If patients have both wet age-related macular degeneration and geographic atrophy, the wet AMD almost always needs to be treated because it can significantly affect vision. Whether or not the GA requires treatment and whether it should be treated concurrently with wet AMD treatment depends on several factors. Here, retina experts explain how they approach these cases.

Background

Anti-VEGF injections are highly effective for treating wet AMD, while two new drugs—Syfovre (pegcetacoplan) and Izervay (avacincaptad pegol)—were approved in 2023 for the treatment of geographic atrophy.

“Wet AMD is a greater risk to vision, not so much in terms of quantitative impact, but in terms of timeline, meaning that you lose vision more quickly from wet AMD than dry AMD,” explains J. Sebag, MD, who is in practice at the Doheny Eye Institute at UCLA and president of VMR Consulting, in Huntington Beach, California. “Additionally, the evidence supporting the efficacy of treatment for wet AMD is far superior to the evidence supporting the efficacy of geographic atrophy treatment. Yes, treatment slows the rate of GA progression, but there’s no proof that slowing the rate of progression translates to better vision." Along these lines, Dr. Sebag references that the European Medicines Agency's (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has now twice recommended against marketing authorization for pegcetacoplan. The marketing authorization application for avacincaptad pegol for the treatment of GA secondary to AMD is still being reviewed by the EMA.

Dr. Sebag’s approach to treating patients who have both of these conditions is to treat the wet AMD and, once that has stabilized, then direct his attention to the geographic atrophy. “In the OAKS and DERBY trials of geographic atrophy, a percentage of patients developed wet AMD,” he notes. “It ranged from 2 to 11 percent in the OAKS study and from 4 to 13 percent in the DERBY study. Those patients were treated for both conditions concurrently. And that was driven by the clinical trial protocol, meaning they had to continue treating the geographic atrophy because they were in the study, but they were also obligated to treat the new problem, that being the wet AMD, concurrently. But that doesn’t necessarily translate to clinical practice, and I think that there will be a variance of treatment approaches amongst practitioners.”

According to David Boyer, MD, in practice in Beverly Hills, treating these two conditions isn’t a one-size-fits-all treatment. “Let’s assume you have a patient with geographic atrophy, and you’re treating him or her every four to eight weeks. Then, that patient develops a choroidal neovascular membrane. Do you want to treat that patient? Should you be treating both conditions at the same time to avoid the patient coming up and back? Some patients may not want to stay around to have the treatment, so if you do both eyes, you’re treating with the anti-VEGF first, and then you’re treating with your choice of geographic atrophy medication,” Dr. Boyer says.

Dr. Boyer normally does treat-and-extend. “In that patient, you may be able to extend the anti-VEGF to a much longer time period,” he says. “Where does the patient live? How inconvenient is it for him or her to come in? You may settle at eight weeks even though you know that you probably can go longer with your anti-VEGF as long as they remain dry. If the patient has glaucoma, his or her pressure probably won’t come down in 15 to 20 minutes. So, it’s going to be much harder for them to wait around the office. They’re already waiting for a considerable period of time just to get the one injection.”

|

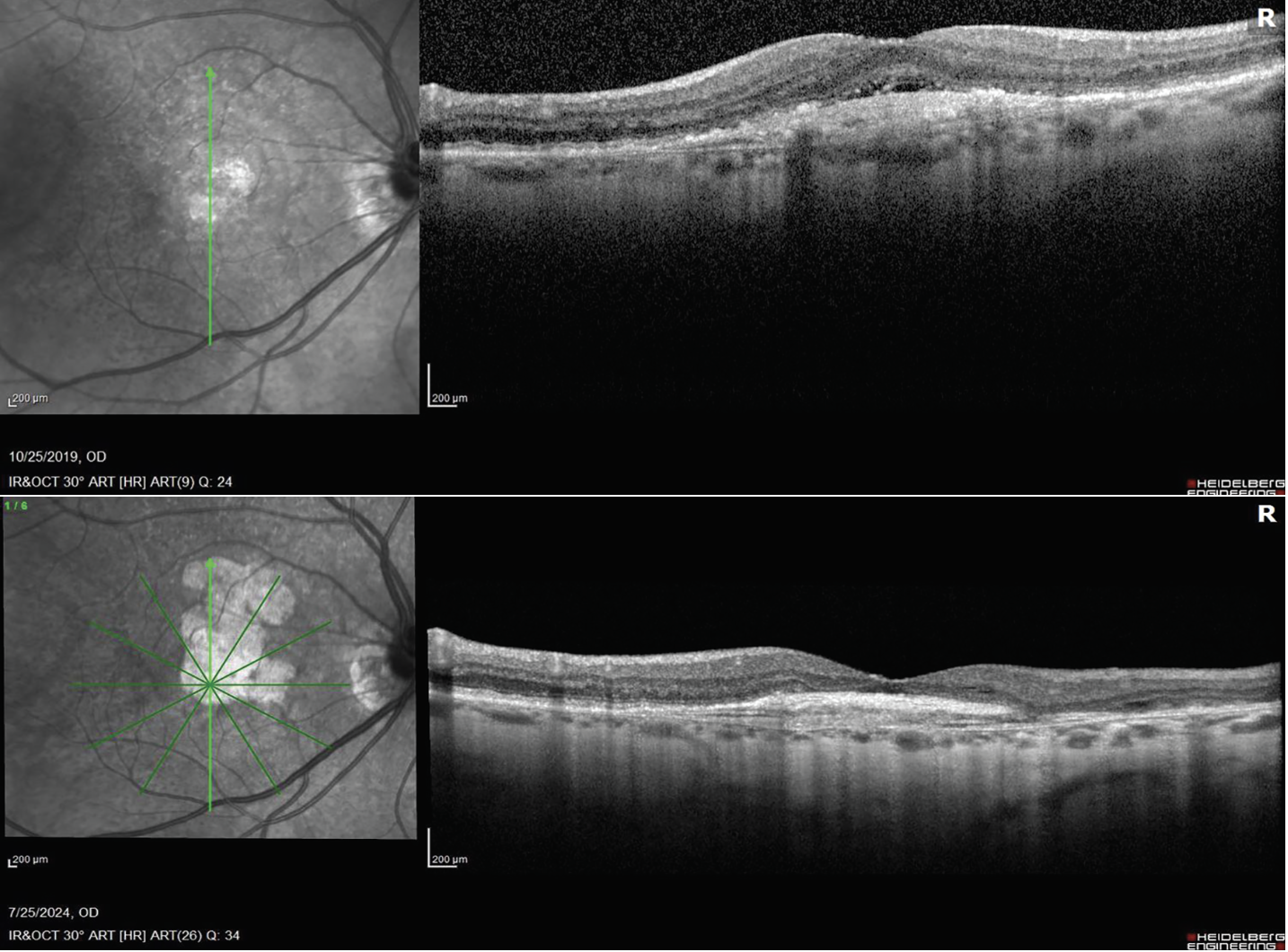

| First visit (top), the patient has wet AMD. At the most recent visit (bottom), the wet AMD is well-controlled with anti-VEGF injections, but the GA has really grown, and the patient is now on complement inhibitors. The treatment alternates between anti-VEGF and anti-complement, once a month. |

Another scenario is a patient who has neovascularization and then develops geographic atrophy. “You think you’ve got the wet under control, but the geographic atrophy is now starting to cause the patient problems,” Dr. Boyer says. “You’re already out two months or three months in treating the patient with anti-VEGF, so now you’ve got to taper. You might go six and 12 weeks. In other words, at six weeks, you would treat the patient with an anti-geographic atrophy drug, and at 12 weeks, you would treat them with both. A lot of my patients don’t like two injections given at the same time. Other patients want to minimize the number of visits. Sometimes, they’re wet in one eye and dry in the other eye, and you can work it out in the schedule so they get two different medications. You’ve got to use two different lots of medications if you’re doing both eyes, and it’s not easy on the patient to have two injections plus a tap if necessary.”

He lets patients choose whether they want to be treated concurrently or separately. “Most of the time, they don’t want to spend an extra 15 minutes here. Most of my patients don’t like two injections, for some reason, especially when you’re doing a tap. Additionally, you’re adding one extra chance of getting an infection, one extra needle in the eye. So, for me, I try to minimize as much as I can, but you have to listen to the patient and what the patient’s needs are,” he says.

Carl D. Regillo, MD, director of the Retina Service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, agrees that the active wet AMD needs to be treated and stabilized before considering GA treatment. An example is a patient who is undergoing treatment for geographic atrophy, and it turns wet. “In that scenario, I will sometimes continue the GA treatment, and sometimes I won’t,” he says. “However, I’ll be treating the wet AMD for sure. So, in other words, if I’m treating the dry, and I usually treat every six to eight weeks with one of the two GA drugs, and the patient’s affected eye turns wet, I factor in vision, symptoms, GA lesion size and location, fellow eye status, and how often the patient will need to come in to treat the wet AMD. There are a lot of variables, but at the very least, we know we must treat the wet AMD optimally and it’ll take months to know how often the patient will need to come in to control the wet component of the AMD.”

Dr. Regillo doesn’t treat the same eye on the same day with both treatments. “Continuing the treatment for GA depends a lot on the patient’s preferences, how often he or she needs the wet AMD treatment, and how easy it is for him or her to get to the office,” he says.

Another scenario is a patient with wet AMD, who’s been treated and stabilized, and he or she starts developing geographic atrophy that’s affecting or threatening vision. “I will occasionally treat those patients for their GA in addition to their wet AMD,” Dr. Regillo says. “I have patients who have been on wet AMD treatment and are doing really well. Then, over time, they start to have problems with geographic atrophy affecting their vision. I’ll speak to them about potentially treating their GA, too. I’ll treat the wet AMD, and then I’ll treat the GA on different days, not the same day, and coordinate the office visits to be the least burdensome as possible. So, for example, let’s say the patient is on wet AMD treatment every 12 weeks, I’ll treat that same eye halfway in-between at six weeks with the GA treatment, and then have him or her come twice around the 12-week point. However, these aren’t common scenarios. Usually, I’ll treat an eye with one condition or the other, very rarely both. At this time, I only have a handful of these types of patients where I’m treating both conditions in the same eye.”

Dr. Sebag notes that some cases of GA don’t require treatment at all. “If patients have geographic atrophy that’s not threatening the fovea, it shouldn’t be treated,” he says. “And if patients have geographic atrophy that’s already wiped out the fovea, that also doesn’t require treatment. There is a big difference between clinical trials and clinical practice. In practice, I have concerns that a lot of patients with chorio-retinal atrophy are being treated, and they shouldn’t be. So, in my use of those drugs, I limit it to patients who have geographic atrophy threatening the fovea. If the experience in the clinical trials is borne out in clinical practice, then that’s a useful treatment, but only in a subset of patients, and I have concerns that people may not be adhering to the criteria that I just described.”

Dr. Regillo agrees and says he doesn’t treat cases of geographic atrophy that are at the ends of the spectrum. “I wouldn’t treat geographic atrophy if it’s mild, and I wouldn’t treat it if it’s severe,” he notes. “If GA has already knocked the vision down, patients aren’t very likely to benefit from that treatment. Wet AMD is always a threat. Wet AMD almost always needs to be treated.”

Dr. Boyer adds that age also plays a role in the treatment decision. “If patients are successfully being treated with an anti-VEGF medication, and they develop some atrophy, do they really need to be treated if they’re 90-something years old?” he muses. “The medicines only reduce the progression; they don’t stop it. You don’t want to stop the anti-VEGF because that will cause a significant loss of vision. It’s a difficult decision.”

Dallas’ Karl Csaky, MD, PhD, says he doesn’t use anti-complement therapy extensively as a standalone approach. “The majority of our patients who are being treated with anti-complement are usually in a clinical trial,” he says. “A handful of our patients have wanted anti-complement therapy, and then I treat but it’s not something that I do routinely. We’re a big clinical research practice where we have probably four or five geographic atrophy trials, and most of our patients typically fit into one of those trials.”

Dr. Csaky has had several cases of choroidal neovascularization in the setting of anti-complement therapy. “One of the clinical points to consider is that the appearance of CNV in the context of anti-complement therapy may present somewhat differently than the usual appearance of the CNV,” he says. “Unlike our typical CNV patients, who develop excessive exudation, hemorrhage, and lots of fluorescein leakage, many of the classic features that we see in AMD patients who come into the clinic with CNV, for the patients who are on anti-complement therapy and develop some activity, the appearance can be more subtle in the cases that I’ve seen, albeit it has only been a handful of cases. In one case, for example, the patient presented with minimal thickening of the retina without frank intraretinal fluid.”

Dr. Csaky adds that performing fluorescein angiography may not be helpful because it’s very difficult to discern in a patient with GA what is just window defect, what is just noise, and what is a signal. “We know from lots of studies and experience that patients with GA tend to develop less active CNV,” he says. “The choroid and choriocapillaris can be thinner, so they don’t have the vascular hydraulic push that’s seen when someone has a normal-appearing choroid or choriocapillaris and then develops CNV. Those CNVs are much more active; there’s more exudation, it’s very clear.”

For this reason, he says that OCT-angiography has been particularly useful as it can help, in some cases, clearly delineate an area of CNV that may be otherwise difficult to diagnose. This can be especially helpful in determining if a small area of intraretinal fluid is simply due to the ongoing degenerative process or indeed CNV activity.

In these cases, Dr. Csaky has done both treatments on the same day, depending on patient preference. “Then, it’s just more of a logistic issue of what’s the best way to treat both. We typically don’t necessarily stop the anti-complement therapy, because there’s no reason to,” he explains. “We might hold one injection while we do the first anti-VEGF, as there may be other issues that come into play when you start doing two injections in the same day. So sometimes, we’ll hold off the anti-complement treatment and just do the anti-VEGF and then have the patient come back.”

Dr. Csaky says that, in his limited experience, the CNV tends to respond quite well. “We have done, for example, only one anti-VEGF, and we see improvement in vision. We have seen a prompt resolution of the disease, and then these cases don’t require frequent anti-VEGF injections,” he says.

Retina Industry News Cholesterol-lowering Drug May Slow Vision Loss in Diabetes Patients Findings from the LENS Trial revealed fenofibrate, a medication used for many years to reduce blood fat levels, significantly reduced the progression of diabetic retinopathy.

Vabysmo Prefilled Syringe’s New Indications The FDA has approved the Vabysmo 6 mg single-dose prefilled syringe for use in the treatment of wet AMD, diabetic macular edema and macular edema following RVO. Vabysmo will continue to be available in a 6-mg vial. Vabysmo PFS will become available to U.S. retina specialists in upcoming months, the company says.

MacTel Treatment Gets Priority Review Neurotech Pharmaceuticals announced the FDA determined that the Biologic License Application for NT-501, an investigational encapsulated cell therapy for the treatment of MacTel, warrants a substantive review. The application has a prescription drug user fee act goal date of December 17.

Dry AMD Treatment Reaches Phase III Stealth BioTherapeutics enrolled and dosed its first patient in the ReNEW trial for elamipretide in patients with dry AMD.

Ocugen Retinal Trials Advance Ocugen announced the first patient was dosed in its Phase III liMeliGhT clinical trial for OCU400, a gene therapy candidate being developed for retinitis pigmentosa. The company also announced it will proceed with a high dose of OCU410ST, a gene therapy candidate for Stargardt disease.

Cohort III and Phase II Approved for Simultaneous Enrollment in ArMaDa Study Ocugen announced a positive outcome of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board Review for its Phase I/II ArMaDa clinical trial for OCU410 (AAV5-hRORA), a modifier gene therapy candidate in development for geographic atrophy. Six subjects with GA were dosed in the Phase I/II clinical trial to date—three with the low dose and three with the medium dose. An additional three patients will be dosed with the high dose of OCU410 in the dose-escalation phase. |

Dr. Regillo is a consultant to and receives research support from Apellis and Astellas. Dr. Sebag has no financial interests to disclose. Pertaining to products or product categories mentioned in this article, Dr. Csaky has a financial interest in Genentech, Heidelberg Engineering and Regeneron. Dr. Boyer is a consultant to Bayer, Genentech, Optos, OptoVue, Regeneron and Roche.