The stress produced by unmet expectations can be even more disturbing. Many individuals became ophthalmologists partly so they could have a 9 to 5 job. Today, if somebody shows up in the emergency room after hours with a problem relating to the eye, doctors in training are petrified about getting sued for treating beyond their knowledge domain, so they call in an ophthalmologist.

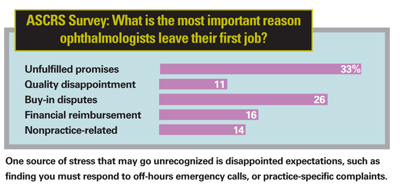

Practice-specific expectations are frequently unmet as well. A recent survey of members of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, conducted by the ASCRS Young Physicians and Residents Committee and reported at this year's ASCRS meeting in San Francisco, found that the reason most often given for leaving a first job in ophthalmology was "unfulfilled promises." (See chart, right.) And when asked "How do income, autonomy, and prospects compare to what you thought they would be?" more than 60 percent of respondents said they were less than expected. Finding that your career is "not what you signed up for" can generate a lot of anxiety.

|

Nevertheless, there's a lot of truth to the saying that pressure is on the outside while stress is on the inside. The proof lies in the fact that many ophthalmologists are quite comfortable working under these conditions. As John Pinto, president of J. Pinto & Associates Inc., a well-known ophthalmic practice management consulting firm, notes, "Some doctors walk into their operatory, do 30 or 40 cases a day, deal with all kinds of complications and come out cool as a cucumber. Others may have one or two cases in the morning, but before they can start they have to head to the washroom and throw up because they're so profoundly stressed."

Some of this difference would undoubtedly be genetic, but at least two huge components of stress are within our control: our perspective about what's happening; and having stress management skills. In that spirit, we've asked two experts and several ophthalmologists to share what they've learned about managing the stress that comes with being a practicing ophthalmologist.

The Nature of Stress

To manage stress, it's essential to understand two key facts. First, stress can be produced by positive events and circumstances as well as negative ones. Surprisingly, the internal stress that results is just as hard on your mind and body. Mr. Pinto recalls the groundbreaking work on the subject of stress done by Hans Selye in the mid-20th Century. "Selye observed that any kind of change, whether positive—like having a child or changing to a better job—or negative, like losing a job or spouse—leads to stress," he explains. "At a physiological level they're indistinguishable."

The second thing about stress that's important to understand is that it can be a good thing; it only becomes a bad thing when you have more of it than you're able to manage. "Anxiety caused by stress can enhance your performance," says Mr. Pinto. "Lots of studies in athletics have shown that an athlete won't perform well if he's too stressed—or if he isn't stressed enough. There's a sweet spot between those two extremes that optimizes performance. The trick is to set the right standards—just enough of a challenge to do your best work."

Acting In vs. Acting Out

To get the perspective of an expert who makes his living helping doctors deal with stress, we spoke with John-Henry Pfifferling, PhD, founder and director of the Center for Professional Well-being in Durham, N.C. The center has been devoted to promoting well-being among health-care professionals' practices and families since 1979, through education, consultation, interventions and seminars. Dr. Pfifferling, who has a doctorate in anthropology and post-doctorates in psychiatry and internal medicine, has helped hundreds of doctors deal with high levels of stress and the behaviors that it can produce.

Dr. Pfifferling notes that doctors tend to be perfectionists. "That's drilled into them as residents, fellows and medical students, and possibly by the family as well," he says. "They internalize that in some form as a way to judge what good medicine is, with potentially enormous stress consequences."

He notes that many individuals use coping mechanisms that have negative consequences for themselves and those around them. "Some cope by 'acting out,' turning their frustration and anger onto others via sarcasm, belittling, humiliation, cursing and so forth," he explains. "Some individuals cope by 'acting in,' stuffing their feelings inside, leading to burnout, fatigue and exhaustion. Others turn to alcohol or drugs."

|

Asked what separates individuals who act out from those who act in, Dr. Pfifferling says that people tend to model the behavior they were subjected to earlier in life. "If the people who taught you were controlling, threatening, deprecating or shaming, you may resort to that same behavior later when you're overwhelmed," he explains. "This may be learned from your family, of course, but medical training is often abusive in this same way."

Dr. Pfifferling says that individuals who cope by stuffing their anger and anxiety inside are often those who were sanctioned severely at some point for acting out. "This can lead to being burned out, emotionally exhausted and having compassion fatigue—i.e., having nothing left to give," he explains. "Those who suffer as a result include the doctor's families, friends, patients and staff."

Concrete Steps to Relieve Stress

Mr. Pinto says that stress mediation is crucial. "I ask doctors to describe their level of stress on a one-to-10 scale," he says. "The average doctor will say 'six or seven.' Then I ask about the level of stress mediation he or she is applying, including sleep, exercise, nutrition, recreation, a good relationship with your significant other and whatever do you do for religious or meditative practice.

"Clients usually say that they're mediating their stress at three or four or five," he continues, "either because they don't have time or haven't been conscious about the need to do this. My job is to help doctors decrease the amount of stress, increase the amount of mediation, or both, and help them learn to better recognize when things are getting out of balance."

Dr. Pfifferling often gives presentations summarizing basic steps any doctor can take to lower stress. His recommendations include:

• Enhance your coping skills. "Do some reading or take a class to increase your communication skills, conflict-management skills or time-management skills," he suggests.

• Take multiple, real vacations, both short and long. The recent ASCRS survey found that the majority of respondents take two to three weeks of vacation a year—or less. Almost 90 percent wish they could take several weeks more.

"Every doctor needs time for relaxation, pleasure, not thinking, and doing things that don't require medical skills," says Dr. Pfifferling. "Unfortunately, many doctors don't understand the power of sleep, restoration and vacation. They feel that they can't ever leave because they're so indispensable. So they go to a medical meeting and call it 'taking a vacation.' Or they take a week off and spend three days exhausted from what they had to do to get ready for vacation, one day being present and relaxed, and three days of anticipatory anxiety before they go back to work. That's not a vacation.

• They look at things in context. They don't believe they have to take everything seriously. • They have healthy self-esteem. If they're faced with disappointment or failure, they don't beat themselves up about it. • They have confidants. They have friends and colleagues with whom they can share the ups and downs of their lives. • They don't have to control everything. Whether because of faith or philosophy, they're willing to let go of things that are beyond reasonable management. They're willing to say, "Let's get a second opinion. Let's try tincture of time. Let's see what mother nature does." • Their ego is not attached to their success as a doctor. They see themselves as regular people who have medicine as their special interest. • They have the freedom to choose how to act in difficult situations. Stress-resilient individuals aren't stuck in automatic pilot where emotions and previous life experience are their main reactive resources. They have the ability to stop, take a breath and think through what their options are and what the short, medium and long-range consequences will be. • They have stress-management skills. They've learned strategies for communicating, managing their time, dealing with conflict and getting periodic rest and revitalization. |

"Taking multiple, real vacations is a huge stress reliever," he adds. "And you really don't want to look back someday and realize you never had a life."

• Make sure your intimate relationships are as cooperative, accommodating, collaborative and guilt-free as possible. Dr. Pfifferling recommends making a deliberate, conscious effort to leave your work at the office.

• Give the people around you timely, positive feedback on a regular basis. Dr. Pfifferling notes that doctors may not have received timely, positive feedback in their own lives or medical training, but omitting it is a form of abuse. Providing it, he says, removes a lot of dysfunction from your environment and can lower stress dramatically.

• Never pass up an opportunity to be at peace or at ease. "Give yourself permission to find these opportunities and take advantage of them," he says, "without guilt."

• Have a job exit strategy and contingency plan. "Sometimes a practice becomes a hostile, toxic environment, but many doctors will just assume that somehow it will get better," he observes. "If it doesn't get better despite your efforts, it's the wrong place for you and you need to do something about it."

• Say NO when requests are unrealistic or emotionally exhausting. Dr. Pfifferling says most doctors have a very hard time doing this because they want to please others and feel needed.

• Set realistic goals, and when you find yourself making headway, be your own best friend. "Think to yourself, 'Good for me,'" he says. "Don't wait for the rest of the world to give you positive feedback—the rest of the world doesn't really care. If you're dependent on others for approval, you'll always have low self-esteem."

Lowering Pressure in the Field

We asked several doctors to describe strategies they've employed to lower stress in their own practices.

• Don't overschedule your personal life. John S. Jarstad, MD, CEO of Evergreen Eye Centers Inc., in Washington state, says that in addition to his duties as CEO, he has served as chief of staff of the local hospital, board member and volunteer surgeon for a humanitarian organization, board member of a Boy Scouts council and leader of a local church congregation. Meanwhile, he's written a novel and been asked to coach high school teams, act as preceptor for pre-med students and be active in Kiwanis. "Things can get stretched pretty thin," he says. "It's not possible to live like that."

• Don't let your patients wait too long. "This is one of the best ways

to ruin my day," says Christopher J. Rapuano, MD., co-director of the cornea service and refractive surgery departments at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. "Most patients understand having to wait if an emergency comes up. But when it happens frequently, they become justifiably frustrated and occasionally quite angry, and I have a very hard time justifying it.

"To avoid this problem, I do two things. First, I try to keep the number of patients I see in a half day to a realistic number. While this means I sometimes have a slow day, it also means the overly busy days are few and far between. The decrease in stress is definitely worth a little less income.

"Second, I check my schedule a few days ahead of time, especially if I've been out of the office at a meeting or on vacation. If it's overbooked, I reschedule some patients to a less busy day or open up a half day to manage the overflow. It's worth it to avoid being yelled at by patients for not valuing their time."

• Choose the people you give your time to carefully. "I've been contacted by every possible stock broker, investment counselor, insurance agent, real estate investment firm and charitable organization," says Dr. Jarstad. "They all have a sweet deal they want to present to me over lunch or dinner. Our time is worth thousands of dollars per hour, and losing that time can add significantly to your stress level. Make sure what they're trying to sell you is worth it."

• Delegate handling employee grievances. "During my years as a group leader I'd often spend hours of my time each week handling employee grievances and interpersonal issues," says Amir I. Arbisser, MD, founder of Eye Surgeons Associates, P.C., with branches in Iowa and Illinois. "And without human resource management skills training in medical school or residency, hiring and firing was difficult and a source of considerable stress for me."

Dr. Arbisser found two ways to improve the situation. "First, I hired managers and gave them direct responsibility for teams of staff members," he explains. "For example, one manager is in charge of back clinical staff, including techs, nurses and scribes. Another manages non-clinical functions, including insurance, front desk, scheduling center and IT. We provide the managers with the opportunity to take courses to enhance their employee management skills, and I give them wide latitude in hiring, firing and disciplining—as long as matters are properly documented and policy is consistently applied. Employees have learned that I only intercede if the manager doesn't address their needs.

"Second, I enrolled our staff in a confidential employee-assistance program set up by a local hospital," he continues. "Interpersonal relationship problems (like family or spouse issues) are handled through the program, while professional office-related concerns are handled by the managers.

"The employee assistance program costs only a pittance per month, but it gives us a place to send employees with major personal issues," he says. "This has saved thousands of hours of my time and increased the productivity of the entire staff because employees aren't distracted managing each other's problems. Counseling takes place outside the office, and the hospital alerts us if a problem is potentially serious.

"The value of this has increased over the years as more health insurance companies eliminate mental health counseling benefits," he adds. "We've participated for more than 15 years."

• Consider curtailing borderline LASIK patients. Given the current risk of medical malpractice suits, Dr. Jarstad says that when any test comes back abnormal he reduces the risk of a lawsuit by getting a second opinion, or referring the patient to another surgeon who is considered to be an expert in the area of abnormality. "Ten years ago, who knew that pilots would sue for $5 million when they went from 20/400 to 20/15 without correction, but had mild haloes?" he asks.

• Minimize competition between professional partners. "Ophthalmologists are naturally competitive, and that can lead to stress when the practice begins to track surgical times, number of patients seen, etc.," says Dr. Arbisser.

"To minimize competition, I did two things," he explains. "First, I developed a unique professional compensation structure that deemphasizes straight production numbers as the basis of salaries. In brief, we divide group net income based on three equal factors: charges, days worked and patients encountered. This system provides a variety of incentives without fueling direct comparisons between salaries. It also reduces the income devaluation caused by programs like Medicaid, so no one is economically disincentivized to provide care because of income category.

"Second," he continues, "when tracking surgical times, complications and resource utilization, we aggregate data from a group of surgeons, average their performances and mask their individual identities on bar graphs. Only the individual surgeon ever learns which graph is his or hers. The natural competitive urge still kicks in because no one wants the worst time or least productivity. But it keeps matters depersonalized, and I strongly prefer docs who compete with themselves instead of their colleagues.

"The long-term result of these two strategies," he concludes, "has been an amazingly stable group of doctors who almost always make the right choices for our patients and the group, instead of worrying about their own bottom line."

• Hire surgeons who have additional skills. "Today it's not enough to have great surgeons on staff," observes Dr. Jarstad. "Hiring bright, energetic, hard-working partners and associates who have business savvy and communications skills in addition to great surgical skills will lower the stress level in your office dramatically."

Do What Counts: Take Action

Managing stress—finding the "sweet spot" at which stress is beneficial instead of harmful—can be a make-or-break issue for an ophthalmologist. "Practicing medicine is often about losing things," say Dr. Pfifferling. "Like your identity. Your membership in a family. Your relationship with your children. You say 'yes' too much—you give in to the unrealistic demands of clinical care. You end up not knowing your children, and they resent it. Then when you need them, they're not there."

Asked what the most important advice he can offer would be, Mr. Pinto says it's to take action. "Once you've recognized that you're out of balance, don't just shrug it off and assume that it's your fate to be 'amped out' for the rest of your career," he says. "Instead, take positive, practical, engineered steps to get back into balance, just as you would when taking care of a patient.

"There are very practical ways to do this," he continues. "It may be nothing more than delegating more of your problems to your administrator, accountant, attorney or consultant. Part of it may be to find time throughout the week to de-stress in whatever way is useful for you—a nap in the middle of the day, meditation, jogging in the morning. Or adopting healthier eating habits, losing a few pounds or addressing a health problem that's been festering for a while that has you worried.

"The opportunities for stress mediation are as diverse as the number of ophthalmologists out there," he concludes. "But it goes back to the old maxim: Physician, heal thyself. If you don't have the discipline to do it yourself, then you need to do the same thing your patients do, which is to go to a higher authority—someone who's more expert than you to help solve the problem. There's no dishonor in getting outside professional help."

|