Recently, I conducted a review of the existing literature, along with my co-investigator, Charlie Abraham, MD, regarding the impact of early and more advanced glaucoma on a patient's day-to-day visual functioning. Our goal was to get an idea of what level of glaucoma damage would first cause patients to report a decrease in quality of life.

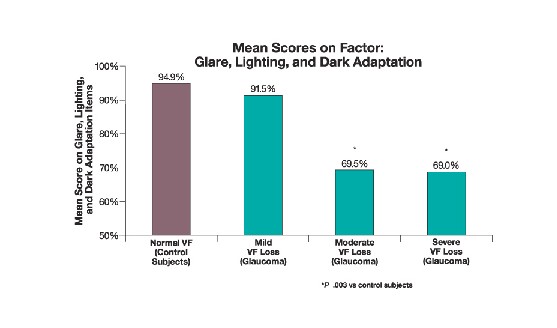

The results were surprising. We found that patients report reduced quality of life at much lower levels of glaucoma damage than popularly believed. Patients with only mild, unilateral glaucomatous damage reported negative changes; even some newly diagnosed glaucoma patients with early or moderate damage notice loss of visual function. For example, in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS), at enrollment, more than 25 percent of newly diagnosed glaucoma patients reported blurred vision, difficulty in adapting between light and dark environments, trouble seeing in the dark, and problems with bright lights.1

Another group of researchers found a correlation between complexity of treatment and lower quality of life.2 This raises the possibility that the treatment itself may contribute to degradation of the patient's quality of life—something that would probably not be reflected in objective test results. (In fact, a study I participated in while a fellow at Georgetown University, which I presented at ARVO in 1996, revealed that patients complain of more symptoms of depression, headache and gastrointestinal upset with greater glaucoma therapy. This was especially true with beta-blockers and pilocarpine.)

|

| Glaucoma patients' quality of life scores decrease with mild visual field loss and worsen as loss increases. |

Like most ophthalmologists, I used to focus primarily on keeping a glaucoma patient's intraocular pressure at a safe level. Our study, however, convinced me of the importance of monitoring the patient's subjective experience to uncover changes in the patient's quality of life. As a result, I ask my glaucoma patients to fill out a questionnaire that reveals how their day-to-day life is being affected by the disease.

This is a departure from the way most of us have traditionally managed glaucoma, but it's been helpful for both me and my patients in a number of significant ways.

Getting to the Patient's Bottom Line

Why is questioning the patient about quality of life so important?

• Quality of life is the concrete, bottom-line issue for the patient. Quality of life is what the patient wants. If you keep IOP down but the patient is unhappy because daily living has become more difficult, everybody loses.

The objective (and somewhat paternalistic) approach we often use when treating glaucoma patients is a far cry from the way we manage many other visual problems. When deciding whether or not to remove a cataract, for example, it's not sufficient for the cataract to meet certain objective criteria—the patient also has to be complaining. We don't rate the cataract on a scale of one to 10 and announce that it has to come out.

Getting a subjective report from the patient makes perfect sense, and it's an approach that should be applied to other diseases, including glaucoma.

| Studies Using Survey Instruments Targeting Quality of Life Issues Related to Vision | ||

| Survey Instrument | Description of Instrument | Findings in Glaucoma Patients |

| The Activities of Daily Vision Scale (ADVS) | Twenty items (visual activities) with five subscales of visual function (daytime driving, night driving, near vision, distance vision, glare disability) | 1. Significantly lower (worse) ADVS scores for glaucoma patients than for normal controls.2 2. Significant correlation between lower QOL scores and increased visual field loss, decreased visual acuity, and increased complexity of therapy.2 |

| The National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) | Fifty-one items with 13 subscales of visual function (near vision, peripheral vision, distance vision, driving, color vision, ocular pain, role limitations, dependency, social function, mental health, expectations, general health, general vision) | 1. Lower (worse) NEI-VFQ scores for glaucoma patients than for normal controls.3,5 Glaucoma patients scored significantly worse than controls (P<.05) on general vision, distance vision, near vision, role limitations due to visual disability, driving, ocular pain, and mental health.3 2. More severe field loss in the better eye,3 or binocular field loss5 was associated with a decrease in QOL scores. |

| VF-14 | Fourteen items measuring patient difficulty with 14 vision-related activities such as driving, reading print of various sizes, and recognizing people | 1. Lower (worse) VF-14 scores for glaucoma patients than for normal controls.3,5 2. Even mild visual field loss was associated with a decrease in VF-14 scores.3 3. More severe field loss in the better eye3 or binocular field loss5 was associated with a significant decrease in VF-14 scores. |

| Visual Activities Questionnaire (VAQ) | Thirty-three items with eight subscales of visual function (glare disability, light and dark adaptation, acuity and spatial vision, visual search, visual processing speed, depth perception, color discrimination, peripheral vision) | 1. VAQ total and VAQ peripheral vision subscale scores were significantly correlated with greater visual field loss in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients.1 |

| Glaucoma Quality of Life-15 (GQL-15) | Fifteen items with 4 subscales of visual function (central and near vision, peripheral vision, glare and dark adaptation, outdoor mobility) | 1. Overall scores on the GQL-15 were significantly lower for glaucoma patients than for control subjects.4 2. Even patients with mild (unilateral) field loss had decreased GQL-15 scores.4 3. More severe field loss was associated with lower GQL-15 scores.4 |

• Even early glaucoma can undermine quality of life. In my experience, most ophthalmologists believe that if a glaucoma patient doesn't have advanced disease or partial blindness, normal living isn't affected to any noteworthy degree. I believed this myself, until we completed our review and I began surveying my own patients about their quality of life.

In fact, quality of life can be significantly reduced by very early stage glaucoma. This means our patients may need more help than we're giving them. (See "The Impact of 'Minimal Damage.' " )

Why should this be the case? It's easy to forget that a small nasal scotoma in a visual field is simply the first evidence of an underlying problem that's affecting the nerve and retinal ganglion cell layer. Those other, undetected changes can interfere with spatial orientation, contrast sensitivity and other important visual functions. Glaucoma-related vision problems aren't limited to loss of acuity or peripheral vision, and damage is almost certainly occurring before it becomes evident in traditional test results.

• Quality of life is subjective. Our goal in treatment is supposed to be both the prevention of blindness and the preservation of quality of life. But while blindness is easy to define, everybody's life—and everybody's idea of what's important—is different. How can you preserve your patient's quality of life without knowing what that means to the patient?

For example, two patients with the same level of glaucomatous damage may have their quality of life impacted in totally different ways. If one 65-year-old is retired and sedentary, a reduction in spatial orientation and contrast sensitivity may not affect quality of life the way it would for a similar patient who is employed and active.

• Changes in quality of life aren't always reflected in traditional test data. Glaucoma can undermine a patient's quality of life in significant ways that we can't always deduce from exam results. A patient may present reporting a decline in their vision, and yet our tests don't show any change. Most of us would say, "Everything's the same, I'll see you in another three months." This is frustrating for the physician, and even more so for the patient because we didn't do anything in response to the complaint.

By assessing the patient's quality of life using a questionnaire, we get specific information about how the patient's daily life is being affected by the disease (and possibly by the treatment). Monitoring this can tell us when a general complaint reflects a real change for the worse—regardless of what the test results appear to say.

• More information means more appropriate treatment. Knowing how the patient's quality of life is being affected has given me a much better sense of whether more aggressive (or different) treatment is needed. As noted before, two patients with the same objective symptoms may need different levels of treatment because of the different ways their quality of life is being affected. Treatment that's more appropriate to the individual's needs means happier patients and better results.

• Questioning the patient about quality of life issues educates the patient. Thinking along these lines changes the way patients gauge the progress of the disease. They can easily misdiagnose a loss of function as being the result of aging or other causes. Once they realize that changes in day-to-day function may be related to glaucoma, they won't dismiss them as inevitable, and they'll seek treatment. They will also provide you with better information about their status and ask better questions during their exam.

• A patient who understands the day-to-day consequences of worsening glaucoma is more likely to be compliant. The questionnaire presents the possible effects of untreated glaucoma in a very concrete way. That can make patients a lot more conscientious about following your recommendations.

Creating a Questionnaire

In the review we conducted, we looked at the results of five different surveys, all consisting of about 15 quality of life questions. (See chart above.) Each survey asks about tasks that patients manage during a typical day. Do they trip on the sidewalk? Do they have trouble recognizing faces across the street? The patient may be asked for a yes or no reply, or asked to state to what degree the task is a problem.

I chose to design my own questionnaire, using questions that I thought were particularly relevant to my practice and patients. Some were based on questions in the other surveys; some were original. (If you choose to design your own questionnaire, remember to keep it simple enough that the patient can fill it out while sitting in the waiting or exam room.)

Here's the questionnaire I created for my glaucoma patients to fill out. On the form, each question is followed by four possible answers (never, rarely, sometimes, often).

Do you have difficulty with:

1. Reading newspaper print?

2. Recognizing faces?

3. Seeing objects coming from the

side?

4. Tripping over objects?

5. Walking up/down stairs?

6. Seeing at night or in the dark?

7. Adjusting to dim light?

8. Crossing the street?

9. Reading signs when driving?

10. Judging distance when grasping

for objects?

We create an overall numerical score by rating the answers from 0 to 3, where 0 equals never.

Once the patient has completed the questionnaire, all you have to do is scan it or have one of your technicians add up the points. The initial results for a given patient become the baseline; then you can compare the answers—or just the overall score—at future visits to see how the patient's quality of life has changed over the course of time or treatment.

| The Impact of "Minimal Damage" |

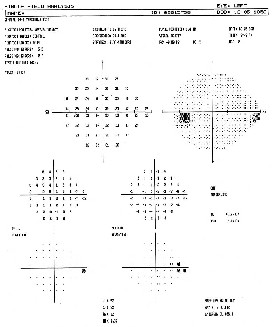

|

| Traditional test results can be a poor basis for judging how glaucoma is affecting a patient's quality of life. For example, ophthalmologists tend to assume that minimal damage in one eye, noted in a visual field, doesn't produce any functional vision loss or have a significant impact on a patient's quality of life. We assume that the other eye will compensate for a small defect. During presentations, I often display the visual field shown at left, from a 50-year-old female patient with no cataracts or other pathology. The field reveals a small nasal scotoma that had appeared since this patient's previous visit. Given that the other eye's visual field didn't show any problem, ophthalmologists at my presentation usually agree that this wouldn't cause a reduction in quality of life for the patient. This patient's quality of life survey responses, however, indicated that she had begun experiencing decreased night vision and was having difficulty driving because she had lost some of her ability to perceive signs. Two points should be clear: First, traditional test data—and traditional assumptions—are not an accurate barometer of how a patient's quality of life is being affected by glaucoma. Second, a decrease in quality of life can start much earlier than most of us have believed. |

Why Not Just Ask?

Of course, it's possible to uncover this kind of information by interviewing the patient. Unfortunately, inviting patients to tell us about the problems they are having in daily living will often trigger a lengthy, rambling reply, which is totally impractical when you're seeing 40 or more patients a day and have 12 patients seated in the waiting room.

If you want to check the patient's quality of life, a questionnaire is quick and to the point. (You can ask more detailed questions based on the responses you get to the questionnaire.)

The one time I skip the questionnaire and take the patient's history myself is when first meeting with a new glaucoma patient. Among other things, this gives me the opportunity to educate the patient about the disease, instead of just handing out a brochure or letting the technician talk to the patient. (Focus groups have revealed that most patients feel shortchanged in this respect.)

Doing this takes extra time, but it pays off in many ways. Patients remember the initial visit, and the positive impression they have of me and our practice lasts for years.

A Change Worth Making

So far, there isn't sufficient clinical data to demonstrate conclusively that quality of life questionnaires alter treatment and produce better outcomes. Nevertheless, it's clear that having patients fill out such a questionnaire carries a host of potential benefits. Doing so has certainly changed my approach to treating glaucoma for the better.

The moral of the story? Test results are invaluable, but the only way to know for sure what's really going on is to ask the patient.

Dr. Bournias is director of the Northwestern Ophthalmic Institute and assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago.

1. Janz NK, Wren PA, Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE. Quality of life in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients: the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology 2001;108:887-897.

2. Sherwood MB, Garcia-Siekavizza A, Meltzer MI, Hebert A, Burns AF, McGorray S. Glaucoma's impact on quality of life and its relation to clinical indicators. A pilot study. Ophthalmology 1998;105:561-566.

3. Gutierrez P, Wilson MR, Johnson C, et al. Influence of glaucomatous visual field loss on health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:777-784.

4. Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, et al. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma 2003;12:139-150.

5. Parrish RK 2nd, Gedde SJ, Scott IU, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:1447-1455.