is very common in rheumatic diseases,” he says. “The combination of dry eyes, primary or secondary Sjögren’s syndrome and the use of an immunosuppressive drug has been linked to infections such as blepharitis in the eye.”

Dr. Kyttaris points out that the situation is confused somewhat by the reality that many rheumatologic diseases can produce ocular effects such as inflammation on their own—perhaps giving the impression that the drug used to treat the disease has caused the problem. “Many ocular problems such as uveitis, and sometimes scleritis and conjunctivitis, are associated with inflammatory rheumatoid diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and

spondyloarthropathy,” he says. “However, we don’t see these effects as often as we used to because we have better treatments for the diseases. If the systemic disease is well-controlled, ocular inflammatory symptoms are also controlled.”

• Chemotherapy agents. In addition to the dry eye mentioned earlier, these drugs can induce a range of ocular complications, including blurred vision; cataract; conjunctivitis; corneal ulcer; extraocular muscle paresis; eye pain; glaucoma; optic nerve disorder; retinal detachment; retinal tear; retinal vascular disorders; uveitis; and vitreous hemorrhage.5

|

Strategies for Success

These strategies will help ensure that drug side effects are correctly identified and addressed:

• Review the patient’s medication usage history carefully. “Taking a systemic drug history is an important part of understanding a patient’s ocular findings,” says Dr. Donnenfeld. “I suspect that medication side effects are most likely to be found in cases of dry eye, and sometimes in glaucoma. I think it all comes down to the nature of the patient’s ocular problem and knowing what other therapies the patient is on—and whether they can be altered.”

• If you’re not sure about a drug association, try stopping the systemic medication—if possible. “If you encounter a sign or symptom and you’re really not sure whether the medication is to blame, stop the medication if you can, and see if the problem goes away,” Dr. Donnenfeld suggests.

• Take special note if the patient is being immunosuppressed. “If an immunosuppressed patient has an active eye infection that’s not responding to measures such as a topical or systemic antibiotic, the ophthalmologist should discuss this with the patient’s rheumatologist,” says Dr. Kyttaris. “It may be possible for the patient to at least get off the immunosuppressor temporarily, so the infection is better dealt with.”

• Be careful when diagnosing hydroxychloroquine toxicity. “It’s important to be sure that the maculopathy is really being caused by the hydroxychloroquine treatment,” says Dr. Kyttaris. “Hydroxychloroquine really helps many of our patients, so we don’t want to stop it if we don’t have to.”

• If a patient isn’t responding to therapy, consider the possibility that a medication may be responsible for the problem. Dr. Donnenfeld notes that it’s easy to overlook the possibility that a problem is actually being caused by a systemic medication. “If you find that a patient isn’t responding to therapy the way you think she should, take another look at her systemic medications,” he says. “You may spot a reason for her problem.”

|

Keeping Your Eyes Open

“The key is to always get a thorough history listing what the patient is taking—legal or illegal,” Dr. Mieler concludes. “As long as you have a good base of knowledge and an index of suspicion, it’s rare that you’ll miss something. You just have to ask the right questions and understand the associations between the medications and the problems you might see.” REVIEW

Drs. Kyttaris, Mieler and Pflugfelder report no financial ties to any product mentioned. Dr. Donnenfeld is a consultant for Omeros.

1. Wollenberg A, Ariens L, Thurau S, et al. Conjunctivitis occurring in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab—clinical characteristics and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1778-1780.e1.

2. Ivert LU, Wahlgren CF, Ivert L, et al. Eye complications during dupilumab treatment for severe atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2019;99:375-378.

3. Zirwas MJ, Wulff K, Beckman K. Lifitegrast add-on treatment or dupilumab-induced ocular surface disease (DIOSD): A novel case report. JAAD Case Rep 2019;5:34-36.

4. Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, et al; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Recommendations on screening for chloro-quine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthal-mology 2016;123:6:1386-94.

5. Liu CY, Francis JH, Pulido JS, et al. Ocular side effects of systemically administered chemotherapy. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ocular-side-effects-of-systemically-administered-chemotherapy. Accessed 17 September 2019.