Office-based cataract surgery offers several benefits over procedures performed in an ambulatory surgery center, and some surgeons believe this practice will become more common in the next few years.

|

|

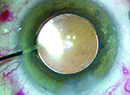

The in-office operating room in the practice of Omaha surgeon Lance Kugler. |

“From a big picture perspective, it’s inevitable that we’re going to be moving towards doing intraocular surgery in an office-based OR,” says Omaha’s Lance Kugler, MD. You have a situation where you’ve got something that’s better for patients, for surgeons, and for third-party payers, and when those things align, it becomes inevitable that that’s the direction things are going to go.”

However, some surgeons are skeptical and are concerned about patient safety during office-based procedures. Here, both sides share their perspectives.

The Advantages of Office-Based Surgery

Jason Stahl, MD, who is in practice in Overland Park, Kansas, says his practice doesn’t participate with insurance, but he has been providing in-office refractive lens exchange and refractive cataract surgery for almost two years. He mostly performs refractive lens exchange, and he does bilateral, simultaneous surgery. “It’s been a really great addition to our practice because it’s very similar to the LASIK encounters that we have with patients, where we walk them in, we do their surgery, and they walk out,” he says. “It’s very relaxed, and patients really enjoy having the procedure in our office. We occasionally have patients who have one eye done in an ASC and the other eye done in our office-based OR. All of these patients have commented that they preferred the office-based procedure. We are able to do the surgery with simply a little bit of Valium. No IVs are given. It’s just very comfortable.”

He adds that the main reason his practice decided to perform in-office IOL surgery was to better control the patient experience and to provide more of a LASIK-type experience for patients rather than going into a cold, sterile environment at an ASC. “We try to take it to the next level by doing it in the office,” Dr. Stahl says.

Dr. Stahl had his doubts about whether the procedure could be done with just Valium and whether the patient would be able to just walk in and out. “Until I actually did it, it was kind of hard to believe,” he says. “For 25 years, I’ve done my cases in an ASC, and it was hard for me to believe that we could simply give these patients 5 mg of Valium, walk them in, do the surgery and walk them out. But, then it made sense, because they’re in a familiar environment. They’re not on a bed being wheeled in and out. The patient already has less anxiety going into it than they would in an outpatient surgery center environment, and that’s why they do so well with just very minimal sedation.”

According to Dr. Kugler, there are cost benefits as well. “In-office procedures are less expensive for patients, too,” he says. “ASCs were a wonderful invention because they brought costs down compared to hospitals, but there are a lot of costs to running an ASC that don’t apply to ophthalmology. An in-office operating room that’s designed only for eyes can improve your outcomes and safety standards relative to other centers. An office-based OR allows surgeons to maximize efficiencies in terms of time, schedule, staffing and supplies. And that’s good for patients, surgeons and payers.”

He adds that patients love having the procedure in the same facility where they see their surgeon. “I didn’t really appreciate that this was going to be the case until we had our own in-office suite,” he says. “For years, I went to an outpatient ASC across town. It was a really nice center with good equipment, and I thought it was comfortable for patients, but I learned that from the patient’s perspective, it was a big deal because there was this new, third-party facility that they had never heard of or considered. This induced anxiety and a whole other layer of concern. Whereas, if we offer the procedure in our own center, patients are much more comfortable. They see the same staff that was there for their evaluation. The staff knows the patient, and they know if there’s anything specific about them that we need to be thinking about. So, the overall experience from start to finish for the patient is much more comfortable. That’s a big advantage.”

The Cons

While proponents say there are many advantages to office-based procedures, they are not for all patients. According to Dr. Stahl, surgeons need to choose their in-office patients carefully. “If someone is very nervous, and we feel that he or she may need an IV, then we would want to do that procedure in an ASC,” he says. “Certainly, patients with significant medical histories need to be done in an ASC, where nurse anesthetists are available if there are any issues. So, at least in our practice, in-office cataract procedures are for very healthy patients who we know will do well with very minimal sedation.”

Kevin M. Miller, MD, who is in practice in Los Angeles, is concerned about patient safety and surgeon reimbursement. “The sole motivation behind this move from hospital outpatient department (HOPD)/ASC surgery to office-based surgery from the payer side, primarily driven by Medicare, is to reduce expenditures,” he says. “Safety and quality are supposed to be givens in this thinking and should’t be impacted by declining reimbursement, but everyone knows this isn’t true. An overarching issue is that the Medicare trust fund will run dry in 2024, just three years from now, and those that administer it are desperate to reduce outlays. Cataract surgery is the number one procedure by volume in the United States. Medicare and private insurers have been reducing reimbursements for cataract surgery pretty much since Medicare was established in the mid-1960s, but now they’re desperate.”

He believes that there will be quality and safety risks for patients who undergo in-office cataract procedures. “You won’t have an anesthesiologist, so if your patient is having issues such as pain or anxiety, there will be no anesthesiologist to call on to administer an intravenous solution,” he notes. “If the sublingual anxiolytic or Valium that the patient took isn’t doing the job, what are you going to do? You’re not going to stop the surgery, put the patient in an ambulance, take him or her across town to the hospital, then finish up the procedure there. I believe safety will suffer. Medicare will counter that the routine cases can be done in the low-cost office environment and higher-risk patients can be done in an HOPD or ASC, which is better staffed. The argument is that there are plenty of clean cases around, but this isn’t true. Virtually every patient in the cataract age range has ocular and systemic comorbidities and high-risk features or characteristics that put him or her at risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications. A high-risk feature might be a really dense cataract in a deep-set eye. Or, it might be that they have pseudoexfoliation or hearing difficulty. The list goes on and on. There are very few routine cases.”

In the 1980s, when cataract surgery went from the inpatient to outpatient setting, surgeons had the same concerns. “People said it was bad for patients and there would be more systemic and ocular complications,” says Dr. Miller. “However, the switch was seamless, and the complications were no different. The switch didn’t improve safety, but it didn’t worsen safety. All of this was a huge benefit to Medicare in terms of cost savings. In fact, there are plenty of anecdotes of it actually being safer for patients because now they aren’t stuck in a hospital bed where they can develop deep vein thrombosis or a pulmonary embolism. There might have been some actual benefit to getting them out of the hospital environment.”

Dr. Miller says that, on top of all this, ophthalmologists are being squeezed now in a way that they were never squeezed before. “If it weren’t for premium services, most cataract surgeons would have to close their doors,” he avers. “Premium services are keeping the whole thing afloat. Cataract surgery has become a loss leader. Once you get a patient in the door for cataract surgery, you hope he or she will choose to add on some services, such as astigmatism management or a premium lens. You’re going to receive even less reimbursement for in-office procedures, as compared to an HOPD or ASC procedure, but the supplies you will be required to maintain will be exactly the same. There is a financial risk for any practice that does this.”

According to Dr. Miller, in the 1970s, Medicare paid about $2,400 for a cataract procedure, which would be about $7,000 today in a constant-dollars analysis. “But, our reimbursement is now less than $600,” he says. “Reimbursements have gone down over 90 percent, while practice expenses have gone up at least threefold.

“I’m a skeptic that this is going to work, but we’ll see,” Dr. Miller continues. “I hate to be a naysayer. I’m optimistic about most things, but I don’t see this working on a mass scale. Anecdotes will start coming out that this or that patient had a complication and that an ambulance had to be called.”

According to Dr. Kugler, another con is that setting up your office and establishing protocols is difficult. “When we moved to an in-office suite,” he says, “I had all of these same concerns: What about the anesthesia and the compliance protocols? It is important to make sure that you’re setting it up with established protocols and that you have third-party accreditation. We hired a consulting group to do that for us. I think it’s beyond the skill set of most individual surgeons to be able to set up an in-office OR without help.” (To learn more about how some practices are setting up in-office ORs, see “Defying Economic Gravity: 10 Ways to Boost Income” in the November 2021 issue.)

The Evolution of In-office Surgeries

According to Dr. Kugler, there are many misconceptions about office-based surgery. “A lot of surgeons think there’s just a procedure room in the corner where you’re doing eye surgery,” he says. “That’s not the case at all. An office-based facility is a full operating room. It has the same or better standards as a hospital OR would have. There is a sterilization room, a clean room, a dirty room, air filtering, back-up power and everything else. It’s literally a full OR. This is important to understand, because many people are picturing a backwoods set-up, and that’s not what this is. The only difference is that your office doesn’t have the ASC certification layer that goes on top of it. For example, our OR is certified by an independent third party, but it’s not certified by Medicare. That’s the difference.”

In the early 1980s, patients typically stayed in the hospital for a week for cataract surgery. “It was a big deal and required general anesthesia,” says Dr. Kugler. “When surgeons started to perform outpatient cataract surgery, people thought it was crazy. People were actually disciplined by hospital boards for sending patients home after cataract surgery. But, after a while, everyone realized that it made sense and that it was good for payers, patients and surgeons, so they continued to do outpatient surgery in the hospital. Then, it was later moved to outpatient surgery centers to save money for the system and also to make things better for patients and surgeons. But that was considered very renegade at the time. Then, surgeons went from general anesthesia to retrobulbar anesthesia to topical anesthesia, and each one of those changes was a major disruptor. Now, going from an ASC to an in-office operating room is a similar transition, and at the same time, we’re going from monitored IV sedation to straight topical without any IV sedation. It’s just kind of the natural evolution.”

He adds that he has a nurse anesthetist in his practice about once a month, and he schedules all patients with medical conditions during this time. “If I have anybody who needs monitoring, I’ll have an anesthesia provider there in the office,” he notes. “I have that capability, but I never want to give patients more anesthesia than they need because I’ve learned that patients do better with less. They’re more nervous and they jerk around [with more anesthesia], and it’s much better to have less, which is very different than what I was taught during training, but that’s what we’ve learned.”

Dr. Kugler does more than 90 percent of his cataract procedures in his office, but there are rare instances in which he performs cataract surgery in an ASC or hospital. “If a patient has a large body mass index or if he or she needs to be transferred from a wheelchair, we don’t have the staff with the training to handle those kinds of things, so I don’t do those in my office,” he says. “But that’s very rare in my practice. Everything depends on your patient population and what percentage you can do in the office.”