Making sure these issues don’t cause intraoperative or postoperative problems may require taking extra precautions; adding another surgery; changing your surgical technique; postponing the operation; or simply being extra vigilant about what you say to the patient preoperatively. Here, experienced cataract surgeons offer strategies that can help prevent unnecessary problems when cataract patients present with some of the most common co-existing conditions.

Corneal Pathology: The Exam

Corneal disease is one of the most common co-existing conditions that can interact negatively with cataract surgery. On the one hand, pre-existing corneal problems can affect the accuracy of IOL calculations and undercut quality of vision following cataract surgery; on the other hand, the cataract surgery itself can make some endothelial problems worse.

These strategies can help to ensure a positive outcome:

• Don’t forget to check for corneal issues preoperatively. “It’s important to make sure you know what you’re dealing with ahead of time,” notes Nick Mamalis, MD, professor of ophthalmology, director of ocular pathology and co-director of the Moran Eye Center’s Intermountain Ocular Research Center at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “If you’re contemplating doing cataract surgery on a patient, you need to do a thorough examination of the cornea.”

Vance Thompson, MD, founder of Vance

|

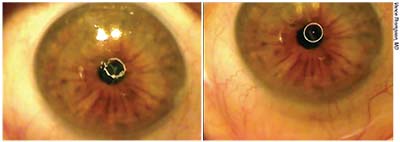

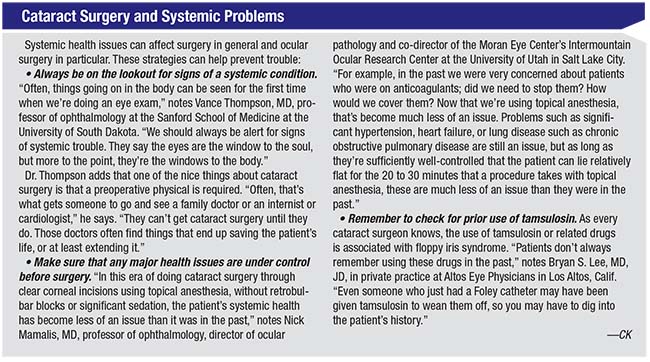

| Corneal problems should usually be addressed before performing cataract surgery. This patient had anterior basement membrane dystrophy but underwent cataract surgery without it being treated. After the cataract surgery, the patient was unhappy. Left: Before undergoing phototherapeutic keratectomy to address the ABMD, the reflection of the round illuminating light on the corneal surface is distorted, due to the rough corneal surface. Right: After epithelial scraping and lubricating drops the reflection is much smoother, just as the cornea will be after re-epithelialization and epithelial remodeling at about three months post-PK, resulting in much better vision. |

• If corneal or retinal pathology exists, do your best to quantify the amount of blur each problem is responsible for. Dr. Thompson says estimating the contribution of other problems besides the cataract is a key factor when preparing to do cataract surgery on a patient with corneal or retinal pathology. “In terms of the cornea, issues such as anterior basement membrane dystrophy, anterior stromal scars or Salzmann’s nodular degeneration can all affect best-corrected image quality,” he says. “Today we have wonderful diagnostics such as the HD Analyzer which can quantify an image-quality reduction caused by the anterior segment—the tear film, cornea and/or lens. We can also quantify the irregularity in the cornea by measuring topography, measuring the irregularity index with tomography and measuring corneal higher-order aberrations. We can quantify lens density with the Pentacam or use the iTrace to get an idea of how much of the blur is coming from the lens and how much is coming from the cornea.”

Of course, one of the main reasons to do this is to get the patient to understand that cataract surgery may not magically recreate the perfect vision of a younger person. “When explaining this to the patient, I still find it extremely helpful to simply grab the eye model or a white sheet of paper on a clipboard—with a nice dark felt-tipped pen, so that even a patient with blur can see what I’m drawing,” says Dr. Thompson. “I’ll explain that although the cataract is causing blur, we believe the retina and/or cornea are also causing blur, and we don’t know for certain which one is causing the most blur. Then I explain that we have to treat the part of the eye that we think is causing the most blur—if it’s treatable—and take the process in a stepwise fashion. Most important, these patients need to realize that they may not get everything they hoped for out of the cataract surgery.

“Patients are pretty smart,” he notes. “They appreciate the explanation of what’s going on inside their eyes, and the fact that you’re testing to make the best determination you can. I’ve had some patients say, ‘I think I’ll let my vision get a little bit worse, so I can maybe have a little more confidence that cataract surgery is going to help me.’ Mainly, it’s important for them to be making an informed decision.”

• Try using a gas-permeable contact lens to gauge how much any anterior corneal disease is contributing to reduced visual quality. “Even though I use all of this advanced technology, the tried-and-true test of putting on a gas-permeable contact lens to see how much irregularity it nullifies is extremely helpful when I have a patient with anterior corneal irregularities such as an elevated anterior stromal scar, Salzmann’s nodular degeneration or anterior basement membrane dystrophy—all of which are fairly common,” Dr. Thompson notes. “It even helps when the problem is dry-eye related.

“I may see a patient who’s 58 years old with both an early cataract and anterior stromal pathology who’s disappointed with his image quality,” he continues. “Perhaps his best-corrected spectacle vision is only 20/30. If I’m trying to determine whether the problem is the cataract or the cornea, I can put on a gas-permeable contact lens and suddenly the patient is seeing 20/20. That tells me that all, or almost all, of the blur is coming from the cornea. In that situation, I’m going to do a corneal surgery. On the other hand, if I put on a gas-permeable contact lens and he’s still only correctable to 20/30—and there’s no retinal problem—that tells me that the blur is being caused by the lens, and I’m going to do cataract surgery, assuming the patient is ready for a surgical procedure. If the result is somewhere in between, then I have to make a judgment call about whether to treat the lens or the cornea. Either way, I’ve found that performing an over-refraction with a gas-permeable contact lens is still very valuable, despite all of the advanced technology we have.”

Dr. Thompson notes that trying a gas-permeable contact lens won’t help an issue such as corneal edema or deeper corneal pathology. “Those issues, however, are likely to be revealed by testing with today’s instruments, or during the slit-lamp exam,” he says.

• If Fuchs’ dystrophy is an issue, perform additional testing. “One of the main corneal diseases that can affect cataract surgery—and be affected by cataract surgery—is Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy,” notes Dr. Mamalis. “If the patient has a history of Fuchs’ dystrophy, or you see guttata on examination, you should do specular microscopy and get an endothelial count to know what shape the cornea is in. If the patient has obvious corneal edema, you should also do pachymetry. The results can help guide you in terms of what you’re going to do in the surgery. If the cornea is more than 600 µm thick, for example, you may want to consider doing a combined procedure, performing a DSEK or other corneal endothelial procedure along with the phaco.”

Pathology & Surgical Options

Once you’ve evaluated the cornea, a number of factors need to be considered before proceeding with surgery:

• If the patient has corneal disease, determine whether it needs to be treated prior to cataract surgery. Bryan S. Lee, MD, JD, in private practice at Altos Eye Physicians in Los Altos, Calif., says that whether it’s worth trying to correct a corneal problem before proceeding with cataract surgery depends on a combination of factors. “You need to determine how bad the corneal pathology is, how much it’s independently affecting the patient’s vision, and how it affects the IOL calculations,” he says. “Another important consideration is the patient’s goals. How important is uncorrected vision for that person?

“I see a lot of Salzmann’s nodules,” Dr. Lee continues. “In many cases these have been ignored because they may not affect best-corrected vision much if the patient wears glasses. But at the time of cataract surgery, they can make it difficult to do appropriate IOL selection and can cause irregular astigmatism, which can definitely limit the IOL options. So if I find Salzmann’s nodules and see irregularity on the topography that’s potentially going to affect the patient’s vision or the IOL selection, I’ll do a superficial keratectomy and take them off first.

“It’s the same thing with pterygia,” he continues. “Some patients have a pterygium that’s relatively asymptomatic; they don’t have a lot of foreign body sensation or redness. It’s very stable. If that’s the case, sometimes you can do the cataract surgery and not do anything about the pterygium. But if a patient has some irregular astigmatism on the topography because of the pterygium or is highly motivated to have good uncorrected vision afterward, you may want to remove it. If so, you’ll need to give the cornea a couple of months to heal before you proceed with the cataract surgery.”

Dr. Thompson notes that minimizing corneal irregularities before proceeding with cataract surgery can make the keratometry measurements and implant calculations more accurate. “If you perform the cataract surgery based on implant calculations that were influenced by corneal pathology, and the patient isn’t happy with the image quality afterwards, then you’ll need to treat the cornea,” he points out. “At that point, the implant calculations you used will have been wrong for the eye the patient ends up with after you’ve treated the cornea. So, if the patient has a visually significant corneal problem, it’s much better to take care of it before the cataract surgery. Then, let it heal well before you take the implant measurements.”

• If the patient has Fuchs’, limit your IOL options accordingly. “In this situation, you’re not going to want to put in a presbyopia-correcting lens,” notes Dr. Lee. “You may not even want to put in a toric lens if you feel there’s a pretty high chance the patient may need a corneal transplant afterwards.”

• If the patient may eventually need a corneal transplant, take that into account when choosing your IOL power. “If there’s a good chance this patient’s cornea is going to decompensate, you’re going to need to do endothelial keratoplasty afterwards,” Dr. Lee points out. “You may want to shift your target a little more myopic to compensate for the shift that would happen with a transplant.”

Corneal Pathology: The Surgery

As noted earlier, your surgical plan may need to be altered to manage the corneal problem, or to prevent the cataract surgery from worsening it:

• If the patient has Fuchs’ dystrophy, adjust your surgical plan as necessary. “When dealing with Fuchs’ dystrophy, it’s a balance in terms of how bad the guttata are,” notes Dr. Lee. “If the patient’s symptoms appear to be caused as much by the cornea as by the cataract, we combine the cataract surgery with DMEK. If doing phaco alone, I use a dispersive viscoelastic and refill the anterior chamber with it more often. I also try to do the phaco as far away from the endothelium as possible.”

“Cancelling the cataract surgery in this situation is probably not necessary,” adds Dr. Mamalis. “As long as the corneal view is clear enough that you feel you can remove the cataract safely, I think you’re OK to proceed.”

• If the endothelium is fragile, change your OVD and lower your power level. “If you decide to proceed with cataract surgery in a patient with significant corneal endothelial disease, do everything you can to make the surgery as endothelium-friendly as possible,” says Dr. Mamalis. “Instead of using my standard OVD, I’ll use a

|

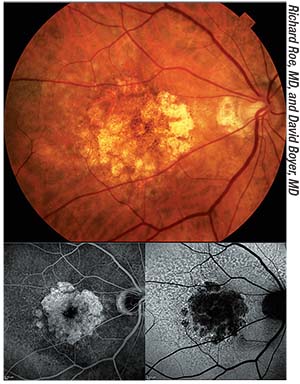

| A color fundus photograph of a patient with geographic atrophy, with corresponding fluorescein angiogram (bottom left) and autofluorescence (bottom right) images. Although controversy exists regarding whether cataract surgery exacerbates the progression of dry macular degeneration, most studies suggest that it does not. |

“These strategies would apply to any corneal endothelial disease,” he adds. “Fuchs’ is simply the most common.”

Retinal Pathology

If your cataract patient may have retinal pathology:

• Examine the macula before surgery and consider getting a macular OCT. “You may not be able to obtain an adequate view of the macula if you have a cataract that’s significant enough to affect the patient’s vision,” notes Dr. Mamalis. “However, you can get a very good OCT scan through a pretty dense cataract. That will allow you to know what’s going on in the macula. Macular OCT is very helpful for assessing the status of the macula and ruling out macular diseases, and there are some subtle macular diseases that are tough to see without an OCT scan, such as an epiretinal membrane.

“We’ve started to rely on macular OCT more and more,” he adds. “Our retina colleagues have started to recommend that we go ahead and do a preoperative macular OCT if there’s any question about the condition of the macula. I know of some surgeons who do macular OCTs on everybody, but I think we have to use our clinical judgment in this setting. However, if there’s any question, you want to be sure to rule out macular disease. A macular OCT prior to considering surgery is a good way to do that.”

• Consider altering the IOL options you offer when the retina is not pristine. “In a cataract surgery evaluation, everyone wants to know their options,” notes Dr. Thompson. “They wonder whether they should get a monofocal implant and wear glasses, or aim to replace both the clarity they lost and the reading ability they lost with one of the modern multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus lenses. Even though multifocals and EDOF lenses have been game changers, they still reduce contrast sensitivity somewhat, so if you put one of them in an eye that already has reduced contrast sensitivity, you’re likely to make the problem worse. For that reason, we usually lean towards an aspheric monofocal implant in a patient with macular issues.”

Dr. Mamalis agrees. “If your patient has significant macular disease or glaucoma with significant field loss, you really want to think seriously about whether that person is a good candidate for a multifocal lens,” he says. “Any lens that breaks up the image as it comes in has the potential to decrease contrast sensitivity. If the patient already has a diseased macula with diabetic macular edema/ischemia, epiretinal membranes or macular degeneration, or significant visual field changes from glaucoma, decreasing contrast sensitivity further may not be a good idea.”

Glaucoma

If your cataract patient also has glaucoma:

• Consider performing MIGS during the cataract surgery. “I offer this option to any patient who’s on a glaucoma drop with a definite diagnosis of glaucoma,” says Dr. Lee. “In this situation, cataract surgery is not only an opportunity to improve the patient’s vision but also to treat the glaucoma. I personally don’t do trabeculectomies or tubes, but I tell patients that with the new MIGS procedures we can get better control of your eye pressure and maybe get rid of one or two of your drops at the same time. There’s not much downside; some of these procedures can cause a little bleeding, but that’s usually pretty mild and self-controlled. You don’t have the risk of hypotony that you have with a trab or tube, and you don’t have a lifelong risk of endophthalmitis. This is a great opportunity to help a patient with mild to moderate glaucoma at the time of cataract surgery.”

• Consider altering your IOL options when the patient has glaucoma. “If a cataract patient has glaucoma, I generally

|

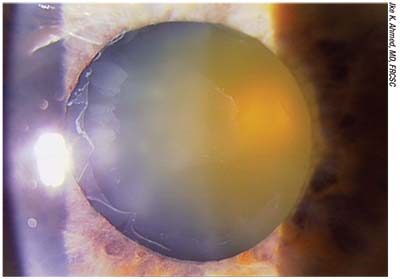

| Fibrillar material deposits on the anterior capsule that resemble a target are a sign of pseudoexfoliation. A cataract patient with pseudoexfoliation may have weak zonules, a potentially brittle capsule and pupils that don’t dilate well. These patients also need to be warned that there’s a risk of the need for additional surgery at some point in the future as a result of the lens possibly shifting or dislocating. |

I think it’s reasonable to put in the Symfony extended-depth-of-focus lens if someone has very mild glaucoma. It doesn’t reduce contrast sensitivity as much as a multifocal lens does.”

“If it’s well-controlled glaucoma and a very educated patient, and the patient’s glaucoma specialist feels OK about it, then we may consider offering the patient the option of an EDOF lens,” agrees Dr. Thompson. “Those lenses seem to reduce contrast sensitivity less than multifocality. But if the glaucoma is advanced, there’s no way we’re going to implant a multifocal or an EDOF lens. Furthermore, you have to keep in mind that even if a glaucoma patient doesn’t have reduced contrast sensitivity now, that may change in the future because glaucoma is progressive.”

• If the patient has pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, change your surgical technique accordingly. “Pseudoexfoliation requires using a different approach when performing cataract surgery,” says Dr. Mamalis. “In this patient you have potentially weak zonules, a potentially brittle capsule and pupils that don’t dilate well, so you have to be prepared to address these issues.”

Dr. Lee also warns these patients about possible postoperative problems. “I tell all these patients that there’s a risk later on—even much later on—of the lens shifting or dislocating,” he says. “That may require additional surgery.”

“The good news is that in both open-angle and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, very good studies have shown that just doing the cataract surgery itself will lower the intraocular pressure,” notes Dr. Mamalis. “Removing the large crystalline lens—and if there is exfoliation, removing the exfoliation material—can lower the IOP postoperatively without any change in glaucoma medications.”

• Beware of intraoperative and postoperative pressure spikes. “This is especially important if the glaucoma is moderate to advanced, where you find cupping, loss of nerve fiber layer and some visual field loss,” says Dr. Thompson. “In this situation we’re going to do everything we can to avoid large pressure fluctuations during the surgery. Furthermore, we need to think about the medications the patient will be on postoperatively, and we’re going to be very type-A about getting the viscoelastic out.”

Dr. Mamalis agrees. “Especially if a glaucoma patient has significant visual field loss, even a brief pressure spike could conceivably cause more vision loss,” he says. “That’s why you have to do everything you can to prevent that postoperative spike in pressure. Be sure to get all of the viscoelastic out and watch the postoperative pressure very carefully.”

Dr. Thompson adds that he likes to get a glaucoma specialist involved in these cases. “Even though we know that lens removal and replacement is a powerful glaucoma treatment by itself, it’s not unusual for a glaucoma specialist to also do a MIGS procedure during the cataract surgery,” he says. “That can help to blunt the possibility of a postoperative pressure rise, and may also help the patient get off drops.”

• If the patient has a pre-existing glaucoma tube shunt or a trabeculectomy, adjust your surgical plan as necessary. For an in-depth discussion of these issues, see the Glaucoma Management column on page 67.

Macular Degeneration

Macular degeneration is a common co-existing problem in older patients:

• When macular problems are present, make sure the patient’s expectations are realistic. “These patients may have tried every set of glasses and tear-film rehabilitation, and they see this as their last hope,” notes Dr. Thompson. “You have to make the patient understand that the cataract is indeed visually significant, but the macula also has significant problems. That means that the cataract surgery won’t solve all of the patient’s visual issues.”

He notes that the news isn’t all bad. “It would be very rare for cataract surgery not to help at all,” he points out. “It typically improves color perception, and since we know that both macular pathology and cataracts reduce contrast sensitivity, removing the cataract will typically improve that as well. So even though you may not improve Snellen vision in some patients, you can still increase their visual joy. They’ll see colors better and end up with improved contrast sensitivity.”

• Don’t withhold surgery because of dry macular degeneration. “Macular degeneration is very common in the elderly, which is the population that usually gets cataracts,” Dr. Mamalis points out. “There’s been some controversy about whether cataract surgery exacerbates the progress of dry macular degeneration. A few studies have indicated that it may do so, but most others have not. Some researchers have suggested that a few patients may already have a pre-existing subretinal neovascularization that wasn’t recognized, but is recognized after the surgery. However, if a patient doesn’t have subretinal neovascularization or leakage of blood or fluid, there’s no good evidence that cataract surgery will exacerbate the problem.

“Nevertheless, a thorough macular examination is important,” he notes. “Certainly you want to make sure that there’s no active subretinal neovascular leakage of blood or fluid prior to doing cataract surgery.”

• If you find active leakage of blood or fluid, work with your retina colleagues to address that before surgery. “A retina specialist will give injections of anti-VEGF medications to reduce or eliminate active leakage,” says Dr. Mamalis. “The retina doctor may also want to do an injection into the eye anywhere from a week to 10 days prior to the cataract surgery to make sure the surgery doesn’t exacerbate any neovascularization. This is a situation in which you want to coordinate your surgery with your retina colleagues, because the right timing can allow you to maximize the value of those injections for your surgery.”

Dr. Lee concurs. “Many of the retina specialists I work with want to do the injection about a week before the cataract surgery, but I leave it up to them,” he says. “I just want to make sure we’re all on the same page about the timing.”

• If macular degeneration is present, adjust the IOL options accordingly. “If I see drusen, I won’t put in a multifocal lens,” says Dr. Lee. “A toric lens is fine, unless the person has horrible visual potential. It’s difficult to come up with a clear rule regarding the extended-depth-of-focus Symfony lens; it depends on how mild the drusen are and how motivated the patient is. If the disease is really mild and the patient is motivated and really understands the risks and benefits, then I think you can put the Symfony lens in a patient with drusen. However, I would hesitate if the drusen start reaching the level of intermediate macular degeneration.”

Diabetic Retinopathy

If your cataract patient is diabetic and has developed retinopathy, these

|

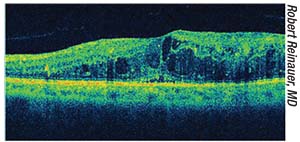

| Optical coherence tomography reveals macular edema. Performing cataract surgery can exacerbate macular edema related to diabetic retinopathy, so any edema should be treated prior to performing cataract surgery. |

• Be sure to address any macular edema or retinal neovascularization before proceeding with the cataract surgery. “Simply doing the cataract surgery can exacerbate diabetic macular edema,” Dr. Mamalis points out. “This is another situation in which doing something like a macular OCT preoperatively is very important. If you find macular edema, you should treat it prior to surgery and make sure the macula is dried out before you proceed. You also want to make sure there’s no obvious sign of neovascularization in the retina—on the disc or elsewhere—because the normal post-cataract inflammation and breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier can exacerbate that neovascularization.

“For these reasons, when performing cataract surgery on a diabetic patient, make sure that macular edema and any proliferative diabetic retinopathy are controlled prior to going ahead with the surgery,” he says. “This may mean postponing the surgery to give your retinal colleagues time to treat the retinal disease.”

Dr. Thompson agrees. “We’d prefer to do cataract surgery when the patient’s diabetes is under good control,” he says. “We often enlist the advice of the retinal specialist who’s taking care of their disease.”

• Make sure the patient understands how diabetic retinopathy may affect the visual outcome. “Explaining this to the patient up front will help to ensure that the patient has realistic expectations,” says Dr. Lee.

• If the patient is getting anti-VEGF injections for diabetic retinopathy, coordinate your schedule with the retina doctor. “This is similar to managing a cataract patient with macular degeneration,” notes Dr. Lee. “If the patient is getting regular injections from a retina specialist, be sure to coordinate the timing of the surgery with him or her.”

• Consider continuing postoperative NSAIDs for an extended period. “This patient population is at much higher risk for CME than the general population, even if they have no background changes and stable, treated disease,” notes Dr. Thompson. “With a healthy eye, we might have the patient use a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug postoperatively for a month, but with a diabetic patient we’ll use it for three or four months. It’s been proven to reduce the incidence of CME.”

Vitrectomy or Scleral Buckle

Strategies that can help prevent a poor outcome in these situations include:

• Be especially careful about your IOL calculations if the patient has a scleral buckle. “The presence of a scleral buckle really doesn’t change our surgical technique, but it can alter the patient’s axial length,” Dr. Mamalis points out. “It can make the calculation of IOL power more difficult, so you want to be very careful, especially if the patient is a high myope. You want to get the most accurate measurements you can when calculating the IOL power.”

• If the patient has had a vitrectomy, warn him ahead of time about the increased risk of a follow-up surgery. “Because the retina surgeon has to go through the pars plana, there’s usually at least a little bit of zonular loss as a result,” notes Dr. Lee. “I tell the patient to expect a higher risk of having a follow-up surgery after the initial cataract surgery, should I have any difficulty getting the cataract out. Depending on the patient’s vision and history, I also say the same thing I say in any situation involving weak zonules: Even if the surgery goes perfectly, there’s a chance that later on in life the lens could shift or move. I think a toric IOL is fine if the bag is stable, but you have to be careful with any presbyopia-correcting lens, given their history. That includes the Crystalens, because of the zonulopathy.”

• If the patient has had a vitrectomy, remember that the patient’s visual potential may still be unclear. “In this situation it may not be possible to determine the patient’s visual potential, depending on how quickly the cataract formed post-vitrectomy,” Dr. Lee points out. “I always remind patients that the retina is going to limit how good their vision is. I think patients understand that. On the other hand, if someone had enough time after the vitrectomy for vision to recover and become pretty good before the cataract developed, that’s reassuring in terms of the person’s retinal visual potential.”

• If a cataract develops very quickly after a vitrectomy, it’s possible there was damage to the posterior capsule. “Fortunately,” says Dr. Lee, “damage to the back of the capsule during a vitrectomy is very rare, and if it happens you can often see unusual changes in the posterior capsule and know to avoid hydrodissection.”

• If the patient has had a vitrectomy, remember that the capsular bag may move more during cataract surgery. “When the patient has had any prior retinal surgery, you want to examine the retina and make sure you don’t see any ongoing issues,” says Dr. Mamalis. “But if that surgery was a vitrectomy, you need to realize that it may change the dynamics of your cataract surgery. When you don’t have solid vitreous behind the lens, the capsular bag tends to move a little bit more during the surgery—to trampoline, if you will. Fortunately, several of the newer phaco machines have become very good at minimizing the amount of trampolining and movement of the capsular bag during surgery.”

|

“The lack of solid vitreous behind the capsule in combination with zonulopathy means that sometimes the capsule itself is a little floppy,” agrees Dr. Lee. “You want to make sure that you’re protecting the capsule with a second instrument. Also, sometimes you’ll need to fill the bag with viscoelastic more often, to try to keep the capsule pushed back.”

“A vitrectomy can also weaken the zonules,” adds Dr. Mamalis. “We’ve encountered cases that we thought would be just a routine cataract, and as we go in to begin the case we realize that the zonules are quite weak. You want to be sure that you have the ability to deal with this possibility. Have tools available that you can use during the surgery to support the capsular bag, such as capsular hooks and capsular tension rings, just in case.”

Retinal Vein Occlusion

A history of retinal vein occlusion is a sign that addressing other problems may need to be factored into your plans:

• If the patient has had an RVO, make sure he’s been evaluated for systemic problems. “A patient with this history should be evaluated for things like heart arrhythmias, carotid disease, hypertension, diabetes and other possible medical/systemic problems,” says Dr. Thompson. “When a patient has had an RVO, we need to consider the possibility the there’s something much bigger going on in the patient’s body that needs attention.”

• Make sure any macular edema is under control, and check for neovascularization. “Performing cataract surgery on a patient who’s had a retinal vein occlusion is similar to surgery on a diabetic patient,” says Dr. Mamalis. “If the patient has had a retinal vein occlusion—especially a central retinal vein occlusion—and there’s any macular edema associated with this, you want to make sure that the macula is dry and there’s no active edema at the time of the surgery.

“Patients who’ve had a central retinal vein occlusion may also develop anterior segment neovascularization as a result,” he adds. “For that reason you want to carefully evaluate the iris and the angle preoperatively. Make sure there’s no sign of neovascularization in either location.”

• Try to quantify the patient’s macular potential. “Sometimes this is not a lot different from working with a macular degeneration patient,” notes Dr. Thompson. “The patient may have chronic macular changes that can affect image quality. So in order to get a sense of how much the cataract surgery will actually do for the patient, it helps to know how much visual degradation is being caused by the retina and how much is attributable to the lens.”

• If the patient has had a retinal vein occlusion, enlist the help of a retinal specialist. “In this situation I always work with the input of a retinal specialist,” says Dr. Thompson. “I find that most retinal specialists are more conservative than most cataract surgeons. Also, I find that a conservative retina specialist can be very valuable in helping to educate the patient that cataract surgery may not improve vision that much. This can be a very important part of getting informed consent when a patient with something as significant as an RVO is pushing for cataract surgery.”

Keratoconus

How a patient has chosen to manage this disease should be considered when choosing an implant:

• If a patient has keratoconus and is happy wearing an RGP contact lens, avoid a toric implant. “Using a toric lens is technically off-label, but some keratoconus patients do really well with a toric lens,” notes Dr. Lee. “If you find consistent astigmatism measurements, I think a toric implant can be very beneficial. However, if you implant a toric lens, a rigid gas-permeable contact lens won’t be a good option for the patient postoperatively because it will eliminate any corneal astigmatism, leaving the patient with iatrogenic, lenticular astigmatism.

“The reason this may be an issue for some patients is that an RGP lens can provide clarity and sharpness of vision, and some patients really love that,” he continues. “I’ve had patients come in for a second opinion who were unhappy because they didn’t realize that they weren’t going to be able to wear an RGP contact lens anymore. Technically, they could, of course, but then they’d have to wear glasses to cancel out the IOL astigmatism. So if you’re planning cataract surgery on a keratoconus patient who loves the clarity and sharpness of RGP lenses, that person should get a standard monofocal lens. On the other hand, if it’s someone who mostly wears glasses or doesn’t really like RGPs, then I think a toric implant will work well.”

Setting Patient Expectations

Co-existing conditions can have a profound effect on intraoperative complications, visual outcomes and the possibility of needing further surgery down the road, making the patient’s expectations especially important. To minimize the chance of a very unhappy patient:

• Make sure the patient understands that this is not standard cataract surgery. “It’s really important to have a thorough informed consent conversation with the patient preoperatively,” notes Dr. Lee. “You want to make sure patients understand what’s different about their eye, and why you’re making the recommendations that you are for their surgery and IOL selection. The paper they sign isn’t really the issue—it’s the conversation you have, and making sure they understand.”

• Counsel patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy carefully before the surgery. “You have to let the patient know preoperatively that he may have delayed or extended healing time,” says Dr. Lee. “There’s a risk of corneal decompensation and the possibility of needing a corneal transplant afterward.”

Dr. Mamalis notes that without this counseling, the patient is likely to blame the surgeon for a less-than-ideal outcome. “If the cornea was not quite decompensated before surgery and the vision wasn’t too bad, these patients could still end up with corneal edema after your cataract surgery,” he says. “If they do, they’re going to blame you—you caused it. So you need to counsel these patients ahead of time that there’s a good chance they’ll need further surgery such as DSEK later to replace endothelial cells.”

• Make sure the patient understands that managing multiple problems can take much longer than simply having cataract surgery. “When a patient has two sources of visual limitation—and some may even have three—corneal, lens and macular pathology—it’s important to educate the patient that dealing with these issues is going to be a stepwise process that takes much more time than cataract surgery alone,” notes Dr. Thompson. “A patient might have a fair amount of corneal pathology, such as Salzmann’s nodular degeneration from contact lens wear, or a thickened, hypertrophic peripheral cornea. In that situation, I’d want to address the corneal problem first. If it’s visually significant anterior corneal pathology, I’d want to do a corneal scraping or a lamellar dissection, or a diamond burr smoothing, or a phototherapeutic keratectomy to smooth out the cornea, because often that will eliminate a lot of visual irregularity. Then, the patient may not even feel the need to have cataract surgery. However, you have to make it clear to the patient up front that instead of waiting a month to get new glasses after having nothing but cataract surgery, this could become a six- to nine-month journey if we go after the corneal pathology first and let things heal well, and then reassess the patient’s vision.”

• When you discuss these issues with the patient preoperatively, try to have a loved one in the room as well. “That’s important because this discussion can become sensory overload,” explains Dr. Thompson. “The patient may not remember everything you said if he’s the only person in the room with you. So ideally, you should have a second set of ears.”

• Be sure to note in the chart that you discussed these issues with the patient preoperatively. “You should be very specific in your medical record about what you found in your exam, and describe what you discussed with the patient as far as how the different parts of the eye may be contributing to reduced vision potential,” says Dr. Thompson.

Dr. Mamalis agrees. “I’ll often write ‘Discussed guarded prognosis

|

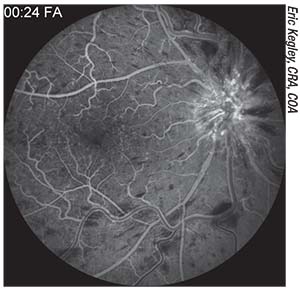

| Fluorescein angiography showing a central retinal vein occlusion. A patient with this history should be evaluated for possible medical/systemic problems. Then, before cataract surgery, make sure the macula is dry with no active edema and carefully evaluate the iris and the angle to ensure there’s no sign of neovascularization. |

Dr. Mamalis adds that it shouldn’t be necessary to alter your informed consent document. “The informed consent should pretty much have everything in there already,” he says.

• If you use electronic medical records, consider giving the patient a printout that includes the mention of your preoperative discussion. “With EMR we can give the patient a copy of what we said during the examination,” says Dr. Mamalis. “We include the sentence that says we discussed the guarded prognosis with the patient.”

Some Final Thoughts

In terms of the big picture, a few strategies are worth keeping in mind:

• Always do a thorough preoperative evaluation of the patient. “This is the most important thing,” says Dr. Mamalis. “I know that in a busy clinic it’s very difficult to make sure everything gets done, but when you’re going to operate on a patient you need to get a thorough history and do a thorough examination. It’s critical, because you want to know what you’re dealing with ahead of time. You don’t want any surprises when you’re in the middle of surgery—or immediately after surgery.”

• Plan ahead. “Whatever co-existing condition you’re faced with, you want to have thought about it and planned for it before you do the surgery,” Dr. Lee points out. “You shouldn’t have to be solving foreseeable problems in the middle of a stressful situation when things are not going as planned in the OR. Think through the possibilities in a more controlled environment.”

• Accept that sometimes you’ll have to tell the patient you can’t do what he’s requesting. “Today, cataract surgery is so successful, and we’re so used to being able to meet and exceed patients’ expectations, that it can be difficult to have to tell a patient that something is not a good idea,” observes Dr. Lee. “However, that’s our job as the physician.” REVIEW

Drs. Lee, Mamalis and Thompson have no relevant financial ties to any product mentioned.