Though you'll most likely be successful with your LASIK procedures, the occasional case of epithelial ingrowth or striae will crop up to hound you at the clinic. Here's a review of several surgeons' favorite methods for handling common complications of LASIK, as well as complications that may not occur as often but which surgeons say you should be prepared for.

Epithelial Ingrowth

The rate of this complication varies from around 1 to 12 percent in primary cases,1,2 but its incidence can jump to between 10 and 40 percent in retreatments,3 so experts have honed their responses to it.

"The first thing to consider with ingrowth is when it's happening—whether it's sooner or much later," says

In cases of recurrent ingrowth, Boston surgeon Samir Melki will suture the fistula, in addition to placing other sutures around the edge flap.

"If you see little islands of epithelial cells not connected to the edge of the flap, this is more epithelial implantation than ingrowth," Dr. Melki continues. "These cells were implanted during LASIK, rather than growing from the outside toward the interface. We watch these nests and they usually resolve. For cells that are connected to the edge of the flap, follow them, using fluorescein staining. If you see staining at the edge, that means there's a fistula there, and such a patient needs to be followed more closely than someone with no fistula. We also try to assess the speed at which the cells grow; some are slow so we see the patient every week or every month, while some are fast, and the patient needs to be seen in a matter of days."

Los Angeles

"In our practice, we've found that the ingrowth develops in the first couple of days after LASIK but the cells aren't visible until about three weeks postop," he says. "It's at that time these eyes develop some epithelial pearls and signs of ingrowth. I don't think it gets worse, though. So, we see everyone at about three weeks postop. If the ingrowth is there and significant, we'll treat it. If it's not present, we're confident it won't ever be."

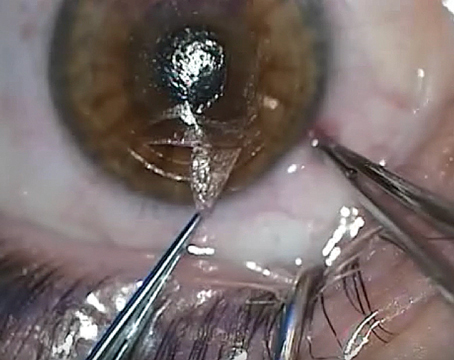

Scraping the ingrowth is the procedure of choice for surgeons who decide it's time to lift the flap. "When we decide it's time to do something, we lift the flap, scrape the bed and the backside of the flap with a spatula or dry methylcellulose sponge," says Dr. Melki. "I try to avoid performing retreatments at the same time as a scraping unless the ingrowth is peripheral, since sometimes the ingrowth, if close to the visual axis, may be the cause of the postop refractive error; when you remove the ingrowth, the error is gone.

"If scraping doesn't work, as a second-stage treatment I'd suture the flap with about seven sutures, leaving the hinge without a suture. This ties the flap down and prevents the cells from growing. I may also put an additional two or three sutures in a quadrant where the cells are growing into the interface. This is because sometimes if you lift a flap it becomes edematous, providing a gap that may allow cells in."

Dr. Maloney also likes suturing as a second stage for recurrent ingrowth. "The key to suturing the flap is stretching it out so it's in the proper position," he says. "So, I use five sutures for that, one opposite the hinge and two more on each side of that one, evenly distributed. These sutures have to be unusually tight. Not making them tight is a frequent mistake. They have to be this tight because they tend to cheesewire and loosen significantly over the space of a month, allowing epithelium to grow in. The flap should look tight as a drumhead when you're done." Like Dr. Melki, he also puts several sutures in the area of the fistula to seal it off. He adds that the use of Tisseel corneal glue as described by Minneapolis surgeon David Hardten is also an option, but that, in his hands, when he uses the glue he often winds up having to use sutures anyway.

Flap Folds

Surgeons say if the folds are microstriae, they're usually not visually significant and can be left alone. However, they're quick to add that it pays to be aggressive with macrostriae.

"If they're visually significant, I believe you have to take the patient back to the OR—in a sterile environment, under the microscope and with the speculum in—in order to take care of them," says Renato Ambrosio Jr., MD, of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. "You can't play with them at the slit lamp, as I'm worried about infection and other issues that could occur there.

"To smooth them, I first apply four or five anesthetic drops, then use a Sinskey hook to find the edge of the flap, then use a very fine flap spatula to gently lift it" he says. "I apply a hypotonic solution, half balanced salt solution/half sterile water, to expand the flap. I then moderately wet a Weck-Cel sponge and smooth the flap with it. If you put in too much water, the sponge will be mushy, but a little less water keeps it firm so you can apply pressure to the edge."

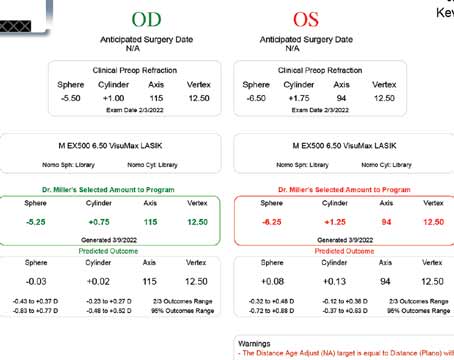

For tough folds, or long-standing folds in patients that are referred to him, Dr. Ambrosio has taken to using a surface treatment with the excimer laser. "For folds that are long-term postop, I know they're not going to be treatable with sutures, so I'll go in and do a topography-guided ablation. These patients usually have some amount of astigmatism or sphere that you can treat and get rid of the folds in the process. If they don't have a refractive error, you can use the laser in a PTK mode that's refractively neutral."

Unusual Situations

Dr. Maloney says he's published data on two other complications that can occur with LASIK. Though rare, he says it's important you catch them if present, because mistreating them can actually cause bigger problems.

"Some patients can get central toxic keratopathy, a white opacification of the central cornea," Dr. Maloney says. "It's confusing because it can look like infectious keratitis, so it's important to inspect the site for inflammatory cells. If there are cells, then you know it's infectious. CTK is very rare, but can cause a hyperopic shift and striae that resolve over six to nine months. The key is to not treat it, because steroids won't help and can cause a rise in intraocular pressure. Also, lifting and scraping don't help because the CTK is deep in the stroma.

"The other entity we described is interface fluid after LASIK caused by a high IOP," he adds. "In this condition, fluid collects in a potential space under the interface and creates a fluid-filled pocket. This causes a problem when you check the pressure with Goldmann tonometry, because the tonometer will measure the pressure in the pocket rather than the IOP. The pocket pressure might be 2 or 3 mmHg while the eye is 40 mmHg. We've seen several patients with significant visual loss when this has gone undiagnosed, so it's important not to use steroids for more than a week or so postop. And, if patients are on long-term steroids, watch for interface fluid. When in doubt, check IOP in the peripheral cornea using a Tonopen."

1. Wang MY, Maloney RK. Epithelial ingrowth after laser in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;129:6:746-51.

2. Wygledowska-Promienska D, Rokita-Wala I. Epithelial ingrowth after LASIK—personal experience. Klin Oczna 2003;105:3:157-61. (Polish)

3. Chan CC, Boxer Wachler BS. Comparison of the effects of LASIK retreatment techniques on epithelial ingrowth rates. Ophthalmology 2007;114:4:640.