Secondary lens implantation can remedy a variety of scenarios, from the wrong power lens having been implanted to a lens that’s creating problems within the eye such as UGH syndrome or one that’s decentered or dislocated. However, the ideal place for a lens—the capsular bag—is usually off the table in a reoperation. Instead, surgeons must identify a different space for the replacement lens, and that new location depends on the eye’s anatomy after the first lens is removed. It also influences the choice of fixation technique.

Here, experts share the approachesthey use, along with pearls for completing successful cases.

Active vs. Passive Fixation

There are two general categories of IOL fixation—passive fixation and active fixation.

Passive fixation is possible in the capsular bag, provided there’s enough capsular support; the ciliary sulcus; and the anterior chamber with a typical anterior chamber lens. “It’s rare to have enough good capsular support to put a lens in the ciliary sulcus with passive fixation,” says Kevin M. Miller, MD, chief of the Cataract and Refractive Surgery Division and director of the Anterior Segment Diagnostic Laboratory at UCLA. “Usually, the capsule and zonules are damaged. In an ideal situation, passive implantation in the sulcus with optic capture could work, if the capsulorhexis is the right size. If the capsule and zonules are damaged or completely gone, then you need to find another way of fixating the lens.”

Active fixation involves securing the IOL haptics to part of the eye. In the United States, suturing a lens to the back of the iris in the ciliary space is an option. In other parts of the world, iris clip or iris claw lenses are available. These lenses attach to the posterior or anterior surface of the iris.

There are three types of active fixation to the sclera: inner scleral; intrascleral; and transscleral fixation. “With inner scleral fixation, the haptics are secured to the sclera with sutures, either 9-0 Prolene or CV-8 Gore-Tex.” Dr. Miller says. “Intrascleral fixation involves creating a tunnel in the sclera, as initially described by Gabor Scharioth and modified in Amar Agarwal’s glued IOL technique. Transscleral fixation was popularized by Shin Yamane and many others after him, and it involves taking the haptics all the way through the sclera from the inside of the eye to the outside and melting the distal haptic to create a bulb, which is pulled back into the sclera.”

|

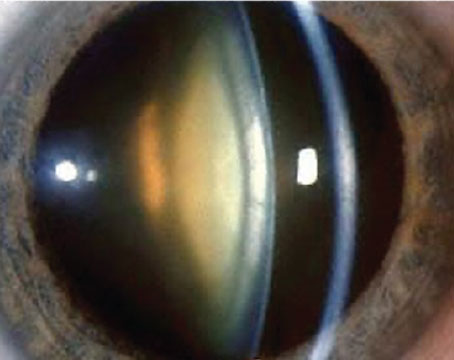

| Figure 1. In the Yamane technique, the new IOL for scleral fixation is inserted into the anterior chamber and a toric marker is used to mark the 6 and 12 o’clock meridians where the haptics will be externalized. All Images: David Xu, MD. |

Retina Specialist Support

For some dislocated lens cases, partnering with a retina colleague may be necessary. “If the lens implant is in the anterior half of the vitreous cavity, I do those cases alone,” says Dr. Miller. “But if it’s sitting on the retina, it’s often best to have a retina specialist there to do a good vitrectomy, lift the lens off the retina and then perform a check of the peripheral retina to ensure there are no tears or breaks and treat any that are there.”

The Anterior Chamber

Anterior chamber IOLs are often a source of contention among surgeons. Proponents of AC IOLs emphasize the importance of patient selection when using these implants, since anterior chamber anatomy and corneal health play a major role in determining the long-term success of the lens. “These lenses aren’t for every eye,” says Dr. Miller. “They get a bad rap because they’re often put into eyes with compromised corneas to begin with. However, I have patients who I implanted with an AC IOL 30 years ago, and their corneas are healthy and their vision is still good.”

Still, many surgeons avoid AC IOLs altogether, pointing out that these implants may lead to scarring, irritation, glaucoma, CME and corneal edema. “I’d much rather deal with the complications of a dislocated posterior chamber lens than the complications of an anterior chamber lens,” says Steven G. Safran, MD, who’s in private practice in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, who adds he’s never used anterior chamber lenses in his practice, though he’s removed quite a few. “The problems [they cause] are very difficult to fix. There’s often high astigmatism, glaucoma, scarring and fibrosis in the angle. They’re difficult to take out.”

For AC IOL candidacy, Dr. Miller offers the example of a patient with Marfan’s syndrome who already had problems with a lens implant dislocating in the posterior chamber. “In the prior surgery, the ophthalmologist sutured a capsular tension ring to the sclera,” he says. “Now the sutures have loosened, there’s a wobbly capsular bag, and the posterior capsule is open. How might you salvage this, given the difficulty of re-suturing the lens?

“In this case, I would take out the current PC IOL and put an in AC IOL,” he continues. “In a Marfan’s patient, the concern is that they’re already at high risk for retinal detachment, so the more time you spend behind the iris with needles, the greater the chance of a detachment later.”

Every case is unique, and the anatomy and prior eye history will help determine what type of secondary IOL technique will work best in a given eye. Dr. Miller shares the following tips for selecting eyes for potential AC IOL placement:

• Avoid distorted pupils. “The most commonly used AC IOL lens’s optic measures 5.5 mm, so if the pupil is deformed in such a way that it exceeds the diameter of that 5.5-mm optic centered in the eye, then this lens isn’t a good choice,” he says.

• Avoid anterior synechiae. “Adhesions between the iris and cornea leave little room for positioning an AC IOL,” he says. “Breaking those synechiae often results in iris defects, and you can’t have a lot of iris defects and expect a lens to fit well in the anterior chamber.”

• Avoid eye rubbers. Selecting patients who aren’t eye rubbers is vital. “I’ve noticed in past years doing AC IOLs that I’d slip them in through the incision and close it up,” Dr. Miller says. “Some patients would rub their eye, and then return later with irritation, and I’d find the haptic in the incision. So, I learned to put the lens in and rotate the haptics 90 degrees from the incision. If you make a temporal incision, rotate the haptics to 6 and 12 o’clock. Then, if the patient rubs their eye, the haptics aren’t going to spin into the incision. It’s also important to take care to protect the cornea when implanting these lenses. Use a dispersive viscoelastic if needed to avoid additional corneal trauma during the surgery.”

Appropriate sizing also contributes to the longevity of an AC IOL. “The haptics must be sized correctly,” says Dr. Miller. “Oversized, and you’ll get corneal decompensation; undersized, and the lens will rattle around inside the eye with eye movements and rotate. It’s a Goldilocks situation where it has to be just right.”

Initial lens sizing is usually based on the horizontal corneal white-to-white dimension. Dr. Miller adds 1 mm to this measurement. “I recently had a patient whose horizontal corneal white-to-white diameter was 11.5 mm,” he says. “I added a millimeter to get 12.5 mm and put in an AC IOL with a haptic dimension of 12.5 mm, and it fit very nicely. Proper sizing is important. If you put a lens in, sized initially, and it’s too big or too small, take it out and use a larger or smaller lens.”

|

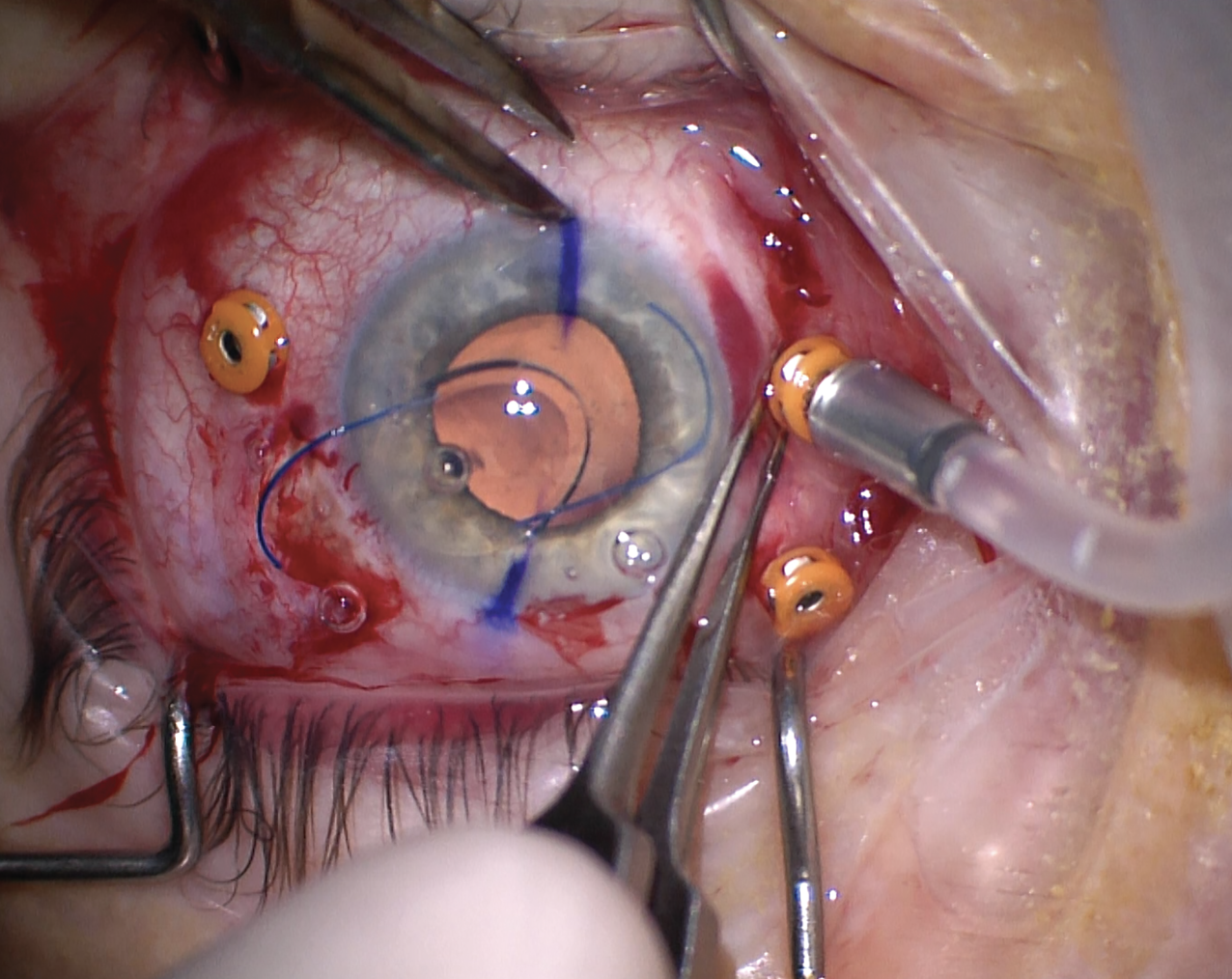

| Figure 2. The leading haptic is introduced into the lumen of a thin wall 30-gauge needle which has been tunneled through the sclera. |

The Iris

As with AC IOLs, iris-fixated lenses can work well in the right patients, surgeons say. However, surgeon experience and patient selection factor in heavily, as these lenses are attached to the delicate, vascularized uveal tract tissue.

“Suturing a lens to the iris may induce UGH syndrome and inflammation or cause cat-eyeing and other forms of pupil irregularity,” notes David Xu, MD, an assistant professor at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University and member of the Wills Eye Hospital Retina Service in Philadelphia. “Iridodonesis and phacodonesis may result. Pigment dispersion and secondary glaucoma are another potential complication. Additionally, the polypropylene sutures used for fixation have a long-term risk of breakage.”

“Iris suture fixation is fraught with more issues than other fixation approaches,” Dr. Miller says. “If there’s a lot of capsule behind the iris to stabilize it, you won’t have iridodonesis and you can suture lens haptics to the iris and get a pretty decent long-term result. But if there’s no capsular support, the iris tends to be floppy, and if you stick a lens on it, it’ll wiggle quite a bit when the eye moves. These patients often experience chronic iritis, which can lead to macular edema and other problems.

“When suturing a lens to the iris, ensure the suture passes are distal on the haptics to avoid creating an ovalized pupil,” he adds. “It’s difficult suturing so far out, but it’s necessary.”

Dr. Miller says he reserves iris suture fixation for the older patient whose lens is already in the ciliary sulcus, just decentered. “With older patients, I’m not worried about them having a lens sutured to the iris for 50 years,” he says, noting that for five or 10 years, it may be a reasonable option. “The other option would be to take out the decentered lens and replace it with a different lens and do more surgery. There’s a lot more trauma when doing a lens exchange—the operation tends to take longer. You have to consider the immediate effect of that longer surgery and the potential of its damage versus the long-term potential damage of sutures in the iris and lens jiggling around forever. There are many aspects to weigh. For a young patient, I don’t generally suture-fixate lenses to the iris. I’d rather suture-fixate the lens to the sclera.”

|

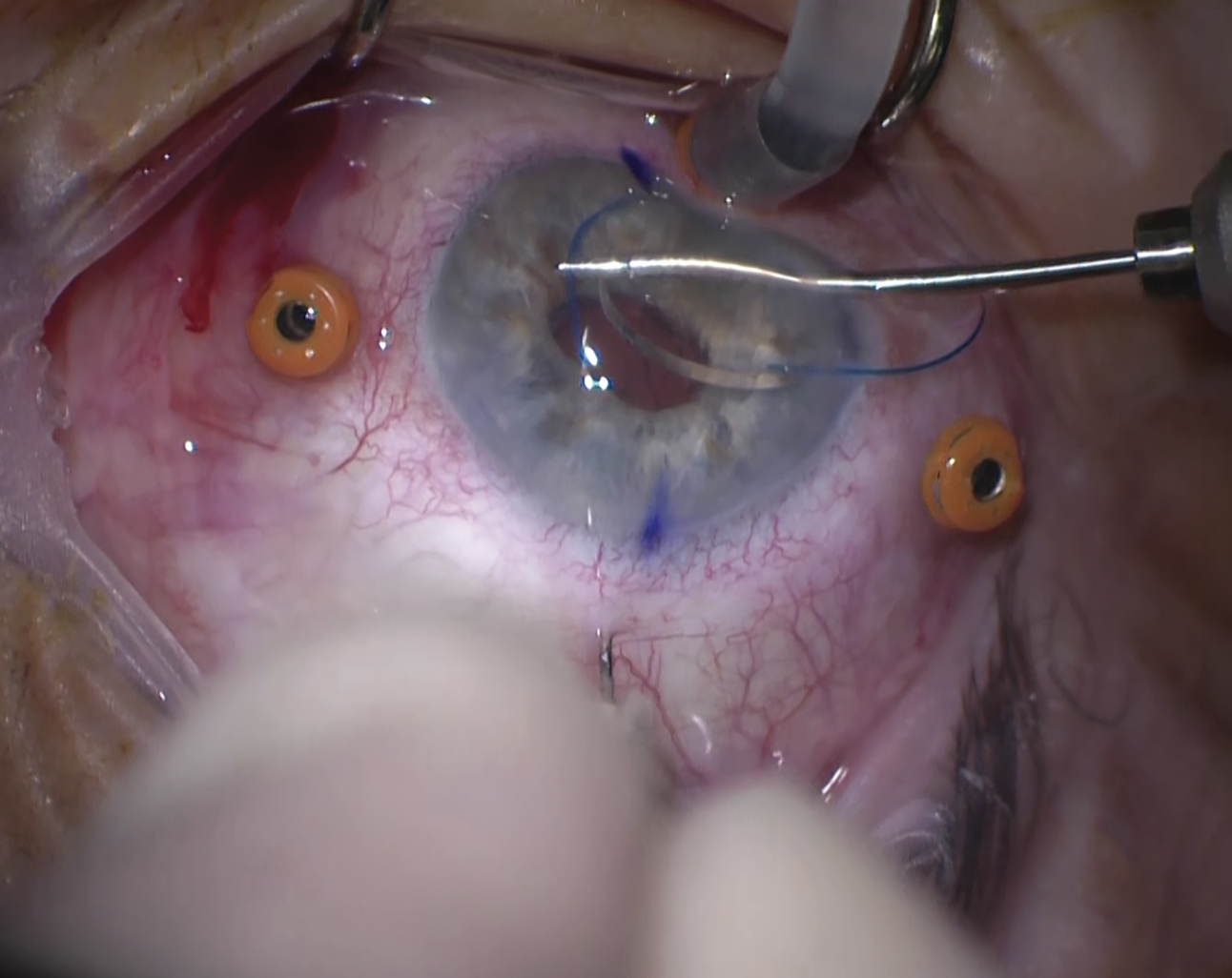

| Figure 3. The trailing haptic is introduced into the 30-gauge needle in the same fashion as shown in Figure 2. This allows the haptics to be externalized out of the scleral tunnels. |

The Sclera

Scleral fixation has gained popularity over the last several years, with the Yamane technique at the forefront. “Scleral fixation is a very technique-dependent procedure,” explains Dr. Safran. “It depends on the surgeon skillset quite a bit. I used to suture lenses to the sclera using Prolene or Gore-Tex through the eyelets of a lens like CZ70BD. Then from about 2012 to 2016 I’d externalize the haptics and tuck them into a scleral groove and cover it with a flap and do glued IOL. Once the Yamane procedure came out, I transitioned to that. Now I mostly do all Yamane.

“The Yamane is a nice procedure because you don’t have to touch the conjunctiva or damage the ocular surface,” he continues. “You can do it through a 2.75-mm clear corneal incision, though it must be done with a proper vitrectomy or else you’ll be engaging vitreous.”

“I’ve done a range of [scleral fixation techniques] in patients with complete aphakia and no capsular support,” Dr. Xu says. “These days, I prefer to do the Yamane technique. It’s a sutureless, flanged scleral haptic fixation technique. In the past, I did Gore-Tex fixation.”

|

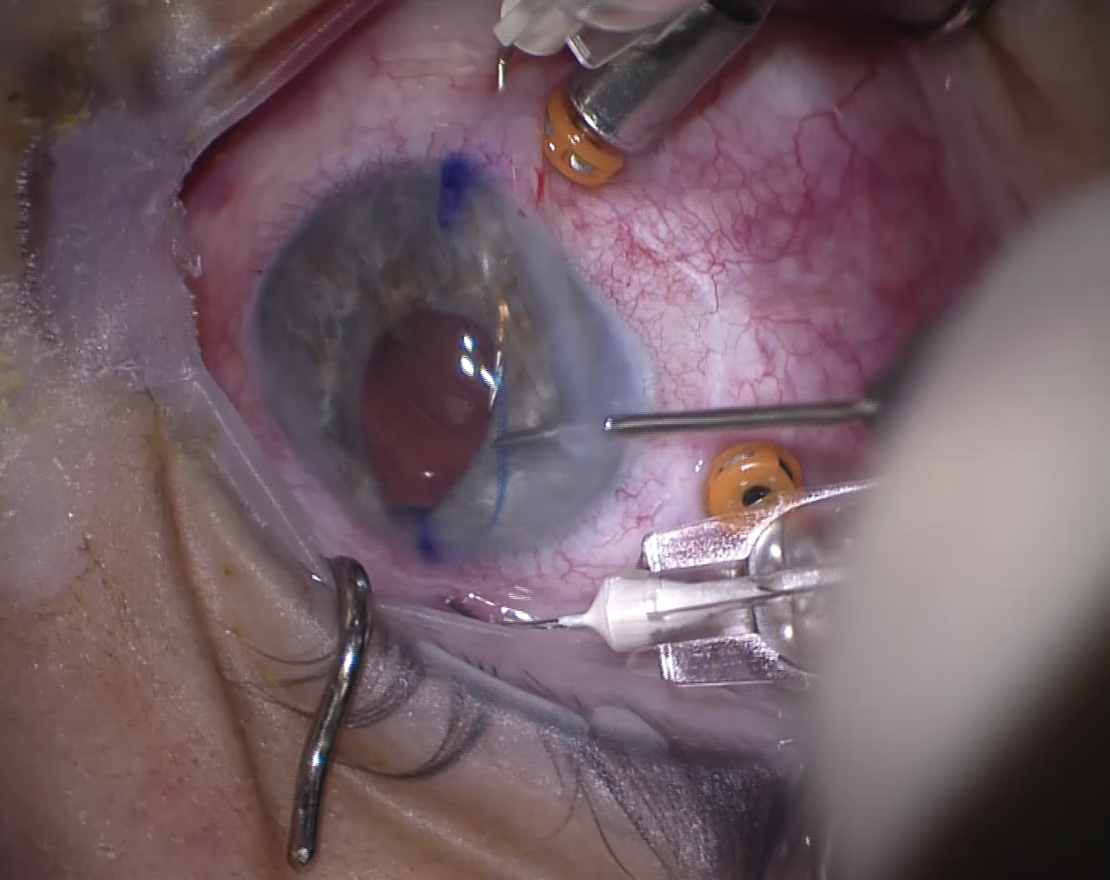

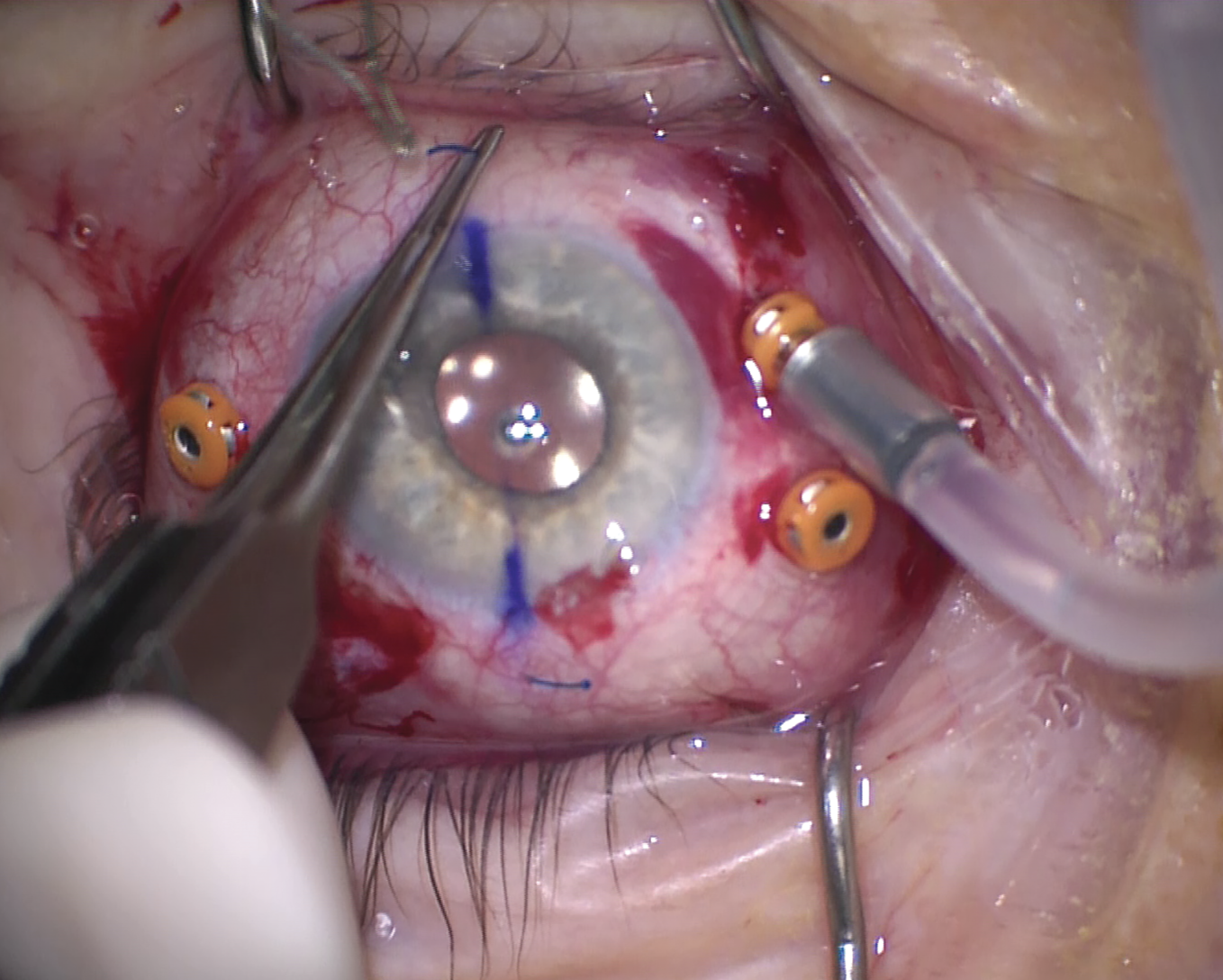

| Figure 4. With both haptics externalized, a terminal bulb is created using low temperature cautery. |

Dr. Xu says the Yamane technique has a steep learning curve, but once you get it and you’re comfortable with it, it’s a very efficient procedure. “Two important factors to keep in mind when doing the Yamane technique are making sure that the corneal incisions and where you’re planning to externalize the haptics are all set up exactly,” he says. “Precision is key, otherwise it’s a big struggle on the inside of the eye to get everything lined up.

“The second thing that makes a difference is the angle at which you insert the needles to do the fixation. If you’re not exact in the angle and direction that you’re inserting those needles during Yamane, then the IOL will come out tilted. Intraoperatively, if you see that, you can repass the needles. If you don’t catch it intraoperatively, there’s not much you can do except take the patient back to the OR.

“When doing the Yamane technique, I make a corneal incision temporally and fixate the haptics at six and 12 o’clock,” he continues (Figure 1). “Always do the leading haptic on the left-hand side of the eye, regardless of whether it’s the right eye or left eye. When you grab the haptic, grab at the midpoint and flex it a little so that it slides smoothly into the needle (Figures 2-3). The bevel of the needle and where you orient it is also important. It needs to be beveled in such a way that it catches the natural curve of the haptic going in towards the movement of the needle. This is true for both sides of the eye. The second haptic, the trailing haptic, is more challenging because there’s less space within the temporal part of the anterior chamber you’re working in. Making sure you have enough space there and setting up your grab points for where you’re holding the haptic is incredibly important.”

Hypotony is a potential danger with scleral fixation techniques. “For Yamane, I recommend suturing the main corneal wound, hydrating all corneal wounds and checking to ensure they’re water-tight,” says Dr. Xu. “I also suture all sclerotomies in. For four-point fixation, ensure the exit sites for all the sclerotomies are reasonably water-tight. If they look like they’re still gaping open, another suture can be placed to close it up.”

There are several IOL designs used for the Yamane technique, but Dr. Xu cautions that some of these IOLs have different haptic angulations, which will affect IOL calculations. “The popular CT Lucia 602 and ZA9003 lenses and most others have an IOL haptic angulation of five degrees, but there are others, for example the MA60AC, that have a haptic angulation of 10 degrees. This difference changes the effective lens position by about half a millimeter or sometimes more, which could be refractively significant. So, if surgeons stick with one IOL design then they’ll be fine, but if they are switching between the various IOL designs, I encourage surgeons to look at the haptic angulation and make sure their postop refractions are within the range they desire and make corrections on IOL power as needed.”

Dr. Safran has used both the CT Lucia 602 and AR40 lens for the Yamane technique. “The CT Lucia 602 is ideal for scleral fixation because of its robust polyvinylidene fluoride haptics, which don’t kink and have very good memory,” Dr. Safran says. “You can twist them, and they go right back to their original shape, whereas if you twist the PMMA haptics of an AR40, they’ll kink or even break. However, the AR40 has a 6-mm functional optic, which makes it a bit more forgiving in terms of centration.”

To use the AR40 requires some technique modification. “The flanges of the CT Lucia 602 produce a mushroom shape [when melted using low-temperature cautery],” Dr. Safran says (Figure 4). “If you melt the PMMA haptics on an AR40, you get a lightbulb shape which isn’t quite as secure. However, if you hold the AR40 haptic about 1 to 2 mm from the tip and melt it into the forceps, this will produce a more mushroom-shaped flange.”

He also notes that the AR40 haptics are thicker, which may require using a different gauge needle or modifying your approach. “The needle we use to capture the haptic is a TSK 30-gauge needle, and its lumen is 192 µm on average,” he says. “The CT Lucia 602 haptic is about 147 µm thick and the AR40 is 180 µm thick, so it’s a little harder to put the 180-µm haptic into the 192-µm lumen of the needle. Some surgeons use a 27-gauge needle for this. It’s important to match the angle of the needle and the haptic. Any off-axis attempts to get the haptic in the lumen won’t work and you’ll end up damaging the haptic.”

Here are several pearls for performing other scleral fixation techniques:

• Take care to keep sutures organized. “For the Gore-Tex procedure, surgical efficiency can be improved by ensuring the sutures aren’t getting tangled outside and inside the eye,” says Dr. Xu. “Sometimes the sutures can become looped inside of the eye. Be sure you have clear visualization to check that the IOL is in the right place.

“When doing Gore-Tex four-point fixation, I like to thread two of the Gore-Tex sutures through the eye while the IOL is still outside of the eye,” Dr. Xu continues. “Then, I introduce the IOL into the anterior vitreous plane and then externalize the remaining two sutures. I prefer using the MX60 lens for four-point fixation. It creates a pseudo four-point fixation using one eyelet on each side. Another suitable IOL is the Akreos AO60 lens. This lens is easier to use because it has four fixation points, which reduces the risk for inappropriately looping sutures. However, it has the chance of opacification with gas and is incompatible with silicone oil.”

When would you choose four-point fixation over Yamane? “If a patient has a dislocated IOL and it’s a PMMA IOL,” Dr. Xu says. “In those cases, a large scleral tunnel incision needs to be made and you often run out of room within the limbus of the eye to put the Yamane lenses in, between the large scleral incision and all the trocars. With the Gore-Tex procedure, it’s a bit more facile because the sutures exit at the same place where the trocars are, thus saving more real estate around the eye.”

• Sutures should exit on the top of the IOL. “No matter which IOL design you’re using, the sutures should exit the IOL flanges on the top of the IOL,” Dr. Xu says. “This will prevent any iris-IOL chafe.”

• For inner scleral fixation, ensure sutures bisect the pupil precisely. This helps avoid having a decentered lens. “Even if it’s perfectly centered, the lens can still be torqued or tilted, inducing cylinder as a result,” says Dr. Miller. “You have to make sure your suture passes are appropriate.”

• Don’t pull sutures too tightly. “Some lenses have fixation eyelets and some just have haptics,” he says. “You have to be careful that the sutures don’t pull off the end of the haptics as you’re tightening them. Additionally, if using Prolene, ensure that the sutures’ ends and knots are buried well by sclera. We often use Prolene inside a Hoffman pocket. If using Gore-Tex, make sure the knots aren’t exposed on the sclera because they’ll erode right through the Tenon’s capsule and conjunctiva. Bury Gore-Tex knots inside the sclerotomy.”

• Tunnel carefully when performing intrascleral fixation. “When performing intrascleral fixation, make sure your tunnels are nice and long,” Dr. Miller advises. “Use haptics that aren’t going to kink or break when you insert them into the tunnels. It’s also key to construct your tunnels in such a way that the lens isn’t tilted or decentered.”

• Caution patients against eye rubbing. “Warn patients that if they start rubbing their eye postoperatively, they could end up backing the haptics out of the tunnels, causing a dislocation just from eye rubbing,” says Dr. Miller.

Expanding Skillsets

The bulk of lens exchanges are done by only a handful of surgeons, says Dr. Miller. “Many surgeons just aren’t comfortable with these secondary IOL procedures, but they need to become comfortable because there will be a lot more of them in the future. As a field, we have more and more patients returning a decade after having flawless cataract surgery with dislocations due to trauma, the effects of retinal detachment repair, and diseases such as pseudoexfoliation.”

Dr. Safran is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Miller is a consultant for Alcon and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Xu has no related financial disclosures.