Call it a case of mounting evidence eating away at popular wisdom. The use of YAG laser vitreolysis and vitrectomy to treat vitreous floaters has always seemed nearly off-limits to most right-thinking ophthalmologists. But more retinal specialists and some anterior segment surgeons are moving away from blanket views of pathologies, learning more about the nuances of these visual disturbances and intervening with improved techniques and technologies when treatment seems necessary.

In this report, they share their reasons and strategies—and precautions to take to ensure that you proceed with care.

Considering Vitrectomy

Retinal specialists say vitrectomy remains the conventional—if not widely used—treatment for vitreous floaters. Before deciding to operate, they continue to carefully consider risks for complications, such as cataract formation, glaucoma, endophthalmitis, retinal tears, retinal detachment, hypotony, choroidal effusion, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, vitreous hemorrhage, cystoid macular edema, optic neuropathy and phototoxicity.1,2,3 With these assessments in mind, Chicago retinal specialist Jennifer Lim, MD, says she always takes a hard look at the need for treatment when responding to the many patients who come to her with complaints of vitreous floaters, including high myopes and those with a history of vitreous detachments.

|

“The patients I treat with vitrectomy have chronic floaters that haven’t abated, usually for at least four months,” says Dr. Lim, Marion H. Schenk chair in ophthalmology, director of the retina service and vice-chair for diversity and inclusion at the University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine. “I first want to make sure they’re not accommodating to their symptoms. I also want to find out if the floaters are affecting their adult activities of daily living, such as causing difficulty reading or driving. For extremely troubled patients who report symptoms that haven’t necessarily been in concert with my exam findings, I’ve asked them to undergo psychological assessments to confirm that they’re not affected by anxiety disorders or some form of psychological condition.”

Dr. Lim points out that some patients with chronic vitreous floaters or large Weiss rings can’t perform their jobs, especially when sharp vision is needed. Multiple floaters in the mid to posterior vitreous can cause difficulty in reading, driving, computer usage and concentration, she notes.

“These are the patients I will operate on,” she notes. “As a retinal specialist, I’ve done a lot of vitrectomies. Admittedly, though, I haven’t done a lot of “floaterectomies.” But I’m now more amenable to doing them than I was three years ago. When indicated, the procedure is extremely gratifying and helpful to the patient. In fact, I just did one of these procedures yesterday.”

|

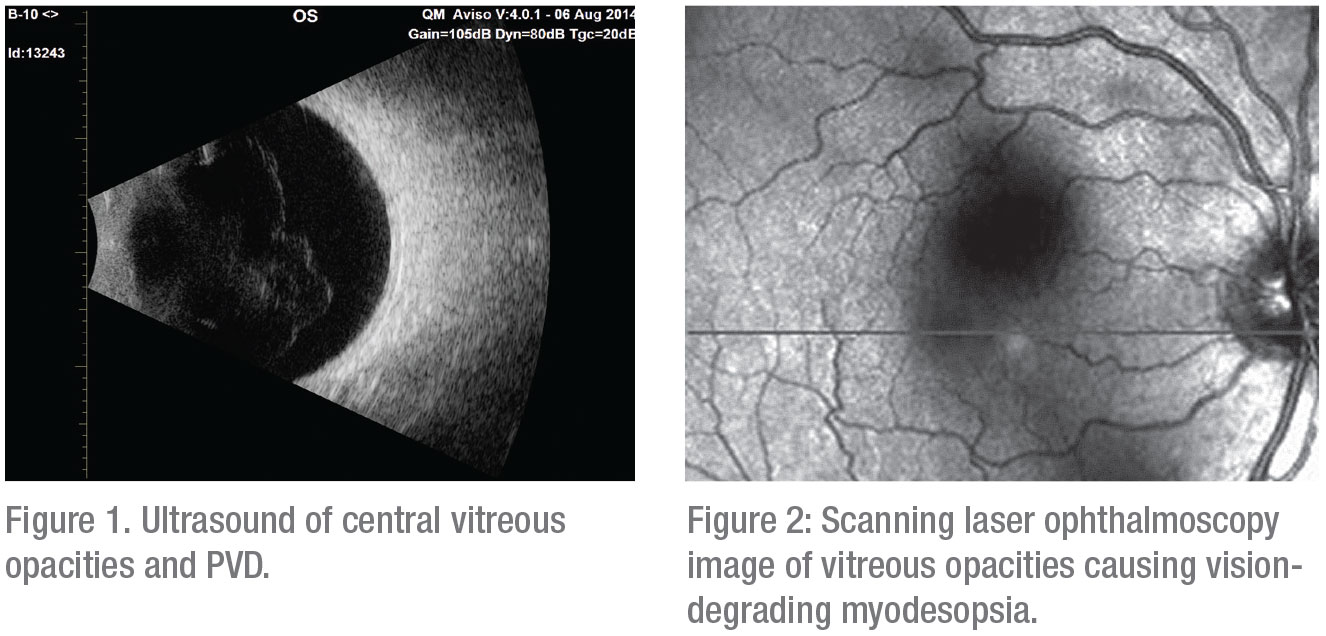

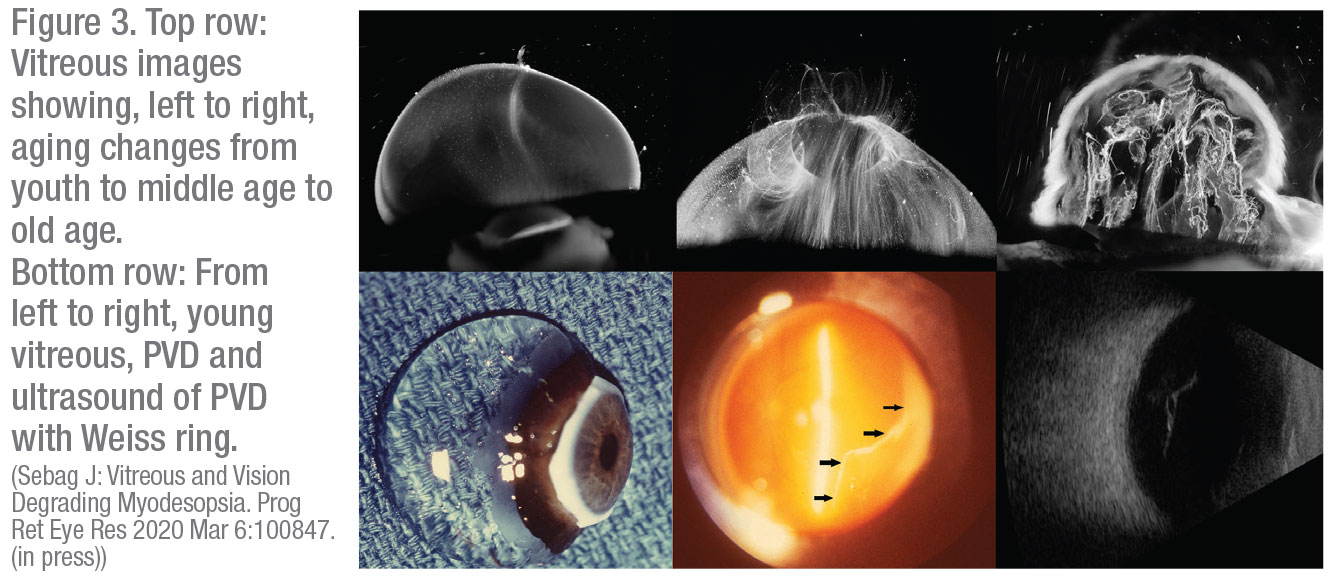

To qualify a patient for this surgery, Dr. Lim has learned to use objective data, borrowing from some of the techniques developed by Jerry Sebag, MD, FACS, senior research scientist, Doheny Eye Institute/UCLA and professor of clinical ophthalmology, at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. Dr. Sebag, also founding director of the VMR Institute for Vitreous Macula Retina in Huntington Beach, California, has advanced the use of pars plana vitrectomy to treat visually-significant vitreous opacities that create what he calls the “visual phenomenon of floaters”—but only in clinically significant cases, which he describes as vision-degrading myodesopsia.4

He says he uses the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire, followed by a vitreous floaters functional questionnaire he has developed that’s “more specifically related to the impact of floaters on patients’ well-being and quality of life.”5 Dr. Sebag explains that he also measures contrast sensitivity function to identify patients who might benefit from a vitrectomy. He and other researchers have discovered that opacities in the vitreous body following PVD in older patients and in association with myopic vitreopathy in younger patients degrade the contrast sensitivity function by an average of 91 percent.6,7,8,9

Dr. Sebag says he also relies on the “overlooked” value of ultrasonography, which he says can identify structures in the vitreous that help explain degradation of the contrast sensitivity function and the patient’s level of unhappiness and poor quality-of- life.10,11,12

“When findings are abnormal, I’m comfortable clearing patients for symptom-remedying surgery and recommending vitrectomy,” states Dr. Sebag.

The “flip side” of using these measures is that this approach can be used to confidently rule out treatment for patients, he notes. “Lots of people have floaters, but fewer have vision-degrading myodesopsia,” he says. “I can legitimately tell a patient, ‘Your case is not sufficiently severe for therapy because your contrast sensitivity function is not as bad as what we usually see in patients who do need therapy.” (Dr. Sebag explains his approach in “Straight from the Cutter’s Mouth: A Retina Podcast,” Dec. 12, 2017, linked here by permission of the publisher. retinapodcast.com/episodes/2017/12/12/episode-78-vision-degrading-vitreopathy-with-dr-jerry-sebag)

Documenting Floaters

Like Dr. Sebag, Dr. Lim uses contrast sensitivity testing to determine if a patient may be a candidate for a vitrectomy. “It’s helpful that we can actually document the effects of vitreous floaters in these ways,” she says. “I seriously consider treating patients who are significantly bothered by cloudy floaters, especially when their posterior hyaloid face is thickened or partly opacified, causing them to experience a film over their vision that won’t go away.”

So far, she says she’s avoided complications in patients she’s treated. “During the past five years, in the fewer than 10 floaterectomies that I’ve performed, no patient has developed cataracts,” she says. “Keep in mind these patients tended to be on the younger side. And if they’re older, many have already had their cataracts removed.” Every case is an exercise in caution, she notes, especially for high myopes, who are at increased risk of retinal tears and detachments.

“When you’re trying to induce a PVD intraoperatively, you risk inducing tears at the vitreous base, along with a retinal detachment,” she says. “But fortunately I haven’t had any cases of postop endophthalmitis, or any tears or retinal detachments interoperatively.”

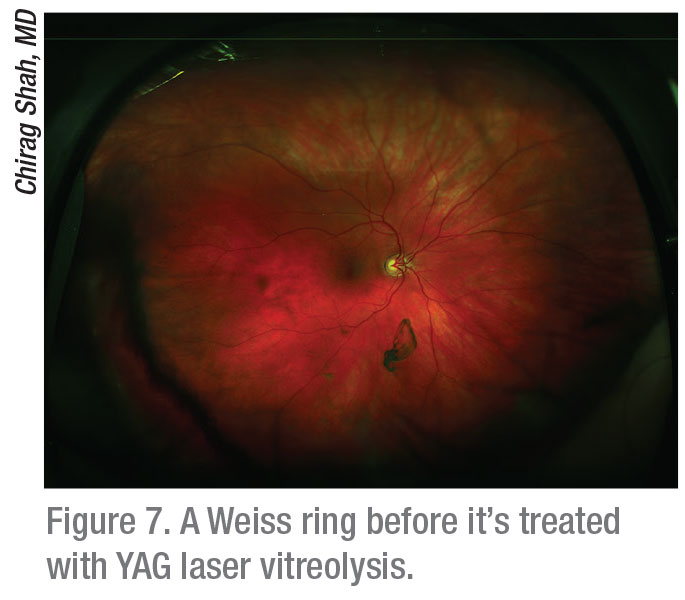

Dr. Lim believes that YAG laser vitreolysis, the only alternative to vitrectomy and observation, may be worth exploring because of the recent promise it’s shown.13,14 “If we had a YAG laser in our office, I might consider trying it on an ideal patient, such as one who has had cataract extraction and who has a Weiss ring,” she says. “I wouldn’t use the laser for small floaters. I’m still dubious about the laser to some extent, though, because it creates lots of tiny floaters.”

Clarifying Floaters

One of the challenges of floaters is understanding their diverse levels of significance, according to Chirag Shah, MD, MPH, a partner at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston. “Floaters can appear as rings, wisps, sheets, squiggles or other patterns in the central or peripheral vision, varying widely in terms of how they affect patients and how clinicians respond to them,” he says.

When evaluating vitreous floaters, Dr. Shah rules out retinal tears, hemorrhage, inflammation and other pathologies that could be at the root of the problem. He also makes sure the floaters match the symptoms his patient reports. “A discrepancy between what I see and what the patient expresses might indicate that the patient is overreacting to his floaters and, thus, might not be a good candidate for treatment,” he says.

If a patient reports significant floaters that correlate with symptoms—and the patient is sufficiently bothered by the floaters—Dr. Shah follows the patient closely. “I tell the patient that, over time, the brain can often adapt and ignore those floaters. This approach is, by far, the safest option for floaters.”

He notes that most of his patients neuroadapt and cope with the floaters, prompting him to monitor them in the long term. “I try to reassure these patients,” he adds. “It’s very uncommon that I recommend further treatment for floaters, such as a YAG laser treatment or vitrectomy.”

Beyond Reassurance

Dr. Shah takes a different course when he determines that patients are coping with very bothersome symptoms. “Again, the appearance of their floaters has to match their symptoms,” he says. “We discuss the options of observation, YAG laser vitreolysis and vitrectomy. If they have discrete floaters that continue to disrupt their lives, such as a Weiss ring, I’ll refer them for YAG vitreolysis.”

Sheets of floaters, diffuse floaters and excessive numbers of tiny floaters also pose a challenge that may require a vitrectomy. Dr. Shah turns to vitrectomy only two or three times a year for vitreous floaters. “I emphasize the downsides to the patient, such as a guaranteed risk of cataract formation and a small but real risk of a retinal tear and retinal detachment, as well as risks of infection, bleeding and anesthesia,” he says. “I send them home with literature and tell them to do their homework so that they know what they are getting into. If you can avoid doing a vitrectomy and satisfy a patient with YAG vitreolysis, that is by far the safer way to go.”

Dr. Shah recently joined one of his partners, Jeffrey Heier, MD, to oversee a six-month randomized controlled trial of 52 patients who either underwent YAG laser vitreolysis or weren’t treated.14 “There was no risk of infection, and only a very low risk of elevated intraocular pressure in patients treated with YAG vitreolysis,” he says. “There was also a low risk of worsening floaters by fragmenting them into smaller pieces with the laser, instead of vaporizing them. It’s important to emphasize that the risks were less than the risks of vitrectomy.”

The risks of YAG vitreolysis include glaucoma, retinal tear, retinal detachment, cataract from striking the lens with the laser and retinal damage from striking the retina, says Dr. Shah. To minimize risks of lens or retinal damage, he recommends ensuring a safe distance between the focal point of the laser and the retina and crystalline lens. In his study, he required the Weiss ring floater to be 5 mm posterior to the posterior capsule of the crystalline lens and 3 mm anterior of the retina, as measured by B-scan.

Bullish on Vitreolysis

I. Paul Singh, MD, a glaucoma and anterior segment specialist in Racine, Wisconsin, has offered laser vitreolysis to dozens of unhappy patients. He accepts referrals from Dr. Shah in

Boston, as well as from referring physicians all over the world.

“If a patient isn’t a good candidate for a vitrectomy, then vitreolysis can be a good option,” says Dr. Singh, president of the Eye Centers of Racine and Kenosha. He performs about 10 YAG laser vitreolysis procedures per week, in addition to his 25 cataract surgeries and regular visits with glaucoma patients. “In the case of a Weiss ring, for example, laser floater treatment can be fantastic,” he continues, noting that this treatment typically involves an average of only 1.2 sessions. “We’ve found more than 90 percent of patients who undergo this treatment are very happy. Surgeons can easily identify good candidates and correlate signs and symptoms. If, for example, a patient has a solitary lesion, an opacity, such as Weiss ring, or a mass, the laser can help, especially for patients who are phakic or pseudophakic and who don’t want to undergo a vitrectomy.”

Dr. Singh says YAG laser vitreolysis poses “very low relative risks,” noting that, in one series of 1,264 cases, he recorded an adverse event rate of 0.8 percent, which included seven IOP spikes, two phakic lenses that were struck by the laser and one retinal hemorrhage.

“Four patients had a history of uveitis that didn’t worsen and 27 had diabetic retinopathy and didn’t develop macular edema,” he notes. “Four patients developed vitreomacular traction that resolved immediately.”

Enough Evidence?

|

Despite these positive results, many leading retinal specialists say claims that YAG laser treatments can resolve floaters remain to be substantiated and that, currently, only vitrectomy has any proven value.15,16 Dr. Sing says he’s well-acquainted with this perception. “The problem is that, until recently, we didn’t have great technology to more efficiently and safely take care of significant vitreous floaters,” he notes. “The conventional YAG lasers that we used in the past were designed for posterior capsulotomy and iridotomy treatments. They provided a limited view of the posterior vitreous, making it difficult to identify floaters and membranes to target. The risk of damage to surrounding ocular tissue is also greater if you’re not able to visualize the posterior vitreous.”

He notes that conventional YAG lasers have had non-coaxial illumination towers, which provided illumination from a source that was different than the optical system. “The light was oblique and, as a result, we couldn’t see behind the capsule very well. Identifying many of the clinically significant and symptomatic floaters wasn’t possible.”

Another limiting factor of conventional lasers was that energy delivery wasn’t optimized, he adds. “The laser used now has a truncated energy beam,” he points out. “So, less energy is needed to create optical breakdown. In general, the previous studies done on YAG vitreolysis were done with energy settings that were entirely too low,” he continues. “We’re talking about 1 mJ or 2 mJ. You can actually go up to 4 mJ, 5 mJ, 6 mJ or even 7 mJ, depending on where a floater is located. Also, the previous laser treatments were done with 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 or 100 shots. Often, you actually need to use 400 or 500 shots, depending on the floater itself. So people who have some skepticism about the YAG laser for treatment of vitreous floaters seem to be clinging to concerns from many years ago. Recently, we’ve presented a lot of compelling data on safety and efficacy at the AAO and ASCRS meetings.”

Cutting-edge Vitrectomy

Dr. Sebag, the West Coast clinician and researcher who introduced contrast sensitivity function testing and ultrasonography to the preop assessment of potential vitrectomy patients, doesn’t refer his patients for YAG laser vireolysis treatment. But he does use vitrecomy more aggressively than most. When deciding to operate, he says he takes careful steps to minimize risk and complications. The surgery is performed at an ambulatory surgery center under retrobulbar anesthesia. The concept of “less is more” is the guiding principle of the intervention.

|

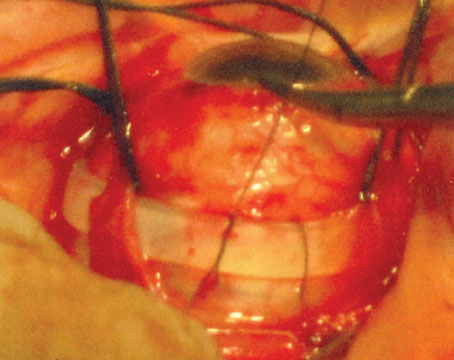

“I use a 25-ga. instrument, since I don’t see any advantage to 27-ga. instruments in this setting,” he says. “The procedure is sutureless. Two aspects of the vitrectomy are especially important. First, I don’t induce a surgical PVD in an individual who doesn’t already have one, in order to prevent an increased risk of iatrogenic retinal tears, but also to avoid increasing intravitreal pO2 levels too much. Studies show that following PVD, pO2 levels rise, and that’s what contributes to lens opacification and cataract formation.11

Second, I leave 3 or 4 mm of gel vitreous intact behind the lens. This is because vitreous contains antioxidants that mitigate the effects of reactive oxygen species that induce the cross-linking and protein aggregation in the crystalline lens that lead to cataract formation.”11

Studies have shown that the incidence of post-vitrectomy cataract surgery is markedly lower following a limited vitrectomy as opposed to extensive vitrectomy with PVD induction—as low as 16.9 percent with an average follow-up of 32 months, Dr. Sebag notes.6,12

“To minimize risks, I’ve employed a limited vitrectomy,” continues Dr. Sebag. “Some would call it a core vitrectomy. Basically, I remove the central vitreous that contains the opacities. In some individuals, the posterior vitreous contains opacities. And I do go down close to the fundus, which is also very important to characterize preoperatively with ultrasound and OCT, showing me what’s going on in the preretinal posterior vitreous that may require attention.

I have about three or four dozen patients in their 20 and 30s, myopes who have myopic vitreopathy in the posterior vitreous, which is the cause for their vision-degrading myodesopsia. They’ve all done very well without forming cataracts now, six to seven years after their procedures.”

Minimizing Iatrogenic Breaks

|

When evaluating the data from some 200 of these cases, Dr. Sebag says about 22 percent underwent laser or cryoretinopexy three months preoperatively. “When I recognize lattice with erosions or holes or other lesions that I think would put the patient at too much risk for a vitrectomy, we’ll offer them preop prophylactic treatments,” he notes. “I think that has resulted in our low, 1.5-percent incidence of postop retinal tears and detachments.”

That said, Dr. Sebag offers this precaution: “Prophylactic laser isn’t necessary on every patient. Just a careful peripheral fundus exam with scleral depression is enough to identify cases that need prophylaxis.

“I don’t use the YAG laser to treat vitreous opacities, as there are no studies to date that prove efficacy,” he adds, “although the most recent study suggests that a prospective randomized trial using objective quantitative outcome measures is warranted.”9,17,18

New Possibilities

Ophthalmologists expect to keep pushing the envelope on vitreous floaters. Concern over quality of life and the increasing reach of therapeutic approaches will drive change.

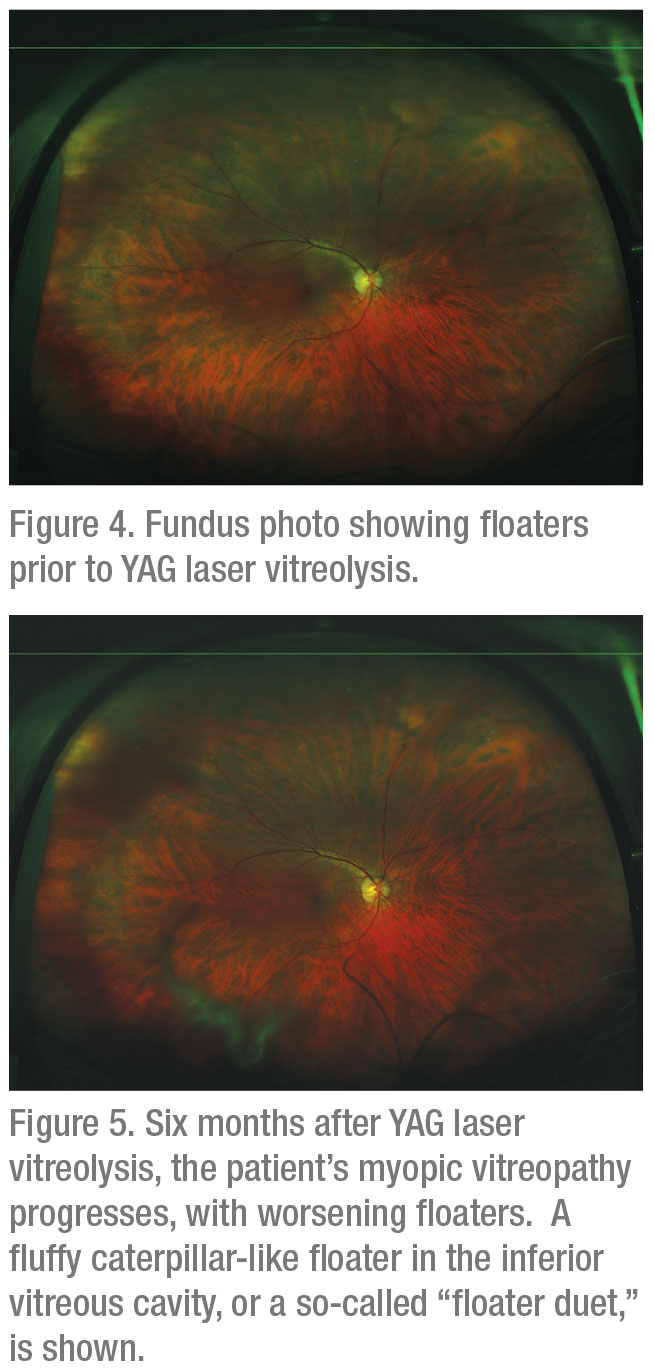

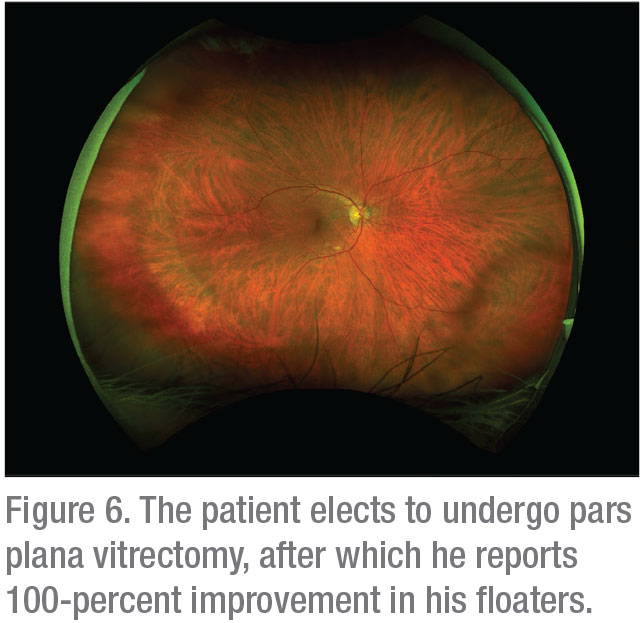

“One recent experience I had with a patient demonstrates at least one example of new ways to respond to floaters,” says Dr. Shah in Boston. (See Figures 3, 4 and 5 on page 60.) “The patient had floaters that I tried to treat with YAG laser vitreolysis in our clinical trial. His myopic vitreopathy progressed, and he developed worse floaters.”

Next, Dr. Shah says he offered to perform a vitrectomy on the patient, which helped clear his floaters and left him completely satisfied. “I don’t think we lose much, if anything, by trying this type of step-wise approach, from observation to YAG vitreolysis to vitrectomy,” he concludes. “Managing floaters is different than it used to be.” REVIEW

Dr. Lim is involved in grants/research for Genentech, Regeneron, Graybug, Stealth, Chengdu Kanghong and Alderya. She’s a consultant for Novartis, Ophthea, Aura Biosciences and Santen, and she receives honoraria for meetings from Alcon and Allergan. Dr. Sebag is a former consultant to ThromboGenics, Johnson & Johnson and Roche. Dr. Shah provides speaking and research services to Ellex. Dr. Singh is a consultant for Ellex, Allergan, Alcon, B+L, Aerie, Ivantis, Sun, Shire, New World Medical, Sensimed and Zeiss.

1. Stein JD, Zacks DN, Grossman D, et al. Adverse events after pars plana vitrectomy among medicare beneficiaries. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:12:1656-63.

2. Day S, Grossman DS, Mruthyunjaya P, et al. One-year outcomes after retinal detachment surgery among medicare beneficiaries. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;150:3:338-45.

3. Chang S. LXII Edward Jackson lecture: Open angle glaucoma after vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:6:1033-1043.

4. Sebag J. Vitreous and Vision Degrading Myodesopsia. Progr Ret Eye Res 2020; March [Epub ahead of print]

5. Sebag J. Floaters and the quality of life. (Guest Editorial) Am J Ophthalmol 2011; 152:3-4.

6. Sebag J, Yee KMP, Nguyen JH, Nguyen-Cuu J: Long-term safety and efficacy of vitrectomy for vision degrading myodesopsia from vitreous floaters. Ophthalmology Retina 2018;2:881-7.

7. Garcia G, Khoshnevis M, Yee KM, Nguyen-Cuu J, Nguyen JH, Sebag J. Degradation of contrast sensitivity following posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol 2016; 172:7-12.

8. Garcia G, Khoshnevis M, Nguyen-Cuu J, Yee KMP, Nguyen JH, Sadun AA, Sebag J. The effects of aging vitreous on contrast sensitivity function. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018; 256:919-25.

9. Milston R, Madigan M, Sebag J. Vitreous floaters: Etiology, diagnostics, and management. Surv Ophthalmol 2016;61:2:211-27.

10. Mamou J, Wa C, Yee K, Silverman R, Ketterling J, Sadun A, Sebag J. Ultrasound-based quantification of vitreous floaters correlates with contrast sensitivity and quality of life. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:1611–7.

11. Ankamah E, Sebag J, Ng E, Nolan JM. Vitreous antioxidants, degeneration, and vitreo-retinopathy: Exploring the links. Antioxidants 2019;9:1.

12. Yee KM, Tan HS, Lesnick-Oberstein SY, Filas B, Nguyen, J, Nguyen-Cuu J, Sebag J. Incidence of cataract surgery after vitrectomy for vitreous opacities. Ophthalmology Retina 2017;1:154-7.

13. Lim JI. YAG laser vitreolysis-Is it as clear as It seems? Comment on YAG Laser vitreolysis vs sham YAG vitreolysis for symptomatic vitreous floaters: A randomized clinical trial. [JAMA Ophthalmol 2017] JAMA Ophthalmol 20171;135:9:924-925

14. Shah CP, Heier JS. Long-term follow-up of efficacy and safety of YAG vitreolysis for symptomatic Weiss ring floaters. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2020 1;51:2:85-88.

15. Kokavec J, Wu Z, Sherwin JC, et al. Nd:YAG laser vitreolysis versus pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous floaters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017:1;6.

16. Milston R, Madigan MC, Sebag J. Vitreous floaters: Etiology, diagnostics, and management. Surv Ophthalmol;61:2:211-27.

17. Sebag J. Methodological and efficacy issues in a randomized clinical trial investigating vitreous floater treatment. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:4:448.

18. Nguyen JH, Nguyen-Cuu J, Yu F, Yee KM, Mamou J, Silverman RH, Ketterling J, Sebag J. Assessment of vitreous structure and visual function after Nd:YAG laser vitreolysis. Ophthalmology 2019;126:11:1517-26.