People have always been fascinated and frightened by the promise and threat of the future. And now, with the rollercoaster ride of the economy and the unknown form health care may take in the United States in the coming years, ophthalmologists are thinking more about the future than ever before. In this article, experts who track the shifting patterns of practice and reimbursement discuss the challenges that await the ophthalmologist in private practice and how he or she can rise to meet them.

Working for a Hospital

The phenomenon of physicians abandoning their private practices in favor of becoming an employee of a hospital has become a megatrend in medicine. This has left many in ophthalmology wondering if that’s a route they may be forced to take in the future.

|

For the physician’s part, in addition to a steady income, the life of an employed physician feels less stressful and risky, says Bill Wallace, practice administrator of Wallace Eye Associates in Alexandria, La. “One thing we’re seeing as we recruit new physicians is that they want a more set schedule,” he says. “They don’t want to be on-call; they want to work 8 to 5. They want a more static income level rather than something that ebbs and flows based on patient load. Being an employed physician offers all these things.” However, Mr. Wallace says the devil is in the details. “You see these employed physicians getting big starting salaries but then, a few years down the road, the hospitals renegotiate these salaries. This is because once they get your business, they still have to continue to grow, and unless you can grow as a provider, they’re going to start looking for other physicians, and your value diminishes. At that point, though, the doctor’s already given up his private practice and has nothing else to go back to.”

One reason ophthalmologists likely won’t be employed by hospitals in large numbers is that there’s actually not much in it for the hospital. “A typical cardiologist generates about $2.4 million per year for a hospital in tests and admissions, while an ophthalmologist is one of the lowest revenue generators: under $800,000 per year,” says Dr. Rich. “On one hand, an ophthalmologist might say, ‘That’s too bad, because it would be nice to get rid of the hassles of running a business.’ But, on the other hand, the reality of it is with the huge deficit we have in this country, one of the first places the government is going to look for savings is that 44 percent more reimbursement that hospitals get. The government will question why it should pay 44 percent more for the same service just because a doctor’s employer is a hospital. When that extra reimbursement goes away, hospital physicians are probably going to see dramatic cuts in their payments, probably within the next five years.”

The Boomers Are Coming

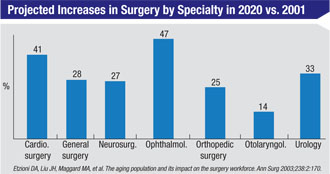

The first of the 76 million Americans born between 1946 and 1964, the baby-boom generation, turned 65 this year. This milestone represents the start of what will be a pronounced spike in the demand for all medical services, but especially the surgical services provided by ophthalmology. Experts say private ophthalmic practice will have to undergo some changes to accommodate the increased demand.

Jean Ramsey, MD, who practices in Boston and is the AAO Council’s co-chair on workforce needs in health-care reform, is trying to help future ophthalmologists manage the influx of patients. “America’s elderly population is expected to reach 72 million by 2030, more than double the number in 2000,” she says. “Consequently, age-related eye diseases, including cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration are expected to increase from 28 million in the United States in 2011 to 43 million by 2020. However, the number of U.S. ophthalmologists isn’t expected to increase over the next 20 years, and it’s expected that ophthalmologists will retire faster than the rate at which they’re being trained. In recent years, residency positions have been essentially flat, and the number of general ophthalmologists has decreased, while the number in subspecialties has increased.” And future ophthalmologists are attracted to subspecialties, too. “Since 1999 there’s been a steady increase in the percentage of [AAO] members in training who are interested in practicing at least 50 percent in a subspecialty: from 47 percent then to 71 percent now,” says Dr. Ramsey.

Ophthalmology could try to increase the number of ophthalmologists by increasing residency slots, but Dr. Ramsey says this isn’t an easy, or quick, solution. “First of all, this requires approval from many organizations, including the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education,” she says. “And even if slots were increased by 20 percent, it would take longer than 20 years to effect a 10-percent increase in the number of ophthalmologists.”

The other possible solution would be for current practices to increase their workloads. According to the most recent academy survey, most ophthalmologists are in favor of doing this, says Dr. Ramsey, but the effect might not be enough to meet the impending monstrous demand. The average increase cited was 30 percent. “So, some of the gap could be absorbed here, but clearly not all of it,” she says.

To help find possible ways to meet this growing demand efficiently, Dr. Ramsey cites the work of David Durfee, MD, the AAO’s senior secretary for ophthalmic practice. Dr. Durfee looked at various ways a practice could be structured and how that might allow the practice to deal with a greater volume of patients. “He found that physician-only practices can be very productive, with low labor costs and high levels of patient satisfaction,” says Dr. Ramsey. “However, the ophthalmologist in this practice will have a difficult time seeing more patients without adding more time or increasing the number of exam rooms. Ophthalmologists who have technicians can be efficient through strategic scheduling and they have a good patient flow. However, in that practice the ophthalmologist still needs to see every patient. An integrated eye-care delivery model, in contrast, brings together the Os, working as a team: ophthalmologists; optometrists; ophthalmic technicians and opticians. This model, Dr. Durfee found, can be very efficient, high-tech and cost-effective. In this model, each professional works in the area of care he’s licensed and trained for, in an atmosphere of mutual respect for the skills of each profession. Also, lower priority patients, such as those needing routine eye examinations, may not have to be seen by the ophthalmologist and consequently the care will cost less.”

R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, Bill Wallace’s father, founder of Wallace Eye Associates and chair of the cataract subcommittee at the AAO, says his practice uses a similar model, and it’s resulted in efficient, quality care.

“This model brings in qualified optometrists who are very capable of the patient care necessary for postop cataract and LASIK patients and, in some cases, preop care,” he says. “There are rules that stipulate when a surgeon needs to spend time with patients, especially preoperatively to perform proper informed consent and to do a personal eye exam; however, this is a more efficient model that keeps costs down. The future is going to demand that ophthalmology and optometry embrace each other.”

Ophthalmology may already be moving in this direction, says Dr. Ramsey. “According to the academy survey, while only 28 percent of ophthalmologists reported employing an optometrist in 1994, that number has been steadily rising, and it’s now 50 percent,” she says. “Further, 58 percent of young ophthalmologists, in practice for five years or less, employ an optometrist. The economic drivers for health-care reform seem headed in the direction of integrated care.”

Quality Will Be Job #1

In addition to seeing more patients, ophthalmologists will also be working in an environment where their outcomes, and the resources they use to achieve them, will be readily available for review by payors. Physician reimbursement can then be based upon this data.

“Today, your resource use for all your patients is being collected in the commercial and Medicare worlds,” says Dr. Rich. “In 2012, Medicare will send you a report on your resource use and compare it to that of your peers. So, if you’re an outlier, you’d better pay attention to that. Then, in the next year, they will publish your resource use publicly. For example, they’ll publish the fact that your resource use is 20 percent higher than average for cataract care compared to everyone else in Medicare, which might make you less attractive to an employer that has a select provider panel.

|

| R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, (right) discusses a LASIK treatment plan with Philip Carney Jr., OD. The entire eye-care team may have to do more in the future, say experts. |

Then, starting between 2015 and 2017, this data on quality and efficiency will be directly tied to reimbursement. “At that time, Medicare will be required to pay all physicians, in the fee-for-service part of Medicare, on the basis of quality and efficiency gains,” says Dr. Rich. “So, if you’re outside two standard deviations and have no quality, you get a big penalty in your payments the next year. If you achieve quality but do it inefficiently, you get a smaller penalty. And if you achieve quality and do so efficiently, you’ll get a nice bonus, above fee-for-service. This is a very powerful tool to make physicians look at their outcomes and the efficiency with which they attain them.”

Despite the challenges that await ophthalmologists in the future, Mr. Wallace believes opportunities will be there for private practitioners. “I’d encourage ophthalmologists to consider the traditional private practice model, as opposed to being employed by a hospital or medical system,” he says. “When you control all the variables in your office, you have a greater ability to maneuver when all these future changes come down. Having an ownership in an ambulatory surgical center will be essential, as it gives you income from the facility fee as well as the professional fee. And you’ll need control over the practice, because things like efficiency and volume will become more important.

“Be confident in the knowledge that you control a procedure, cataract surgery, and a scope of care that are important to medicine,” he continues. “There are going to be opportunities in this field, and for the foreseeable future I think that private practice will be a lucrative way to practice ophthalmology.”