Ophthalmologists are no strangers to the classic red eye presentation, which tends to rear its head in the clinic on a daily or weekly basis. Typical causes include conjunctivitis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, dry eye, blepharitis, topical glaucoma medications and contact lens overwear. The full list of red-eye differentials is vast, however.

Here, experts share some tips for narrowing down the cause, as well as some of the more unusual culprits behind red eye.

Patient Symptoms

Asking patients about any associated symptoms is a key step toward determining the underlying cause of red eye. “I usually ask patients if they’re having any irritation, pain, discharge, light sensitivity or foreign body sensation,” says Masako Chen, MD, an assistant professor of ophthalmology and director of Comprehensive Eye Services at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai. “If I’m suspicious for some of the more unusual causes of red eye, I might also ask certain patients about recent sun exposure or contact with sick people, topical and systemic medication use, history of past eye or other infections, and history of skin lesions or skin cancer removal.”

“If patients report symptoms such as redness, some irritation, dryness and foreign body sensation that have been occurring on and off for a long time, that makes me think of a dry-eye situation,” says Sezen Karakus, MD, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “But, if they mention pain, light sensitivity, difficulty opening the eyes or decreasing vision, those are red flags that something more serious may be going on.”

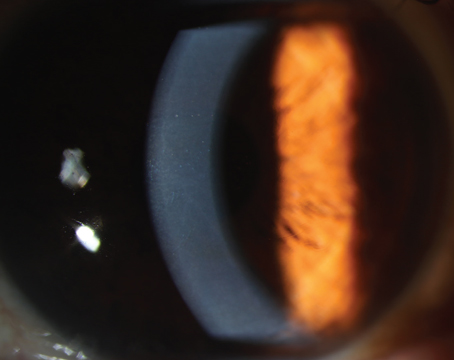

|

| A patient with herpes simplex keratitis presented with a geographic ulcer, patchy corneal opacities and diffuse conjunctival injection. In the second photograph, ulcer area is visualized using fluorescein dye under cobalt blue light. (Courtesy Sezen Karakus, MD) |

A Thorough Examination

Simple symptoms can sometimes mean serious disease. Dr. Karakus says it’s very important to carry out a thorough comprehensive exam for red-eye patients. “Some of the issues causing surface diseases may affect the corneal nerves as well,” she says, “and in those cases, patients may not have significant pain or discomfort, but their vision may change.”

Here are some points to keep in mind during the exam:

• Observe the patient. “The exam begins the second you walk into the room and see the patient,” says Bennie H. Jeng, MD, chair of the ophthalmology department and director of the Scheie Eye Institute at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia. “In addition to the eyes themselves, look at the eyelids and the face. See what the patient’s reaction is when the lights are on. If they have photophobia, that may point you to something else. When looking at the eyelids, note their position. Is there any malposition that might be causing exposure that then causes red eye?”

When examining the eyelids and face, Dr. Karakus says she checks for any signs of active skin disease such as rosacea, eczema or other inflammatory skin diseases that could contribute to red eye.

• Look with the lights on. “Looking with the lights on is important because sometimes red eyes will appear differently under different lighting,” says Dr. Jeng. “With scleritis, for example, the quality of the redness and inflammation is different when you look at it without the slit lamp under room lighting.”

• Be methodical and consistent. “During the exam, go carefully from front to back,” says Dr. Chen. “Make sure there’s no scarring, blepharitis or meibomian gland disease. Look at the palpebral conjunctiva to ensure there aren’t any tumors, foreign bodies, follicles, papillae, symblepharon or other abnormalities. Examine the cornea to ensure there are no infiltrates or ulcers, and check for anterior chamber cells to rule out anterior uveitis. Depending how the exam goes, you may choose to dilate the patient for a fundus exam. I tend not to dilate patients with viral conjunctivitis to make sure I don’t infect my equipment.”

• Always flip the lids. When checking the conjunctiva, it’s important to pull the lower lid out and flip the upper eyelid to check for abnormalities such as foreign body, follicles, papillae or symblepharon. “Follicles or papillae are signs of a certain type of inflammation with allergic or infectious causes,” Dr. Karakus says. “Also check for scarring, because that could indicate more serious problems.”

“A foreign body in the eye is an unusual cause of chronic conjunctivitis,” says Dr. Jeng. “A contact lens may be stuck in the upper fornix, or sutures may have eroded from underneath the conjunctiva.”

• Stain the eye for additional clues. “When checking for corneal and conjunctival abnormalities, we use vital dyes to identify areas with more dryness or inflammation or anything abnormal,” Dr. Karakus says. “With those vital dyes, we can see which parts of the eye are particularly affected by the disease. This could give us a clue as to whether the red eye results from underlying autoimmune disease or is a nerve-related issue, for example. It may also be toxicity from certain eyedrops or environmental exposure. If the lower part of the cornea is dry, then that might indicate a lid margin-related disease such as blepharitis or meibomian gland dysfunction.”

• Check for abnormal color. “If the eye isn’t a normal color or the cornea has a gray or white spot, this may indicate a more serious inflammatory cause or infection,” Dr. Karakus continues. “There may be other findings within the cornea such as edema or irregularities. From there, you’d go through the differentials.”

• Check for abnormal vasculature. More serious causes of red eye, including keratitis, iritis or scleritis, often present with abnormal vasculature. “Ocular surface squamous neoplasia often presents with abnormal corkscrew vessels,” adds Dr. Chen. “Dilated and large vessels may mean you need to do gonioscopy to look for tumors, masses or iris lesions.”

• Ask about “redness relief” drops. “Patients don’t like the appearance of red eye,” says Vatinee Y. Bunya, MD, MSCE, co-director of the Penn Dry Eye and Ocular Surface Center of Scheie Eye Institute in Philadelphia. “I always tell patients that there’s a danger of rebound redness if vasoconstrictors (e.g., naphazoline) are used chronically and then stopped. The eyes may appear redder than before. For special occasions, such as a wedding or a big meeting, using an anti-redness drop such as Lumify (brimonidine tartrate) is okay, but like vasoconstrictors, it shouldn’t be used long-term. It’s best to treat the root cause of the red eye, rather than mask it.”

Dr. Bunya says that it’s possible these drops could make it more difficult to tell what’s going on since the patient may feel okay and their eyes don’t look visibly red. However, “more serious causes will have signs other than a red eye, ” she says. “Lumify won’t help with light sensitivity or a bad infection.”

• Bring the patient back sooner. If the patient history doesn’t fit the exam, don’t be afraid to rethink the diagnosis, especially if the patient isn’t getting better. “Chlamydia, for example, can cause a chronic conjunctivitis that doesn’t respond to treatment and can last several weeks,” Dr. Bunya says. “If I’m not 100-percent sure about the diagnosis, I’ll bring the patient back a bit sooner. Most times, if you see the patient back again, the diagnosis will become obvious. I always tell patients to call immediately if they experience any warning signs such as decreased vision or worsening pain—basically if they aren’t responding to the treatment plan.”

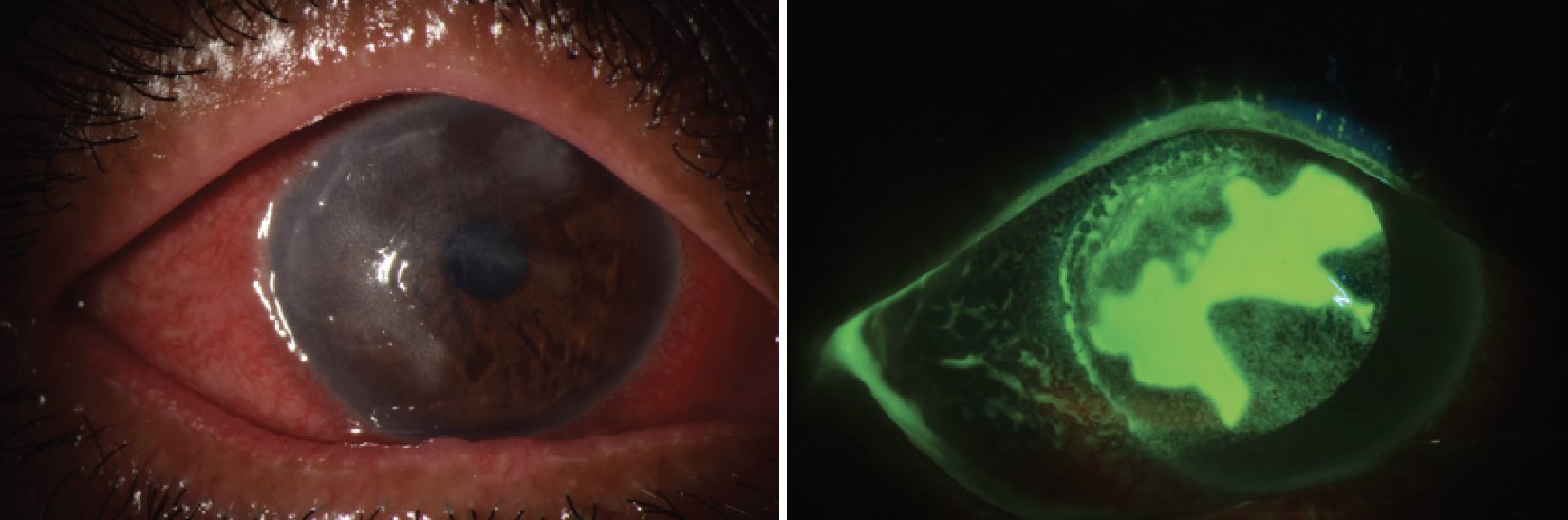

|

| A patient with superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, showing injection of the superior bulbar conjunctiva with engorgement of vertically-oriented blood vessels. In the second photograph, the affected area is visualized with lissamine green staining. SLK is an inflammation of the superior bulbar conjunctiva along with the adjacent limbus and corneal epithelium. (Courtesy Sezen Karakus, MD) |

Chemical Burn

Among the less run-of-the-mill reasons behind red eye are chemical burns. Chemical burns often result from household cleaning agents and medications. Fortunately, Dr. Karakus says, “It’s often obvious when a chemical was involved because the patient is usually able to tell you about an incident, the type of chemical and which areas were exposed.

“Sometimes only part of the eye is affected, and other times the whole conjunctiva appears severely inflamed,” she continues. “Abrasions or ulcers of the cornea or conjunctiva may also be present. Chemical burns often cause inflammation in the limbus.”

Mild burns are usually treated with topical steroids and lubricants. If epithelial defects are present, prophylactic antibiotics may be used.

Photokeratitis

“When you see diffuse corneal staining, that’s usually an indication of some form of toxicity from something in the air, preservatives in eyedrops or even ultraviolet light,” says Dr. Karakus. “Many patients aren’t aware of the damage from UV-light exposure until they start having symptoms.”

Careful questioning about activities or recent trips can help pinpoint the cause. Dr. Karakus says UV-sterilization devices that aren’t properly covered while in use are often the culprits behind this form of keratitis, but highly reflective surfaces can also cause UV-induced keratitis. “I once had a patient who went skiing without goggles on, and the sunlight reflecting off the snow caused a diffuse keratitis,” she says.

A case of nightclub photokeratitis was described in which a 30-year-old nightclub technician reported working with intense ultraviolet lights for six hours before experiencing symptoms.1 He had severe conjunctival injection and corneal punctate epithelial erosions, and was treated with oral analgesics, timolol, lubricant eyedrops and antibiotic prophylaxis. At one week his corneas were clear, BCVA was 20/20 (from 20/30 OD and 20/40 OS) and IOP was 12 mmHg OU.

Anterior Uveitis

“Anterior uveitis is differentiated from more common causes of red eye such as conjunctivitis by the presence of inflammation and accumulated white blood cells in the anterior chamber,” Dr. Karakus says. “Patients often have pronounced limbal flush.”

Other signs may include keratic precipitates, hypopyon and iris nodules. Patients usually report symptoms of rapid-onset pain, redness and photophobia. A thorough medical history can provide further clues, as anterior uveitis often arises from illness, a virus or an associated underlying disease. Ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis are risk factors. Acute anterior uveitis resolves with anti-inflammatory therapy.

Dr. Chen notes that “there was a case that was initially diagnosed as bilateral conjunctivitis, but on the anterior segment examination, there were a lot of cells, and no follicles or papillae on the eyelids. The patient was diagnosed with bilateral anterior uveitis and further bloodwork confirmed tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU).”

Acute Angle Closure

One of the more unusual and serious causes of a red eye is acute angle closure glaucoma, where outflow pathways are obstructed, often by ocular trauma. “Patients have acute onset of redness and sometimes light sensitivity,” says Dr. Bunya. “They may have blurred vision because the cornea is edematous from the acute rise in pressure. At the slit lamp, the anterior chamber will appear narrower. Pressures will be high.

“Any time a patient has any sort of acute vision loss or severe pain, that puts them in a different category of urgency than someone who comes in with no changes in vision and little pain,” she explains.

Intraocular pressure-lowering treatment should be initiated as a first-line treatment for acute angle closure.

Episcleritis & Scleritis

Episcleritis and scleritis may be idiopathic or arise from associated systemic conditions, but scleritis is more frequently associated with underlying systemic disease, particularly rheumatologic conditions.

“Scleritis affects the deeper vessels and has more of a radial pattern than the articulated network that you’d normally see with either episcleritis or conjunctivitis,” says Dr. Jeng. “Both episcleritis and scleritis can be localized, in contrast with conjunctivitis which generally affects the entire conjunctiva.”

Patients with episcleritis are usually asymptomatic. “Episcleritis isn’t as disruptive a disease, so supportive therapy such as lubrication is often all that’s needed,” Dr. Jeng says. “If the patient is bothered by it, a low-dose mild steroid can sometimes work.

“Scleritis, on the other hand, requires treatment,” he continues. “I don’t generally find that topical drops are all that effective. Scleritis patients usually need to be treated systemically. First, identify and treat the underlying disease. That will usually treat the scleritis. If the patient doesn’t have an underlying disease associated with the scleritis, I’ll usually go with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory to treat the inflammation.”

Herpes Simplex

Primary herpes simplex virus ocular disease is often mistaken for conjunctivitis. It may manifest with unilateral follicular conjunctivitis. Common symptoms include eye redness, pain, light sensitivity, watery eyes and eyelid inflammation. Reactivation of the disease may be triggered by stress, sun exposure, fever or certain medications. It’s important to identify and treat herpes infections promptly with antivirals.

“Be careful about prescribing steroids to patients without seeing them,” Dr. Bunya points out. “I recently had a patient whom I followed for years for dry eye and other chronic eye problems. She called, asking if I could call in some steroid drops for what she thought was a typical flare-up, but I said, ‘It’s better if you come in so I can take a quick look.’ It turned out that she had a herpes simplex infection of the cornea. If I had prescribed steroids without seeing her, her herpes infection would have worsened.”

OSSN

Experts say that though it’s rare, ocular surface squamous neoplasia should remain on clinicians’ radar when evaluating red-eye patients, as OSSN may masquerade as chronic conjunctivitis.

“Ocular cancers should always be in our differential, especially if the patient isn’t responding to treatment,” Dr. Karakus says. “If there’s a lesion, you’ll usually see it either within the conjunctiva or growing over the cornea. It’s very important to check the undersides of the eyelids—flip the upper lid and look inside the lower lid. You’ll see signs such as a lesion or bumps and lumps. Sometimes there may be follicular conjunctivitis, which would make you think of a second infectious cause or some other chronic inflammation. But if the patient isn’t improving with standard treatment, always consider OSSN.”

Treatment depends on the size of the lesion and what you’re suspicious for. “For an ocular surface tumor such as a small squamous cell, we generally do an excisional biopsy with cryotherapy and take the whole thing, and then check for margins on pathology,” says Dr. Jeng. “If it’s large, an incisional biopsy can be done for diagnosis, and then it may be treated using topical chemotherapy drops. Optical coherence tomography is sometimes used to diagnose the type of tumor and treat it without getting a biopsy.”

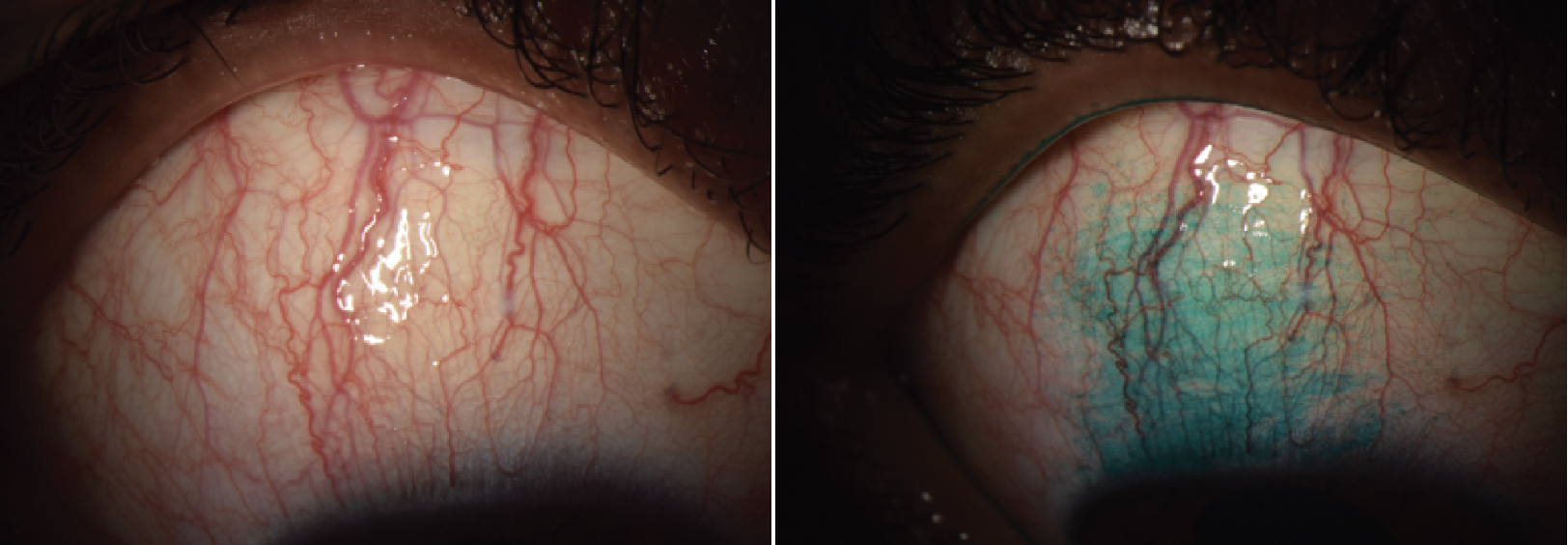

Conjunctivochalasis

With decreases in collagen, older patients may experience a red-orange eye from conjunctivochalasis. “Conjunctivochalasis isn’t usually recognized early on, and patients are often given only artificial tears,” Dr. Karakus says. “The condition may also result from chronic inflammation of the eyes due to conditions such as prior thyroid eye disease, ocular rosacea, dry eye or chronic eye allergies.”

It’s important to differentiate this condition from conjunctivitis and lid malposition disorders such as floppy eyelid syndrome. “Every time the patient blinks, the loose conjunctival folds that develop cause irritation, redness and more inflammation,” she says. “Patients experience irritation, pain, discomfort and fluctuating vision problems.”

Lubricants can relieve mild symptoms, but topical corticosteroids are sometimes needed to help reduce inflammation. In some cases, approaches to tighten redundant conjunctiva are employed, such as cauterization, conjunctival excision or scleral fixation.

“It’s worthwhile to mention that superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis will present with more pronounced redness under the upper lid in the bulbar conjunctiva,” Dr. Karakus adds. “Sometimes the conjunctiva will bunch in that area, creating friction. SLK is also associated with thyroid diseases.”

“As long as you have the differentials in your head and do a thorough anterior segment exam, you’ll get to the right diagnosis,” says Dr. Chen. “Take a really thorough history. If the history doesn’t fit with the exam, investigate further. Be methodical about the exam and go from the front to back in a consistent manner, and don’t skip any steps. Always flip the lid."

Drs. Jeng, Chen, Karakus and Bunya have no related financial disclosures.

1. Singh RB, Thakur S. Nightclub photokeratitis. Ophthalmology 2020;127:2:239.