New breakthroughs and information have arisen from all corners of the global medical community in the face of the novel coronavirus pandemic. Ophthalmic research has also played a part. The immunomodulatory research on cyclosporine and corneal transplants conducted by Mohammed Ziaei, MD, an ophthalmologist currently practicing in New Zealand, and his UK-based team in 2016, was recently cited by researchers in China studying potential interventions for coronavirus.1 “Cyclosporine can block the replication of the coronavirus,” Dr. Ziaei says. “[The researchers] used my article as a reference for its efficacy in organ transplants as well as a mechanism of action.”

The review article, published in the Journal of Medical Virology, states that “nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV played an important role in the process of virus particle assembly and release, and it might also bind to human cyclophilin A. Cyclophilin A is a key member of immunophilins acting as a cellular receptor for cyclosporine A. Cyclophilin A has played an important role in viral infection, either facilitating or inhibiting their replication. In addition, the inhibition of cyclophilins by cyclosporine A could block the replication of coronavirus of all genera, including SARS-CoV, as well as avian infectious bronchitis virus.”2

Plaquenil (hydroxycholoroquine sulfate) and Resochin (chloroquine phosphate) have also made a reappearance in the news as potential drugs for combatting coronavirus. Bayer recently donated three million chloroquine tablets for government research.3 Originally used to prevent or treat malaria, Plaquenil is now used to treat inflammatory diseases, such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Ophthalmologists conduct regular checks on these patients, since one rare side effect of the drug, when taken at high doses long-term, is retinal toxicity.

An interventional clinical trial in Shanghai, begun in February, investigated the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2.4 The study included 30 randomized participants, taking hydroxychloroquine 400 mg per day for five days, along with conventional treatments. Those with retinal disease were excluded from the study. The recommended dosing for Plaquenil is 6.5 mg/kg of body weight, with the maximum adult dosage at 400 mg daily. Results are pending.

Another recent study in China examined the antiviral activity and optimal dosing design for hydroxychloroquine for the coronavirus. The researchers propose that the immunomodulatory effect of hydroxychloroquine may be useful in controlling the cytokine storm that occurs late-phase in critically ill coronavirus patients. They found that hydroxycholoroquine was more potent than chloroquine for inhibiting SARS-CoV-2.5

New research is emerging rapidly. A March 16, 2020 study published in Bioscience Trends found chloroquine phosphate to have “apparent efficacy and acceptable safety against COVID-19-associated pneumonia” in multicenter clinical trials in China.6 A French study in a small number of patients found Plaquenil 200 mg three times daily for 10 days combined with azithromycin 500 mg for the first day, then 250 mg for four additional days to be effective in treating COVID-19.7

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine recently received FDA Emergency Use Authorization for treating coronavirus in teen and adult patients. This will allow the millions of doses of the drugs that have been donated by pharmaceutical companies to be added to the country’s stockpile. This may help patients who depend on

Plaquenil to control chronic conditions to continue to have access to the drug, rather than have to suffer from others hoarding it in an effort to treat potential cases of COVID-19.

1. Ziaei M, Ziaei F, Manzouri B. Systemic cyclosporine and corneal transplantation. Int Ophthalmol 2016;36:139-146.

2. Zhang L, Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. J Med Virol 2020;92;5:479-490. [ePub ahead of print]

3. @BayerUS. Tweet: 12:36 PM, March 19, 2020.

4. Lu H. Efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine for treatment of pneumonia caused by 2019-nCoV (HC-nCoV). NCT04261517.

5. Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis 2020. [ePub ahead of print]

6. Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of covid-19 associated pneumonia in clinial studies. Biosci Trends 2020;14:1:72-73.

7. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: Results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents; 20 Mar 2020 [Online ahead of print]

|

|

Update on Beovu

Novartis’ new anti-VEGF agent Beovu (brolucizumab), which received FDA approval in October 2019, is currently under a comprehensive product quality review after the American Society of Retina Specialists issued a warning to its members about several cases of inflammation associated with the administration of the drug.

Since its approval, more than 57,000 vials of Beovu have been distributed in U.S. clinics.1 Pravin Dugel, MD, presented to the Macula Society on the inflammation cases flagged by the ASRS. Findings included fifty-seven clinician-reported intraocular inflammation events, including nine cases with significant vision loss and five cases of retinal occlusive vasculitis, as evaluated by the Safety Review Committee (ongoing).2

“A vast majority of the patients had had previous injections, but it’s not clear to me how many of them were treatment-naïve for Beovu,” says Sunir Garg, MD, partner with Mid Atlantic Retina and co-director of the Retina Research Unit at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. “The mechanism of inflammation isn’t currently known either.”

In trials, the rate of inflammation was higher than what was seen with Lucentis and Eylea, says Rishi Singh, MD, a surgeon at the Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland Clinic, and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Lerner College of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio. “I think we were unaware that the inflammation was major or linked at all to the vascular occlusive events,” he says. “In previous phase III studies, we saw some small amount of inflammation present in early ranibizumab studies, so there was no concern. In light of some of the recent CEDAR and SEQUOIA studies, this was less significant.”

Novartis maintains that its data continue to support an overall favorable risk-benefit profile for the drug that remains consistent with or below the approved prescribing information. The prescribing leaflet states a 4 percent rate of intraocular inflammation and a 1 percent rate of retinal artery occlusion.

The rate, however, isn’t the issue, experts say. “The rate may very well be 4 percent, but it’s the severity of some of the cases that’s the issue,” says Dr. Garg. “If it were just mild iritis, then we could instruct the patient about what to look for and how to treat it, which is typically done with topical steroids over a short period time. The issue here is that, out of the 21 cases presented at the Macula Society, nine of them were thought to have profound or significant inflammation and seven of them lost at least five lines of vision. So it’s not the rate of inflammation, but the severity.

“The number of artery occlusions was also a little strange,” Dr. Garg continues. “One of the things we’ve struggled with for all of our drugs is whether or not the anti-VEGF drug itself increases the risk of thromboembolic events, such as a stroke, heart attack or artery occlusion in the retina. The problem we’ve run into is that patients with macular degeneration are older people, and older people get strokes, heart attacks and artery occlusions in the retina anyway. So if you do a study, a few patients will get artery occlusions and there’s some question about whether the artery occlusion rate is higher with this drug than with other ones, or whether it was just luck of the draw and it shook out that way.

“Our group published a study looking at the incidence of artery occlusions after intravitreal anti-VEGF injections,” he says. “We found a higher incidence of artery occlusions in macular degeneration versus vein occlusion, but we had under 50,000 injections, and when you’re looking at something so rare, it’s a little hard to say with great confidence that the injections themselves contributed to it. We had retinal artery occlusion in one out of 1,389 injections. Statistically, it’s a low incidence, but in totality with all the other things we’re seeing, it’s caused some concern among the retina community.”3

Dr. Garg himself hasn’t seen any cases like the adverse events reported in the post-marketing data for Beovu. He says his practice was slow to adopt Beovu and has done comparatively few Beovu injections since the commercial launch. In light of the ASRS announcement, he says, “I’m more hesitant to use Beovu until we have a better sense of what’s happening, why it’s happening, who’s at risk and what we can do to eliminate the chances of these occurrences.”

Dr. Singh says that since the announcement from the ASRS, “We discuss the most recent data on both uveitis and retinal vascular occlusive events with our patients. Even though the numbers are low, they appear to be higher than other market-available anti-VEGF cases. We give the patients the option of continuing on Beovu or switching back to their previous agent. About 50 percent of patients remain on the same course and another 50 percent switch back. Overall, I’m impressed with the drying ability and durability of Beovu in our patients.”

Novartis has suggested that patients who’ve had previous intraocular inflammation may be at higher risk for developing inflammation after Beovu. For continued use of Beovu, Dr. Garg recommends that surgeons be hesitant to use it in patients with a history of intraocular inflammation, particularly if they’ve had such inflammation after an anti-VEGF injection. “I would also be very hesitant to inject both eyes with Beovu at the same time,” he adds. “If I were to use Beovu in both eyes, I would try to get Beovu from different lots, and I’d definitely stagger the injections by several weeks. In one of the cases with severe inflammation, the patient presented a month after the most recent Beovu shot, but it wasn’t clear to me when the visual loss began. The patient may have experienced visual loss after a week and just showed up after a month.”

Dr. Garg points out that there are likely still some unreported cases of Beovu-associated inflammation that may have seemed like flukes—perhaps a lid infection. “Since the presentation at the Macula Society, doctors have been sharing a few of their cases,” he says. “But we don’t know the exact percentages or the incidence of significant visual loss in some of these patients.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Garg remains hopeful that Novartis and the retina community will get to the bottom of this. “Beovu has great value to our patients,” he says. “The results from HAWK and HARRIER were really encouraging, and we know that there’s a small but reasonable percent of patients who still have activity with our current anti-VEGF drugs. Their lesions continue to leak fluid and expand, and anecdotally, the patients that have switched from a previous drug to Beovu seem to have a good response. It’s definitely going to take some time until we can resume using Beovu with great confidence, but by sharing our experiences, sharing cases and staying transparent, we can figure this out.”

Dr. Garg and Dr. Singh have no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Novartis Press release

2. Screenshots of a presentation to the Macula Society by Pravin Dugel, MD, from Sunir Garg, MD.

3. Gao X, Borkar D, Obeid A, et al. Incidence of retinal artery occlusion following intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor injections. Acta Ophthalmologica 2019;e938-e939.

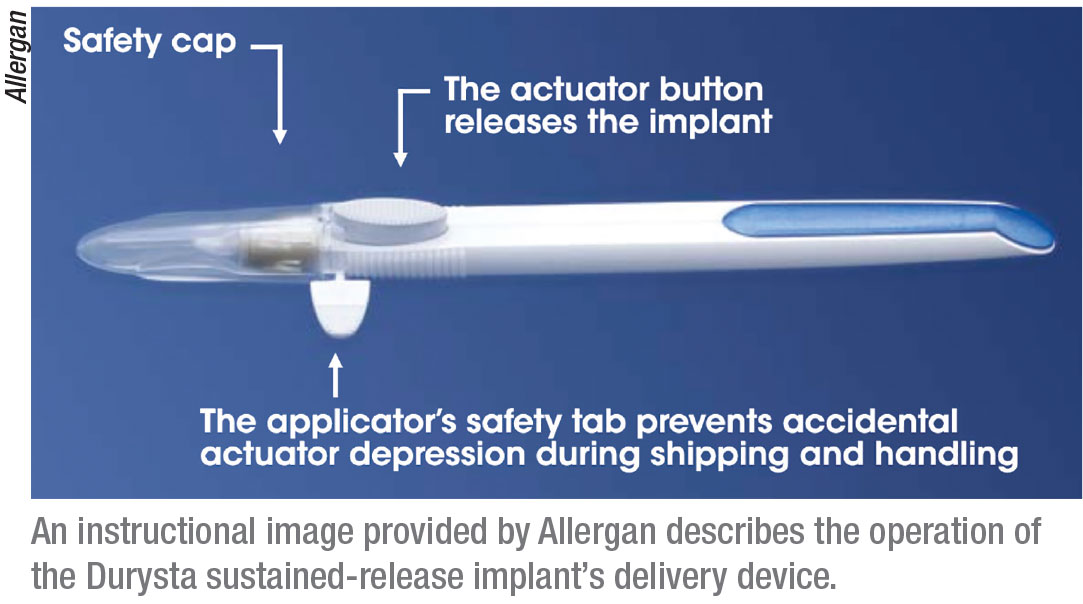

Sustained-Release Glaucoma Implant Approved

For the first time, American doctors treating glaucoma or ocular hypertension have access to a sustained-release implant that can offer many patients a way to lower their intraocular pressure without having to use drops—or at least with fewer drops. In early March the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Allergan’s Durysta implant, which contains 10 µg of bimatoprost, a prostaglandin analog. The implant comes preloaded into a single-use applicator that allows it to be injected directly into the anterior chamber. (The applicator must be refrigerated prior to use.) The drug is then slowly released over a period of 12 weeks—although data from the two clinical trials that led to approval suggest that its beneficial effects may extend beyond that time limit.

|

The implant’s efficacy was tested in two 20-month-long multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trials involving 1,122 patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension, with an eight-month-long follow-up period. (Subjects’ mean baseline IOP was 24.5 mmHg.) The implant’s efficacy was compared to that of twice-daily topical timolol 0.5% drops. In both trials, the implant reduced IOP about 30 percent from baseline (about 5 to 8 mmHg) over the 12-week period. (The FDA approval states that the implant shouldn’t be readministered to an eye that has previously had one, which would seem to undercut its utility.)

In the two clinical trials, 27 percent of patients experienced conjunctival hyperemia; 5 to 10 percent experienced such issues as foreign body sensation, eye pain and photophobia. The drug has also been reported to cause iris pigment changes in 1 to 5 percent of patients; those changes are likely to be permanent.

Felipe A. Medeiros, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology, director of clinical research and vice chair for technology at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, participated in the trials. “The procedure is straightforward and painless, and patients don’t feel anything once it’s in place,” he notes. “As far as side effects, in the Phase III clinical trials, most of those occurred within two days. Ocular adverse events such as discomfort and hyperemia were mostly due to the betadine used for sterilization during the procedure. Patients with a history of angle closure or active uveitis wouldn’t be good candidates; nor would those with a history of diseases that may affect corneal endothelial cells, such as Fuchs’.

“Patients are very enthusiastic about the idea of a sustained-release medication that provides long-term IOP control and potentially also improves the quality of IOP control—i.e., fewer peaks and fluctuations,” he continues. “Many patients have issues with adhering to topical medication protocols. The evidence in the literature points to more than half of glaucoma patients not being adherent. In addition, many patients have coexisting conditions that make it difficult to administer drops; they have to rely on their partners or relatives to administer them. Durysta may also help in these situations.”

Other possible benefits (or drawbacks) to this approach to treatment should become apparent as doctors use it. “In a preliminary post-hoc analysis from the Durysta Phase III clinical trials, we found that patients randomized to Durysta had slower rates of visual progression over time compared to those on timolol,” Dr. Medieros notes. “This may indicate a better control of IOP. We’re now collecting raw visual-field data from all of the sites that participated in these trials to conduct more extensive analyses of the data.” REVIEW