Avoiding unexpected and unwanted results of refractive surgery can be just as important as striving to achieve ideal visual outcomes. More surgeons are coming to appreciate this today.

“I haven’t had a postop case of ectasia in seven years,” says Scott MacRae, MD, director of refractive services in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Rochester. “This problem is so rare because we’ve gotten to be so good at screening these patients.”

Dr. MacRae and other leading surgeons have learned that the key to steering clear of ectasia and other postop problems lies in how they approach the initial preop visit—specifically, how well they scrutinize the cornea, using corneal topography, keratometry, pachymetry and old-fashioned examination techniques. Here, they share strategies for selecting the right patients for surgery and the right surgical modality.

Getting Involved

“Preparing for refractive surgery is much more involved than doing the actual procedure itself,” asserts Kendall E. Donaldson, MD, MS, professor of clinical ophthalmology, cornea/external disease/refractive surgery at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. “I’m not suggesting that refractive surgery, which needs to be carefully learned and perfected, is easy. But you have to spend more time on preop planning, evaluating all of the factors that could rule in or rule out surgery. We spend a few hours providing our fellows with instruction on surgical technique. But many more hours are spent on preop preparation.”

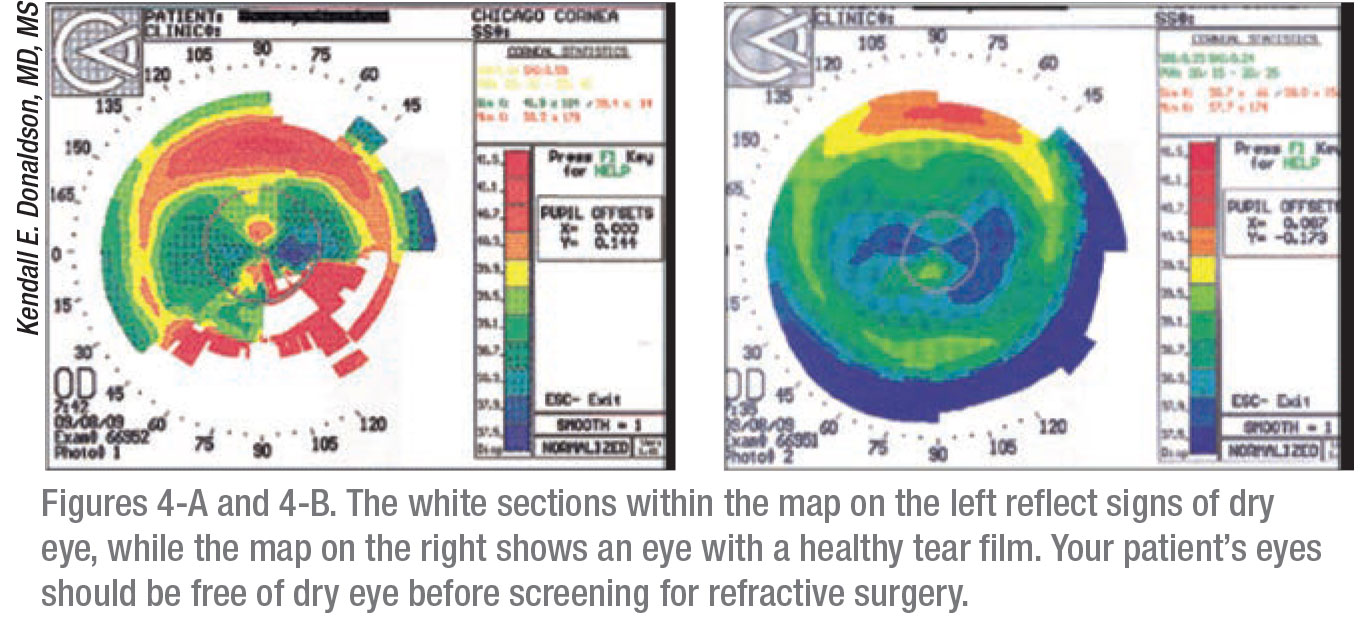

Before preop screening can even begin, however, Stanford University’s Edward E. Manche, MD, prioritizes the need to optimize the ocular surface. “You have to make sure you’re imaging an eye that’s healthy,” he says. “The ocular surface needs to be pristine, unaffected by meibomian gland dysfunction, evaporative tear disorder, punctate epithelial erosions or other signs and symptoms of dry eye. Perform tomography and topography only after you’ve treated any of these conditions successfully. Sometimes, patients are also affected by corneal warpage related to contact lens wear. If so, instruct them to not wear soft contacts for a week before their screenings. For torics, have them go two weeks or a month. For RGPs, definitely a month. And for Ortho K, several months are needed to get the corneas into normal shape.”

Dr. Manche’s techs work up a history on the patient to address all issues. “We scan the patients, and I try to correlate abnormalities with the scans,” he notes. “The way our clinic works, when I go in to see the patient, I want to do so with all of the data in front of me. Otherwise, it doesn’t make for a good flow.”

|

Custom Fit Screening

Dr. MacRae meets the preop challenge by making sure he uses a screening instrument that best fits the needs of each case. He relies frequently on an Orbscan (Bausch+Lomb), which works well for many patients. But if a patient has astigmatism or presents as a potentially complicated case, he switches to a multi-modality Galilei (Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems), which he has access to at the Flaum Eye Institute in Rochester.

Unlike the Orbscan, Galilei images the anterior and posterior cornea, Dr. MacRae says. “But the most helpful part of the Galilei is that it has a toric component, so that allows you to compensate for patients with astigmatism,” he observes. “The posterior float on the Orbscan can’t be used to accommodate astigmatism, anteriorly or posteriorly, because it conducts a best-fit-sphere analysis. So with the Galilei, patients who would otherwise be excluded from consideration for refractive surgery are now included.”

|

The Galilei also combines diverse state-of-the-art technologies—such as placido topography, dual Scheimpflug tomography and optical biometry—to offer a complete solution for refractive surgery planning. “All measurements are included in one device,” he notes. “The device has also been found to be highly sensitive and specific in detecting keratoconus and forme fruste keratoconus.”

Probabilities and Validation

Dr. Manche uses the placido-based Atlas 9000 Corneal Topography System (Zeiss) and Pentacam tomographer (Oculus) when screening potential refractive surgery candidates. The Atlas includes PathFinder II corneal analysis software, which provides probabilities for five corneal conditions by comparing topography exams to an extensive clinical database. Validation of PathFinder II with an independent data set has demonstrated greater than 90-percent sensitivity, specificity and accuracy in detecting normal versus abnormal corneas, he says. Color-coding of PathFinder II parameters also shows him when parameters are beyond normal limits and may contribute to specific classifications.

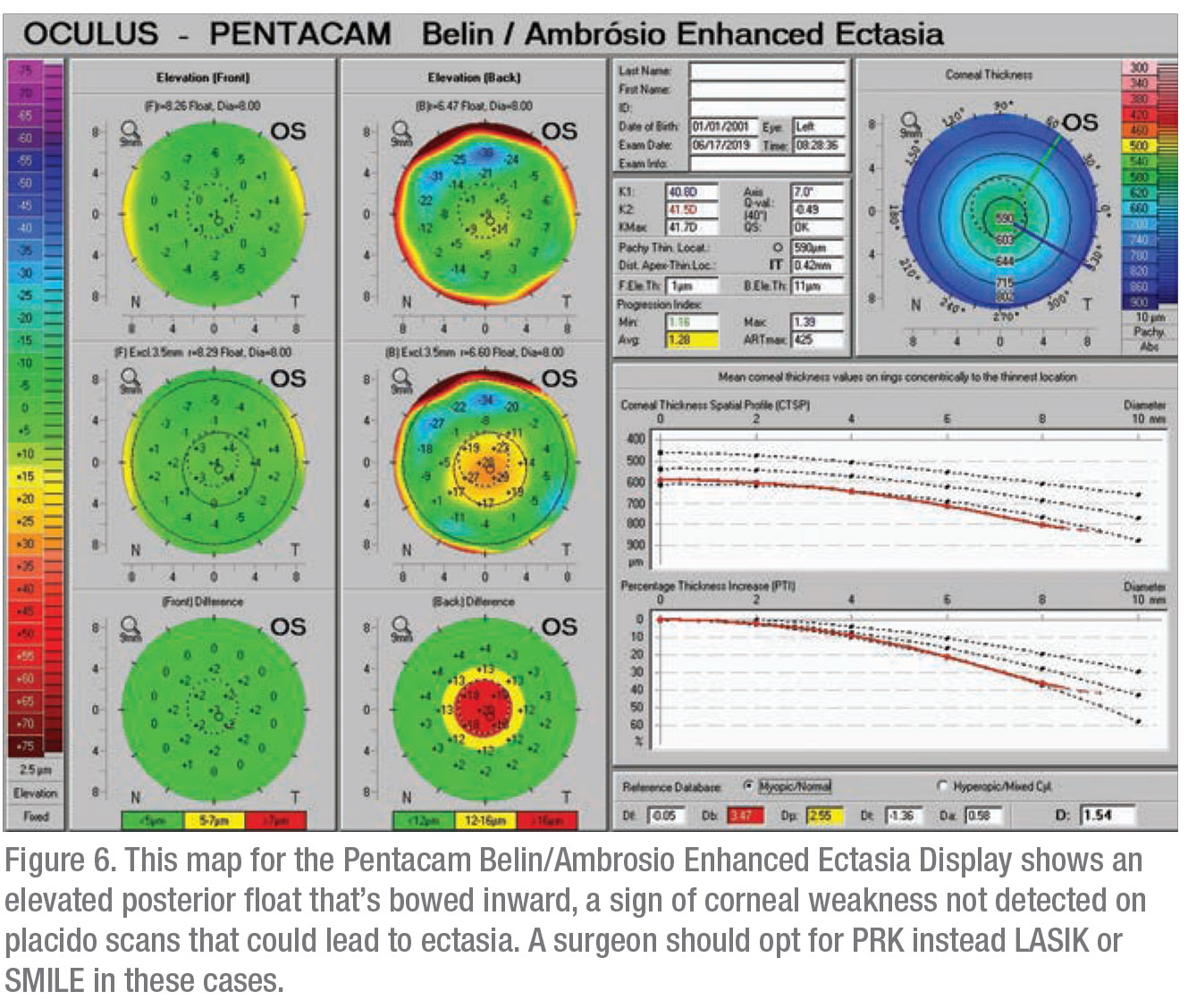

“I’m a data hound, so I will get placido disc readings from the Atlas and the Pentacam,” he says. “The Pentacam tomography map shows anterior and posterior elevations. I may see an indication of risk—that the patient is susceptible to ectasia, for example—based on the findings in the posterior area. In the Belin/Ambrosio Enhanced Ectasia Display embedded into the tomographer, you can see the summary data. If there are abnormal posterior or anterior findings, it can help determine if a patient is not a candidate for surgery. On the difference map, depending on the patient, you’ll see white (proceed), yellow (some posterior deviation) and red (extreme risk of ectasia in the posterior wall.) So the testing allows you to ensure safety and rule out a patient based on extreme risk of ectasia.”

Screening Principles

|

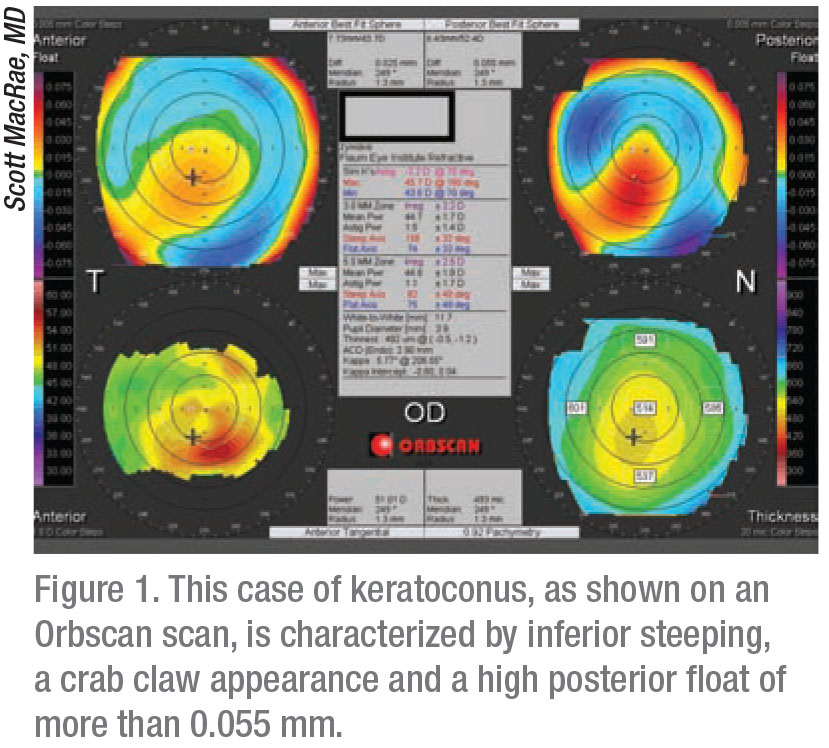

Dr. MacRae recommends applying some basic principles when screening all patients. “I do about 1,000 refractive surgery cases per year,” he says. “We screen using the criteria most people use. If the posterior float is exceptionally high—more than 40 mµ on the Orbscan—that raises a red flag. For marked skewing, asymmetry, or marked thinning (less than 450 mµ), I’m concerned about that from the beginning.”

Dr. MacRae uses the “60-percent rule” to ensure he has enough corneal thickness with which to work. “At 600 mµ of corneal thickness, for example, 60 percent would be 360 mµ. So you can do a flap that is 100 microns deep. That means 140 mµ would be the deepest ablation you could do with LASIK because that would bring you to 360 mµ of residual tissue, or 60 percent of the corneal thickness.

Knowing this during screening can help you determine whether to perform PRK or LASIK, depending on refractive needs.”

A high myope, such as -8 D, may push him toward recommending PRK only, he says. “For a 450-mµ cornea that’s perfectly symmetrical, patients are usually safe candidates if they need only 1 or 2 D of treatment,” he notes. “These patients can usually do well with PRK. You don’t want to overreact to the 60-percent rule.”

Another basic principle to consider is making sure your corneal topographer is at the right setting. Dr. MacRae says some surgeons choose a setting that’s too sensitive. “I set my Orbscan setting at 1 D,” he notes. “Others may put it at a half of a diopter, thinking that’s better. Then, all of a sudden, they’ll see these colors starting to stand out on the scan. Some experts, such as Steve Klyce, MD, recommend a setting as high 1.5 D.”2

|

Tertiary Approaches

Dr. Donaldson offers pointed preop screening advice based on her work in a tertiary practice that receives many refractive surgery referrals. “We benefit from insights on the many factors that might rule out surgery—more so than the typical surgeon would in private practice,” she notes. “My experience can help all surgeons keep in mind what to look for, even if 90 percent of their cases are good candidates, such as a 30-year-old with a -3 D sphere. ODs do 75 percent of our screening, so we never see bad patients. But we need to screen further before deciding how to proceed.”

Dr. Donaldson relies on corneal topography, corneal tomography, keratometry, pachymetry and a thorough exam when screening her patients. Here are some important considerations she recommends keeping in mind:

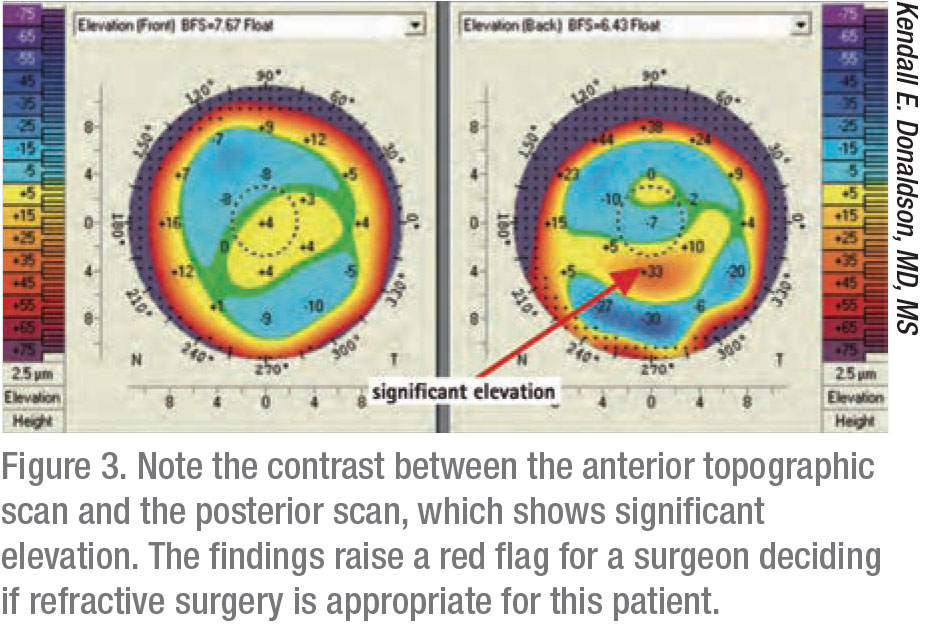

• Anterior elevation map: Consider using keratometry to evaluate the shape of the cornea, looking for astigmatism and symmetry. “The corneas should be symmetrical,” she says. “Any elevation steeper than 47.2 D is a red flag. You need to investigate for keratoconus.” She also investigates when the manifest astigmatism in the patient’s ophthalmic lens prescription doesn’t match what she sees in topography. “The cause could be lenticular astigmatism,” she points out. “Or it could involve some other situation that would make us think twice before proceeding with a procedure.”

• Posterior elevation map: “Again, we’re looking at the keratometry numbers and the shape—this time from the posterior perspective,” says Dr. Donaldson. “The posterior aspect should match the anterior aspect. Anything that doesn’t match is also a red flag for us.”

• Pachymetry: “Any measurement of the cornea that is below 470 microns is a red flag,” says Dr. Donaldson. “We are also looking for thin points. If the center of the cornea is too thin or you find thinness within a radius of 0.5 mm from the center, that should also raise a red flag.”

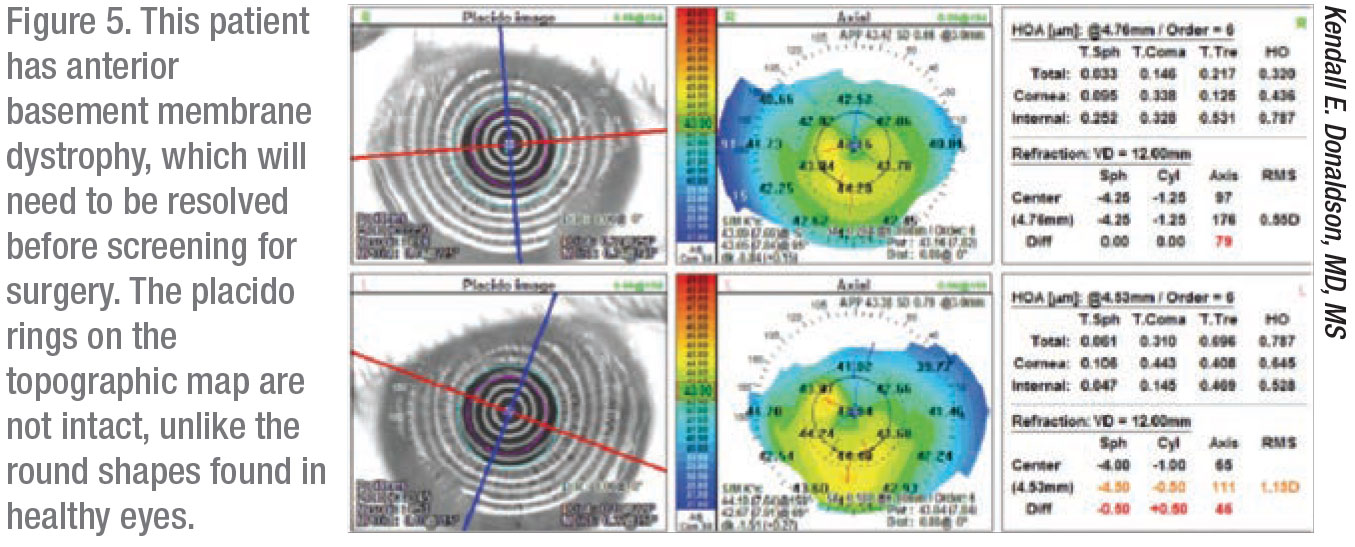

• Underlying pathology: “We make sure we check for ocular surface disease, anterior basement membrane dystrophy, and (as mentioned previously) keratoconus,” says Dr. Donaldson.

|

Guarding Against Risks

Dr. MacRae offers this advice to avoid surgical risks: “If you see a marked red zone inferiorly, nasally or temporally, that’s another red flag, another sign of what we call skewing, where the bow tie is bigger down below than above,” he says. “This represents a clear-cut case of keratoconus. No surgery can be done on this patient.”

In a patient with Salzmann’s nodular degeneration, a topographical representation of the cornea will reveal significant irregular astigmatism, another concern, he says.

|

If Dr. Manche encounters a subtle abnormality, he considers using PRK instead of LASIK. “It’s also possible we’ll choose IOL surgery,” he notes. He also remains vigilant whenever his screening exam turns up two other key findings:

• A steep or a posterior slope that’s bowed in. “Some people say the earliest sign of keratoconus is a bulge on the posterior cornea,” he notes. “You might also see the anterior cornea bowed forward.”

• A view going from the central to the peripheral cornea that reveals several suggestive indices, including those associated with thinning.

Pulling It All Together

In summary, Dr. Donaldson advises all refractive surgeons to keep the potential outcome of every case in mind. “When you’re screening a patient for an elective procedure, you want to be extra careful and err on the conservative side,” she says. “We have to ask ourselves: How well am I going to make this patient see? Am I going to flatten the tissue too much? Is the cornea too thin? Will underlying conditions cause long-term distortion?

“We want to keep them in the normal range of corneal fitness,” she continues. “Remember to always calculate preoperatively what their corneas will look like postoperatively. We’re looking at how LASIK will affect patients tomorrow and 10 years from now.” REVIEW

Dr. Donaldson reports financial relationships with Alcon, Allergan, Johnson & Johnson Vision, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Bausch + Lomb, Kala Pharmaceuticals, EyeVance, Lumenis, Omeros and Carl Zeiss Meditech.

Dr. Manche is a consultant for Allergan, Avedro, J & J Vision and Carl Zeiss Meditec. He performs sponsored research for Allergan, Alcon, Avedro, Carl Zeiss Meditec and Presbia. He owns equity in Vacu-Site and RxSight. Dr. MacRae reports no financial relationships with relevant companies.