Most cataract surgeons say consistency is their top goal when creating a capsulorhexis. Then, with furrowed brow, they may explain the inevitable need to adopt variations to ensure reproducible and stable longterm results in this era of premium refractive IOLs.

Sound familiar? Here, surgeons offer insights you can use to establish a baseline approach and respond on short notice when circumstances in the OR dictate a need to do so.

Taking Control

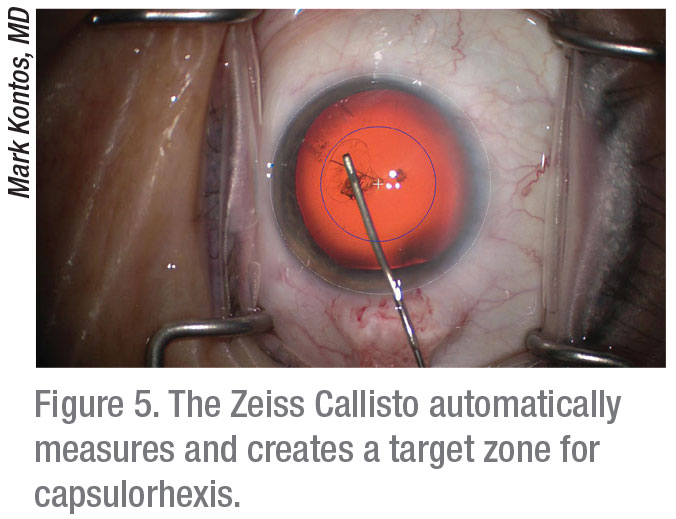

Mark Kontos, MD, a senior partner at Empire Eye Physicians, which has offices in eastern Washington and northern Idaho, says he uses a cystotome to maximize the chances of making a perfectly centered capsulorhexis.

|

“I like to use the cystotome because it gives me more control,” he says. “When I’m creating the capsulorhexis, I don’t rush. I look at the visual axis of the patient to get an idea of the size I’m trying to achieve. I maintain control of the edge and maintain good visibility. I can keep the casulorhexis exactly the size I want it to be, usually a standard of 4.8 to 5 mm.”

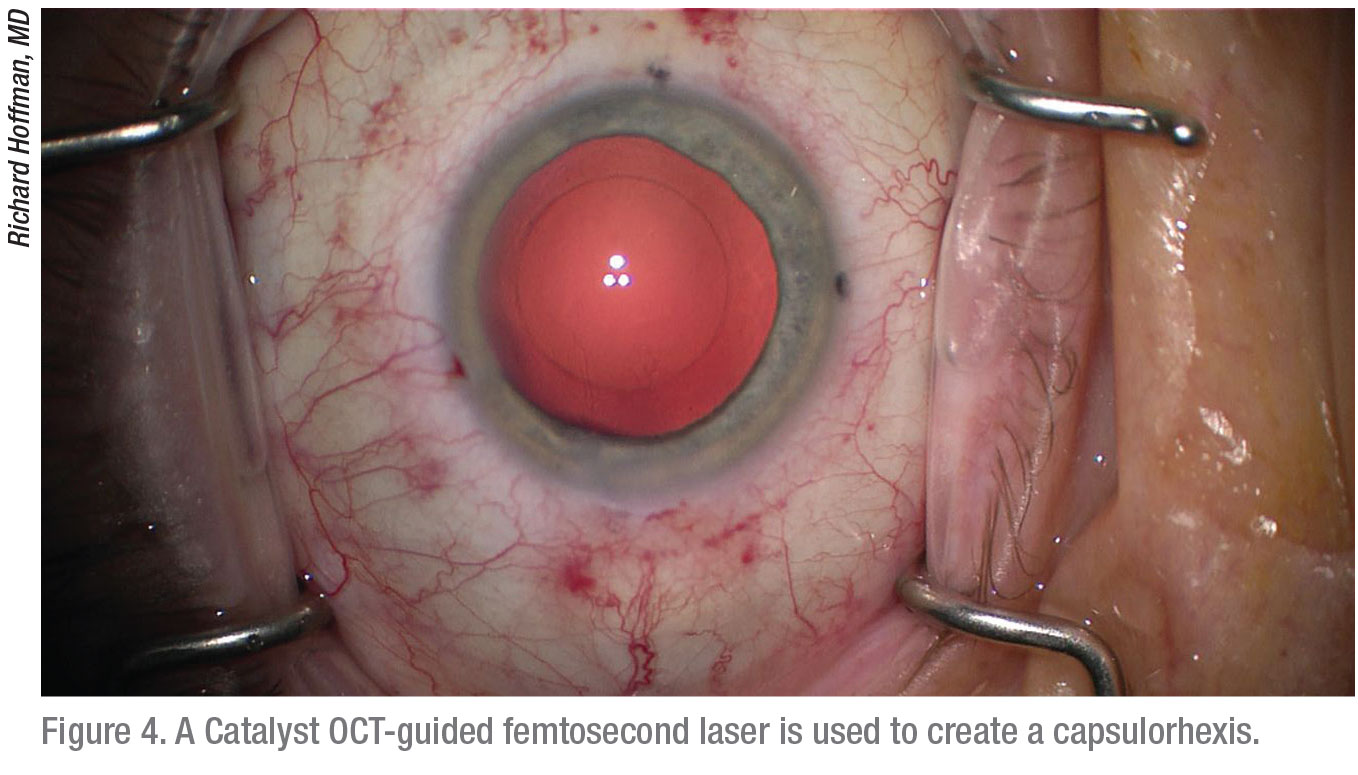

For patients willing to pay extra as part of their refractive package, Dr. Kontos offers to do their capsulorhexis with the Catalys femtosecond laser. “The laser is best at ensuring absolute uniformity, helping me create a well-centered capsulorhexis,” he says. “It puts me at the leading edge. I set parameters, and an OCT unit built into the laser measures the capsulorhexis. By default, based on the way the laser does the procedure, I’m centered over the capsular bag.”

In some cases, when a patient has a high angle kappa, for example, he adjusts the laser to slightly decenter the capsulorhexis. “The thing that’s nice about the laser is that you can do a capsulorhexis in less than a second,” says Dr. Kontos. “So, you don’t have to worry about a lot of variability. When you have complete control of the whole process, it allows you to do just about anything you want in terms of sizing and location.”

Avoiding Risks

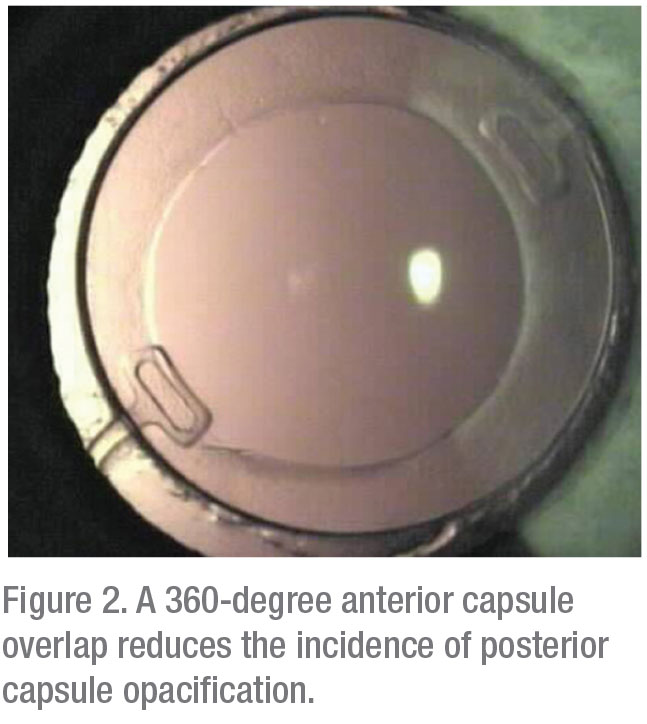

Uday Devgan, MD, FACS, FRCS, a partner at Specialty Surgical Center, Beverly Hills, California, cautions against making a capsulorhexis that’s too small—in most cases. “For an optic size of 6 mm in diameter, we want a capsulorhexis that’s 5 to 5.5 mm in diameter so that it overlaps for a full 360 degrees,” says Dr. Devgan, also chief of ophthalmology at Olive View UCLA Medical Center. “Making a smaller capsulorhexis will only make the nucleus removal more challenging and will result in a smaller effective optic size when the anterior capsular rim opacifies with time.”

Dr. Kontos adds that a capsulorhexis made too small is destined for unwanted contraction. “In capsular contraction syndrome, the capsule might start at 4 mm and contract down to 3 mm or 2 mm over time,” he says. “This can result in fibrosis, putting a lot of strain on the zonules and causing dehiscence. The lens could end up shifting and becoming dislocated after you finish the surgery. This can potentially impair vision and create the need for an anterior YAG laser procedure for you to resolve postop symptoms.”

Large capsulorhexis size isn’t an absolute protection against risk, however. Dr. Devgan notes that you need to know when a small capsulorhexis is actually indicated. “You want a smaller capsulorhexis when another surgery—such as DMEK, a glaucoma tube shunt procedure or a pars plana vitrectomy—is performed concomitantly,” he says. “We want to prevent the optic from escaping from the capsular bag during these combined procedures.”

|

Although you typically want to make the capsulorhexis overlap the lens optic by about 0.5 mm all the way around the optic, Richard Hoffman, MD, who practices in Eugene, Oregon, says you may discover a need to slightly increase or decrease the overlap in some cases. “The risk of making your capsulorhexis too large is that you’ll have a greater chance of seeing your rhexis move out to the equator and then losing it,” says Dr. Hoffman. “The risk of making it too small—which is easy to do—can become more clear when you do the hydrodissection steps. You may find that the fluid has a difficult time getting around a dense lens, and you can actually blow out the posterior capsule.”

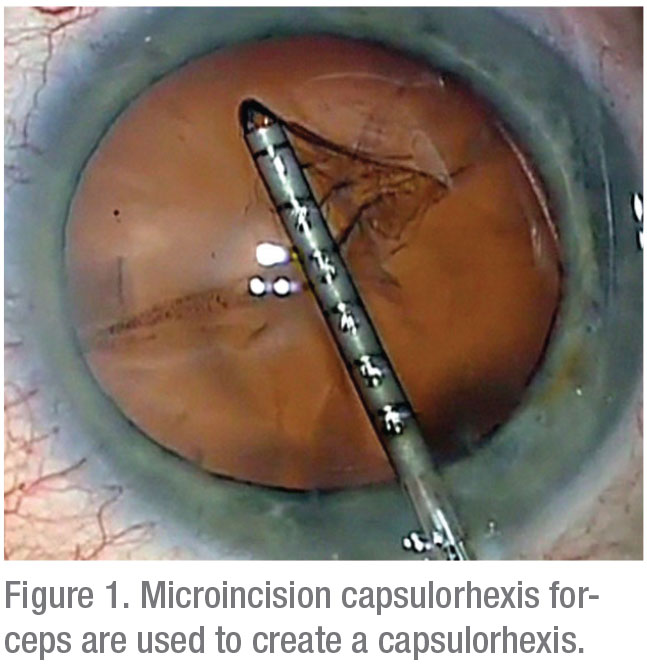

When doing a routine capsulorhexis, Dr. Hoffman says he makes sure he puts enough viscoelastic into the patient’s eye to keep the lens from from prolapsing forward. “I also use a microincision capsulorhexis forceps to help create the capsulorhexis,” he adds. “It has millimeter marks on the cannula so that when I put it in the eye, I can hold it over the anterior capsule and visualize what a 5-mm size would be.

“When I do the capsulorhexis, I usually start in the center and perforate the lens,” he says. “I’ll cut out about 2 to 3 mm with the blade of the forceps. Then I’ll just grab that flap and rotate it around. Most surgeons do their capsulorhexis through the coaxial wound, which is about 2.2 to 2.5 mm. That works fine in normal eyes.” In a high-risk eye, he adds, he starts with a smaller opening and spirals out to the size that he wants.

Avoiding Intraocular Issues

|

Dr. Kontos warns that a capsulorhexis can get so over-sized that it risks creating an intraocular issue. “A large capsulorhexis can get into the zonules,” he says. “It’s hard to tell at times how much the zonules have moved to the center of the capsule. You can’t always see them. Sometimes, when you’re making a large capsulorhexis and you get into where the zonules are attached, inside the capsular structure, it’s very easy for the capsulorhexis to radialize and no longer function as a continuous, circular capsulorhexis.”

Another potential issue: If the capsular edge doesn’t overlap the edge of the lens, this means the rhexis is too large, he points out.

“It can lead to instability of the lens inside the bag,” he says. “Sometimes, as the capsule contracts, if a portion of the lens is not overlapped by the circumference of the capsule, then that part of the lens can pop out of the capsule, and the capsule can contract behind it. That can lead to malposition of the lens inside the bag, and sometimes those forces can move the lens in any given direction. That, in turn, could lead to a refractive shift or astigmatism.”

If these or other issues arise while you’re still in the patient’s eye, Dr. Kontos urges you to take a calm problem-solving approach as you continue your procedure. “For example, if you feel like the capsulorhexis is extending beyond where you want it to be, add viscoelastic and direct the capsule in the direction that you want—and the size that you want it to be,” he says.

“If you realize you’ve made your capsulorhexis too small, or you think you’re making it too small, just continue what you’re doing and complete the capsulorhexis,” Dr. Kontos adds. “Then you can go back and make a bigger capsulorhexis around the one that’s too small, instead of trying to make the original capsulorhexis bigger at the end of your first attempt, potentially creating an irregularly shaped capsulorhexis.”

Pseudoexfoliation Challenge

Pseudoexfoliation syndrome poses a familiar and unique challenge when making a capsulorhexis. “I recommend making a sufficiently large capsulorhexis of at least 5 mm in diameter for these patients, since they tend to get capsular phimosis,” says Dr. Devgan. Bringing the cataract partially out of the capsular bag can help minimize stress on the zonules while you disassemble the nucleus, he adds.

Dr. Hoffman says he’s comfortable creating a capsulorhexis of 7 mm for his pseudoexfoliation-syndrome patients, especially when a dense, rock-hard cataract is involved. “I think it’s safer to do the case through a capsulorhexis of this size,” he notes. For posterior polar cataracts, when the patient’s capsule is at high risk of rupturing, Dr. Hoffman says he tries to make the capsulorhexis about 5 mm. “That way, if the posterior capsule ruptures, you have the option of putting a three-piece lens in the ciliary sulcus and the optic cap, capturing the optic through the anterior capsulorhexis to stabilize the lens,” he points out.

|

Impact on IOL Calculations

Surgeons recommend that you carefully consider the impact of your capsulorhexis on your IOL calculations.

“Remember these calculations are based on a best estimate of where the lens sits inside the bag, the effective lens position” says Dr. Kontos. “A number of factors affect this. The impact of the capsulorhexis won’t be the same if it’s a different size every time.”

|

Evidence suggests that the effective lens position is altered by these variations, he continues. “If you’re going to use an A-constant to personalize your lens calculations, then you have to insist on a capsulorhexis that’s uniform every time. If not, you really can’t have a reliable A-constant that’s personalized for what you’re trying to accomplish.”

Dr. Devgan notes that a lens calculation depends on three simple factors. “You have the keratometry, the axial length of the eye and the exact location in the eye where the IOL will sit,” he says. “Where will it sit? Will it be it 3 mm back? Or 3.2 mm, 3.5 mm or 4 mm back? Shifting the lens even a fraction of a millimeter will change the refractive outcome a lot. All of the formulas have different ways of trying to figure out the effective lens position.

“If you have a rhexis that’s not going to hold the lens securely, then there’s no way of really determining where the lens will sit in the eye,” he concludes. “So I’m going to make a consistent rhexis in every case. My rhexis going to overlap the optic. It’s going to hold it securely in place. Then I’ll have a lot more accuracy in determining the effective lens position, and therefore a more accurate calculation.”

Your Signature

Dr. Devgan encourages his colleagues to look at each capsulorhexis as a part of their legacy.

“The capsulorhexis is an important part of your signature that you leave in every eye,” he says. “Even decades after your surgery, a fellow doctor will be able to examine that eye and see the results of your handiwork. A centered and precise capsulorhexis will securely hold the IOL optic in position for the most accurate refractive outcome over time.” REVIEW

Dr. Kontos is a consultant for Zeiss, Sun, Allergan and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Devgan is the owner of Catataractcoach.com, a free online education site. He’s served as a consultant and speaker for Alcon and Bausch + Lomb, and he’s a principal for LensGen and IOLCalc.com. Dr. Hoffman is a consultant for MicroSurgical Technology.