After a long wait, ophthalmologists are finally able to use the Morcher capsular tension ring, thanks to its approval in the fall of 2003. Though the ring allows you to offer certain patients a greater measure of safety during their cataract procedures, issues such as how to determine which patient will need a ring, when to implant it during the case and what size to use can still be puzzling at times. In this article, I'll share the knowledge I've gathered during my seven years of experience working with capsular tension rings to help you use them with confidence.

|

Preoperative Evaluation

Now that you have the option of using a capsular tension ring to aid your surgery on patients with weak or damaged zonular support, the first issue you run into is determining who will need one. To get at the answer, you have to look for obvious signs preop, as well as those that you may not have always considered.

In general, any patient who has loose zonules or whom you suspect will develop loose zonules later is probably a good candidate for a capsular tension ring. The first thing to take note of is a history of previous radial keratotomy, vitrectomy, trabeculectomy or any kind of blunt or penetrating trauma that might have weakened the zonules.

Surgical interventions are significant because, when the anterior chamber is opened, and, especially when it's unstable, the lens-zonular complex can trampoline, weakening the zonules. For example, with RK, if the patient had a microperforation, the chamber may have shallowed slightly before the perforation healed. Then, when the chamber returned to normal, the zonules will have been stretched somewhat. The same is true for vitrectomy and trabeculectomy. Add to this the continued instability postoperatively with vitrectomy because of a deficient vitreous-base support, and with trabeculectomy because of varying shallowing and deepening during the postoperative healing process, and you have stretched, weakened zonules.

After noting the patient's history, look for signs of zonular instability. I divide the preop evaluation of zonular weakness into two types: segmental and diffuse. The first is usually the result of trauma and involves a patient who has mostly strong zonules, save for a sector in which they're weak or absent. The second is characterized by a general degeneration of the zonules, such as in conditions like pseudoexfoliation or the rarer Weill-Marchesani and Marfan's syndromes.

When looking for diffuse weakness, especially pseudoexfoliation, be sure to check several things: the anterior surface of the lens, the pupillary ruff, the anterior surface of the iris, the corneal endothelium, which can be difficult to see; and the anterior chamber angle. Confocal microscopy (or endothelial photography) may aid in detecting endothelial pseudoexfoliative material, and gonioscopy may reveal otherwise undetected signs. Performing these additional tests preoperatively has enabled me to identify pseudoexfoliation in patients who otherwise may have gone undetected. Also, watch for any abnormal deepening of the chamber and lens movements. If you measure chamber depth you may notice asymmetric measurements.

In some patients, you may actually be able to see the loose zonules. In other cases, however, especially trauma, it's difficult to see the extent of the zonular damage. In these instances, my rule of thumb is, "Whatever you think you see at the slit lamp, double it." Often, you think you're dealing with three or four clock hours of dehiscence or loss based on your exam, but when you get to the OR you see that half the zonules are gone.

| A Sign of Rings to Come |

|

| This year, Morcher will seek a second approval, this time for a modified version of its already-approved rings. Also, a set of rings made by Ophtec (Groningen, the Netherlands) for indications similar to those of the currently approved Morcher rings is due to be approved for sale in the United States in 2004. Hillard Welch, U.S. regulatory affairs manager for Morcher, says he soon plans to submit data to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on what is known as the Cionni modification to its capsular tension ring, named after its developer, Cincinnati Eye Institute surgeon Robert Cionni. The modified ring is aimed at patients with profound zonular weakness. "The modification places an eyelet in the ring so the surgeon can suture it to the sclera," explains Mr. Welch. "This allows him to stabilize the placement of the ring. In these patients, if you were to put in a standard ring without the eyelet, it could move within the capsule." The Cionni ring will come in three forms: one with a single-suture eyelet, one with two eyelets and one that can be used with an injector. The rings could be used when zonular dehiscence is up to 180 degrees, he says. Mr. Welch expects to be submitting the data for the Cionni rings, gathered from around 100 cases, sometime in 2004. Advanced Medical Optics (Santa Ana, Calif.) has agreed to market and distribute the Ophtec rings in the United States when they're approved. "The rings will be for the management of suspected or observed weakened, broken or missing zonules in complicated cataract surgery," says Abby Markward, AMO's refractive marketing manager for the Americas region. "They'll be usable if three to five clock hours of zonules are missing or weakened." She says that Ophtec underwent an FDA audit of its manufacturing facilities in mid-January, which went well. "We're just waiting for our approval letter," she says. The rings are due to come in two sizes: 12 and 13 mm, and will be of a similar design to the Morcher rings. They're made in a compression molded Perspex CQ PMMA process that Ms. Markward says affords them very good flexibility in the eye. |

During the procedure, be aware of marked instability in the anterior chamber. For example, when you insert the infusion tip, you may see a sudden, pronounced deepening of the chamber; the lens-iris diaphragm will move back considerably into the posterior chamber. With this deepening of the chamber, you'll notice excessive dilation of the pupil. Other signs would be the capsule moving away from you every time you press down on it to start your capsulorhexis and difficulty in completing the rhexis.

In addition, watch for signs of vitreous prolapse around a segment of zonules, which may not have been evident at the slit lamp. In such cases, if it's not clear that there's vitreous in the anterior chamber, you may want to inject some Kenalog (triamcinolone acetonide, Bristol-Myers Squibb) into the area of suspected vitreous prolapse, a technique first described by Tulane University surgeon Gholam Peyman in 2000 and later popularized by Scott Burke, MD, PhD, of the Cincinnati Eye Institute. If vitreous is there, it will appear as white particles.

• Contraindications. This isn't an easy call to make, as a capsular tension ring can help with many patients. In the U.S. Food and Drug Administration study of the Morcher rings, most of the study patients (59 percent) had up to 90-degree zonular dehiscence at the time of surgery For a significant amount of zonular dehiscence, a variation on the Morcher ring, the not-yet-approved Cionni ring, may be useful (See "A Sign of Rings to Come," below).

Also, I wouldn't use a ring on a patient with an anterior capsulorhexis or posterior capsular tear unless it has been converted to a continuous circular rhexis, because centrifugal tension from the ring may cause the capsule to split open along the "fault line."

Inserting the Ring

There are no hard-and-fast rules about when to insert the capsular tension ring during the case. My advice is to put the ring in as late as you can but as early as you need it, because the more cataract you remove, the easier it is to insert the ring. On the other hand, early insertion may stabilize the lens and make surgery less risky. Here are some tips to keep in mind.

• Making the capsulorhexis. Since patients with zonular dehiscence may be more prone to developing postop capsular contraction, it's a good idea to have a decent-sized capsulorhexis by the end of the case. If it's too big, however, there's a chance it may stray and tear radially. I think a 5.5-mm capsulorhexis is probably ideal, since it will cover the edges of the implant. There is evidence to suggest that covering the implant's edges results in less capsular contraction or PCO.

• Phaco "tips." When working with patients with weak or absent zonules, it's best to use a phaco technique that doesn't put a lot of posterior stress on the lens. I prefer to use a chop or supracapsular technique, because either allows me to raise the nucleus above the capsule, putting less stress on the zonules.

If you use a divide-and-conquer or stop-and-chop technique, make sure the phaco power is relatively high, so it will do the cutting through the nucleus for you. This is similar to what Boston surgeon Roger Steinert calls the "knife through butter" approach.

Another nice technique is viscoelevation. This involves a traditional hydrodissection followed by a second viscodissection of the nucleus with a retentive viscoelastic. The viscoelastic pushes the nucleus up, allowing you to phaco it in a gel medium rather than in its capsule. This technique is particularly good for a patient with a shallow chamber in whom you want to protect the capsule but where a supracapsular technique would bring you too close to the cornea.

Also, you'll probably want the fluid infusion to be a little lower in the patient with weak zonules, and to avoid sudden pressure surges that may place undue stress on the zonules.

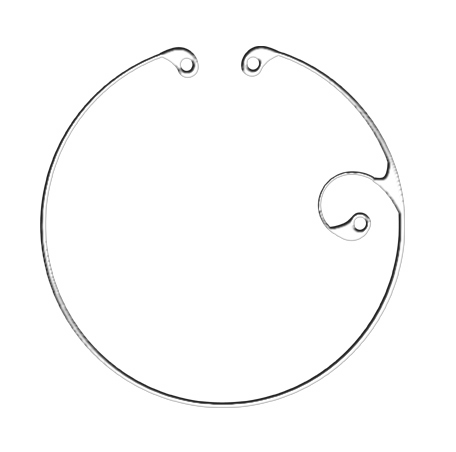

• Sizing. Though some may have thought capsule size is related to axial length and have used that as a basis for choosing a CTR size, there is better correlation between capsular diameter and the white-to-white measurement. So, when choosing which of the three sizes of currently approved CTRs to use, factor in the white-to-white measurement, which can be made either with a caliper or, more accurately, with optional software available on the IOL Master.

The other factor to use is a subjective appraisal of the degree and type of zonular laxity. This is something that will become easier with experience. So, someone with a small white-to-white measurement and not much zonular laxity could do well with a small ring. A person with a large white-to-white measurement and marked laxity, however, might do better with a larger diameter ring.

• Insertion. When I make the capsulorhexis, I like to remove the anterior and equatorial cortex in order to create a space for placement of the CTR. If I'm putting a ring in before the phaco, as is often necessary, I then inject a retentive viscoelastic under the anterior capsule to push the nucleus and cortical material as far posteriorly as possible and create a space immediately under the anterior capsule. Next, I use a CTR injector (Geuder, Heidelberg, Germany; or Ophtec, the Netherlands) to insert the ring right under the anterior capsular rim so that it enters the capsule with as anterior an approach as possible. This is important because the CTR tends to trap cortex. By pushing the cortex and nucleus back, however, and placing the ring as far anteriorly as possible, you probably won't trap much cortical material.

When I'm inserting the ring with the injector, I don't like to advance the ring along the inside of the capsule, because the leading edge of the ring may pierce the capsule. Instead, I put the distal terminus of the ring as far around the circle as I can, and then leave it there. Then, as I inject the ring forward I actually back out with the injector so that the ring stays relatively steady and doesn't migrate. This technique also allows you to place the fundus of the ring, which I feel is the strongest part, in the most unstable part of the bag.

After the ring is in place, I prefer to wait a few minutes. This delay allows the ring to create some stability, because, once you've placed it, the zonules will recoil initially, since they're no longer under tension. Then, they will tighten up a little again, which you can actually visualize. After waiting a few minutes, you can then do the phaco with a more stable capsule and zonules.

• Closing the case. The cortical cleanup step is more a matter of prevention. First and foremost, try to avoid capturing cortex.

If there is any cortex trapped behind the CTR, use a low, steady flow and just keep working at it. You can go in with a blunt instrument and pull back the ring to free the cortex behind it. Remember, though, if you pull on one side of the ring, you'll momentarily weaken that side of the capsule.

The caveat for cortical cleanup is to always remember that it's inherently more difficult in patients with weak zonules, so you should probably approach it less aggressively than you normally would. When it comes to cortical cleanup, the enemy of "good" is "better"—don't strain to get the last pieces if it's going to be too difficult.

Sticky Situations

Though inserting a CTR is relatively straightforward, knowing the best time to do it, and in whom, is more art than science. Here is how I would approach certain situations that might make a CTR decision difficult.

• Pseudoexfoliation. In patients with this condition, the zonular weakness tends to be very diffuse, so I find myself putting in CTRs most commonly at the beginning of the case. Unlike a trauma case in which some zonules may be damaged but the remaining ones are strong, in pseudoexfoliation the zonules are biomechanically weakened in general, and this weakness may progress.

For the first-time CTR user, it's probably better to try to put in a ring early, because it gives you an extra margin of safety that will make you feel more comfortable when dealing with eyes with loose zonules. Be sure to clear away the loose cortical material before implanting the ring, though, so as not to trap the material beneath the device. If you do trap cortex, a slightly risky maneuver involves hooking the eyelet of the CTR and then dialing it in the bag to free up the cortex. Since the capsule is already unstable, however, this maneuver may actually destabilize it. Therefore, use this technique with care.

• Trauma cases. In these instances, you may be able to use a retentive viscoelastic to hold open the edge of the capsule without zonular support and do almost the entire case without needing to use a CTR until the end, when it can lend extra support.

If a trauma patient has between one and four clock hours of dehiscence, there's probably little difference in the approach, and there are enough supporting zonules remaining. Usually, even four clock hours of dehiscence respond very well to the use of a CTR, because the remaining zonules are very strong and can buttress the lens through a cantilever effect.

|

|

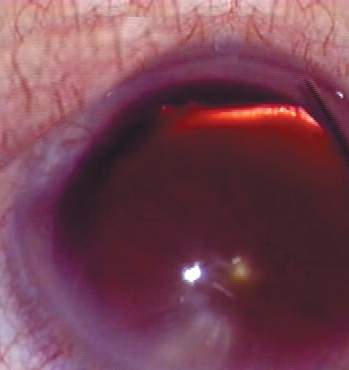

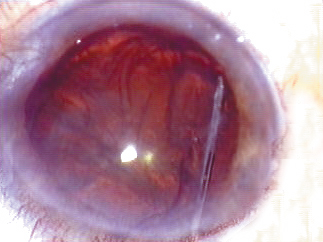

| An eye with zonular dehiscence (left) that was then stabilized with a ring (right). | |

If a trauma case has more extensive dehiscence past four clock hours, this can be problematic, because the lens will be unstable on one side. In these cases, you'll need additional support, either in the form of a suture through the CTR or, when it's approved, the Cionni modification, which allows for suturing to the sclera for additional support. Until this variation is available, however, you can use the following technique to enhance stability.

If a patient has no zonules left on half his capsule, implanting a CTR would keep the bag open but the side without zonules would tend to move posteriorly, since it has no support. To stabilize the situation, put one haptic and the optic in the bag on the side with stable zonules, leaving the remaining haptic in the sulcus, Then take the haptic on the weak side of the capsule and suture it to the posterior iris on that side using a modified McCannel technique. When this is done, the haptic is supported by the iris and is also attached to the lens, which is in the bag. The other side will be supported by the CTR and the intact zonules.

| Getting Reimbursed |

| The use of the capsular tension ring is one of the criteria cited in the use of the complex cataract code (66982), and you'll receive additional reimbursement if you have to use one. Use of the ring, however, is highly monitored, so make sure your operative note not only documents the use of the device, but also the reason you used it and a note about the outcome. At the time of this writing, facilities don't receive additional payment when a ring is used, but I and other surgeons hope they'll eventually get additional reimbursement to cover the cost of the ring and the added surgical time and resources needed.—K. Rosenthal, MD, FACS |

In pseudoexfoliation, however, the amount of tensioning is critical, because you're trying to take the overall stress off of zonules that are biomechanically weak. If you put one ring in, especially a smaller one, but you feel there still isn't enough stability, a second, preferably larger, ring can help provide a bit more centrifugal force.

Putting in too large a CTR causes the posterior capsule to be both displaced anteriorly and placed on tension, though. Then, as you remove the nucleus, the capsule will be much more vulnerable to damage. So, if you're using a large ring, or a ring that you know will add a lot of tension, be very careful to avoid the posterior capsule and place a retentive viscoelastic behind the nucleus to create a "safe zone." Be aware that, if you puncture the posterior capsule in a setting of that much tension, the puncture will propagate quickly.

• Complications. As one of a handful of doctors who've been involved in both CTR trials, Morcher's and Ophtec's, I have seven years' experience with the rings. In that time, I have experienced no complications in my own cases. In the clinical trials, there have been around two or three instances in which a ring punctured the capsule and the entire lens, capsule and all, had to be removed. There have also been instances where the ring didn't work, but stayed in the eye without causing a problem until it was removed.

Over the long term, I've had several CTR patients who went on to develop anterior capsular contraction and phymosis that required YAG anterior capsulotomy or surgery. I'm currently favoring surgery over YAG for such patients, because it's a more controlled procedure; if you YAG these cases, you could create a tear that would propagate across the capsule. Also, in cases that don't have a primary CTR, I've had good results in inserting a CTR after repositioning a luxated IOL caused by capsular instability.

The approval of the capsular tension ring is going to help a lot of surgeons and their patients, but it will take time for surgeons to become proficient with them. The toughest decision is determining who can benefit from a ring, and whose capsule is so far gone he should just have his lens and capsule removed. The more cases you get under your belt though, the easier this decision becomes.

Dr. Rosenthal is on the clinical faculty of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary and the North Shore LIJ Health Systems and is in private practice in New York City and Great Neck. He can be reached via e-mail at kenrosenthal@eyesurgery.org.