In refractive surgery, as in life, the old saying still applies, "Be careful what you wish for—you may get it." With this in mind, surgeons wishing for microkeratome-free surgery may turn to surface ablation, but need to remember that complications can occur with PRK and LASEK, too. In this article, I'll share the methods I've developed for avoiding and managing complications over the course of almost 3,000 surface procedures.

Re-epithelialization

The size of the epithelial defect necessary to do PRK has become larger over the years, thanks to the use of larger ablation zones. While, in the past, the laser could be used to remove the epithelium out to 6.5 mm, we now use an epithelial brush or 20% alcohol to clear it to 8.5 or 9.0 mm. This means that, though PRK and LASEK have the benefit of larger ablations, both suffer from the same drawback when compared to LASIK: longer healing time.

For PRK, it takes three to four days for the epithelium to heal back beneath the bandage contact lens that's placed after the procedure. This can be delayed if patients lose the bandage lens, which results in the loss of the healed epithelium in PRK or the loss of the epithelial flap in LASEK. Be sure you have a lens that's a good fit for the patient; a lens that fits too loosely can delay re-epithelialization and is irritating, while one that's too tight can increase the risk of sterile infiltrates and conjunctival redness. Also, patients with an anterior basement membrane dystrophy or those sensitive to the preservatives used in the postop drops may take longer to heal, as well.

|

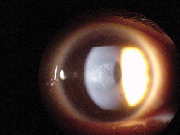

| This patient developed an infiltrate on postop day two, which progressed to S. aureus. He eventually needed a graft. |

For PRK patients, I believe that you need to see them pretty much every day after surgery until they re-epithelialize. Failing this, you can see them on days one and three, and then on the fourth day when you'll most likely be removing the contact lens. With LASEK, expect to leave the contact lens on a day longer. I'm a little more comfortable following LASEK patients less closely than PRK cases, because the former have an epithelial layer to protect the stromal bed.

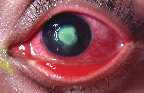

|

| The eye above after retreatment with mitomycin. The refraction is -1 D, and the haze is reduced to trace levels. |

Sterile infiltrates are usually small and tend to occur toward the periphery of the cornea, and are often not even in the ablation area. They're usually related to the bandage contact lens or associated lid disease (i.e., rosacea) as well as hypoxia if the contact lens is too tight. With them, you won't see an intraocular reaction and the patient will be only mildly uncomfortable.

|

| This patient developed an infiltrate on postop day two, which progressed to S. aureus. He eventually needed a graft. |

Infectious infiltrates tend to be larger, more centrally located, are associated with more discomfort and reaction in the anterior chamber than the sterile variety, and involve a larger defect. They also tend to be progressive, and increase in size with time. If you can't decide whether an infiltrate is infectious or not, get scrapings from the cornea, lids, conjunctiva and contact lens, a sample from the contact lens solutions, and samples of any drops the patient is using.

My current treatment for infectious infiltrates consists of a fluoroquinolone such as 0.3% ciprofloxacin (Ciloxan, Alcon) or 0.3% ofloxacin (Ocuflox, Allergan) every 15 minutes, decreasing the frequency to every half hour or hour after six hours.

If the organism is gram positive, I might add fortified cefazolin or vancomycin to the regimen, alternating with the ofloxacin or ciprofloxacin every 15 minutes, and, eventually, every hour.

The new fluoroquinolones moxi- and gatifloxacin are not currently approved for infectious keratitis, nor have they been approved in Canada where I practice. In theory, though, they could possibly be ideal for fighting infectious keratitis since they may face less bacterial resistance and give better

coverage of different organisms.

Haze and Regression

These two complications, usually going hand in hand, have been major concerns of surface procedures in the past. Though they can still occur in higher-diopter ablations, it's my feeling that their incidence has decreased markedly, thanks to better lasers, small-spot delivery systems and larger ablation zones that use smoother transition zones rather than jarring steps between the levels of ablated tissue.

In 2000, my colleagues and I looked at the outcomes of 365 PRK patients with myopia from -1 to -6 D. There were only three patients with 1+ haze at one year. This was a level of haze that was detectable but didn't affect vision. Then, when the patients were re-evaluated at 18 months, the haze had resolved and no patient had more than just trace levels.

| Table 1. Risks for Haze and Regression |

| high myopia |

| small ablation zones |

| oral contraceptive use |

| ultraviolet light |

| viral infection |

| trauma |

| surface disorders |

| irregular ablation beds |

| dark irides |

Some surgeons have also voiced concern over the entity known as late-onset haze. This is haze that occurs after three months, the time point at which normal postop haze is abating, and may coincide with the withdrawl of topical steroids.

Though the incidence of late-onset haze has been reported to be as high as 2 percent in patients with high myopia,1 I believe it rarely occurs now with new ablation techniques and LASEK. There haven't been any recent data released on late-onset haze, but I think the lack of papers on the subject indicates its decreased frequency. In fact, it's very difficult to prove there is any difference in haze levels between LASEK and PRK with today's techniques and lasers.

• Predisposing factors. Interestingly, high levels of myopia were once a contraindication to surface ablation. Now, however, with the threat of ectasia with LASIK if the surgeon removes too much tissue, some surgeons see higher levels of myopia as an indication for a tissue-conserving surface procedure.

It's important to aggressively treat surface disorders before the procedure to help reduce the risk of haze. Such disorders include allergy, dry eye, rosacea and blepharitis. I'll use doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d. for the rosacea and the dry eye, as well as ample amounts of artificial tears and even punctal plugs if necessary for moderate or severe dry eye. I'll treat blepharitis with a recommendation to the patient for good lid hygiene, as well as a prescription for topical erythromycin. I'll only perform the surgery when the cornea is clear following fluorescein or rose bengal staining. (See Table 1 on p. 54 for a list of risk factors for haze.)

Many of the risk factors in Table 1 were seen in the days of wide beam, small ablation diameter lasers and do not hold true today. One should be aware of these risk factors as well as be prepared to aggressively manage surface problems, however. To help reduce the risk of haze even further, it's important that the patients wear sunglasses and peaked hats whenever they're outside. This may be necessary for as long as a year postop. Also, taking high doses of vitamin A and E in the form of a capsule containing retinol palminate and 230 mg of alpha-tocopheryl nicotinate, t.i.d./30 days then b.i.d./two months may reduce the risk of haze and regression in patients with up to 10 D of preop myopia.2

• Mitomycin-C. Though higher levels of myopia are more likely to have a haze response after a surface procedure, I think the use of prophylactic mitomycin-C, though controversial, can go a long way toward reducing this risk in eyes -8 D and above. If a patient does develop haze, applying MMC to the stroma after epithelial removal will reverse it. This gives a sense of security that something effective can be done.

I will use MMC in patients with dark irides more frequently, since they've shown a higher incidence of haze and regression. If a patient were fair haired and blue eyed, for example, but around -8 D, I probably wouldn't use MMC, because I feel the light irides mitigate the risk for haze posed by higher myopia.

I use a solution of 0.02% MMC on a surgical sponge laid upon the corneal bed for about two minutes after the ablation. I then irrigate the entire area copiously.

• Haze and regression treatment. A two- to three-week course of steroids is the first step for a patient with haze and regression. Prednisolone acetate 1% q1h/2h is a good regimen. Along with this, observe the patient for any intraocular pressure spikes, since the corneal alteration may cause the IOP readings to be artificially low. It may be worth investing in a Tono-pen for the IOP measurements, since it allows you to measure the pressure outside the treatment area, which may provide a more reliable reading.

If the patient's regression and haze don't begin to resolve after a month, stop the steroids. If you notice improvement, though, you can begin to taper them.

You can successfully treat patients who have regression only or who have very little haze plus regression. For such cases, I'm now using wavefront-guided LASEK, or, if the epithelium is adherent, just removing the epithelium as in PRK before treating. In some cases, especially young patients, you'll want to overcorrect. If there's a lot of haze, however, the hazy stroma can ablate faster than normal cornea, so it's better to undercorrect.

If the patient regressed further than 1.5 D after his primary PRK procedure, I recommend using MMC after this ablation as I described earlier to stave off further haze and regression. Since the patient showed such an aggressive healing response to the first procedure, it's probably best to prescribe a three-month course of steroids that are to be tapered gradually.

If a patient develops such heavy haze that he's losing lines of vision, I'll first mechanically debride the epithelium, remove the scar with a 64 Beaver blade, then apply 0.02% MMC and irrigate the agent away. Re-epithelialization will be protected with a bandage contact lens just like the primary PRK, and the patient will have to use steroids for three to six months, tapering them toward the end of that period. This procedure will initially leave the patient with an undercorrection that I'll leave alone, since the refraction may improve as the scar heals. In rare cases, as I scrape the patient's eye, I can actually feel substantial scar tissue being removed. More often than not, these patients will then experience a substantial visual improvement immediately after the scraping, leading me to believe that I've actually removed a bit of scar tissue that was altering vision.

In most cases, though, after the haze resolves, I'll return after about six months and retreat. Some of these I'll retreat with LASIK in order to avoid the risk of haze, while in others a surface procedure may be necessary. With the latter, I again would use MMC postoperatively.

Overcorrections

High myopes are at greater risk for overcorrection, especially older patients. This is unfortunate, because older patients are the ones most sensitive to overcorrections. If you overcorrect a 25-year-old by 0.75 D, he'll be happy, because he can still accommodate and will actually have a little plus correction "in the bank" for when his myopia starts to progress. If you overcorrect a 55-year-old by 0.75 or 1 D, however, she'll be blurred at both distance and near, and will be unhappy.

The factors that can contribute to an overcorrection are many. Sometimes it's as simple as the humidity in the room, the corneal hydration or simply giving the person too much minus correction. Often, however, the overcorrection takes you by surprise and is due to that individual's healing response.

If a patient is overcorrected postop, in most cases you can just stop the postop steroids early and observe him. The refraction will usually come down over six months to around plano. Over the years, some surgeons have addressed overcorrections with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory such as Acular or Voltaren, followed by a bandage contact lens. This can actually help in older individuals, since, between the NSAID and the contact lens, something will stimulate a wound-healing response and the refraction will come down.

Though surface procedures can yield excellent outcomes, they're not without complications, and can pose some unique ones when compared to LASIK. However, with proper screening and aggressive treatment, the few complications that do occur can be managed successfully. As a result, you may not miss your microkeratome after all.

Dr. Jackson is professor and chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Ottawa, and is Director General of the University of Ottawa Eye Institute.

1. Lipshitz I, Loewenstein A, Varssano D, et al: Late onset corneal haze after photorefractive keratectomy for moderate and high myopia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:3:369-73:discussion 73-4.

2. Vetrugno M, Maino A, Cardia G, et al: A randomised, double masked, clinical trial of high dose vitamin A and vitamin E supplementation after photorefractive keratectomy. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:5:537-9.