Here, cataract experts discuss their choices of IOL fixation in the absence of capsular support.

ACIOLs

Anterior chamber IOLs supported by the chamber angle require good endothelial health and a normal anterior chamber depth. “Advantages of this technique include the relatively quick operating time and the straightforward surgical procedure,” says Kevin Rosenberg, MD, of Retina Vitreous Surgeons of Central New York and clinical assistant professor at SUNY Upstate Medical University. Modern flexible open-loop haptics and anteriorly vaulted optics help make ACIOLs beneficial for many patients, although they may be better suited to mature eyes.2 “Though rarer now with better ACIOLs, uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome still occurs. In addition, there is a possibility of cystoid macular edema occurring in these patients,” Dr. Rosenberg adds. “I would avoid inserting ACIOLs in patients with a history of corneal issues, glaucoma, or in the setting of significant iris trauma.”

George A. Williams, MD, chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., and clinical professor of biomedical sciences at The Eye Research Institute of Oakland University in Rochester, Mich., thinks many patients can do well with modern ACIOLs. “My exceptions are patients with endothelial compromise, glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy,” he says.

“The decision regarding which type of IOL to use varies on a case-by-case basis, and there are certainly patients for whom I still find myself favoring an ACIOL,” says Ehsan Rahimy, MD, a vitreoretinal surgeon with the Palo Alto Medical Foundation in California. He adds that the choice is dependent on multiple factors, including comorbidities such as glaucoma.

Garry P. Condon, MD, chair of the ophthalmology department at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, and professor of ophthalmology at Philadelphia’s Drexel University School of Medicine, believes that anterior chamber lens implantation is on the decline, but he also acknowledges that “a lot of studies aren’t conclusively suggesting that anybody’s suturing technique is better than a modern anterior chamber lens implantation.” He says that surgeons are gravitating toward more posterior lens placement methods: “For patients who have lens implantations now, their expectations and our desire to deliver a more optically correct visual system are leading us away from anterior chamber lenses, where there are bigger incisions, a lot more astigmatism with suturing and a slower visual recovery.”

Iris-Fixated IOLs

Dr. Condon adds that in his hands, an iris-sutured posterior chamber IOL procedure is more efficient than an ACIOL implantation. “My iris suture fixation technique requires a small incision, just two iris sutures and one corneal suture,” he states. Dr. Condon helped lead the growth of iris fixation—historically indicated for repositioning dislocated lenses—in IOL exchanges and for aphakic eyes with poor capsular support. The advent of three-piece acrylic lenses promoted this shift. “We found that we could unfold the lens and actually capture it and do everything we would if that lens was a dislocated lens. That was certainly a nice option, considering that the other choices were either to put in an anterior chamber lens or place a big, single-piece, rigid scleral-fixed lens in the sulcus,” he says.

Over many years of procedures, Dr. Condon has developed an ideal patient profile. “I like peripheral iris-sutured lenses in older patients with average-sized anterior segments, and in particular, those who still have some elements of capsule or vitreous present in the eye that help to stabilize the lens,” he says, “We secure the haptic to the iris as peripherally as possible.”

“The main advantage of iris-sutured IOLs is the ability to fixate a dislocated IOL to the iris without having to exchange the IOL,” notes Dr. Rosenberg. “Disadvantages include the potential for causing a hyphema, either intraoperatively or postoperatively.”

“As a retina specialist, I have seen patients with cystoid macular edema, recurrent bleeding or UGH syndrome following iris fixation,” notes Dr. Williams. Dr. Condon concurs that iris suture fixation entails some risks. “The core of the uveal tract is there, and that’s where the blood supply is, and it’s susceptible to inflammation,” he says. “It’s very delicate when you’re working with the iris, because it’s so easy to tear it and make it bleed.” Even a properly sutured iris-fixated PCIOL will have some mobility inside the eye, so the potential exists for mechanical trauma from pseuodophacodonesis, which is one reason Dr. Condon generally avoids them in younger patients.

Dr. Rosenberg has concerns about suture longevity with this method. “Polypropylene, the suture typically employed in iris-fixated IOLS, may break over time, requiring yet another surgical procedure down the road,” he notes.

“The suturing technique that I use is a modified McCannel suture, but utilizing a Siepser sliding knot for additional security,” Dr. Condon says. “One of the problems that people have encountered is that while using a simple modified McCannel suture with both ends of the suture pulled up, the knot is tied on the outside of the eye,” he says. “To secure the haptic to the iris, a simple modified McCannel suture, where the suture is brought outside the eye and tied, does not work as well as a sliding Siepser knot, where the entire knot slides into the eye more effectively. The risk of having the haptic slide through the suture knot is also less with the Siepser knot,” he says.

Dr. Condon doesn’t alter IOL power calculations when using iris-fixated IOLs, because he says the effective lens position ends up approximating that of a conventionally captured IOL. “As Ike Ahmed and the folks at Moran Eye have demonstrated, when we prolapse the optic of the lens back through the pupil, the haptics commonly pop back behind the ciliary processes. This vaults the lens posteriorly, and also lends a little bit of stability to it because the haptics are now up against the back side of the ciliary processes,” he explains. “That’s why, in most cases where we do this technique, we recommend using the same lens power than we would use if we were putting it in the capsular bag.”

Less commonly used in the United States, the sutureless iris-claw IOL is inserted through an approximately 5-mm incision and attached to the mid-peripheral iris using an enclavation needle to grab iris tissue between claws on either side of the lens while the pupil is constricted with a miotic.

A study of Artisan IOL posterior enclavation with two-year follow-up showed good visual outcomes, with no intraoperative and few postoperative complications.3 Noting “interesting and encouraging results” with lobster-claw lenses in other surgeons’ hands, Dr. Rahimy says, “I may potentially add this to my armamentarium in the future.”

Scleral-fixated PCIOLs

Suturing an IOL to the sclera is perhaps more technically demanding than the other techniques discussed here, but it has the advantages of durability and security, thanks in part to the haptic fixation points on PCIOLs.

Dr. Williams prefers trans-scleral fixation of the haptics of Alcon’s MA60 or MA50, both three-piece PCIOLs. “When I suture, I use 10=0 Prolene with a CIF-4 needle (both Ethicon),” he explains. He adapts his approach to each eye, though. “The primary factors I consider are the type of IOL that is dislocated, the extent of the dislocation and the status of the capsular bag. For a partial dislocation of a one-piece IOL in the bag, I prefer trans-scleral suture fixation,” he says. For complete dislocation of a one-piece lens including the capsular bag, however, he prefers replacing it with a scleral-fixated three-piece IOL. If there is retinal pathology, he will wait for the eye to quiet down before doing a secondary procedure. “I will leave the eye aphakic if there is an associated retinal problem, such as a retinal detachment that will require air or gas. Once the retinal detachment is fixed and stable, I will perform a secondary PCIOL placement via trans-scleral fixation,” he says. Dr. Williams adds that for secondary scleral-fixated lens implantation, he typically calculates a lens power to target 1 D of myopia.

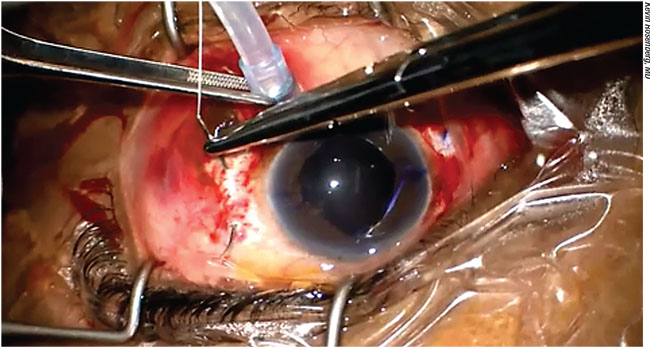

|

| Suture pass using CV-8 Gore-Tex during scleral fixation. To mitigate the risk of infection arising from erosion of subconjunctival sutures, Jamin Brown, MD, has developed a novel Gore-Tex technique that results in a completely buried suture. |

“If I have to put in or exchange an intraocular lens, I’m commonly going to a scleral-fixation approach, typically with the Akreos AO60, or the EnVista (both Bausch + Lomb) and Gore-Tex suture (W.L. Gore Medical; Elkton, Md.),” says Dr. Condon. “I like being able to put them through a small incision,” he says. “I’ll preload the lens with sutures and put it in the injector, and squirt it in the eye with all the sutures hanging out of the incision. Then I’ll bring them in from the outside in, going through the sclera and pulling each suture in and out and then tying it.” With the EnVista, he has taken to modifying the IOL. “Recently, I’ve been cutting the haptics off and just using the little hole in the haptic right next to the haptic-optic junction—loading that with strands of Gore-Tex, squirting the whole thing through a 2.4-mm incision and suturing it to the sclera, with zero in the way of astigmatism,” he reports.

Dr. Rosenberg and Dr. Rahimy both consider scleral suturing of the Akreos lens with Gore-Tex their preferred method for eyes without capsular support. “This lens has four-point fixation and is therefore quite stable and the surgical procedure is straightforward,” says Dr. Rosenberg. “The CV-8 Gore-Tex sutures are strong and easy to handle. In a patient without capsular support and a history of glaucoma, corneal issues, or iris trauma, this is definitely my technique of choice. Additionally, in young patients I prefer to implant these lenses, as opposed to ACIOLs, because I think they are probably a more stable long-term option.

“Despite its advantages, this technique is not without its drawbacks. After this technique the patient is left with a subconjunctival suture. If the conjunctiva erodes postoperatively, then this suture serves as a potential route for bacteria to enter the eye and cause endophthalmitis,” Dr. Rosenberg continues. “I am concerned with any technique that leaves suture or haptic in the subconjunctival space. In our group, we have seen both haptics and Gore-Tex erode through the conjunctiva, once resulting in endophthalmitis.”

Dr. Rosenberg credits his partner, Jamin Brown, MD, with developing a Gore-Tex suture technique that sidesteps this risk and complication by completely burying the suture. “Essentially, the Gore-Tex CV-8 needle is passed partial-thickness between the sclerotomies as a first step, and then the suture is back-fed through the eye and the Akreos eyelets,” he explains, adding that Dr. Brown’s method also helps to prevent the sutures from getting tangled in the eye. (A video of the technique accompanies the online version of this article.) Dr. Rahimy, who with colleagues has published a step-by-step guide to his ab externo technique with the Akreos AO60 and CV-8 Gore-Tex4 says that despite increased technical demands, “there is a rapid learning curve” to his method.

“Patient selection is key,” he explains, “especially if this is one of your first times attempting this technique. You want to set yourself up for success. The relative ease, or difficulty, of handling the conjunctiva (especially closure at the end of the case) is an often overlooked, but critical, step that can make all the difference in terms of the case length as well as the surgeon’s perception of the procedure’s difficulty. Accordingly, preoperative conjunctival assessment is important, especially if the patient has had previous ocular surgery in which the conjunctiva was manipulated and may be potentially friable or scarred down, i.e., scleral buckling, multiple vitrectomies or a glaucoma filtration procedure with trabeculectomy or tube shunt.”

Surgeons note some other factors to consider when approaching these cases:

• Handle haptics with care. “For the trans-scleral fixation technique using forceps, it is critical that the forceps engage the haptic as close to the end of the haptic as possible, and to slide the valved cannula up the forceps before externalizing the haptic,” says Dr. Williams.

• Talk to patients about their visual expectations. Although this is crucial prior to any IOL implantation, Dr. Rahimy stresses the importance of realistic discussions in these complicated cases. “I explain to the patient that the targeted visual outcomes are a little less predictable with our secondary IOL techniques (especially if a lens is being removed and replaced), and that there is a high likelihood of needing additional refractive correction postoperatively, no matter how good their vision was before, when they had the in-the-bag IOL,” he says.

• The line between anterior-segment and vitreoretinal skills is blurred. “The pars plana is the most unappreciated anatomical part of the eyeball for the anterior segment surgeon,” quips Dr. Condon. “We can go through it, we can tie things to it to scleral-fixate lenses. But to be versed in this stuff, you have to be comfortable with some pars plana vitrectomy work: That’s where this goes beyond the scope of general anterior segment surgery. Comfort with the micro forceps and pars plana instrumentation is important if you want to feel comfortable doing scleral posterior chamber IOL fixation,” he says.

• Beware IOL opacification. “The Akreos lens is hydrophilic, and there have been case reports of lens opacification of this IOL after intraocular gas use,” cautions Dr. Rosenberg. “Therefore, some surgeons are wary of using this lens in a setting where gas may be used, as in retinal detachment repair or in a DSAEK procedure. I have used SF6 gas with this lens and did not have any postoperative lens opacification, but there is definitely the potential for this complication.”

Glue-assisted Scleral Fixation

Fibrin glue and trans-scleral scarring, rather than sutures, secure the IOL in this method. Dr. Amar Agarwal, MS, FRCS, FRCOpth, chairman of the Agarwal group of eye hospitals in Chennai, India, has pioneered and refined the technique.5,6 He performs only glue-assisted IOL implantations for out-of-the-bag fixation; he believes his method inhibits pseudophacodonesis better than ACIOLs or sutured PCIOLs. “Imagine if we glue a lens to a camera body: Both the lens and the body of the camera would move in unison,” he says. “ In the eye, potential movement of the IOL is thought to cause disturbance in the vitreous cavity, or in ACIOL cases, may cause release of inflammatory tissue from the iris, leading to prolonged CME,” he says.

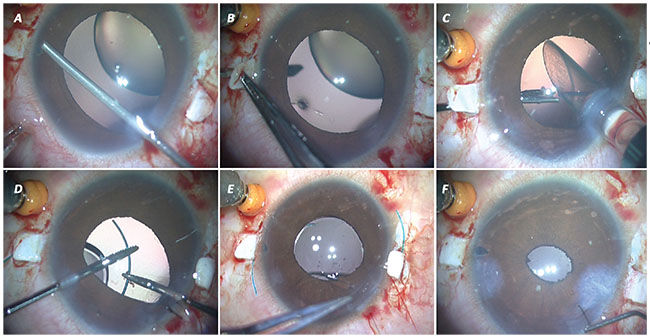

|

| Glue-assisted scleral IOL fixation in an eye with a subluxated lens due to Marfan’s syndrome. A: Vitrectomy and peripheral iridectomy near scleral flaps. B: Anterior sclerotomy created with 22-ga. needle. C: After lensectomy, three-piece IOL in the AMO injector. The glued forceps is ready to grasp the haptic tip. D: Leading haptic externalized; two glued forceps used bimanually. E: Both haptics externalized. F: Haptics tucked in Scharioth pocket; fibrin glue applied. |

Dr. Agarwal uses the handshake method using two glued IOL forceps, after gently injecting a foldable three-piece IOL into the eye with one hand using an AMO injector. The surgeon always has hold of at least one haptic before each is bimanually guided into the proper sclerotomy. “Fear of the IOL falling into the vitreous cavity is not there, as the tip of the leading haptic is caught with the forceps, and the trailing haptic is still outside the eye,” he says, adding, “The important step is to grab the tip of the haptic with the end-opening forceps,” to prevent breakage and snagging during externalization.

Dr. Agarwal’s “quintet” of pointers to optimize trans-scleral glued IOL surgery outcomes is as follows:

1. Vertical glued fixation: In eyes with a white-to-white measurement greater than 11 mm, Dr. Agarwal makes his flaps at 6 and 12 o’clock, rather than 9 and 3 o’clock. “The vertical cornea will always be shorter than the horizontal, so one will have more haptic to tuck and glue,” he says.

2. Infusion with trocar anterior chamber maintainer: “This allows continuous maintenance of the globe without encroaching upon the surface of the cornea, leaving the entire working space at the surgeon’s disposal,” he explains.

3. Peripheral iridectomy: Dr. Agarwal does this at the proposed sclerotomy sites, using a vitrector at 20 cuts per minute and low vacuum setting. “In large eyes it is advisable to do anterior sclerotomy,” he says. Iridectomy keeps peripheral iris tissue clear of potential damage from the passage of the needle and forceps from the sclerotomy site.

4. Anterior sclerotomy: “The fourth part of the quintet is anterior sclerotomy performed 0.5 mm away from the limbus beneath the scleral flaps,” says Dr. Agarwal.

5. Pupilloplasty: Dr. Agarwal says the last step of his quintet is “Single-pass Four Throw (SFT) pupilloplasty, negating any chance of optic capture.”

No Clear Winner

Just as there are multiple causes of poor capsular support, there are many alternative ways to fixate an IOL that can produce good visual outcomes. Eye anatomy, ocular pathologies, visual potential and surgeon comfort are all guideposts in the decision-making process.7 It’s also important to be aware of situations in which a particular approach is comparatively contraindicated. “One must be adept at several different techniques and be willing to adjust plans on the fly during surgery,” says Dr. Rahimy. “As one of my mentors in fellowship was fond of saying, ‘Take what the eye gives you.’ ” REVIEW

Dr. Rosenberg is a member of Allergan’s advisory board. Dr. Condon is a consultant and speaker for Alcon, Allergan and Microsurgical Technologies. Drs. Williams, Rahimy and Agarwal report no financial interests relevant to this article.

1. Wagoner MD, Cox TA, Ariyasu RG, Jacobs DS, Karp CL. Intraocular lens implantation in the absence of capsular support: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2003;110:4:840-59.

2. Bergman M, Laatikainen L. Long-term evaluation of primary anterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in complicated cataract surgery. Int Ophthalmol 1996-1997;20:6:295-9.

3. Anbari A, Lake DB. Posteriorly enclavated iris claw intraocular lens for aphakia: long-term corneal endothelial safety study. Eur J Ophthalmol 2015;25:3:208-213.

4. Rahimy E, Khan MA, Gupta OP, Hsu J. Gore-Tex sutured intraocular lens: A beginner’s guide for scleral fixation of posterior-chamber IOLs. Retinal Phys 2016;13:36-8.

5. Agarwal A, Kumar DA, Jacob S, Baid C, Agarwal A, Srinivasan S. Fibrin glue-assisted sutureless posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in eyes with deficient posterior capsules. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:9:1433-8.

6. Narang P, Agarwal A. The “correct shake” for “handshake” in glued intrascleral fixation of intraocular lens. Indian J Ophthalmol 2016; 64:11:854-856.

7. Dajee KP, Abbey AM, Williams GA. Management of dislocated intraocular lenses in eyes with insufficient capsular support. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2016;27:3:191-5.