Treating dry eye—once widely considered a “nuisance diagnosis”—has now become the focus of countless clinical studies, products and articles. And as interest in managing dry eye has increased, the need to understand the details of a given patient’s problem and refine your treatment to appropriately address those details has also grown.

Here, surgeons well-versed in the details of dry-eye treatment share their experience and advice regarding managing the different dry-eye diseases and severity levels that you’re likely to encounter in your patients.

The Problem with “Severity”

“Discussing severity in the field of dry eye is confusing,” notes Esen K. Akpek, MD, the Bendann Family Professor of Ophthalmology and Rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and director of the Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic at the Wilmer Eye Institute. “The reason for this is that what might be severe for the patient doesn’t necessarily look severe to the physician—and what looks severe to the physician might be trivial for the patient. The confusion is compounded by the fact that the field is relatively new and evolving. There are no agreed-upon, tried-and-true core outcome measures, like the ones you would use when designing a clinical study. We don’t know which specific sign or symptom matters in the long run.

“That’s not the case in many other areas of ophthalmology,” she continues. “For example, in glaucoma, the core outcome measures are changes in optic nerve cup-to-disc ratio and the visual field. In the field of dry eye, some of the measures that have been used matter to physicians; some matter to patients; and some matter to entities that approve drugs, such as the FDA. The problem is that none of them matter to all of these groups at the same time, and none is known to have a bearing on the long-term outcomes of dry eye.”

Dr. Akpek notes that it used to be widely believed that signs and symptoms of dry eye are discordant. “Based on new research, that may not be true,” she says. “We just published a paper in the journal Ophthalmology showing that the symptoms reported by the patient totally correlate with the signs—if you measure them after the patient has been reading for 30 minutes, which stresses the eyes’ surface.1 We found this to be true even in normals, but the worsening was especially noticeable in dry-eye patients, probably because they don’t have enough tear-film reserve. At that point the dry-eye signs did correlate with the initial baseline symptoms.

“This is similar to angina,” she continues. “If you have angina, you get pain upon exertion because of not-sohealthy coronary vessels. If you evaluate the patient at rest, you can’t see the problem or measure it, even with an EKG. Similarly, if you measure eyes when they haven’t been stressed, the signs of dry eye might not be obvious, especially in mild to moderate disease.

“After doing this study we concluded that what dry-eye patients complain about is absolutely real,” she says. “The problem is, when we take a one-time severity measurement in the clinic, it may or may not correlate with what the patient says, depending on whether or not the eyes were recently stressed. For this reason I think we should always base our treatment on what the patient says, even if we don’t see the signs. By the time we see the signs of ocular surface disease and staining at the slit lamp, the disease is usually pretty advanced. And if the Schirmer score is bad, that’s even worse—that patient has chronic, severe dry eye.

“I used to care mostly about the signs,” she concludes. “Now I listen to the patient.”

Determine the Cause First

If there’s one key lesson that’s emerging from the growing interest in dry eye, it’s that dry eye signs and symptoms can be caused by a number of different problems that previously might have remained undiagnosed. To address the signs and symptoms of dry eye, regardless of their severity, you first need to identify the nature of the exact problem the patient is dealing with.

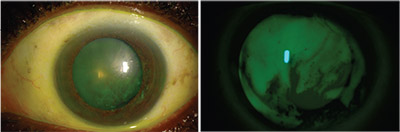

|

| Left: Slit-lamp picture of a patient being evaluated for cataract surgery demonstrating poor tear film overlying the cornea. Right: The same cornea under a cobalt blue light, showing a thin and irregular tear film. Photo by Esen K. Akpek, MD |

“You wouldn’t necessarily treat a Sjögren’s patient with aqueous deficiency the same way you’d treat a rosacea patient with bad blepharitis and evaporative dry eye, or the way you’d treat someone with goblet cell deficiency caused by Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or the way you’d treat someone with Parkinson’s who has an incomplete blink,” says Kenneth A. Beckman, MD, FACS, director of corneal services at Comprehensive EyeCare of Central Ohio, and a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Ohio State University. (Dr. Beckman was part of the team that developed the CEDARS dry-eye treatment protocol.) “They all have different underlying mechanisms.

“That’s why it’s important to first find the underlying pathway, keeping in mind that the patient may have multiple conditions,” he says. “For example, a patient could have both blepharitis and aqueous deficiency, and you’d need to treat both. After you’ve determined the etiology, then treat according to the severity level. Don’t just use a shotgun approach and say, ‘This person is severe, so he should get this treatment.’ Maybe the patient just needs lid-tightening.”

Treating Aqueous Deficiency

Dr. Beckman says that when treating aqueous deficiency he’d start with lubricants. “Lubricants are generally the first step regardless of the underlying cause,” he notes. “Then I’d move to anti-inflammatories, such as a steroid or cyclosporine or lifitegrast. If the patient still isn’t getting relief, there are more esoteric options that are not necessarily commercially available that you can get compounded, like serum tears or amniotic membrane extract. You can also try punctal plugs. We have lots of options when treating aqueous deficiency.” Another option is the recently approved Cequa (cyclosporine ophthalmic solution) 0.09%, from Sun Pharma. Sun says the drug provides the highest approved concentration of cyclosporine A, and can overcome solubility issues by way of nanomicellar technology.

Bruce Koffler, MD, medical director of Koffler Vision Group in Lexington, Kentucky, says he typically bases his treatment choices on the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop II report (DEWS II). “The report gave us a nice schematic of severity levels and how we normally treat them,” he notes. “If a patient has early disease and falls into category one, I’m a big artificial tear user. I’ll try a variety of different tears, whether it be hypo-osmotic or hyperosmotic tears, or tears with different viscosities. Right now we’re using preservative-free artificial tears that have new lipid or mineral oil components. Some of the new ‘balanced’ tear products are also putting omega-3 supplements into the tears.”

| Severe Patient: Start Simple? |

| One key question regarding treating different severity levels is whether to start with simple, basic treatments or immediately move to more serious ones when faced with a severe patient who hasn’t already been treated. Kenneth A. Beckman, MD, FACS, director of corneal services at Comprehensive EyeCare of Central Ohio, says he prefers to start with the basic treatments and add more options as needed. “I like to proceed stepwise, rather than give the patient a lot of things at once,” he says. “I always start with lubricants and perhaps one intervention. Then I’ll bring the patient back in six weeks or so to see how he’s doing. If he’s improving, I may stay the course. If he hasn’t improved enough, I may add another option at that point.” Esen K. Akpek, MD, director of the Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic at the Wilmer Eye Institute, says that when faced with a patient who has severe dry eye, she doesn’t start with the most basic treatments. “I’m used to seeing people with very severe dry eye, such as Sjögren’s or graft-versus-host disease,” she explains. “These patients quickly lose vision from corneal complications, so I don’t have much patience. I treat dry eye as an inflammatory disease, just like uveitis. If it’s bad enough that I already see the signs, I hit it with everything I have. I put the inflammation down and work to improve the surface. Then I withdraw bit by bit as the patient improves. “On the other hand,” she continues, “if the patient is young and has mild dry eye—meaning the patient is mildly symptomatic— and there’s no underlying systemic inflammatory disease, then I might start with the basics. We can try warm compresses, work to improve the meibum, use artificial tears, limit digital screen time and so forth. But if I see ocular surface signs, then the problem is already severe, and I start the patient on a lot of different things all at the same time.” |

Dr. Koffler says if symptoms are mild, he’s inclined to start with artificial tears in a regular bottle, rather than preservative-free drops in a tuberette. “Those patients are not going to use the drops that often, and there are a number of good artificial tears in bottles that are easy to obtain and easy to use,” he notes. “Once the patient starts to get more symptoms and is using the tears more often, I might move to thicker artificial tears. I might also look for certain components that would help that patient. For example, I might look for artificial tears that have gelling components in them, so they’ll provide a longer-lasting effect. And I might start thinking about switching the patient to preservativefree drops in tuberettes, because if the patient is taking them more often, the preservatives might begin to cause ocular surface disease problems.” Dr. Koffler says if the dry-eye problem isn’t resolved he’ll move on to the next treatment category and begin to introduce other treatments.

When patients need more advanced treatment, Dr. Koffler says he often turns to autologous serum tears. “Autologous tears are extremely comfortable for the patient, and they contain multiple active growth factors for healing the epithelial surface,” he says. “Because they’re kept refrigerated, the coolness is also quite comforting.”

Dr. Koffler points out that it’s recently become much easier to obtain autologous serum tears. “Our local eye bank, and several other eye banks as well, have been happy to do the autologous tear work for a very reasonable charge,” he says. “They have a laminar-flow hood in their facilities, and they can do this under sterile conditions. The blood draw is taken care of as an outpatient, and the charge is typically based on the cost of the goods and the eye bank’s overhead. As a result, almost all of my patients can afford this. However, if they can’t, our eye bank has obtained a funding grant from the local Lion’s Club ensuring that everyone who needs autologous serum tears has access to them.”

Another option is amniotic membrane, which Dr. Koffler notes has recently become more readily available, with competition also causing the price to come down. “Today we can get nice round pieces of amniotic membrane to put right on the cornea and cover with a contact lens,” he says. “I sometimes use this for really severe dry eye, when the cornea has filaments and surface breakdown. It can help to get the healing started. It’s not for long-term therapy, because the membrane may only last three to five days, but it can be repeated.”

Dr. Beckman adds that some of his patients have tried the recently approved TrueTear Intranasal Tear Neurostimulator (Allergan). “This is an instrument that’s inserted into the nostrils to stimulate the nerves, leading to tear production,” he explains. “According to the company, it’s been shown to increase aqueous, lipid and mucin production, so it is not just reflex tears. This can bypass the traditional neuro loop and therefore may help in patients with neurotrophic corneas, and it’s also useful for patients who cannot or do not want to use drops. My patients have definitely seen an increase in tear production.”

Treating the Meibomian Glands

Dr. Akpek says that meibomian gland disease is very underdiagnosed in the field of ocular surface disease. “It reminds me of the old days when we didn’t know much about dental plaques, how we get dental cavities, and the importance of flossing and brushing,” she says. “By a certain age, everybody wore dentures; that was normal back then. Meibomian glands are the same. Dust and dirt get in there and you start making poorquality oil because of changes in hormones and other factors related to aging, menopause, and so forth. Then the glands get clogged up, and over a period of time they get damaged by distention, inflammation, fibrosis and tissue remodeling. They may even die off, and if they do they won’t regenerate. This is very common, but it’s always been under-recognized. Now I’m beginning to hear researchers say that meibomian gland dysfunction is the most common underlying etiology of dry eye and ocular surface disease.”

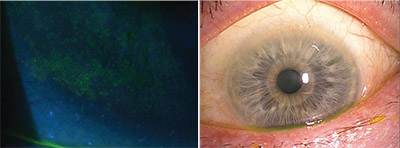

|

| Left: A slit lamp photograph of dry-eye-related superficial punctate keratopathy, as demonstrated with a Wratten filter. Right: An example of meibomian gland disease with telangiectasia, keratin plugs and a frothy tear film. Photo by Bruce Koffler, MD |

Dr. Akpek says her experience has convinced her that meibomian gland dysfunction is the main reason dry eye is more common in older individuals. “True aqueous deficiency is actually rare, and I think it’s almost always associated with an underlying autoimmune disease, something that causes lacrimal gland inflammation,” she says. “On the other hand, meibomian gland disease is age-related and very common. Over the long term it also leads to aqueous tear deficiency because of the ocular surface inflammation that’s caused by meibum deficiency.”

“If the problem is meibomian gland dysfunction, or lid margin disease, we’re going to emphasize warm compresses and lid hygiene,” Dr. Beckman says. “We may use antibiotic drops or ointments, omega-3 supplements— which actually could be helpful with any type of dry eye—and cyclosporine or lifitegrast drops. Sometimes we treat these patients with oral antibiotics like doxycycline, and sometimes we get compounded antibiotic drops or ointments such as metronidazole or clindamycin. Some of these treatments are very effective.”

In addition, more and more surgeons are using in-office or homebased devices that help to clear blocked meibomian glands. For an indepth discussion of currently available devices in this category, see “Devices for Treating Meibomian Gland Dysfunction” on page 36.

Treating Other Related Causes

Surgeons offer these suggestions when the problem isn’t simple aqueous deficiency or meibomian gland dysfunction:

• Goblet cell disease. “If the problem is goblet cell disease, we’ll address it with lubricants,” says Dr. Beckman. “Cyclosporine and lifitegrast also work really well for this, and these patients may also benefit from compounded vitamin A ointment.”

• Autoimmune inflammatory disease. “If I believe the patient has an autoimmune inflammatory disease such as Sjögren’s or lupus, then I’ll start to introduce T-cell inhibitor products that will be anti-inflammatory,” says Dr. Koffler. “We may even introduce some mild steroids, either for daily use or as a nighttime ointment, to quiet the inflammation.”

| The Patient Communication Factor |

| As with any treatment, aligning the patient’s expectations with reality is important. • Make sure the patient understands that dry eye is a chronic condition. “You don’t want a gap between what the patient expects and what you’re able to deliver,” says Young Choi, MD, medical director at InVision Ophthalmology in Homewood, Alabama. “Patients are often looking for a magic bullet. They as- sume that if they have the right medication, all of their symptoms will go away and they won’t ever have dry-eye problems again. That’s a setup for trouble because the patient may never be satis- fied, no matter how good the care you’re providing is. “I think doctors don’t always appreciate how important it is to communicate to the patient that dry eye is chronic,” he continues. “Patients need to understand that we can do a lot to lessen the symptoms, but the problem is never going to completely go away.” • Don’t tell the patient that he has dry-eye disease if the problem is meibomian gland disease, a blink problem or another issue. “Don’t jump to the diagnosis of dry eye,” says Bruce Koffler, MD, medical director of Koffler Vision Group in Lexington, Kentucky. “One of the things I’ve learned over the years is that we overuse this diagnosis. We do this at times because we get frustrated. A patient with grittiness, burning and redness is like a patient seeing an orthopedic surgeon for low back pain; there are so many things that can cause these symptoms that when we don’t have a quick, simple answer we just label it ‘dry eye.’ “If we do that, I think we’re doing the patient a disservice,” he continues. “A diagnosis of dry eye implies aqueous deficiency with classic staining or increased debris in the tear film. In fact, the patient may have rosacea, or a staph infection, or nighttime exposure because of a blinking problem. If the patient is told he has dry eye, he’ll Google that and get all kinds of misinformation about what’s happening to him and what needs to be done. “Of course, some patients may have multiple issues, including true dry eye,” he adds. “But if the patient has meibomian gland disease, let’s call it that. If the patient has a blink disorder, let’s call it that. Make sure we diagnose the problem correctly, and then let’s not lump all of these issues under ‘dry-eye disease.’ ” |

Dr. Akpek say she reserves the TrueTear device for patients with severe dry eye, such as Sjögren’s-related or graft-versus-host disease-related dry eye. “It seems to improve the ocular surface staining,” she notes.

• Exposure. “If the dry eye is being caused by exposure, you have to figure out exactly what the problem is,” notes Dr. Beckman. “If it’s an acute problem like a Bell’s palsy, where the patient can’t close her eye, that usually gets better over time. The patient may just need to tape her eyes closed at night and use a lot of lubricants. If it looks like this closure problem is more permanent, the patient may need a tarsorrhaphy or lid tightening, or a gold weight in the upper lid. In this situation, the solution is basically a mechanical repair. It’s like a rock in your shoe. You can put all the medicine you want on your foot, but if you don’t get the rock out of your shoe, you’re still going to have a problem.”

Getting Off to a Good Start

Surgeons offer these strategies to ensure the treatment you provide produces a positive result:

• Check for dry eye at every exam. “Many ophthalmologists only look for signs of dry eye when the patient complains,” says Dr. Akpek. “Tear film and ocular surface evaluation should be part of the slit lamp exam, and it should be documented. I’m not suggesting that everything needs to be measured in every patient, but checking the inferior tear meniscus and the tear-film breakup time at the slit lamp, even without staining the ocular surface, is free and only takes 60 seconds. Everyone who comes in for an eye exam should have the basic things examined, regardless of the reason for the exam.”

Some offices give all patients a questionnaire to elicit any symptoms of dry eye, but in many practices the staff or the doctor just ask patients directly. “Many offices will use a standard survey like the Standardized Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaire, or the Ocular Surface Disease Index questionnaire,” notes Dr. Beckman. “In my office our staff asks a series of questions to identify patients who are at risk or have symptoms. If the responses indicate that dry eye may be present, the staff will start the dry-eye workup.”

Dr. Akpek points out that any complaint about difficulty with vision should bring up some suspicion of dry eye, even if there are no significant ocular surface signs. “Dry eye has a lot of visual implications—it’s not just discomfort, burning and redness; it can really affect vision,” she says. “So every time a patient complains of anything relating to quality of vision, dry eye should be assessed.”

• Make sure patients know how to use whatever products they’re already using. “For example, some of our patients still use Lacrisert, the hydroxymethyl cellulose pellets that are inserted into the lower cul-de-sac to melt and provide dry-eye relief over a 24-hour period,” says Dr. Koffler. “Lacrisert has been around for several years and it’s still available; many patients swear by it. However, knowing how best to use it makes a big difference in whether it really works.

“It’s not the easiest thing to put in, and some people get blurring,” he continues. “In my experience, if we help the patient by offering suggestions such as putting it in at night, or wetting it initially to start the melting process, we can get a 70-percent compliance rate with this treatment. But if you don’t offer some suggestions and explain how to properly put it in, and, you’re not going to get a 70-percent success rate. So make sure your patients understand how to make the most of the treatments they’re using.”

• Individualize your treatment. Even when dry eye is noted, many surgeons use a blanket treatment approach. “A common mistake many ophthalmologists make is not taking the time to look into dry-eye signs and symptoms, because these are not interesting cases,” says Dr. Koffler. “It’s easy to come in and quickly prescribe a treatment or two without analyzing all the implications and possible causes of the problem. Not addressing the issue carefully can be a disservice to the patient, and may affect the outcome of other procedures.”

• Test every patient with severe dry eye for Sjögren’s. “Sjögren’s syndrome is very common and underdiagnosed,” notes Dr. Akpek. “It has severe implications for the future of the patient, so it should never be missed. Any patient who has bad dry eye, particularly significant staining of the conjunctiva with lissamine green, should always be tested for Sjögren’s.”

• Consider creating a “dryeye cheat sheet.” Because the list of causes that can lead to dry-eyerelated signs and symptoms is fairly long, Dr. Koffler suggests creating a “cheat sheet” listing all the possibilities, to help ensure you don’t overlook a possible explanation for the patient’s symptoms and your findings. “It’s easy to forget some of the possible explanations,” he notes. “The problem could be a medication the patient is taking, a blink problem, previous surgeries such as LASIK (which the patient may forget to mention), a meibomian gland issue, an autoimmune disease, an environmental problem, and so on. Having a cheat sheet could help prevent you from overlooking a likely source of the problem that needs to be addressed.”

Managing the Treatment

These strategies can help keep your treatment on the right track:

• Don’t overlook the impact of the patient’s existing medications. “Doctors often forget to consider the possible effects of medications a dryeye patient is already taking—especially when patients come in with a very long medication list,” notes Dr. Koffler. “However, it’s really important to know if a medication the patient is taking can cause dry eye. The problem could simply be that they’re taking an allergy medicine with antihistamine, an anticholinergic for their stomach, or an antidepressant that’s having an anticholinergic effect.

“In addition,” he says, “some patients who are already taking drops for their ocular discomfort could be having issues with those products, which may not even be addressing their real problem. I had a patient today who was having trouble with her drops; it turned out she had rosacea, meibomian gland disease and a secondary staph infection along the lid margin.”

There’s also the issue of whether the individual has been using the most appropriate drops up to now. Dr. Koffler points out that a general ophthalmologist seeing a patient about a dry eye for the first time should always ask about this. “Is it the tear that would be most helpful for this patient?” he asks. “Should you move the patient to a more balanced tear? Is the patient using a tear that contains preservatives every 15 minutes? If so, you’d better switch the patient to a preservativefree product. Of course, if the patient has already tried a variety of artificial tears, then you need to move on.”

Dr. Beckman points out that ocular medications can actually be contributing to the problem. “For example, it’s common to treat glaucoma with eye drops that can significantly contribute to dry eye,” he notes. “If your glaucoma patient has a dry-eye problem, consider other glaucoma treatment options such as SLT, and using preservative-free drops that might be a little more surface-friendly.”

• Consider using Restasis or Xiidra early on. “When Restasis first came out, doctors waited to prescribe it until the problem was pretty severe,” says Dr. Beckman. “They thought it was the kind of medication you only use on really advanced cases. In my experience, that’s not true. I think Restasis and Xiidra work better early on, before there’s too much damage, so I don’t hesitate to start a patient on them early in the disease.”

• Treat for signs, not just symptoms. “Some patients will have severe dry eye with minimal symptoms,” notes Dr. Beckman. “A patient who had a history of herpes in the eye may have a neurotrophic cornea and not feel the poor condition of the cornea, but you may find a lot of staining and scarring. So you have to factor in both the signs and the symptoms.”

• Don’t be too quick to move past artificial tears. “Even within the category of artificial tears, you have a tremendous range of choices to pick from, so you can probably stay in that treatment category for a little while,” Dr. Koffler points out.

• Remember that the patient may need multiple treatments. Dr. Beckman notes that many patients and doctors don’t appreciate that dryeye treatment often requires resorting to multiple options. “If a patient has an infection, you might give him an antibiotic and the infection is cured,” he says. “Dry-eye disease is more like glaucoma; sometimes you need multiple treatments to get the pressure down. Putting the patient on cyclosporine might make the patient 50 percent better, but to really get relief you may need to add something else, whether it’s punctal plugs or lifitegrast. Many patients and doctors don’t seem to understand that. Certainly the insurance companies don’t, because it’s very difficult to get them to cover a second drop. But the drops have different mechanisms, and they’re pretty symbiotic.”

Monitoring Progress

Once the patient is being treated, it’s important to stay on the case.

• Remember that treatment may improve signs before symptoms. Dr. Beckman notes that improvement in signs and symptoms doesn’t always happen simultaneously. “Sometimes I see an improvement in my findings, but the patient doesn’t note any improvement in her symptoms,” he says. “Patients may assume the medication didn’t work, when in actuality it is working; it just takes time for them to feel it. In my experience, almost all patients improve with treatment.”

• Don’t be too quick to switch treatments. “Usually, if someone comes to me and says he failed on one of these medications, it’s because he wasn’t on it long enough,” says Dr. Beckman. “Sometimes a doctor may not notice that the signs have improved—only that the symptoms didn’t improve. Patients may come in with corneal staining resolved and osmolarity and tear-film breakup time improved, but they still have severe symptoms, so the doctor decides to switch to a different treatment. That’s really not the best way to proceed. The patient just needs a little more time on the treatment, or the doctor needs to add something else.”

• On the other hand, be ready to back away from something that’s not working. “We can’t afford to get frustrated with a patient if the patient can’t tolerate the side effects of something we prescribe,” notes Dr. Koffler. “We tend to think that dry-eye products can’t really do any harm, but some of them are actually very irritating. Some can cause redness and burning, and some cause a bad metallic taste. If you’re sensitive to a preservative in one of them, you’ll certainly get allergy and redness and irritation. So don’t be surprised if a patient has difficulty with a particular treatment, and don’t blame the patient.”

Riding the Wave

Dr. Koffler notes that given the rapidly evolving nature of the field, it’s important to keep up with the current literature and the latest diagnostic and treatment-related developments. “New products continue to be developed,” he says. “There’s a very active research effort in dry eye, partly because any successful medication or device that makes it to market could become very profitable.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Beckman points out that dry eye and related conditions are still not being treated as much as they should be. “For the longest time dry eye was treated as a nuisance diagnosis,” he says. “There weren’t many treatments, or diagnostics to pick it up, so it was ignored. But today we see the impact it has on surgery outcomes and vision in general, so people are paying more attention. If you’re going to put someone in a multifocal lens, for example, you want to make sure the corneal surface is clear. Nevertheless, I believe dry eye is still underdiagnosed.” REVIEW

Dr. Beckman consults for Allergan, Novartis, Shire, Sun, TearLab, RPS, Bausch + Lomb and is medical director for EyeXpress. Dr. Akpek has received institutional research support from Allergan and Bausch + Lomb and is currently a consultant with Shire. Dr.s Koffler and Choi have no relevant financial interests.

1. Karakus S, Agrawal D, Hindman HB, Henrich C, Ramulu PY, Akpek EK. Effects of prolonged reading on dry eye. Ophthalmology 2018 Apr 25. pii: S0161-6420(17)33714-4. doi: 10.1016/j. ophtha.2018.03.039. [Epub ahead of print]