When managing a disease or condition, knowledge is power. But how do you manage a condition when your knowledge about its origin and mechanism is incomplete? This is the challenge of managing aqueous misdirection which, though rare, is one of the most serious complications of intraocular surgery.1 Though experts still theorize about the condition’s ultimate cause, they say that, if you’re prepared for it and respond quickly, you can successfully manage cases of aqueous misdirection. In this article, physicians discuss this rare postoperative complication and share their approaches to treating it.

The Disease’s Mechanism

The condition has been called several names, including ciliary block glaucoma and malignant glaucoma, derived from various theories of disease etiology, but its precise origins are unknown.

“Malignant glaucoma can be very hard to control and can seriously affect vision if not reversed quickly,” says Marlene Moster, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University School of Medicine and attending surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. She says there are several theories about the mechanism of aqueous misdirection, such as a combination of weak zonules and posterior pressure leading to axial shallowing of the anterior chamber and closure of the angle. Another is the choroidal expansion theory, which postulates that eyes prone to choroidal expansion—even a minimal expansion of 50 µm—will cause intraocular pressure to rise dramatically. Even with a peripheral iridectomy in place, the lens-iris diaphragm continues to move forward.

“What’s agreed upon at this point is that aqueous misdirection is related to an abnormal relationship between the lens, vitreous and ciliary body that results in forward displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm,” says Natasha Kolomeyer, MD, a glaucoma specialist at Wills.

In a healthy eye, the aqueous percolates through the vitreous to the posterior chamber and then out through the trabecular meshwork, explains Dr. Moster. “But with aqueous misdirection, the vitreous is hydrated and aqueous fluid can’t easily pass anteriorly through the gel,” she says. “You end up with a blockage of aqueous behind the vitreous, and this establishes a vicious cycle where the aqueous can’t get out, the vitreous keeps moving everything forward and the intraocular pressure continues to rise.

“What we don’t know is why previous glaucoma surgery makes a patient more at risk,” she adds. “We only know that it changes the equilibrium of the eye. But if that’s the case, why don’t we see it more frequently?”

An Uncommon Complication

Studies have reported an aqueous misdirection incidence of 0.5 to 4 percent—closer to 2 percent after glaucoma surgery.2,3 “The glaucoma service at Wills Eye Hospital sees this about five to 10 times a year,” says Dr. Kolomeyer. “But we’re a tertiary care center with an emergency room, so this is likely a biased sample.”

Steven J. Gedde, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, agrees that it’s a fairly rare complication. Citing the on-going PTVT Study, a multicenter, randomized clinical trial of 242 eyes of 242 patients undergoing primary tube versus trabeculectomy surgery (See “What We’re Learning from the PTVT Study” in the October issue), he says the incidence of aqueous misdirection in the tube shunt group was 3 percent and in the trabeculectomy group, 1 percent. “That gives you an idea that this is a relatively uncommon complication,” he says.

The unexpected nature and urgency of the disease are what make it a challenge to treat, says Dr. Kolomeyer. While the disease typically presents as an early postoperative condition, usually after glaucoma surgery, she notes that it can happen after other types of intraocular surgery, and in some cases it can crop up years later. “Other cases have occurred without any prior laser surgery, such as after trauma or the use of miotics,” she says.

Dr. Gedde says quickly recognizing the symptoms can make a big difference in treatment outcomes. “Aqueous misdirection has a very characteristic appearance,” he says. “There’s axial shallowing of the anterior chamber not only peripherally, but centrally as well, due to posterior pressure.”

Make note of the lens-iris position, cautions Dr. Moster. She says this may be the tip-off that aqueous misdirection is occurring. Additionally, she notes that the forward movement may push the lens dangerously close to the cornea.

|

Risk Factors

Patients may be anatomically predisposed to aqueous misdirection, since those who get aqueous misdirection tend to be those who already have glaucoma. Dr. Kolomeyer says hyperopia, smaller eyes, a history of peripheral anterior synechia and eyes with a propensity to have choroidal expansion or reduced vitreous conductivity are more at risk.

Dr. Gedde notes that aqueous misdirection most often occurs in patients who have chronic angle-closure glaucoma or a history of glaucoma or aqueous misdirection in one eye. “Those with a history of angle-closure tend to have more crowded anterior segments, shallower chambers, and larger lenses to begin with. Those eyes seem to be more predisposed to this complication,” he says.

Diagnosing the Disease

“A shallow anterior chamber is the first thing to look for,” says Dr. Kolomeyer. “But several other conditions have this feature too.” Pupillary block, suprachoroidal hemorrhage and annular ciliary choroidal effusion are also accompanied by shallowing of the anterior chamber.

“It’s a diagnosis of exclusion,” says Dr. Gedde. “In order to diagnose aqueous misdirection or malignant glaucoma—whatever term you use—you really do need to have a patent peripheral iridectomy to rule out pupillary block.”

“If there’s shallowing of the chamber and increased pressure due to pupillary block, an iridectomy will immediately deepen the anterior chamber,” explains Dr. Moster. “Then your diagnosis is pupillary block and not malignant glaucoma.”

For ruling out choroidal effusion, Dr. Gedde says you can do ultrasound biomicroscopy to check for the characteristic fluid in the suprachoroidal space under the ciliary body. An anterior segment ultrasound biomicroscopy to check for anterior rotation of the ciliary processes can also help make the diagnosis, says Dr. Moster. “Anterior rotation of the ciliary processes is very suggestive of malignant glaucoma because it indicates that there’s a force pushing everything from behind,” she notes.

“I generally associate aqueous misdirection with high intraocular pressure,” Dr. Gedde says. “However, aqueous misdirection doesn’t always present with elevated intraocular pressure. The condition can be less clear when someone has the characteristic anatomic findings of aqueous misdirection but has normal levels of intraocular pressure.”

A shallow anterior chamber with a normal or low intraocular pressure may suggest choroidal effusion or a leak from a surgical site, says Dr. Kolomeyer. A shallow anterior chamber with elevated pressures might be a suprachoroidal hemorrhage. “You can rule out these other diagnoses by fundus exam or B-scan,” she says.

|

Medical Therapy

Typically, you immediately initiate treatment with medical therapy, says Dr. Gedde. There are several options for medical management of aqueous misdirection. Many are used concomitantly, as using only one class of therapy is often less effective than using them in combination.2

• Aqueous suppressants like beta blockers, alpha agonists and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, are used to decrease intraocular pressure and suppress aqueous humor production. They also decrease the amount of fluid misdirected posteriorly. “Typically, atropine is given to try to dilate the pupil and shift the lens-iris diaphragm more posteriorly,” Dr. Gedde adds.

• Osmotics shrink the vitreous cavity, decreasing the volume posteriorly.

• Steroid medications might be used because you have a shallow anterior chamber; you want to minimize the risk of peripheral anterior synechiae formation in that setting.

• Cycloplegics work by inhibiting the ciliary muscle contractions and causing tightening of the zonules, which moves the lens posteriorly, explains Dr. Kolomeyer. “This should break ciliovitreal adhesions and decrease the amount of posterior flow,” she says.

• Mydriatics work by increasing the free surface area of the anterior hyaloid and by further promoting anterior direction of fluid.

• Vitreous dehydrators like mannitol and glycerol will allow the aqueous humor to percolate through the vitreous once again.

Dr. Kolomeyer cautions against stopping medication suddenly if you see resolution. “I taper off the medications,” she says. “The last thing I would stop would be the cycloplegic agent atropine. In some cases, especially if they’re recurrent, the patient might need to be on cycloplegics like atropine long-term.” Dr. Kolomeyer points out that medications work in about half of cases,4 but if the aqueous misdirection isn’t resolved within three to five days, if it recurs, or if there’s significant corneal decompensation related to cornea-lens touch, then laser or surgical intervention should be strongly considered.

Laser

Dr. Gedde says whether laser treatment can be done depends on how much corneal edema is present. “If laser treatment can be performed, I’ll usually proceed with it,” he says. “It’s important to do that first in a pseudophakic eye. And if you’re disrupting the anterior hyaloid, it’s important to do that peripheral to the intraocular lens implant.”

Furthermore, “where the laser is delivered may depend on the degree of pupillary dilation—it may be in the pupil but peripheral to the optic of the lens, if that can be visualized,” continues Dr. Gedde. “Otherwise, it might be done through an iridectomy if an iridectomy is present.”

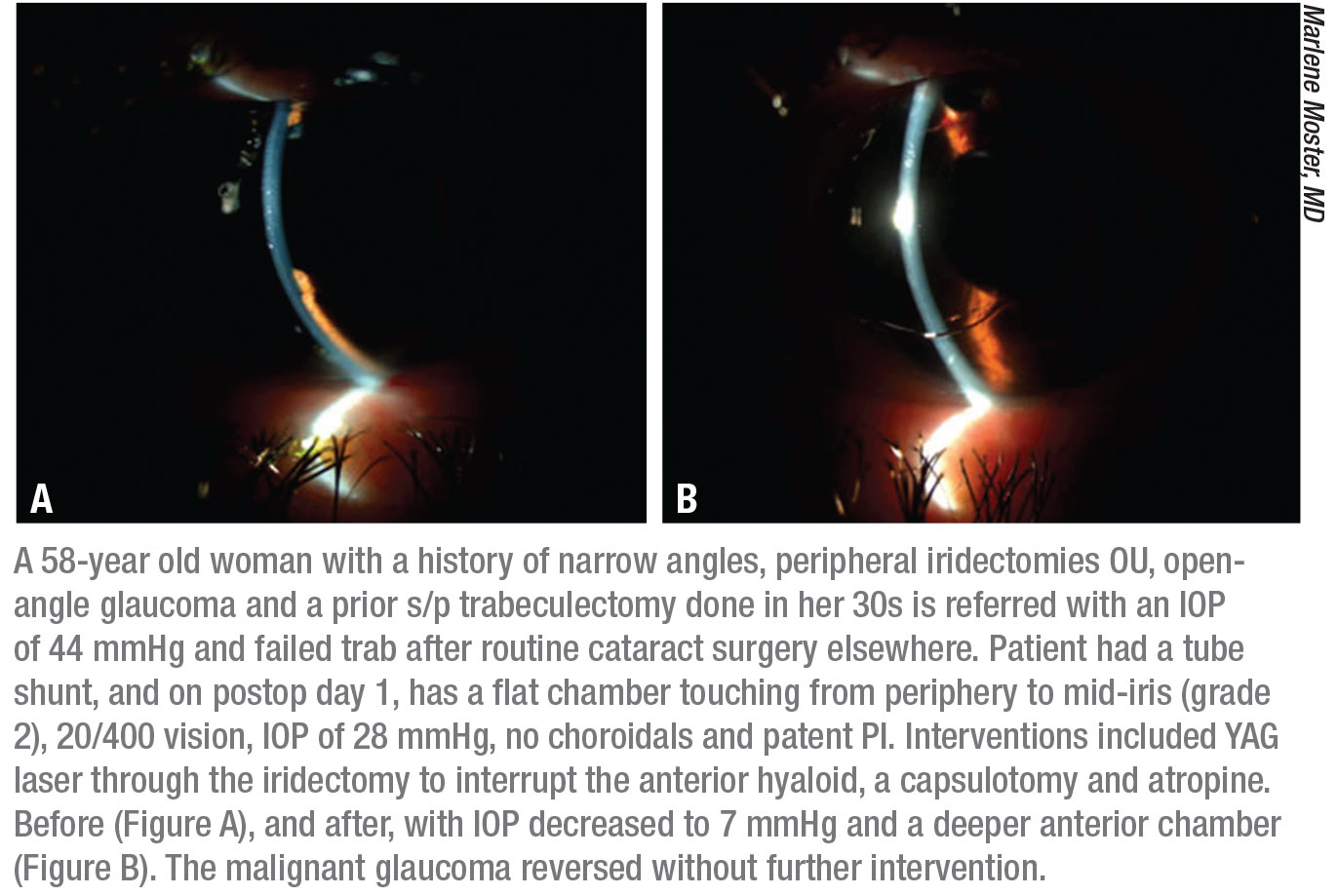

Dr. Moster says you can always laser through the iridectomy in a pseudophakic patient to disrupt the anterior hyaloid face, but this may not be enough. “We routinely do a YAG capsulotomy to break the vitreous face so that aqueous can percolate around the intraocular lens into the anterior chamber. For a phakic patient, we try to laser in the periphery through the surgical iridectomy if they’ve had a trabeculectomy. We try to break the anterior hyaloid face so the aqueous can come into the anterior chamber and exit through the normal trabecular meshwork pathway.”

“We’re not tip-toeing here,” she emphasizes. “We really want to blow the vitreous and anterior hyaloid face apart so aqueous can start coming through. It happens immediately.”

Another option is to perform diode laser cyclophotocoagulation, although this is done less frequently, says Dr. Kolomeyer. Dr. Gedde adds that heat-shrinking the ciliary processes is another laser treatment that’s been described, but he prefers an anterior hyaloidotomy for aqueous misdirection.

Surgery

Depending on the clinical situation, and what response you get to medical therapy and laser, patients may need surgical intervention such as an anterior vitrectomy with iridectomy, hyaloidzonulectomy or a core vitrectomy. “In my opinion, moving fairly promptly to surgical intervention if medication and laser treatment are not having any beneficial effect is important for optimizing the prognosis for these patients,” Dr. Gedde explains.

For a phakic patient, oftentimes the decision will be made to remove the lens at the time of vitrectomy. “That’s because the vitreoretinal surgeon can’t be as aggressive when removing the anterior hyaloid, which is felt to be the area where the blockage occurs,” says Dr. Gedde. “There was a theory out of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute a number of years ago describing a pars plana vitrectomy treatment for aqueous misdirection. It had a high success rate in pseudophakic and aphakic eyes, but less so in phakic eyes unless the lens was removed at the time of the vitrectomy.”

Dr. Kolomeyer agrees that the lens should usually be removed at the time of the procedure if the patient is phakic. If the patient has a history of significant glaucoma or peripheral anterior synechia, she says she would also consider putting in a pars plana tube shunt at the time of surgery to lower intraocular pressure long-term.

The goal of the procedure is to create a unicameral eye, where aqueous can flow easily from the vitreous cavity and posterior chamber into the anterior chamber, says Dr. Moster. Here are some options you can consider:

• Pars plana vitrectomy. “You’re cleaning out the entire anterior hyaloid face so that the blockage no longer remains,” Dr. Moster says. She also suggests doing a lensectomy and capsulotomy with vitrectomy at the same time for phakic patients.

Dr. Gedde adds that you want to create a communication pathway between the vitreous cavity and the anterior chamber. “Typically that’s done by passing a vitrector through the anterior hyaloid, peripheral zonules and peripheral iris,” he says. “That’s a critical maneuver to treat the disease.”

• Clear corneal incision. Dr. Moster says you can use the vitrector to go through the previously-placed iridectomy (or create one in a pseudophakic patient), go through the zonules and through the anterior hyaloid into the vitreous cavity. “You see deepening of the chamber immediately,” she says. “The lens-iris diaphragm moves back into its normal position, the angle opens and the pressure comes down.”

Take care in the postoperative phase. “After any surgery, I would put the patients on cycloplegic agents and anti-inflammatory medications, such as a steroid, watch their IOP and accordingly use IOP medications as well,” Dr. Kolomeyer says.

Outlook

“Aqueous misdirection can’t be fully resolved,” says Dr. Gedde. “Unfortunately, it’s one of those conditions where you may have achieved a resolution, but the condition can recur. Generally though, a restoration of normal anterior chamber anatomy is a good indicator that you’ve sufficiently resolved the misdirection.”

Dr. Moster adds that deepening of the anterior chamber, normal intraocular pressure, an open angle on gonioscopy, lack of pain in the eye and visual acuity returning to baseline are all good indicators that the aqueous misdirection is resolved.

Experts say it’s important to be vigilant—especially for high-risk eyes like those with chronic angle-closure glaucoma, or if aqueous misdirection has already developed in the fellow eye. “Make the diagnosis at the earliest possible juncture and treat promptly for a resolution that will optimize the visual prognosis,” says Dr. Gedde.

Early identification of patients who may be at risk for developing aqueous misdirection may allow you to take some prophylactic measures or make intraoperative modifications, Dr. Kolomeyer adds. These might include performing a peripheral iridotomy prophylactically, depending on the patient’s angle appearance, or placing them on cycloplegics after glaucoma or other intraocular surgeries. “Additionally, you may consider disrupting the anterior hyaloid or performing a vitrectomy at the same time as the planned procedure,” she says.

“This is a multidisciplinary problem and requires a multidisciplinary approach,” Dr. Kolomeyer continues. “Be honest with your patients about what to expect. It often goes beyond an acute episode; patients may have long-standing high intraocular pressure or cataract formation or require multiple procedures. You’ll likely have involvement of the primary ophthalmologist as well as a glaucoma and retina specialist.

“I’m optimistic that further studies on this topic and improvements in imaging technology will help us learn more about aqueous misdirection and improve our treatment approaches,” Dr. Kolomeyer says. REVIEW

1. Kris-Jachym K, Zarnowski T, Rekas Marek. Risk factors of malignant glaucoma occurrence after glaucoma surgery. J Ophthalmol 2017 August 24;2017. Article ID 9616738. [Epub]

2. Chandler PA, Simmons RJ, Grant WM. Malignant glaucoma: Medical and surgical treatment. Am J Ophthalmol 1968;66:3:495-502.

3. Debrouwere V, et al. Outcomes of different management options for malignant glaucoma: A retrospective study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2012;250:1:131-41.

4. Simmons RJ. Malignant glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1972;56:3:263-72.