Risk Prevention

Surgeons say you can avoid having to deal with ingrowth if you watch for certain predisposing factors ahead of time.

“Epithelial ingrowth can happen early or late after the surgery,” says Boston surgeon Samir Melki. “Of course, the further away from the procedure you are, the less of a chance of developing an ingrowth after an initial procedure. You also have a higher chance of developing an ingrowth after an enhancement, and some surgeons avoid LASIK enhancements more than two years after the original procedure because they feel the risk of ingrowth is higher after enhancements that are performed further out.” Other risk factors Dr. Melki lists are:

• age; the older a patient is the more friable the epithelium and the higher the risk of an ingrowth;

• an epithelial defect during surgery from intraoperative trauma;

• epithelial basement membrane dystrophy that makes the epithelium loose and is only recognized during surgery;

• epithelial tags on the edge of the flap that are on the stroma rather than pushed outside the stromal bed by the surgeon; and

• the presence of a buttonhole flap, which can allow cells to grow through the hole in the center of the cornea.

Taking Action vs. Waiting

Taking Action vs. Waiting

Some surgeons take different approaches to ingrowth, depending on its extent, its effects and its location. Some prefer to jump on ingrowth immediately, while others will observe it if it’s not an immediate threat.

Asim Piracha, MD, of Louisville, Ky., likes to eliminate any ingrowth he finds. “If epithelial ingrowth is present early postop, such as on day one or during the first week, I’ll treat it whether it’s causing problems or not, rather than wait to treat it later,” he says. This includes little nests of epithelium that result from little pieces of epithelium being left behind under the flap. “If that’s the case, I’ll remove it right away to avoid issues and have a clear interface,” says Dr. Piracha.

However, Dr. Piracha takes a different tack for epithelial ingrowth that appears late. “If it’s months or years after surgery, then you have to follow the ingrowth’s course,” he says. “Generally, if it’s less than 2 mm from its origin, there’s no overlying epithelial staining and the rest of the flap epithelium is smooth with no staining, I’ll observe it. But if it’s inducing refractive changes, such as a hyperopic shift or astigmatism, or there are overlying epithelial issues, staining or defects, or if it’s progressive, I’ll remove it.”

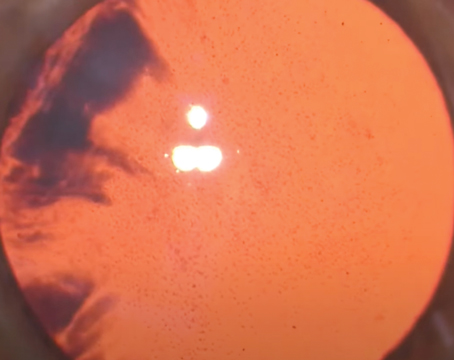

Dr. Melki doesn’t necessarily go after all ingrowth. “Just because you have an ingrowth doesn’t mean you have to do something about it,” he says. “I’ll just watch it in the beginning. One way to decide the interval at which to follow the ingrowth is to instill fluorescein on the cornea. When you do this, you may see some staining on the edge of the flap, and that will give you an idea where the fistula is and whether it’s closed yet. As long as that interface is open, you have to be vigilant. For cases of cells that may have been implanted during the LASIK surgery, but don’t have a connection to the outside of the flap, I’m not as concerned.

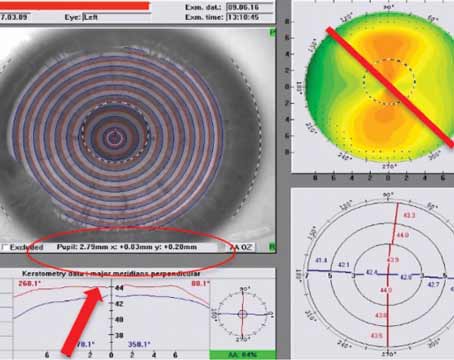

“Also, when you look at the ingrowth, what you see at the slit lamp isn’t necessarily all that is there,” adds Dr. Melki. “The leading edge of the ingrowth is usually farther than the edge that you can see, composed of microscopic cells. So, always assume there’s more than what you see.” He says another way to follow epithelial ingrowth is serial topography, which will show the presence of melting.

Removing the Cells

When surgeons decide it’s time to remove ingrowth, they say they’ll start with the least invasive approaches first.

Though Dr. Piracha says the cases of epithelial ingrowth he sees are almost always recalcitrant cases that he gets by referral, he does have a progression of techniques he would go through should an initial case present itself. “If you see a small nest of epithelium with a little fistula on the edge, and you’re afraid it will get worse, I think the YAG treatment described by Jorge Alio has had some limited success in disrupting the ingrowth in such cases,” he says. “It can break the source of the epithelium without having to lift the flap.” Dr. Piracha explains that, in the YAG treatment, the surgeon focuses the laser on the epithelium with the defocus of the laser set at zero and begins with a power of 2 mJ. He then begins stepping up the power until the epithelial cells are disrupted and the area of the fistula has been treated. The loose epithelial cells will be resorbed, Dr. Piracha says. It may take a couple of treatments to get all the ingrowth, however.

Another minimally invasive way some surgeons remove cells involves just barely lifting the flap. Chicago surgeon Mitch Jackson explains it in more detail: “A technique I use involves filling a syringe with BSS and putting it on a 21-ga. Slade cannula [Accutome],” he explains.

“Then, at the slit lamp, I insert the cannula under the edge of the flap right where the ingrowth is entering and irrigate it out. This actually blows the epithelium right out through the same small opening that the cannula is in; it comes out like a sheet. The advantage to this is you’ve only created a small opening rather than lifted the entire edge of the flap, decreasing the chance of a recurrence from new cells getting under the flap. And, if the ingrowth comes back at all it’s just as a little trickle of cells near the edge. Afterward I’ll place a bandage contact lens for comfort, though it’s not mandatory. I prescribe an antibiotic drop and an anti-inflammatory for up to seven days depending on how the eye looks.” Dr. Jackson says he uses the same technique for cells that are even more centrally located.

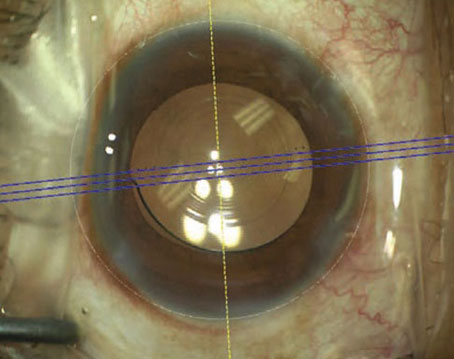

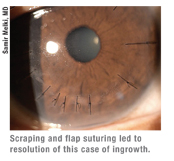

For recurrent ingrowth or in cases surgeons feel warrant lifting the flap completely, many surgeons will lift the flap and scrape both the bed and the underside of the flap. “I recommend making sure the flap is sitting on a hard surface when you scrape it,” advises Dr. Melki. “If it’s on conjunctiva it will be loose and flopping all around. I recommend using a platform or a closed lid speculum and resting the flap on that.” To aid with this, Dr. Melki designed the Melki Flap Stabilizer (Rhein Medical), which has a vacuum to keep the flap sucked down and immobile as it’s scraped. For scraping, Dr. Melki uses a dry fiber cellulose sponge or a spatula suitable for scraping. For certain recurrent cases, Dr. Piracha will seal the flap down with Tisseel glue after scraping. He’ll cover the eye with a contact lens and then, after about a week, the cornea will re-epithelialize and the lens can be removed.

For the truly tough cases that are referred to Dr. Piracha, after scraping he’ll remove a little of the peripheral epithelium, as well as some outside the flap region. He then sutures the flap following the protocol proposed by Chicago surgeon Parag Majmudar. “To mark the suture locations I use an eight-bladed RK marker centered on the flap,” Dr. Piracha explains. “One prong of the marker will be over the hinge. I then put in seven radial 10-0 nylon sutures perpendicular to the margin, avoiding the hinge area. The sutures are full-thickness through the flap and about 33 to 50 percent of the stroma. If there’s an area of peripheral flap melt, I may place an additional suture or two in the area of the melt to reapproximate the wound and make sure there’s no gap for renewed epithelial ingrowth. I bury the knot in stroma peripheral to the flap, increasing the amount of tension until I notice striae and confirm that the gap at the edge of the margin is closed.” Dr. Piracha places a contact lens and leaves it on for one to seven days depending on how long it takes for the defect to heal. He’ll leave the sutures in the cornea for longer than two weeks, and will start taking them out at four to six weeks. “I usually remove three sutures at the first visit and then the remaining four six to eight weeks later. I may take them out a little later than most surgeons, but I haven’t yet had to go back for more ingrowth with this approach. Maybe there’s a little voodoo involved in that my technique works and I don’t want to mess with it.”