“The prostaglandin class of drugs represents the most efficacious, safest and most conveniently dosed drugs that we have currently to treat glaucoma,” notes Tony Realini, MD, MPH, professor of ophthalmology at West Virginia University Eye Institute in Morgantown, W.Va. “They don’t have many downsides. There is an issue with hyperemia, although for most patients it’s a non-issue or a tolerable one. There are some concerns about eyelash growth, which may be spurred by using a prostaglandin. For some patients that’s a problem, but for others it’s a blessing. There is also the much-discussed prostaglandin-associated orbitopathy. I’ve seen a handful of patients with it, but I’ve never had a single patient complain about it, so I don’t know how significant that is. I put it up there with iris color change. In the 20 years we’ve had prostaglandins, I’ve had two patients who declined to use a prostaglandin on the grounds that it might change their eye color. No patients have ever reported to me that their eye color changed, and I’ve never objectively observed a color change in any patient’s iris.”

Despite prostaglandins’ popularity as a first-line treatment, Dr. Realini says there are a few circumstances in which he might not choose a prostaglandin as the first choice for therapy, such as when a patient has uveitis. “Prostaglandin molecules are important mediators of inflammation, so a prostaglandin might increase the risk of inflammation in someone who is prone to uveitis,” he says. “However, the level of evidence for this is on the order of small case reports and case series, so it’s not a strong association. In fact, I’ve used prostaglandins in patients with uveitis, not as a first choice, but as a last choice before surgery. In that situation I’d much rather take the small risk of aggravating uveitis and give the prostaglandin a try than go to the operating room and take on all of the known risks of surgery.”

Clearly, in order to replace prostaglandin drops as the first-line option for most patients an alternative will have to offer some significant advantages. Treatment options that could conceivably fit the bill—many still in the pipeline—include new drugs; new drops that combine drugs; selective laser trabeculoplasty; and long-term delivery devices. Here, doctors familiar with the latest developments in these areas share their thoughts regarding whether or not one of these options are likely to eventually become the next first-line treatment choice.

|

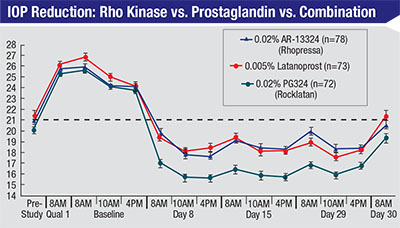

| A recent double-masked, randomized, controlled 28-day study in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension suggests that the Rho kinase inhibitor Rhopressa can be about as effective as latanoprost; combining them may be even more effective.8 |

ROCK Inhibitors

One new class of drugs showing great promise is Rho kinase inhibitors. Savak Teymoorian, MD, MBA, a cataract and glaucoma specialist at Harvard Eye Associates in Laguna Hills, Calif., has participated in the trials of Rhopressa (Aerie Pharmaceuticals), a ROCK inhibitor likely to be the first drug in this class to be approved. “The reason prostaglandins work so well is that they’re dosed once a day, they provide good pressure reduction and the major side effects are all related to the eye, mostly hyperemia issues,” he says. “For any alternative to take over as first-line therapy, it has to be comparable—if not better—in those respects. I think some of the Rho kinase inhibitor products in the pipeline might fit that description, in particular Rhopressa and Roclatan, the latter being a fixed combination of Rhopressa and latanoprost. Both Rhopressa and Roclatan are dosed once a day, and they don’t appear to have any major systemic side effects; just ocular side effects comparable to what we see with the prostaglandins.

“They may provide a couple of other benefits as well,” he continues. “Rhopressa is currently believed to have three mechanisms that lower IOP—via enhancement of the conventional trabecular meshwork pathway; through the reduction of aqueous production; and also through the novel method of decreasing episcleral venous pressure. Notably, all three are different from the mechanism used by prostaglandins: increasing uveoscleral flow. So if you combine Rhopressa and a prostaglandin, you’re lowering pressure through four mechanisms.”

Dr. Teymoorian notes that a ROCK inhibitor has the potential to be an effective tool when treating low-tension glaucoma. “This is one of the hardest types of glaucoma to take care of because the IOP is already low, but you need to get it down even further,” he says. “ROCK inhibitors are relevant here because episcleral venous pressure is a factor in Goldmann’s equation for determining IOP, and none of the current medications really addresses that. The ROCK inhibitors, at least in animal models, have been shown to bring episcleral venous pressure down. Essentially, there’s a certain level of IOP you can’t get below [without creating hypotony] because episcleral venous pressure is always present. No matter how much you reduce aqueous production, or how much you enhance aqueous outflow, you still have to deal with that factor. So in special cases like low-tension glaucoma, ROCK inhibitors may work well, simply because they appear to address that aspect of the pressure equation.

Dr. Teymoorian says another possible advantage of ROCK inhibitors that remains to be confirmed is anti-fibrogenic properties seen in cultures of human trabecular meshwork cells. “There is some evidence that ROCK inhibitors may help to regenerate or rejuvenate a diseased trabecular meshwork,” he says. “That might explain why these drugs appear to increase flow through that pathway.”

Even with these potential selling points, Dr. Realini is skeptical that Rhopressa will become a first-line alternative to PGAs. “The problem is that it doesn’t appear to lower intraocular pressure enough when a patient starts with very high pressure, even though it did a good job if the starting pressure was below the mid-20s,” he says. “This is a perfect example of why we haven’t had a new class of drugs in 20 years. The PGAs set the bar really high. For a new drug to become the preferred first-line agent, it would have to lower IOP significantly more than PGAs to justify the cost of a new branded product over a generic PGA.”

Dr. Teymoorian agrees that the reduced efficacy of Rhopressa when the starting pressure is higher than the mid 20s was one of the important findings to come out of the ROCKET study. “This may be a result of the fact that Rhopressa appears to reduce the episcleral venous pressure,” he explains. “EVP is a constant number, whether the patient’s intraocular pressure is 22 or 42 mmHg, so reducing episcleral venous pressure will have a much smaller impact if the patient’s starting pressure is high. For example, if your IOP is 24 mmHg and your episcleral venous pressure is 8 mmHg, you could theoretically lower the pressure by a third by addressing EVP. If your pressure is 40, the EVP only represents one-fifth of that, so reducing it won’t have as big an impact.

“It’s important to keep the practical side of this in mind,” he adds. “If you look at the Baltimore Eye Study, 80 percent of the glaucoma patients had a pressure lower than 26 mmHg. As a glaucoma specialist, I see this all the time; most of our patients come in with pressures in the upper teens and low 20s. So even though Rhopressa wouldn’t work as well on patients with pressures above 26 mmHg, it could be a valid first-line drug for most of my patients. In addition, it could be a major player in the patients who do have higher pressures, because most eyes above 26 mmHg will need more than one mechanism of therapy. If the patient comes in at 30 mmHg, a 25-percent reduction from a prostaglandin will get you down to 21 or 22 mmHg. Chances are, that’s still too high; you’re going to need an adjunctive therapy. In that case, you might very well end up prescribing both a prostaglandin and a ROCK inhibitor.”

|

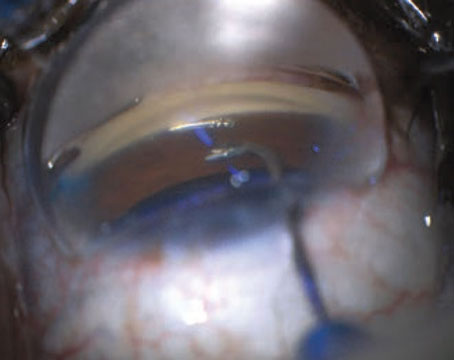

| Sustained-delivery systems are another potential contender for first-line glaucoma treatment. One option under investigation is the bimatoprost ring (ForSight Vision5), which provides sustained delivery of glaucoma medication for six months. It is first placed by the physician under the upper eyelid, then under the lower lid. After placement it is barely visible at the medial edge of the eye. |

Other New Drugs

Other drugs in the pipeline may offer advantages over prostaglandins, although it’s not clear yet whether those advantages will be sufficient to cause them to replace prostaglandins as the first-choice option.

Trabodenoson (Inotek Pharmaceuticals) is a first-in-class selective adenosine mimetic designed to lower IOP by restoring the function of the trabecular meshwork, currently in Phase III development. A Phase II, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled study tested four different dosages of the drug administered twice daily for two or four weeks in subjects with ocular hypertension or primary open-angle glaucoma.1 The drug was well-tolerated, producing no meaningful ocular or systemic side effects. It produced a statistically significant reduction in IOP that increased with greater dosage, and the reduction was significantly greater at day 28 than day 14 (p=0.0163), indicating increasing effect over time. The IOP reduction was also found to be consistent across different patient populations. Evidence from animal studies also suggests that the drug has a neuroprotective effect on retinal cells, but no studies have yet looked for that effect in human eyes.

“I don’t think trabodenoson will outperform a prostaglandin,” says Cadmus Rich, MD, vice president of clinical development at Inotek Pharmaceuticals. “We’re not looking at necessarily being a first-line agent for most patients. However, we have a very good safety profile and clinically significant IOP lowering which I think makes us a good alternative if patients don’t respond to or tolerate a prostaglandin. Our recent Phase II study that was published last month showed a median 4.1-mmHg IOP lowering from baseline, and that was at a lower dose than we’re testing in our current Phase III study. The safety profile in Phase II was very good; we found minimal to no hyperemia and no systemic side effects.

“Trabodenoson produces a clear dose response when you look at the diurnal IOP lowering, and we have not reached an efficacy plateau,” he continues. “For that reason we’re using higher doses in our Phase III study, one that’s twice as high as the dose in Phase II and one that’s three times as high. We feel confident that we may get more pressure reduction than 4.1 mmHg; we just don’t know how much higher.”

Dr. Rich says they are currently testing a fixed combination with latanoprost. “We’re hoping this will provide greater IOP lowering with minimal side effects,” he says. “Unlike the prostaglandins, trabodenoson works at the trabecular meshwork through the conventional outflow pathway, so the mechanism is complementary. We conducted an unfixed combination study; patients on the combination showed very good lowering, and the additional lowering [caused by the addition of trabodenoson] was similar to the amount of lowering seen in trabodenoson monotherapy.” Noting that the Rho kinase drugs offer this potential advantage as well, Dr. Rich points out that trabodenoson has produced minimal hyperemia in studies—less than that seen with Rho kinase drugs. “Hyperemia is already a concern with prostaglandins,” he notes. “Not adding more side effects to the prostaglandin would put us in a different category.”

Another promising drug under investigation is latanoprostene bunod, a novel nitric oxide-donating prostanoid FP receptor agonist. Once inside the eye it’s metabolized into latanoprost acid and butanediol mononitrate, which in turn releases nitric oxide. The nitric oxide causes relaxation of the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal, resulting in increased outflow.

A Phase III, randomized, controlled, double-masked, parallel-group clinical study, involving 387 subjects 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of ocular hypertension or open-angle glaucoma in one or both eyes, compared the diurnal IOP-lowering effect of latanoprostene bunod once every evening to timolol b.i.d. LBN reduced IOP significantly more than timolol throughout the day over three months of treatment; adverse events were similar in both groups.2 Previous studies, including the Phase II VOYAGER study, compared the efficacy of LBN and latanoprost. VOYAGER involved 396 patients with open-angle glaucoma and OH; it showed that reduction in mean diurnal IOP from baseline was significantly greater with LBN than with latanoprost, suggesting the value of the added nitric oxide-donating component.3

New Combination Drops

Adding one or more drops to a first-line prostaglandin is a common way to try to reduce IOP further when the prostaglandin alone isn’t bringing the pressure down to a safe enough level. The drawback, of course, is that this tends to exacerbate the problems associated with adherence. Combining multiple drugs in a single formula minimizes that concern, but so far, no combination drug has come close to deposing prostaglandins from the first-line spot. With new drugs in the pipeline, however, that could change.

Dr. Realini points out that the choice to prescribe a fixed-combination drop as a first-line therapy has become more popular in the past two or three years, but it doesn’t look like this option will replace prostaglandins as the first-line mainstay any time soon. “I do have a few patients who are on fixed combinations as primary therapy, but in most of those cases we started with a PGA and didn’t get a great response,” he says. “What we need is a drug that adds really well to a PGA. None of our current single drugs adds more than 2 to 4 mmHg of pressure reduction when combined with a PGA.”

Dr. Realini notes that fixed-combination drops are doing better as adjuncts to first-line prostaglandins. “Now that generic fixed combinations have started to become available, fixed combinations are becoming much more commonly used as an adjunct to PGAs—they can give you 5 to 8 mmHg of additional IOP reduction,” he says. “But this still means the patient is dealing with two bottles and dosing at least twice a day. The ROCK inhibitors may change that. Preliminary data suggest additivity to PGAs, and a fixed combination [Roclatan] is in clinical trials now. If that works out, the patient could use one drop per day and get a better IOP reduction than with PGA monotherapy. Once a drug lowers pressure 3 or 5 points better than a PGA with once-daily dosing, it’s going to be many people’s first-line choice.”

Dr. Teymoorian agrees. “Naturally, we will run across patients in whom a prostaglandin isn’t sufficient to control pressure,” he says. “In that situation our alternatives would be either to add a second medication or find a better first-line medication. Adding a drug that uses multiple different pathways would be a reasonable option, and if you end up using Rhopressa as a secondary agent and the patient does well, the patient could then be switched to a Roclatan type of product. That would take the patient from two medications once a day back to a single medication once a day, and it would be quadruple-mechanism therapy without any major systemic side effects.”

|

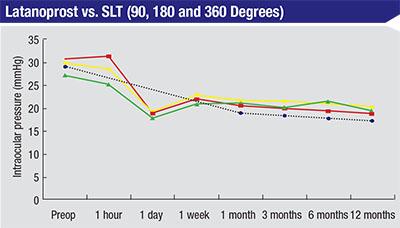

| Selective laser trabeculoplasty is about as effective as a prostaglandin when used as first-line therapy instead of as an adjunct, as demonstrated in this 2005 study.6 (Black line—latanoprost; green—SLT 90 degrees; yellow—SLT 180 degrees; red—SLT 360 degrees.) |

SLT as First-line Therapy

Another candidate for first-line treatment is selective laser trabeculoplasty. Dr. Realini has done extensive work with SLT; he believes its relatively limited use as first-line therapy is the result of some inaccurate popular beliefs. “SLT is at least as safe—and probably safer—than a prostaglandin,” he says. “Plus, it has convenient once-every-year-or-two dosing, as opposed to once-daily dosing. And despite what many people believe, SLT is comparable in efficacy to a prostaglandin when used as a first-line option. Studies in the literature that have compared SLT to a prostaglandin have found them comparable.4-6

“The idea that SLT is less efficacious is perpetuated partly because most surgeons use SLT as their second, third or fourth intervention and find that it doesn’t work as well as a first-line prostaglandin,” he continues. “That’s not a reasonable comparison, because no drug works as well third-line as it does first-line. Consider what happened when latanoprost came on the market. At first, no one knew what to do with it. It had all these weird side effects. So, for the first year after Xalatan launched, it was being used third- or fourth-line. Not surprisingly, people’s perception was that it didn’t work nearly as well as it seemed to work in the studies, where it lowered pressure 7 to 9 points. The reason it worked better in the studies was that it was dosed as first-line monotherapy, not third- or fourth-line therapy. Clinicians were using it in eyes that had already proven themselves difficult to treat because they needed three or four medications.

“That’s exactly where we are now with SLT,” he says. “We just need to get more people trying it first-line. I encourage most of my newly diagnosed patients to consider SLT over prostaglandins as their first therapy.”

Dr. Realini notes that surgeons’ intellectual understanding of the benefits of SLT hasn’t yet translated to a paradigm shift in the clinic. “I’ve been at meetings in a room with hundreds of glaucoma specialists,” he says, “and I’ve asked, ‘How many of you encourage newly diagnosed glaucoma patients to do first-line laser therapy?’ On average, 5 to 8 percent of hands will go up. Then I ask, ‘How many of you, if you developed glaucoma tomorrow, would want SLT first-line?’ Virtually every hand in the room goes up. Why would you take care of your patients differently than you would take care of yourself?

“I think there are several reasons the shift to first-line SLT hasn’t happened yet,” he continues. “If you haven’t thought about how to talk to patients about SLT it becomes awkward. It’s much easier to write a prescription and say, ‘Here, take this,’ than it is to have a conversation about a procedure.” He also notes that the doctor’s perception of SLT’s efficacy will have a huge impact on whether a patient is willing to try it. “You have to believe that it works or you won’t be able to sell it,” he says.

“Many surgeons who offer SLT at the outset say something like, ‘There’s this laser we could try,’ ” he continues. “A patient is not going to find that inviting. On the other hand, you could say something like this: ‘We could try a once-a-day eye drop, but there’s also a laser treatment that’s available. Personally, if I developed glaucoma tomorrow, I’d have the laser tomorrow afternoon. I don’t want to have to remember to put drops in my eye every day and deal with potential side effects, and have to remember to go to the pharmacy every month to get the drops.’ If you present the SLT option that way, most of your patients will say ‘OK, I want the laser, too.’

“Another obstacle is a feeling some doctors have that offering SLT as a first-line treatment isn’t standard,” he says. “If you believe that, then you have to have a longer discussion with the patient and justify what you’re doing. That will never be time-efficient, and you’re not likely to get the patient to agree to have the procedure. You have to believe in your heart that laser is a better first-line option and say so.”

Dr. Realini points out that trying SLT doesn’t reduce the viability of any other options (such as drops) down the road. “Even if SLT only worked as a first-line treatment in half of your patients,” he says, “wouldn’t it be worth trying on everyone so that half of your patients are living a drop-free lifestyle, with no preservatives, no ongoing costs, no adherence issues and no tolerability concerns?”

Extended-release Options

Given that a major drawback of prostaglandin drops is adherence, it seems reasonable that an extended-release modality—whether delivering a prostaglandin or some other drug—might eventually replace prostaglandin drops. However, this type of delivery system is turning out to be difficult to achieve, and it might not be ideal as a first-line choice for most patients even if it works.

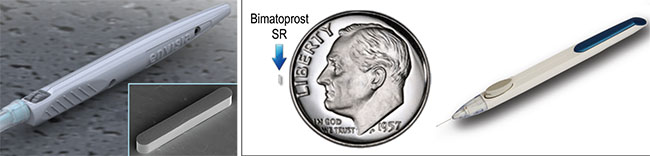

According to Gary D. Novack, PhD, professor of pharmacology and ophthalmology at the School of Medicine at the University of California, Davis, and president of PharmaLogic Development of San Rafael, Calif., which provides development expertise to pharmaceutical and medical device companies, there are at least seven prostaglandin drug delivery systems in clinical development. “Some of these systems apply the drug to the front of the eye via a punctal plug or a scleral ring,” he says. “Some require subconjunctival injection, and some require intracameral injection. The ones on the front of the eye are noninvasive, which is a plus. However, each of those has its own issues. For example, punctal plug delivery systems have to remain in place in order to work, which is hard to guarantee, and the patient has to be able to tell if the plug has fallen out.

|

| Sustained-delivery options under investigation include Envisia’s ENV515 (left) designed to deliver travoprost and reduce pressure for more than six months; and Allergan’s Bimatoprost SR (right) shown with its prefilled, single-use applicator for intracameral administration. |

“There was a sustained-delivery product back in the 1970s called Ocu-sert, a pilocarpine delivery system that was developed by Alza,” he recalls. “That was a good delivery system for pilocarpine, which is very short-acting and effective at lowering IOP. The pilocarpine was cast as a film with alginic acid and then surrounded by an ethylene/vinyl acetate copolymer; it was placed in the lower cul-de-sac where it slowly released the drug, making it last a week. The product was approved and worked especially well for younger patients with accommodation because the pulsatile nature of pilocarpine delivered as a drop resulted in irregular accommodation over the course of the day. That effect had been bothersome to many patients, and this system stabilized that. The downside was that the device could unexpectedly slide across the cornea and obscure visibility. That could be a big problem if the patient happened to be driving at the time, and there were some case reports of that happening. These are the kinds of issues you run into with an external drug source.

“Injected drug delivery options have different issues,” he continues. “We’re more comfortable with intraocular injections these days, but any time you go into the eye there are a number of risks. Also, these systems are not injecting drugs in solution; a solution would dissipate. These involve delivery units that take up space. That means there is the potential for the injected material to occlude part of the angle. Subconjunctival injections might be a happy medium, in terms of the injection risks, because they don’t go inside the eye.”

Dr. Teymoorian is skeptical that patients will accept long-term delivery options that are invasive. “My concern is, if I offer to give the patient an injection, I think people will still opt for eye drops,” he says. “Obviously, we want to eliminate the problem of noncompliance, and an injection would accomplish that. But there are risks you take with an injection that you don’t with an eye drop. If an eye drop doesn’t work, you simply stop using it. If the injection doesn’t work, you have something inside the eye.”

Dr. Novack notes another problem with sustained delivery systems: Not every glaucoma drug will work if delivery is steady rather than pulsatile. “A so-called zero-order delivery system that provides a steady output of a drug might work well for pulsatile drugs like timolol or pilocarpine,” he says. “It’s not clear how well that type of delivery will work with prostaglandins, which are somewhat unique. We know that placing a drop of a prostaglandin twice a day is less effective than doing so once a day. That raises the question as to whether steady-state delivery is the way to go, or whether these drugs need some pulsatility in order to work. We don’t know what the consequences of constant delivery might be. Even with drugs like timolol or brimonidine, steady delivery could conceivably raise the risk of systemic side effects.”

Dr. Realini says he doesn’t see devices that provide sustained drug delivery as a holy grail for glaucoma drug therapy. “First of all, it appears that they are slightly less effective than their eye-drop counterparts,” he says. “It turns out that if you constantly flood the eye with drug molecules, the receptors appear to downregulate over time; they become a little desensitized. In contrast, in daily therapy you put a drop in the eye and it binds to the receptor; then the receptor goes for hours without seeing any more drug, so there’s no reason for it to become sensitized. It has a downtime recovery period between doses. Admittedly, the difference in effect is very small, probably on the order of a millimeter of mercury or so, and the long-term benefits of a sustained-release option—such as reduction in exposure to preservatives, assurance that the patient isn’t missing doses and better overall circadian coverage—probably outweigh that.

“However, another question is, when would these devices be used?” he continues. “Suppose Mrs. Johnson has been taking a prostaglandin every day for the past 20 years and she’s doing really well. Why would you switch to something invasive and more expensive? And why would her insurance company pay for that? That’s the situation most of our patients are in. And if you have a patient who is not doing well and is getting worse, the only way in which sustained delivery could possibly improve that situation is if you are absolutely convinced that adherence is the reason the patient is getting worse. And how are you going to prove that?

“So I don’t know where those things will fit in,” he says. “Everyone says, ‘Look at macular degeneration. The patients tolerate monthly injections and the insurance companies pay for it.’ But would they pay for it if there was a topical anti-VEGF drop that patients could take every day? It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison.”

Dr. Novack says he doesn’t believe we have enough data yet to say too much about the efficacy and safety of these devices. “So far, we’ve only seen Phase II data on a few of these products, and of those, only three have shown ocular hypotensive efficacy similar to what you might expect from a daily drop of prostaglandin,” he says. “To date, no delivery system has produced greater IOP lowering that you would achieve with a drop, and some have been less effective. So, given the data we have right now, it appears that these options will be primarily for patients with financial or capability limitations.”

Dr. Novack also wonders whether the American health-care system will be able to cover the cost of these devices. “We’re talking about paying the cost of compensating for poor patient adherence and performance,” he says. “Along with the problem of patients not always wanting or remembering to take their drugs at the right time—and continuing to do that for the rest of their lives—we also know that people have difficulty getting the drops onto their eyes. I coauthored a paper with Alan Robin, MD, showing that only one-third of experienced glaucoma patients could put in a drop correctly.7 If we can solve this using a new delivery system that’s priced at a premium, will the health-care system pay for it? We don’t know.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Novack believes a sustained-delivery system could become a first-line option for certain patients. “There are some patients for whom eye drops don’t work,” he says. “Some patients clearly can’t adhere to a treatment protocol or get the drops onto their eye. It’s possible that a drug delivery system could be a first-line treatment for that kind of patient. And whether or not they become a first-line treatment option, they will serve a crucial purpose. Years ago I worked in the contraceptive field. We used to argue that abstinence is 100-percent effective; the problem is, its ‘real-use’ effectiveness isn’t that great. You may have the greatest drug in the world, but if the patient doesn’t take it won’t be very effective. So you could argue that some of these delivery systems will offer patients real effectiveness. That’s not a small thing.” REVIEW

Dr. Realini is a consultant to Alcon, B+L, Valeant and Inotek; he receives research support from Alcon, Topcon and OptoVue and is on the speaker’s bureau for Lumenis. Dr. Novack has worked with more than 300 companies, including Aerie Pharmaceuticals and B+L, to develop products. Dr. Teymoorian is a researcher and consultant for Aerie.

1. Myers JS, Sall KN, DuBiner H, Slomowitz N, McVicar W, Rich CC, Baumgartner RA. A dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of 2 and 4 weeks of twice-daily ocular trabodenoson in adults with ocular hypertension or primary open-angle glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2016 Mar 22. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Robert N. Weinreb RN, Sforzolini BS, Vittitow J, Liebmann J. Latanoprostene bunod 0.024% versus timolol maleate 0.5% in subjects with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: The APOLLO study. Ophthalmol 2016:123;5;965-73.

3. Weinreb RN, Ong T, Scassellati Sforzolini B, et al. A randomised, controlled comparison of latanoprostene bunod and latanoprost 0.005% in the treatment of ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma: The VOYAGER study. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:738–745.

4. McIlraith I, Strasfeld M, Colev G, Hutnik CM. Selective laser trabeculoplasty as initial and adjunctive treatment for open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2006;15:2:124-30.

5. Katz LJ, Steinmann WC, Kabir A, Molineaux J, Wizov SS, Marcellino G; SLT/Med Study Group. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus medical therapy as initial treatment of glaucoma: A prospective, randomized trial. J Glaucoma 2012;21:7:460-8.

6. Nagar M, Ogunyomade A, O’Brart DPS, Howes F, Marshall J. A randomised, prospective study comparing selective laser trabeculoplasty with latanoprost for the control of intraocular pressure in ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:11:1413–1417.

7. Stone JL, Robin AL, Novack GD, Covert DW, Cagle GD. An objective evaluation of eyedrop instillation in patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:6:732-6.

8. Lewis RA, Levy B, Ramirez N, C Kopczynski C, Usner DW, Novack GD; PG324-CS201 Study Group. Fixed-dose combination of AR-13324 and latanoprost: A double-masked, 28-day, randomised, controlled study in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:3:339-44. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306778. Epub 2015 Jul 24.