How many times have you heard a 20/20 postop cataract patient say his vision is disappointing? Or a 20/40 who tells you she can see perfectly? If you can remember such a case, or can think of similar ones, you’re not alone. Increasingly, cataract surgeons report that one of their biggest challenges today is ensuring that the quality of patients’ postop vision is as good or better than their acuity.

Sometimes that means hitting 20/20 Snellen, sometimes not.

Part of the challenge is matching patients’ varied visual needs with the individualized solutions made possible by a growing assortment of advanced intraocular lenses. Another part of the challenge is the need to respond to the once-overlooked nuances on the cornea and inside the eye that are now recognizable because of the growing sophistication of today’s diagnostic technologies. Finally, the availability of increased ocular surface treatments ups the ante in many of these cases. Here, surgeons explain how they avoid patient unhappiness and maximize positive outcomes by following new approaches preoperatively, intraoperatively and postoperatively.

Why Now?

Y. Ralph Chu, MD, Founder, CEO and Medical Director of Chu Vision Institute and Chu Surgery Center in Bloomington, Minnesota, puts the issue of vision quality into simple terms: “We’ve learned over the past 20 years that Snellen acuity doesn’t define the quality of a patient’s vision,” he says. “For example, in many situations, including clinical trials, we’ve seen loss of contrast sensitivity compromise aspects of functional living, such as the ability to drive at night for patients who have shown acceptable results on the Snellen chart. Some patients can actually have very good visual acuity, even in the presence of dim lighting conditions. But as soon as a source of glare hits their eyes, the quality of their vision decreases dramatically.”

Dr. Chu says wavefront aberrometery and other diagnostics available today enable you to evaluate a patient’s entire optical system, including the cornea and ocular structures, for potential sources of suboptimal vision. “We shouldn’t focus on just the pathology—a cataract in this case,” he says. “Remember that something as simple as an epiretinal membrane can also affect the patient’s vision.”

Bryan Lee, MD, JD, who’s in private practice at Altos Eye Physicians in Los Altos, California, agrees with this notion, saying the clinical measures used for clinical trials and related purposes are difficult to quantify. “We all see patients whose vision doesn’t necessarily reflect a measurement on the Snellen chart,” says Dr. Lee, who is also an adjunct clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University. “When it comes to defining success, I think we still have to figure out better measures as a profession. Right now, it’s highly subjective. A lot depends on what the patient tells you, which is fair because the need for cataract surgery should be based on visual functioning and the patient’s quality of life.”

At the same time, Dr. Lee continues, “when I’m determining how patients are doing postop—despite what I’ve just said—I have to admit that I’d prefer my evaluation to also be based on at least some objective measures that I can consider. We have to know what the patient sees. In our practice, we try to get at that by doing a lot of testing, such as reducing contrast on the Snellen chart by 50 percent.”

Yuri McKee, MD, MS, a corneal and refractive surgeon at East Valley Ophthalmology in Mesa, Arizona, says the key measure of success he seeks to achieve when striving to optimize vision is, quite simply, patient happiness. “I want to know if they feel they’ve met their goals.” he asks. “I want to know if they would recommend a friend or family member to see me for surgery. Measured visual acuity is important, but happy patients are the best indicator of success.”

Dr. McKee says his practice spends a lot time on patient surveys to profile happy and unhappy patients. “We take all reviews, good and bad, very seriously,” he says. “Sometimes, patients complain about things I can’t change, like an epiretinal membrane, but even this reminds me to spend more time counseling patients about pre-existing pathology. Sometimes patients give us great feedback that reflects well on our practice processes and staff. If a patient has a negative comment, we scrutinize the related process to see how we can improve the patient experience.”

First Things First

Asking patients a lot of incisive preop questions remains one of the most effective methods of determining your potential for maximizing their vision quality, according to Brian Shafer, MD, a cornea, refractive, glaucoma and anterior segment fellow at Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. For example, how do patients feel when they’re driving? Can they read all of the signs in front of them? How about when they’re driving at night? Can they read the stop signs or the license plate on the car in front of them? How much glare do they see when a car is approaching them from another direction? Is it significant enough to make them avert their eyes?

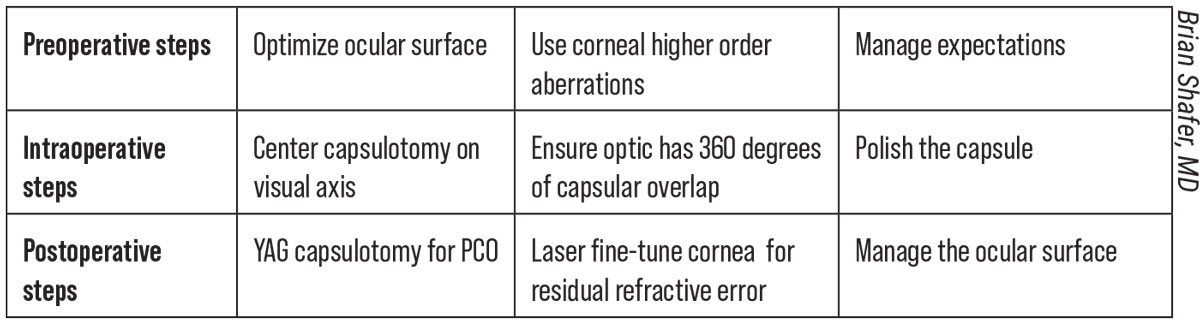

|

|

Suggestions on how to optimize vision with cataract surgery. Click image to enlarge. |

“Taking this approach moves us to the forefront of the refractive surgery mindset,” says Dr. Shafer. “For a number of years, as my mentors and colleagues are quick to point out, patients measuring 20/20 after refractive procedures have still been troubled by glare and other issues, such as problems driving at night. Now, these issues are surfacing in the IOL space. We’re learning a lot more about how to maximize vision quality in what has evolved into what we call refractive-cataract surgery.”

Dr. Lee likes to remind colleagues that patients’ visual needs vary more than was fully appreciated in the past. For example, patients may spend most of their time reading from desktop computers, laptops, tablets, cell phones and printed text—or combinations of these formats.

“Patients may also be reading at different distances that we need to identify,” he points out. “There’s no ideal number for us to hit when measuring the vision a patient has while reading. But we pay close attention to the quality, speed and ease of how the patient reads. We’re constantly striving to measure quantitative and qualitative aspects of their vision.”

Ultimately, he admits, achieving optimal vision—or going beyond the clinical definition of perfect—is a “huge” challenge when caring for some patients.

“The outcomes of cataract surgery are very good these days,” he notes. “If patients are healthy, their acuity is going to be really high. As far as assessing their happiness, that’s really hard because patient satisfaction varies so much. One person’s definition of success applies to only that one person. I don’t think we’ll ever have a perfect system that will tell us exactly what we want to know.”

Beyond the use of questionnaires—always critical before surgery—Dr. Lee uses extensive preop conversations with patients to shed light on their goals and personalities, which are also critical to know. “For example, a patient might say, ‘I’m here because I can’t see my golf ball,’” he says. “Obviously, the goal will be to help the patient achieve good outdoor distance vision, slightly different than good indoor distance vision. These conversations are an ongoing challenge because there are so many lens options to choose from. We need to talk through the pros and cons and help narrow the choices for them.”

Premium Considerations

Kathryn M. Hatch, MD, director of the refractive surgery service at Massachusetts Eye & Ear and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, assesses a patient’s suitability for premium IOLs by first focusing on preop symptoms not related to her patient’s mature cataracts.

“Patients may have starbursts because of pupil size, for example,” she says. “Or their preoperative symptoms could just be related to their anatomy. If they have these symptoms before surgery, you have to keep in mind that they’ll likely still have these symptoms after surgery.”

She relies on wavefront aberrometry to identify pre-existing issues, such as higher-order aberrations or alpha and kappa angles that suggest the pupil isn’t the center of the visual axis. “If you see a very large angle, you may want to avoid a multifocal because it could mean the patient won’t be happy looking through the center of the IOL, especially if it’s an IOL with a diffractive optic,” she says.

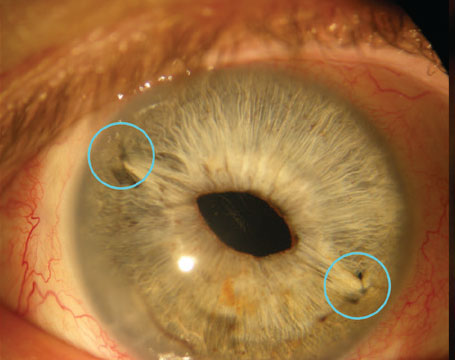

|

|

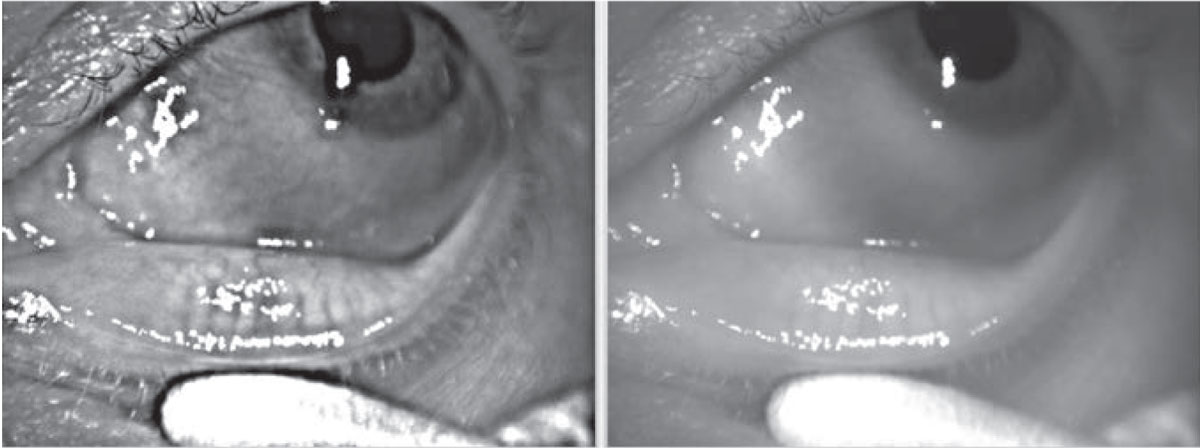

This patient was experiencing persistent and intolerable negative dysphotopsias after cataract surgery (left). A reverse optic capture eliminated the troublesome symptoms (right). |

Dr. Shafer focuses preoperatively on “corneal-only” higher-level aberrations, quantifying how much light is being scattered by the corneal shape. These effects are distinctly different from internal higher-order aberrations associated with the dysfunctional lens that he’s preparing to remove.

“Although I don’t follow any hard and fast rules on this, I generally consider corneal higher order aberrations greater than 0.3 RMS a risk factor for decreased postop visual quality,” he says. “For these patients, I tend to avoid implanting a diffractive multifocal lens, which will split light in bothersome ways for any patient who already has the propensity for developing positive dysphotopsias, such as glare and halos. I find this approach can lead to improved outcomes and optimized vision quality.”

When patients are considering premium lenses in her practice, Dr. Hatch pays close attention to how they react when she tells them that they may experience postop halos and glare.

“If they have a strong reaction to that possibility, I know that these lenses might not be a good idea for them,” she notes. “In some ways, I’m letting patients weed themselves out. A patient might say, ‘Oh, I’m fine wearing reading glasses.’ Then I’ll get the patient who says, ‘I’ll do anything I can to get out of my glasses!’ Being ready to do anything, of course, must include a willingness to pay the extra cost of a premium IOL that’s not covered by insurance. At that point, I start looking at what lens might be best for that type of patient.”

Dr. Lee also relies heavily on high-order aberrometry to screen for risks of positive dysphotopsias, most importantly if patients choose multifocal, extended depth-of-focus or trifocal lenses.

“We try to avoid premium lenses when we think hitting plano will be very difficult,” he says. “We’re also factoring in the personality types that we’ve observed or documented to determine if we think we’re going to be able to satisfy the patient.”

For some of these cases, Dr. Lee and his colleagues recommend the use of a monofocal IOL.

“When we implant a monofocal as the first lens or as a replacement for a premium lens in an unhappy patient, we make sure we appropriately manage the patient’s expectations about the need to wear glasses,” he says. “As a result, I don’t usually see many patients with monofocal lenses who are dissatisfied with their vision.”

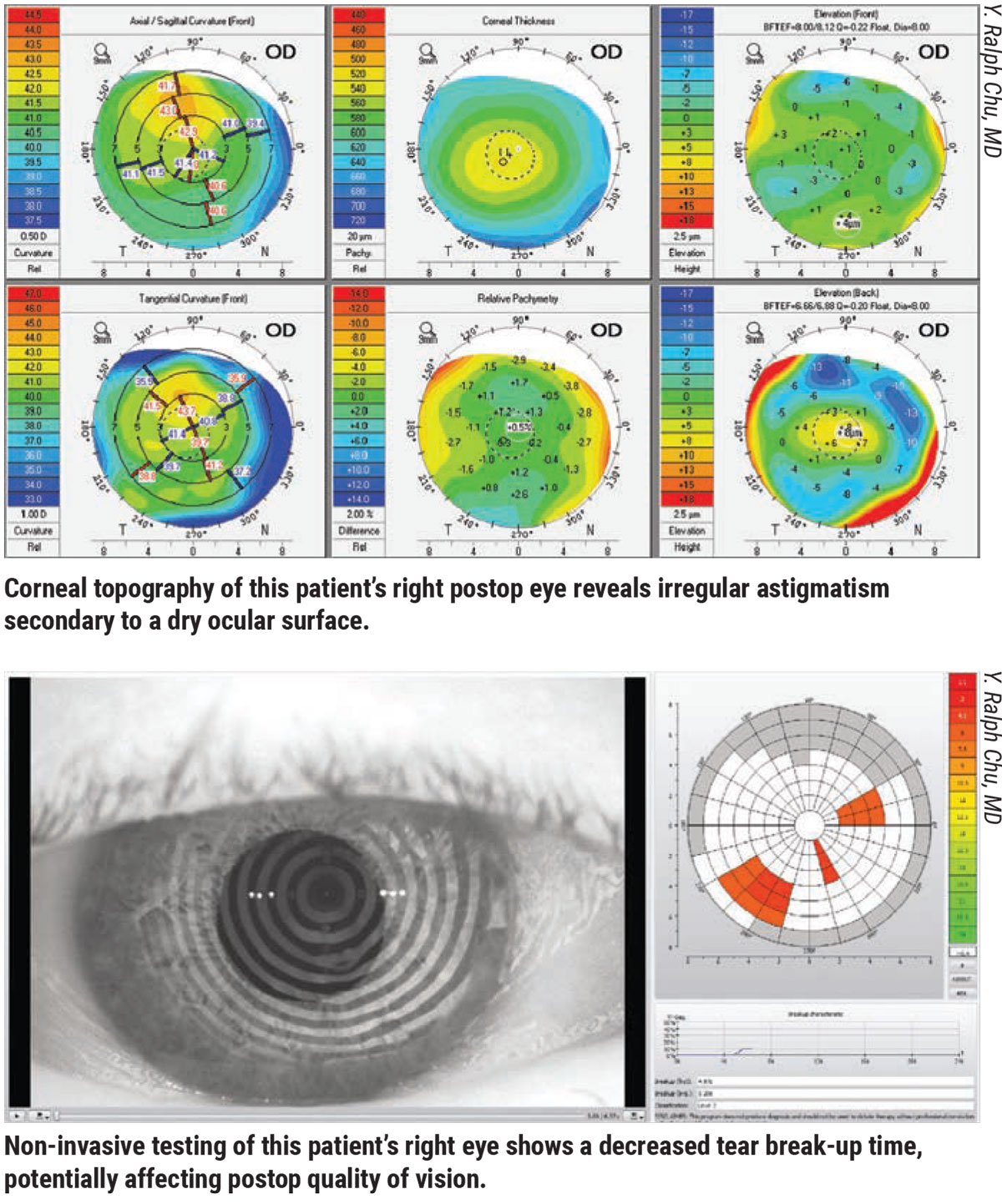

Dr. Chu recommends widening your diagnostic approach. “In many cataract patients, we need to remember that the overall quality of their vision is declining because of the aging of their eyes,’’ he says. “We see cataracts, but their problems could also be due to degradation of the tear film. We have also learned that dry eye or the broader category of ocular surface disease, can be a significant source of poor vision quality.”

Ocular Surface Management

Surgeons say that all efforts should be made to ensure a pristine ocular surface to optimize postop vision, since a disrupted ocular surface can negatively affect visual acuity. “If a patient has an abnormal tear film or epithelial basement membrane dystrophy,” says Dr. Shafer, “that patient may have what we call epithelial blur. The patient’s postop vision may refract to 20/20, but he or she will experience a blur from a disrupted ocular surface.”

For these patients, Dr. Shafer places a gas permeable contact lens over the patient’s eye before surgery, bypassing the epithelium/tear-film interface. A sudden development of crisp vision can confirm that the reduced visual quality is secondary to tear film or epithelial issues, according to Dr. Shafer.

“We then know we need to address the surface of the eye, including the possibilities of aqueous deficiency, requiring us to use punctal plugs to boost the tear film; or meibomian gland dysfunction, calling for treatment of the glands with such devices as Lipiflow, TearCare, or warm compresses for manual expression,” says Dr. Shafer. “If there’s an inflammatory component to the patient’s dry eye, we treat the inflammatory condition. Completing this treatment generally takes six weeks before the patient is ready for surgery.”

|

Dr. Shafer rules out EBMD with what he calls the “loose carpet” test. “The epithelium in these patients is, in fact, like a loose carpet,” he notes. “I rub the epithelium with a cotton swab, and if the epithelium moves, I know it’s sick and has to be removed.” For EBMD, he performs a superficial keratectomy, polishes the corneal surface with a diamond burr and finishes with a gentle phototherapeutic keratectomy, applying excimer laser pulses to the periphery and center of the cornea. He says he typically follows with cataract surgery three months after this procedure.

Intraoperative Techniques

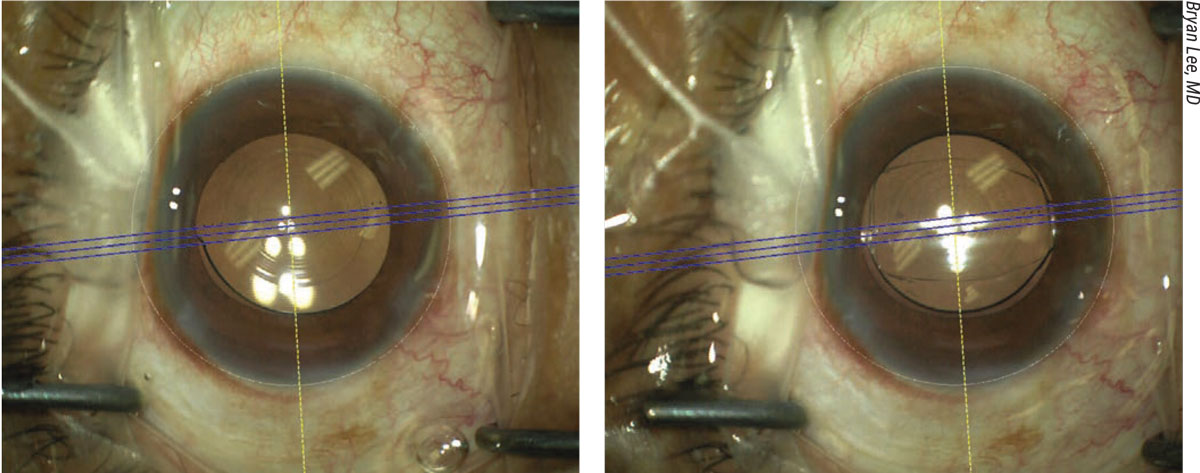

During surgery, Dr. Shafer confirms that the capsulotomy is centered on the visual axis. He then creates a 5.2- or 5.3-mm capsulorhexis to ensure there’s adequate capsular overlap on the optic. “If there’s 360 degrees of overlap of the IOL, that lens will be rock-solid stable,” he says. “If the capsulotomy is centered on the visual axis, the central portion of the optic will be right at the visual axis. That will allow it to function optimally.”

Dr. Shafer also polishes the posterior capsule to minimize the possibility of posterior capsule opacification from developing. “When appropriate, a YAG capsulotomy is also reasonable to do, typically three months postop, to help improve visual quality if there’s any PCO at all,” he says. “But it’s somewhat optional if there’s a lot of cortex on the posterior capsule.”

For premium lens patients, Dr. Shafer says he routinely performs PRK or LASIK as a final “tune-up” to ensure the patient benefits from the best vision possible. “We price our premium offering so that the premium cataract surgery patient pays for this enhancement up front, after we explain how it works,” he explains.

Meanwhile, before performing a YAG capsulotomy, Dr. Hatch recommends making sure the lens itself isn’t the issue affecting vision. “You wouldn’t want to do a YAG and then find out that you have to do a lens replacement, even in a rare situation,” she says.

Dr. Lee also uses the YAG laser after implanting premium IOLs, but only in patients who were initially happy with the lens before glare and halos developed at night. “If a patient isn’t initially happy with the quality of vision the lens provides, it’s a clue that the optics of the lens aren’t working for the patient. I won’t perform a YAG capsulotomy because we may need to do a lens replacement.”

Postop Measures

The biggest challenges typically facing Dr. Lee and his patients are positive dysphotopsias at night, especially when the patients have received premium IOLs.

|

|

Preoperative imaging of the meibomian gland shows truncated glands corresponding to a lipid deficiency in the tear film of this patient. This is just one more condition to consider when identifying and addressing factors that can prevent you from achieving the best possible cataract surgery outcomes. Image courtesy of Y. Ralph Chu, MD. |

“A lot of these patients are functionally doing very well without glasses,” he notes. “I’ll tell them to keep a pair of glasses in the car and put them on when they’re driving at night. Other times, when necessary, we may prescribe brimonidine or even pilocarpine to try to shrink the pupil and reduce some of the nighttime positive dysphotopsias. For extreme cases of positive dysphotopsias, meanwhile, we can usually help a patient by doing a lens exchange. I do a high number of lens exchanges in my practice. Most of these patients do very well.”

Negative dysphotopsias present a different challenge, creating unexpected shadows or dark crescents, almost always in the postop patient’s temporal vision, according to Dr. Lee.

“These manifestations are unpredictable, sometimes occurring in patients who have apparently good outcomes,” he says. “Some patients may even have the same lens in both eyes and have symptoms in one eye but not the other. The good news, however, is that negative dysphotopsias almost always go away with time. If they persist and the patient comes back to me with the same complaints in three months, we can try to do a reverse optic capture, surgically elevating the optic out of the capsule and into the sulcus and leaving the haptics in the bag. Doing this changes the position of the lens edge or the overlap of the capsule and lens edge in most patients, reducing negative dysphotopsias. (See the second figure.) If that doesn’t work, the next step would be to put a replacement lens in the sulcus and suture the lens to the iris.”

To spare postop patients negative dysphotopsias, Dr. McKee tries to avoid the use of square-edged IOLs, which he finds to be more frequently associated with these disturbances.

“A smooth, rounded anterior optic doesn’t seem to result in as many negative dysphotopsias,” he says. “I polish the anterior rims of all capsules, which I think helps. It certainly reduces scarring and makes IOL repositioning or lens exchanges easier in the future, if indicated. I follow these patients closely. I have seen self-referred patients who felt like their surgeons didn’t believe they were experiencing these effects.”

Rewards of Vigilance

Like his colleagues, Dr. Chu recommends vigilance when evaluating vision quality throughout the postop period.

“You can have patients whose cataract surgery outcomes are excellent, but remember that they can still have poor vision quality because of meibomian gland disease, aqueous-deficient dry eye and related issues,” he says. “Identifying all potential issues from the front of the eye to the back of the eye—possibly involving the tear film, cornea, lens, capsule, retina and even the vitreous—is always important to ensure the highest quality of vision. Yes, even a vitreous floater can significantly degrade quality of vision. So every medium of the eye is important when you’re assessing patient satisfaction and the definition of vision that has the potential to go beyond perfect.”

Dr. Hatch is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision and Kala Pharmaceuticals. Drs. Shafer, Lee, Chu and McKee report no relevant financial disclosures.