Today, anyone working in medicine (or staying in a hospital) would find it hard to miss the extraordinary amount of waste produced by our health-care system. That’s certainly true when it comes to surgery, and cataract surgery—one of the most common surgeries performed around the world—is no exception. In fact, not only does cataract surgery usually result in the discarding of contaminated materials, it often results in unused materials being discarded as well. In addition, manufacturing those materials produces all kinds of pollution that exacerbates climate change and impacts the health of those exposed to the polluted air and water.

“We’re all trying to manage patients efficiently with minimal cost, but we should also be thinking about managing them in ways that are the least damaging to the environment,” says Joel S. Schuman, MD, FACS, director of the NYU Langone Eye Center and chairman of ophthalmology at the New York University School of Medicine, who co-authored one of the key papers focused on the Aravind Eye Hospital in southern India, known for performing cataract surgery with minimal creation of waste and pollution.1 “We produce a lot of waste, especially in surgery—roughly 20 times the waste of a given operation at Aravind. There’s no really good reason for that, except that we make a lot of assumptions about what we need to do in order for the surgery to be safe. What they’re doing at Aravind puts the lie to a lot of the precautions that we take. I think there are a lot of lessons we can take home from their experience.”

“Defensive medicine is a waste of expensive—and for many societies, precious—resources,” agrees David F. Chang, MD, a clinical professor at the University of California, San Francisco. “I believe the same can probably be said about many of our operating room regulations. Although they’re intended to reduce the risk of surgical infection, the benefit of some wasteful, but required, practices is unproven by any study. And added to many wasted health-care dollars is the wasteful carbon footprint associated with these practices. Indeed, the health-care sector produces approximately 10 percent of the total greenhouse gases and air pollutants in the United States.1 One of the largest problems is that operating room staff—surgeons and nurses—are not allowed to use their discretion with respect to reusing some products or devices.”

Uncovering the Problem

One of the people credited with spurring interest in this field is Cassandra L. Thiel, PhD, currently an assistant professor at the New York University School of Medicine. While earning her PhD, Dr. Thiel learned to use a tool called “life-cycle assessment.” “This process takes any product or process and analyzes the steps and stages in its life cycle, from the original extraction of materials and manufacturing to its use and disposal,” she explains. “Then, it sums up all the emissions and waste produced at each of those points.

“Initially I applied this tool to so-called ‘green buildings,’ ” she continues. “Then I met a physician who was upset about the amount of garbage produced when she did surgery. She wanted to reduce her carbon footprint at work and was trying to determine what steps she could take to accomplish that. The common suggestion you hear in hospitals is, ‘Let’s recycle more.’ She wasn’t satisfied with that answer because there was no data associated with it. I thought that the life-cycle assessment tool could be helpful in this situation.”

|

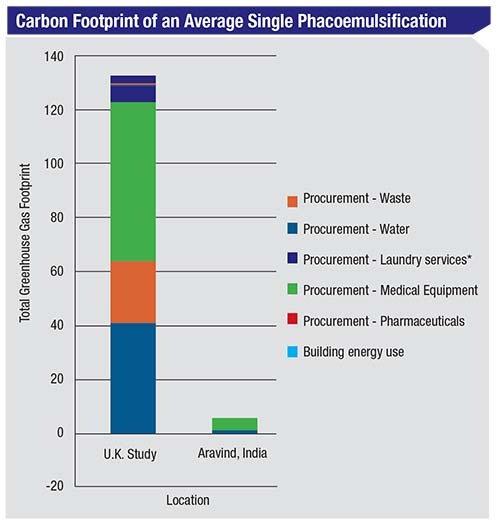

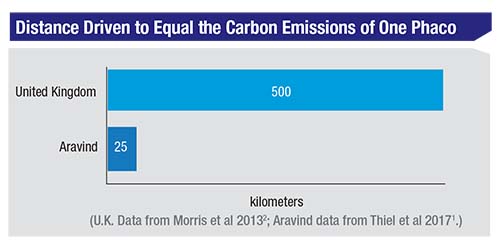

| A comparison of factors contributing to the carbon footprint associated with cataract surgery in the United Kingdom and the Aravind Eye Hospital in India, as determined by life-cycle assessment. (U.K. Data from Morris et al 20132; Aravind data from Thiel et al 20171.) |

Dr. Thiel and her advisor began by running some studies in her physician mentor’s field, obstetrics and gynecology. “We compared four different approaches to hysterectomy and found that the more advanced the technology—e.g., laparoscopic and robotic procedures—the more waste and emissions were generated. Beyond that, one of the major results was that the environmental emissions were coming almost entirely from the production of disposable materials.

“Not surprisingly,” she adds, “recycling would have very little impact on that footprint.”

Dr. Thiel’s interest in ophthalmology in particular was sparked by a study performed in the United Kingdom that explored the carbon footprint of phacoemulsification surgery.2 Then, she saw a TED Talk discussing the Aravind Eye Hospital in southern India. “Aravind was set up in the 1970s,” she says. “Their model was built around getting as many people through the system as possible in a safe and effective manner. In India they don’t have the same kind of legal/regulatory situation as we do in the United States, so they were able to innovate new approaches to delivering surgical care.”

Proving It Can Be Done

Dr. Thiel visited numerous ORs in the United States to observe cataract surgery methodology in America. “What I noted was that health care is provided in pretty much the same manner everywhere,” she says. “You see the same setup, the same surgical supplies; there’s not a lot of variety. Then in 2014 I received a Fulbright fellowship to go to India and live at Aravind for about four months. I observed their physical setup, what was being done in the OR and what supplies they were using. Then, we did a full life-cycle assessment of their process.

“The most striking result was that one cataract surgery at Aravind only produced about 5 percent of the carbon emissions found for cataract surgery in the U.K. study,” she says. “Perhaps most remarkable, Aravind’s outcomes are on par with—or better than—United States cataract surgery outcomes.3-5 That means that it’s possible to design your surgical-care pathway in such a way that it drastically reduces the carbon emissions required for that surgery, while still providing the same quality in terms of outcomes.”

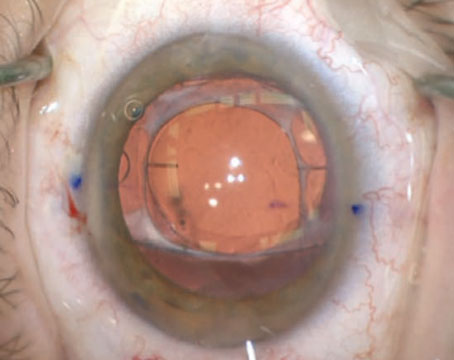

Dr. Thiel says the main reason for that result was the way Aravind set up its surgical-delivery system. “Patients go through the process almost like a factory assembly line,” she explains. “They’re flowing through the system constantly. The surgical staff is never waiting for a patient. The OR has two beds per physician; one bed is being prepped while the other is in use for surgery. The surgeons rotate back and forth between the two beds, using one microscope and one phaco unit.

|

| At the Aravind Eye Hospital the surgical staff is never waiting for a patient. The OR has two beds per physician; one bed is prepped while the other is in use for surgery. The surgeons rotate back and forth between the two beds, using one microscope and one phaco unit. |

“Aravind employs ‘task shifting’ by using highly trained mid-level ophthalmic professionals to conduct many of the tasks in the operating room,” she continues. “Two technicians who are not scrubbed-in help escort patients in and out and help with some of the prep and postoperative work. Two others are scrubbed in—one per table. They’re in charge of delivering surgical supplies and making sure that everything is sterile. The physicians are just doing the surgery, cut to close; they don’t do any of the pre- or postop stuff. Of course, they take a time out to make sure they’re doing the correct eye and so forth, but otherwise the surgeon just does the actual surgery. This process makes the duration of the cases very short. I watched one of their top surgeons do about 40 surgeries in about four hours. That’s especially impressive when you consider that these cases were often challenging patients who were clinically blind from the cataract.”

Dr. Schuman notes that it’s possible to do some things in India that would be much harder to do in the United States. “For instance, having multiple patients in the OR simultaneously would be frowned upon here,” he says. “It’s not because there’s any evidence that doing so is a bad idea; it’s because there’s an assumption that we’d increase the risk of infection.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Schuman believes there’s a lot of opportunity to improve the efficiency and decrease waste in our surgeries. “We’re not even close to being optimized,” he says. “If you look at a place like

Aravind, they have efficiency down to a science. Their doctors do a very high volume of surgery of one specific type—cataract surgery. One surgeon may do 50 or 60 cases before lunch. They can do this because there’s not a wasted movement in the OR. Then, along with the efficiency of the operation comes a savings in terms of both supplies and also a reduction in the creation of waste.”

Reusing Tools in the OR

Dr. Thiel notes two factors that contributed to the efficiency of the Aravind process. “They had a standardized instrument tray, with virtually no variability in what the surgeons were using and how they used the tools,” she says. “That means that purchasing supplies is pretty standardized. Also, they were reusing almost everything. The phaco tips were reused; the blades in some cases were reused. In some cases even the gloves were reused, which is not something I’d recommend here in the States. To save the time it would take to change gloves between cases, they’d use a sterilizing gel on the gloves before moving on to the next patient. While this may sound dangerous, recent studies of the Aravind Eye Care System documented an endophthalmitis rate of 0.02 percent in 555,550 consecutive cataract surgeries using intracameral antibiotics.2-4 That’s better than the current rate in the United States.”

Dr. Chang points out that published data strongly suggests that reuse and reprocessing of many “single-use” instruments and supplies does not pose a significant infection risk. “We’ve published the extremely low endoph-thalmitis rates at the Aravind Eye Care System,” he says.3 “Their endophthalmitis rate in more than 237,000 consecutive phacos receiving intracameral moxifloxacin was 0.01 percent, which is lower than the current IRIS registry endophthalmitis rate of 0.07 percent. What’s striking about this data is that Aravind routinely reuses gowns, gloves, blades, cannulas, phaco tips, capsulotomy cystotomes, and irrigation solutions and tubing. These are all single-use items in the United States, where the licensing and regulatory agencies don’t give surgeons any discretion to reuse them.”

Dr. Chang is co-chair of the ophthalmic instrument cleaning and sterilization (OICS) task force, a collaboration between the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, Outpatient Ophthalmic Surgery Society and the American Academy of Ophthalmology. “Our recently released guidelines point out that there is now published data showing that reuse of certain instruments and products is not associated with high endophthalmitis rates,” he says.6 “We also cited studies performed by OICS task force members that failed to show any dangerous ultrastructural changes resulting from multiple simulated uses of phaco tips.7 Because of how heavily regulated our hospital and ASC operating rooms are, it really falls on industry to permit responsible reuse of instruments and products via their labeling. However, profitability and liability create strong disincentives to doing that.”

Switching to Reusables?

Many surgeons are coming to appreciate the problem and looking for things they can do to move cataract surgery in a “greener” direction. One obvious possibility is to consider using fewer single-use instruments and accessories. “I think the health-care system in the United States is way overboard in terms of single-use equipment,” says Dr. Thiel. “We’re not looking at the long-term consequences of this. We’re paying more for the instruments and we’re generating a lot more waste, including a lot of plastic. We already know we have a huge problem with plastic in the environment. In addition, producing all of those items from virgin plastics and metals has an impact on the environment, which has an impact on our health. We’re not just talking about climate change; we’re talking about air pollution and water pollution.”

Dr. Schuman agrees. “Whenever there’s a problem involving infection, or something comes up in medicine that involves sepsis or sterility, the answer—too often, I think—is disposable instruments or supplies,” he says. “That is not always the best answer. It may be that you could do just as well with a nondisposable that’s properly cleaned and sterilized. Furthermore, the quality of a single-use instrument is often not as good as a nondisposable one. And working with reusable instruments does not make the surgery take longer—the experience at Aravind definitely shows that.

“I think we need to take a step back and look at how we’ve been addressing problems having to do with patient safety,” he continues. “We need to use an evidence-based approach, instead of simply assuming that we need to use disposable devices or instruments to ensure patient safety.”

“Making this kind of change isn’t just about decreasing waste and pollution; it’s also value-based medicine.” — Joel Schuman, MD |

Given that switching back to reusable surgical equipment is an obvious way to address this problem, why aren’t more surgeons doing so? Two practical concerns are a big part of the answer.

“Switching supplies is always a little challenging, because it’s tied to the contracts that exist in your institution,” Dr. Thiel points out. “I’ve heard stories from the food service industry about institutions that can’t get rid of soft drinks because they have to wait five years for the current contract to expire. That happens with surgical instrumentation, too. Of course, there are plenty of reusable supplies out there. If you’re willing and able to go through the negotiations with your institution and the manufacturers, please do. If not, that’s OK, but you can start getting people thinking about it before the next contract comes up. If you succeed, there might be enough motivation to make the switch to reusables when that happens.”

Another factor that has had a lot to do with the widespread use of single-use tools is the fear of being sued should something go wrong. “In any surgery, I think there’s an expectation that everything will go well, and usually it does,” says Dr. Schuman. “However, there’s a tendency—especially in the U.S.—to assume that if things don’t go well, it’s somebody’s fault. One of the side effects of this is that if you’re doing things in an unconventional way, you’re more susceptible to legal action than if you’re doing things the same way as everybody else. That inhibits the introduction of different ways of doing things.

“Today,” he continues, “we have organizations that say, ‘In order to reduce risk and increase safety we have to use disposables.’ In fact, there’s no evidence that using disposables is safer. But if you say, ‘OK, this doesn’t really reduce risk, so I’m going to go back to working with reusable instruments,’ you’ve opened yourself up to legal action if something goes wrong. Something always goes wrong eventually, because we don’t live in a perfect world. Then, the first question you’re going to get is, ‘Why aren’t you doing this the way everybody else is?’—even if the problem didn’t come from reintroducing reusables.”

Other Strategies That Can Help

Taking these steps can also reduce waste and pollution:

• Standardize your equipment lists. “Sit down with all of the other ophthalmologists in your group and figure out what’s the least amount of materials you need to do cataract surgery,” says Dr. Thiel. “Go through your custom-pack lists, your physician-preference cards, and look for items you don’t actually use that much. Those items could be available on an ‘as needed’ basis. You might even find items you used in the past that you rarely use today, items that shouldn’t even be on the list.”

• Tell your surgical team not to open anything unless you explicitly say it’s needed. “The less you bring into the OR, the better it is overall,” notes Dr. Thiel. “We see a lot of waste in the OR custom packs. I’ve observed that physicians in the same institution often use identical custom packs, but one physician might use two of them while another might only use a quarter of one. Sometimes the surgeon is missing one instrument, so the surgical team opens up another custom pack to grab that one item out. That’s the kind of waste that can be avoided if you have better communication with your team—and you let your team know that one of your priorities is reducing waste. Your staff should know not to open something just because you might need it. You want them to confirm that it’s needed before they open another pack.”

• If possible, dedicate each OR to one type of surgery exclusively. “One reason Aravind is so efficient is that their ORs do only one type of surgery per room,” says Dr. Schuman. “An OR that’s only used for one purpose can function more efficiently than one that’s used for different types of cases throughout the day. If you’re in a hospital OR, the personnel might be constantly switching throughout the day between different types of operations—or even different disciplines. That’s going to be much less efficient than having a room that’s just doing cataracts all day, and having personnel who staff that room on a regular basis and always do that type of case. Decreasing the variability would help to increase the efficiency with which the cases can be done—not to mention increasing the predictability of outcomes.”

• Consider giving your cataract surgery patient the eye drops used in the OR to take home. “This simple step would reduce the amount of waste tremendously,” Dr. Schuman notes.

• See what’s available in terms of single-use device reprocessing and systems for recycling. One idea that’s arisen to help offset some of the consequences of excessive use of single-use equipment is single-use device reprocessing. “There are third-party companies that will take single-use devices, break them apart, clean and sterilize them, test them and sell them back to hospitals for perhaps half the price of the original,” says Dr. Thiel. “This reprocessing market is becoming much more popular in the U.S. as a cost-saving method. The thinking is that it’s more environmentally friendly, because you’re clearly reducing waste. (We haven’t yet conducted life-cycle assessments of this process, so we don’t know about the level of emissions associated with it.) At this point, I’m not sure how many ophthalmic tools can be reprocessed, but if you find options that could reduce waste, advocate for using them.”

Dr. Thiel notes that the availability of this service has (predictably) resulted in a cat-and-mouse game in the industry. “Often, the original instrument manufacturer will try to change the design just enough so that the reprocessors have to get a separate FDA approval to be allowed to reprocess the device,” she says. “It’s a bit of a challenge for the reprocessing industry to keep up when the manufacturers are trying to discourage reprocessing.”

|

• Consider donating unused supplies. “In some situations there may be ethical issues here, but in many cases this can be done,” says Dr. Thiel. “It will at least give those supplies some lifespan after being left unused in the OR.”

• Get the people around you excited about reducing waste and increasing efficiency. “You don’t have to preach about carbon emissions,” notes Dr. Thiel. “It can be as simple as asking, ‘How can we use fewer supplies?’ If you spread the word, you’ll find that everyone will have ideas that could help. Eventually, that ground-level engagement could potentially start a movement at your institution and get people from the top down prioritizing some of these things.”

• Ask your ophthalmology organizations to get involved. “Changing this situation will require the efforts of more than one person,” Dr. Schuman says. “The support of organized medicine will be critical to making these changes. This is more than a medical issue; creating change will require legal-political decision-making. Our organized ophthalmology associations need to take up the mantle and make the effort on our behalf. Those organizations can develop white papers supporting the types of innovation that would reduce surgical waste and increase efficiency. That would lend a lot of credence to groups and individuals that wish to adopt those methods.”

Looking to the Future

With the world seeing more and more unintended consequences of ignoring our prolific waste creation and oversized carbon footprint, one might well wonder: What will happen if nothing about the way we currently perform cataract surgery changes? “I see an increase in costs and production of waste,” says Dr. Schuman. “Aside from other consequences, the money to keep paying for this is simply not there. We have to find ways to do this work more efficiently and using fewer resources. Those ways are available; we just haven’t adopted them in the U.S.”

Dr. Thiel notes that in her experience, no doctors are happy with how much garbage their surgeries create. “Waste is everywhere in medicine,” she notes. “Ophthalmologists as a group have expressed the most interest in this of any medical specialty I’ve spoken to. Maybe that’s partly because ophthalmologic surgery has a relatively low infection risk compared to something like orthopedic surgery, where there’s blood everywhere. That means there’s more opportunity to make changes that are safe and effective and don’t compromise care than there would be in some of these other clinical settings. That’s one reason I think ophthalmology can lead the way to start making some of these changes, and demonstrate that they’re safe and effective.”

“Green surgery is something we should all be thinking about,” Dr. Schuman concludes. “This is not just about helping the individual patient—we should be trying to help the planet as well. Besides, making this kind of change isn’t just about decreasing waste and pollution; it’s also value-based medicine. This is about consuming fewer resources in order to produce a good outcome.” REVIEW

Drs. Schuman, Chang and Thiel report no financial ties to anything discussed in this article.

1. Thiel CL, Schehlein E, Ravilla T, et al. Cataract surgery and environmental sustainability: Waste and lifecycle assessment of phacoemulsification at a private healthcare facility. J Cataract Refract Surg 2017;43:11:1391-1398.

2. Morris DS, Wright T, Somner JE, Connor A. The carbon footprint of cataract surgery. A Eye (Lond) 2013;27:4:495-501.

3. Haripriya A, Chang DF, Ravindran RD. Endophthalmitis reduction with intracameral moxifloxacin prophylaxis; Analysis of 600,000 surgeries. Ophthalmology 2017; 124:768–775.

4. Chang DF, Haripriya A, Ravindran RD. Reply to letter RE: Endophthalmitis reduction with intracameral moxifloxacin prophylaxis: An analysis of 600,000 surgeries. Ophthalmology 2017; 124:e78–e79. Available at: http://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(17)30748-0/pdf.

5. Haripirya A, Chang DF. Intracameral antibiotics during cataract surgery: Evidence and barriers. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018; 29:33–39.

6. Mamalis N, Chang DF. Guidelines for the cleaning and sterilization of intraocular surgical instruments. J Cataract Refract Surg 2018;44:6:675-676.

7. Tsaousis KT, Chang DF, Werner L, et al. Comparison of different types of phacoemulsification tips. III. Morphological changes induced after multiple uses in an ex vivo model. J Cataract Refract Surg 2018;44:1:91-97.