Fortunately, childhood glaucoma is relatively rare. However, that means that the average ophthalmologist doesn’t see many young glaucoma patients. As a result, when a parent brings an infant or toddler in for an exam, many ophthalmologists react with trepidation; they may feel ill-equipped to manage the unique challenges of this situation. In my practice, however, we frequently manage young glaucoma patients. With that in mind, I’d like to offer some strategies you can use to most effectively help a family dealing with childhood glaucoma.

When seeing a new young patient, it’s helpful to think in terms of broad age groups, with each group requiring a different approach. One set of strategies works well with infants; another is most effective with toddlers and preschoolers; and a third approach works best with school-age children. Let’s consider each age group separately.

Examining an Infant

The youngest patients are the ones doctors tend to find most daunting, but there are a variety of strategies that work well with them. For example:

• Start by examining the infant from a distance. Don’t be in a hurry; you don’t want to jump into the child’s face and do an aggressive examination. It’s far better to begin by just looking at the child from a few feet away, which can reveal a lot. For example, when is the child keeping his eyes open? How is he using his eyes? Do the eyes look grossly normal? Is the child light-sensitive? Do the corneas look clear? Are the corneas enlarged? This approach is helpful for all three age groups, but it’s especially helpful when dealing with infants.

The size of the eye is a key issue, because when an infant has glaucoma, the eyes get bigger. Frequently they have corneal edema, although I’ve found that this occurs most commonly in the first six or eight months of life. As the child gets older, the eyes may stretch, with minimal or no corneal edema.

• Talk with the parent or caregiver. Obviously, the caregiver is a prime source of information, and you may need to enlist the caregiver’s help to manage the child if the child becomes fussy or uncooperative.

• As you move a little closer, distract the infant. Infants can be distracted by a number of things, but a bottle or pacifier is really helpful; if the child is feeding, he isn’t worried about you.

• Rely on handheld instruments. You can get a fair amount of information just from looking into the eye with a pen light, or, if you have one, a handhelp slit lamp. Other tools, such as visual fields, optical coherence tomography and other optic nerve analyzers aren’t useful until the child reaches school age, perhaps six years of age or older. If a child can’t sit still, you’re wasting your time attempting those tests.

• If the child is fussy, try leaving and returning after a few minutes. Sometimes just giving the child a little time will solve this problem. In the meanwhile, the mother or father may be able to calm the child down a little bit so you’ll get a better evaluation.

• Use the right tool to check intraocular pressure. Many clinicians worry about whether they’ll be able to check the pressure in an infant, but it’s not too hard to do. A hand-held tonometer is the way to go; you can’t use a slit-lamp-mounted tonometer with a small child. I recommend using the iCare rebound tonometer. It’s a tremendous asset when working with children because you don’t have to use an anesthetic eye drop. (When you do use an anesthetic eye drop in younger children and infants, they tend to cry. Ironically, infants get over it pretty quickly; toddlers, who are old enough to talk to you, get mad at you. Either way, you’re off on the wrong foot.)

• When measuring IOP, technique counts. Take your time and approach slowly. If possible, distract the infant with a bottle so she’s less concerned about you. If the child is a little older and more interested in her surroundings, a bright-colored toy may work, or the parent can talk to the child and hold her attention. The iCare will let you get a pretty rapid assessment of the pressure.

One important note: The child does have to be at least somewhat upright to use the iCare tonometer; it won’t work if it’s pointed down. (Even with this shortcoming, it’s a vast improvement over the previously available alternatives.) The Tono-pen or the handheld applanation tonometer are also very useful for assessing IOP, but an anesthetic drop is needed with either of these devices.

• For the back-of-the-eye exam, try to avoid restraining the child. In many cases you can get an assessment of the back part of the eye without holding the child down. Once you’ve gotten an idea of the pressure, instill some dilating drops and then leave the child alone for a while with the parents to quiet down.

Occasionally you may need to restrain an infant briefly to get an evaluation. But the more you can do without restraining the child, the better the information you’ll get. If the child is crying and screaming and squeezing, he’ll tend to produce a Bell’s phenomena: the eyes will go up and you won’t be able to see the back of the eye very well.

Pre-school-age Patients

A child who is out of the infant stage but is still too young to be in school is easy to manage in some respects, but tricky in others. In this situation, it helps to:

|

• Establish a rapport with the child. You can usually talk to a child in this age group. (It helps to get down on their level.) Go slowly, explain what’s going on, and do everything you can to calm their fears. You can coach them through the exam. They’re worried that you’re going to give them a shot or hurt them, so anything you can do to slow the process down and calm their fears will help. Given a little support, kids are amazingly adaptable.

• Get the parent to encourage the child. This can be a big help in terms of getting information and cooperation from the child.

• Have a technician or aide instill the dilating drops. That way the child doesn’t directly associate you with the experience. The transition will also give the child a few minutes to calm down.

• Don’t overreact to a large cup-to-disc ratio. The most common referral I’ve seen is a child with normal pressures but an enlarged cup-to-disc ratio. Based on the optic nerve exam these children are glaucoma suspects, but usually these kids don’t actually have glaucoma. There’s a huge spectrum of optic nerve configurations, especially in children, so what you’re seeing may just be a normal variation in physiology and anatomy. Additionally, some children who are severely premature have chronic central nervous system issues that can lead to a large cup and disc, so you need to check to see if there’s a history of prematurity.

If you do find a large cup-to-disc ratio, look for other signs of glaucoma. This will usually tell you that the child might not have glaucoma, so it’s something to watch rather than treat. Unless you’re sure it really is glaucoma, the child should be followed and monitored but not placed on drops.

School-age Kids

This age group is easier to work with because school-age kids can usually be examined like adults. They may need a little bit of time to understand what’s going on, but you can probably examine them at the slit lamp. If you prefer, you can use the iCare tonometer to get the pressure, but with children of this age you can also use applanation tonometry or the Tono-pen. If you need to instill an eye drop, it’s not so traumatic.

• Consider visual fields or imaging. Typically starting in the 6-to-8-year-old range, a visual field test can give you some idea about what’s going on with the child’s peripheral vision. However, like adults, kids have a visual field learning curve, and it can be more dramatic than an adult’s learning curve. So, the first test frequently isn’t very good.

For that reason, you should depend mostly on your clinical evaluation.

|

It’s also possible to do imaging studies of the optic nerve in school-age children using an OCT device, or the GDx or HRT. These may give you some useful information, as long as the child can sit still and maintain fixation.

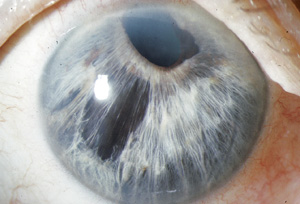

• Be on the lookout for subtle signs. Glaucoma that occurs in school-age kids generally involves high pressures, especially when the child has juvenile open-angle glaucoma. However, you should also look for other signs that support a glaucoma diagnosis, such as asymmetric cupping, variable pressures and subtle congenital ocular anomalies such as Axenfeld-Rieger. The latter are not always obvious on immediate examination, but can be spotted if you’re looking for them. In fact, you can do gonioscopy on children in this age group and sometimes find angle anomalies that are very mild variants, or note that the iris is subtly abnormal or that the pupil is a little eccentric. Children with those signs have about a 50-percent chance of developing glaucoma, and they tend to get it in childhood or early adulthood. Because of the subtle signs, children in this situation are easy to miss.

For example, I once saw a child who was thought to have an iris coloboma. (See photo, above.) The child actually was an Axenfeld-Rieger child who had glaucoma and ended up requiring surgical treatment. So it’s important to look carefully at the iris, especially when you know the pressure is elevated. Is there something going on that should arouse your suspicions?

Again, unlike the infantile age group, toddlers and school-age kids don’t usually have any signs or symptoms other than pressure and cupping. So it’s very important to check the pressure and look at the optic nerve carefully.

• Engage the child during the exam. As with the preschoolers, don’t be afraid to talk to the child. Explain what you’re doing. You can also do things like changing the light if the child is sitting at the slit lamp. Show the green light, then the blue light. Keep talking to the child and encourage him. These approaches will help you get much more useful information than if you rush or don’t involve the child.

Working With the Parent(s)

Enlisting the help of the parent or guardian is crucial, both when the child is in the office and when the child is at home. (Outside of the office, parents serve two very important purposes: They’re responsible for bringing the child to the appointment, and they’re responsible for administering eye drops.) To optimize their help:

• Get the parents or guardian on your side. During the exam itself, parents are integral regardless of the age of the child. They can help by providing historical information about the child’s medical history and development, and by helping with the child, both in terms of holding an infant and/or providing distractions while you examine the child. You also need to explain things to the parent, especially when the child is too young to communicate with you.

Given how important the parent is in all of this, getting them on your side is crucial. A family history of congenital eye issues can also be very useful, and a brief examination of the parent’s eye can also be helpful for inherited conditions.

• Educate parents about eye drop issues. Most parents find it challenging to make sure the child’s eye drop is used appropriately, so you’ll need to educate them about managing this. First and foremost, the parent needs to understand that the drops are very important. Young children don’t like eye drops, so the parent has to be very patient and tenacious to get through the process and make sure the drops are used. The main thing is for the parent to keep trying and working with the child. If the child is very young, it may take two people to get the drops in, because they’re going to have to hold the child down.

With older kids, that’s less of an issue. However, a different problem may arise: After a child has been taking drops for a while, the parent will sometimes leave it to the child to be responsible for using the drops at too early an age. The result, of course, is that the child isn’t adherent and the parents aren’t checking up on him. Parents need to be warned not to make this mistake.

• Be prepared to manage having extra kids in the room. This is usually very distracting, unless a brother or sister is old enough to be helpful. In most cases, having extra kids in the room makes things worse, because the parent’s attention is partly on the other child or children. If I have two parents, multiple children and one patient in the room, I’ll ask one parent to take the extra kids out to the waiting room so I can focus on the patient with the remaining parent. Of course, if there’s only one parent, you’re stuck. Sometimes I’ve had to ask support staff to come and distract the other kids temporarily to keep them out of the fray while I’m trying to evaluate the child who has the problem.

• Be prepared to manage the parents’ fears. Another concern with parents is their reaction to an initial diagnosis. Often, the parents are shocked that the child has a potentially serious problem. So part of our job is to counsel the parents as far as what treatment options are available, and impress on them that this does not mean the child is necessarily going to go blind. Of course, some diagnoses are more difficult in this respect than others. A child might have a very severe congenital anomaly with corneal opacity and a malformed eye and also have glaucoma; that’s a very tough diagnosis. But many forms of childhood glaucoma are treatable. Either way, we have to calm the parents’ fears about the child going blind and emphasize all the resources we have for addressing the problem.

As a doctor who accepts these kinds of referrals, I’ve had parents come in reporting alarming comments made by referring doctors, possibly because the referring doctor had encountered a child who didn’t do well in the long run. If you’re going to refer—and even if you’re not going to refer—I’d suggest avoiding talking about prognosis. Instead, emphasize the variety of treatment options. Some of these children do very well with treatment; some do okay; and even those who end up with pretty severe vision loss can still function. So the key thing is to avoid being too negative.

• Don’t let parents jump the gun. Parents frequently try to ask too many questions before you’ve even done the examination. You have to say, “Bear with me—I don’t know anything yet.”

• Don’t start the exam unless a parent or guardian is in the room. Remember, legally, you have to have the parent in the room until the patient is at least 18 and no longer a minor. If a school-age patient comes in but the parent goes off and does something else, don’t start examining the child until the parent or guardian is back in the room. If something happens while the parent is out of the room, medico-legally you won’t be in good shape.

Referring a Patient

Plenty of ophthalmologists choose to refer young patients, simply because they feel ill-equipped to help them. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with referring them, but you can help the eventual treatment of the patient by using a few simple strategies.

• If you refer, gather as much information as possible first. Deciding which cases are worthy of referral depends on your comfort level, but in any case it will help the next doctor if you can provide some basic information about the child’s condition. History details are helpful, and if you can’t get a pressure, at least provide a gestalt of the situation, which you should be able to put together from a distance. If the child is older, get a pressure. And if possible, let the next doctor know whether the child is able to do a visual field test.

• Know when to refer. When to refer depends on the circumstances. Generally, if you see a child that you think has new-onset glaucoma, you should refer right away. Primary congenital glaucoma is an automatic referral, because the treatment approach is usually surgical. (Response to angle surgery—i.e., goniotomy and trabeculotomy—can be very good.) Referring quickly makes sense because there’s no mystery in this situation; the treating surgeon will know what to do.

If the child is in the older age range and you’re suspicious that glaucoma is the problem, you should at least do a few basic tests before referring. On the other hand, if the pressure’s high and it looks very clear-cut, you should start medical therapy and refer the child to someone who can do surgical treatment if the child fails to respond to medication.

|

Most of the time a general ophthalmologist acts as a triage point for moving on to a pediatric ophthalmologist or someone with more experience treating glaucoma. If a general ophthalmologist does treat a child, it’s usually because there’s no pediatric ophthalmologist available. Pediatricians often serve as a referral point as well; they tend to refer to pediatric ophthalmologists, although in these cases they might choose to refer to someone with expertise in glaucoma.

• Know whom to refer to. Pediatric glaucoma tends to be handled by glaucoma specialists and pediatric ophthalmologists using a team approach. A pediatric ophthalmologist will be involved with continuing care, including amblyopia therapy and related treatments, especially if the child is very young. Some pediatric ophthalmologists are facile at dealing with the surgical aspect of the glaucoma as well as the medical management, and will handle all aspects of patient care including amblyopia treatment. [For a way to find specific names of doctors to refer to, see “Take advantage of new resources,” below.]

General Tips

Regardless of the child’s age, a few basic strategies will stand you in good stead:

• Allow plenty of time for the exam. Examining a child takes a few more minutes than an adult exam. It’s not something that can be done in a hurry, but you can often get the information you need.

• Don’t go too fast. Sit back, take a history, gather as much information as possible at a distance and try to figure out the onset of the symptoms.

• If necessary, plan to do the exam under anesthesia. If you can’t get the information you need, especially with an infant, then an exam under anesthesia is the way to go. However, that type of exam needs to be done in a pediatric hospital, or with a trained pediatric anesthesiologist present. You’ll also need to be prepared to deal with whatever you diagnose while the patient is on the table—possibly even doing surgery during the first exam.

• Remember that age alters symptom presentation. Again, infants tend to have signs and symptoms when glaucoma is present. With older kids, you have to sniff out the problem and look carefully at everything. They may not develop corneal enlargement or buphthalmos with increased intraocular pressure.

• Keep the light lower than usual. If you come at a child with a bright light, it’s painful. So always start by looking at the eye with the light from a distance. And when you come closer, if you’re using the indirect, don’t turn the light up to the brightest level. Likewise, if the child can sit at the slit lamp, keep the light low.

• Consider purchasing an iCare tonometer. As noted, this is a very helpful tool for getting pressures with children. It’s also helpful with elderly patients who are either wheelchair-dependent or have dementia, as well as patients who have the squeeze phenomenon when you try to check their pressure (i.e., you come at them with something and they reflexively close their eyes and squeeze and start blinking). As a glaucoma specialist I find the iCare tonometer useful on both ends of the age spectrum, and occasionally in the middle, if checking the pressure is difficult because of the squeeze phenomenon.

|

• Take advantage of new resources. I’m involved with a new organization called the Childhood Glaucoma Research Network. Because Internet resources designed to help doctors and parents managing children with glaucoma have been very limited, we’re building a website to serve that purpose. It’s meant to provide useful information for both parents and ophthalmologists who are trying to find a referral doctor for a pediatric glaucoma patient. (The doctors listed on our site are self-identified pediatric glaucoma specialists.) We also want the website to function as a forum for related issues, such as: How should we organize and classify these diseases? How should we study them? How can we pool our resources? (The rarity of childhood glaucoma makes it harder to study, so pooling our resources is important.) The doctors behind this organization have no financial incentive for participating; we just want to help kids who have glaucoma. You can visit the site at

gl-foundation.org/.

• Don’t panic. Perhaps this is the most important piece of advice for ophthalmologists who seldom encounter children with glaucoma. Just try to get as much information as you can, even if it’s only historical information from the parents and a gestalt of what’s going on with the child. And don’t be afraid to attempt a pressure reading.

Getting the Ball Rolling

Whether you choose to refer, follow the child or treat, there’s no question that these young patients need our help every bit as much as older patients—perhaps even more. Hopefully, these strategies will help you do the best possible job of helping them. REVIEW

Dr. Beck is the William and Clara Redmond Professor of Ophthalmology and director of the glaucoma section at Emory Eye Center at Emory University in Atlanta. He has no financial interest in any instruments mentioned, including the iCare tonometer.