As you know, the challenges are many when you’re confronted by a hard, intractable and leathery cataract that’s difficult to disassemble. High on the list of difficulties, of course, are the potentially perilous use of phacoemulsification, predisposition of the posterior capsule to rupture and the possibility of a traumatized corneal endothelium.

Surgeons at the Dr. Om Parkash Eye Institute in Amritsar, Punjab, India, routinely take on these cases by employing what they describe as a chopper scaffold technique, effectively removing the cataract while sparing the eye unnecessary damage. By reading this review of their approach, you can decide if you want to include it in your surgical arsenal and, if so, how you can implement it.

Familiar Consequences

Like you, Rohit Om Parkash, MS, head of the department of cataract services and chairman of the Institute, is all too familiar with the potential unwanted consequences of not breaking up a hard cataract effectively and struggling through even a good procedure to ensure a trouble-free extraction with as little disruption as possible. That’s why his team has developed a technique that responds to the specific challenges of difficult phacoemulsification and potential corneal endothelium trauma.

|

“We know that increased ultrasound usage causes endothelial cell loss because of mechanical and thermal injury from ultrasonic waves emanating from the ultrasonic tip,” he notes. “In addition, we also see mechanical trauma caused by nuclear fragments and instrumentation. In hard cataracts, we must also respond to an environment of high fluidics. The hard fragments of the cataract are irregularly-shaped and rigid. It’s important to remember that these pieces don’t mold suitably at the phaco tip. As a result, we see uncontrolled scatterings of fragments, causing damage to the corneal endothelium in these cases.”

In concert with these effects are related risk factors that predispose the patient with a hard cataract to posterior capsule rupture because of zonular weakness, he adds. “The zonular weakness makes the bag floppy,” he points out. “The use of high fluidics, in turn, predisposes the eye to post-occlusion surge. At times, those sharp nuclear fragments can cause collateral damage to the posterior capsule.”

In this environment, adds Tushya Om Parkash, MS, director of the cataract and refractive department at the Institute, instrumentation that you can normally use quite safely poses a risk

“The use of blunt instruments, unintended insertion of instruments between the corneal stroma, Descemet’s membrane, improper incisions and tight main incisions can all cause damage in these cases,” says Dr. Tushya Om Parkash. “Damage to Descemet’s membrane during irrigation and aspiration and during insertion of an IOL or phaco probe can also occur. These problems, along with the potential inexperience of a surgeon, are but a few of the intraoperative risk factors.”

Standard Remedies

Shruti Mahajan, MS, a member of the practice at the Institute, notes that applying current concepts in practice that minimize the risks of ultrasound usage in a hard cataract are important to keep in mind.

“These include direct phaco chop and the use of power modulations and torsional settings (in which the phaco tip oscillates in a rotational manner along its primary axis) that use a variable pulse and burst mode,” says Dr. Mahajan. “Another big help when removing hard cataracts is the use of phaco tips with decreased amplitude near the incision.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Rohit Om Parkash emphasizes the need to focus your efforts on minimizing mechanical endothelial trauma at all times. He recommends employing the following approaches:

• use of endocapsular or deeper- plane phacoemulsification of totally separated small nuclear fragments;

• hypothermic perfusion;

• fluidics to provide a stable anterior chamber;

• use of an anterior chamber maintainer;

• replenishment of the anterior chamber with a visco-dispersive device; and

• relying on a femtosecond laser or manual pre-chopping techniques.

To address predisposition to endothelial trauma, he remains ever mindful of the reckless nature of those nuclear fragments, which all too often defy attempts to use the phaco tip carefully.

“Despite the energy modulations you may use, it’s important to be constantly vigilant, mindful that the rigid and irregular nuclear fragments won’t mold well at the phaco tip,” he repeats. “Normally, of course, the nuclear pieces, with the use of fluidics, mold well with the phaco tip and are aspirated. We become accustomed to this. But when the nuclear pieces don’t get aspirated, they can quickly get pushed off of the phaco tip by the ultrasonic power of the phaco unit, creating chatter and poor followability. This activity results in sharp nuclear fragments bouncing off of the tip in an uncontrolled way and hitting the corneal endothelium, resulting in significant endothelial cell loss.”

Dr. Rohit Om Parkash notes that in cases of an increased anteroposterior diameter of the nucleus and a shallow anterior chamber, the working space in the anterior chamber poses an additional challenge for the surgeon. “This can increase the risks of chatter-related endothelial injury,” he says. “Sometimes a misdirected stream of fluid can also predispose Descemet’s membrane to detachment. Yes, dispersive OVD helps in shielding endothelial cells. However, the shield is temporary and there can still be endothelial injury.”

|

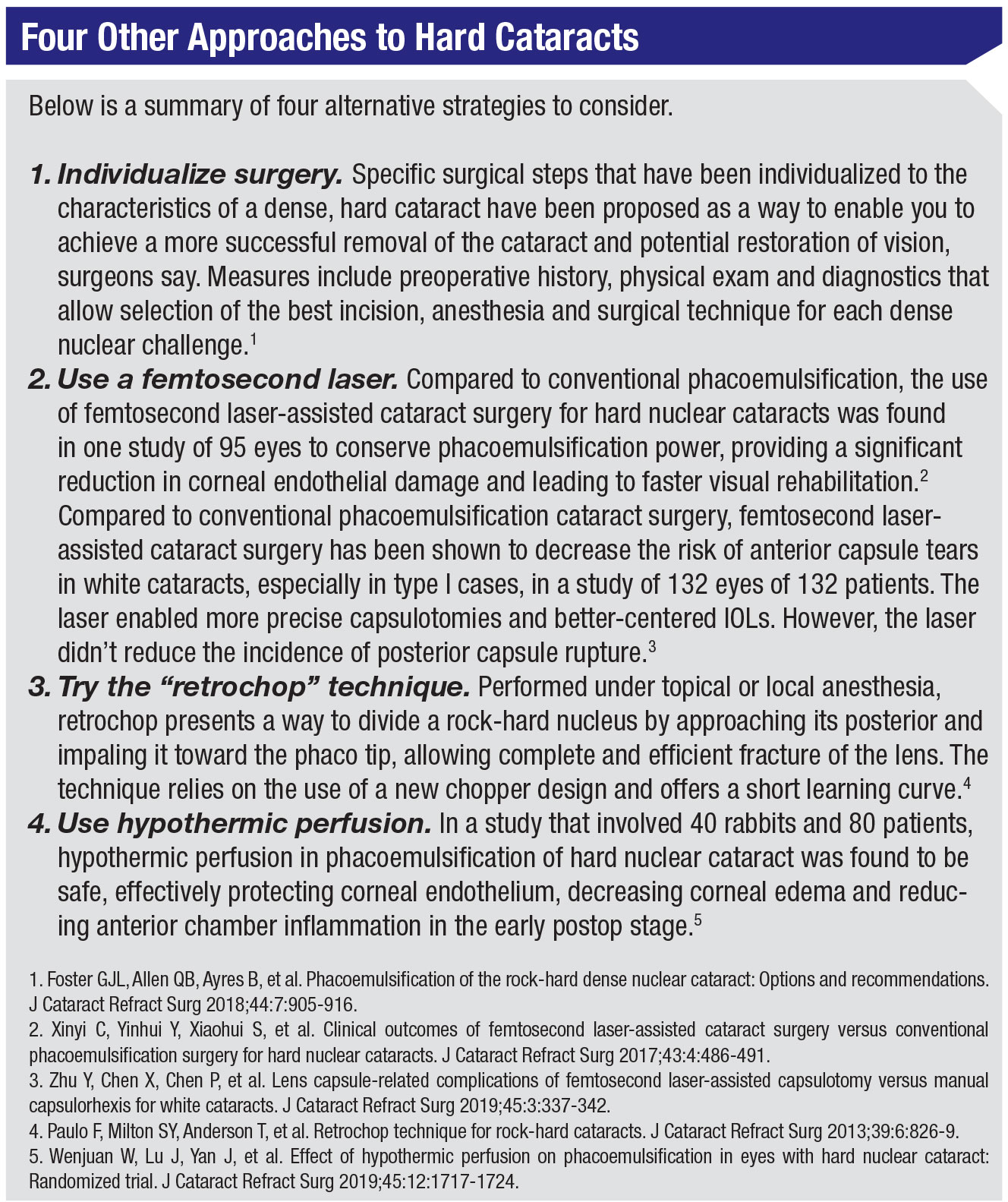

The Chopper Scaffold

When they developed the chopper scaffold technique, the senior Om Parkash says the goal of his team members was to use a common chopper as an alternative to dispersive OVD. They rely on the chopper, not dispersive OVD, to shield the corneal endothelium. “The positioning of the chopper must be between the phaco tip and the corneal endothelium when you’re using this technique,” he explains. “The shaft of the chopper, along with the phaco tip, mechanically shield the corneal endothelium from the chattering of the hard and pointed nuclear fragments. Our simple technique is easy to adopt, and it results in pristine clear corneas on postop day one. It requires neither a longer surgical time, with different phaco parameters, nor unique surgical preparations.”

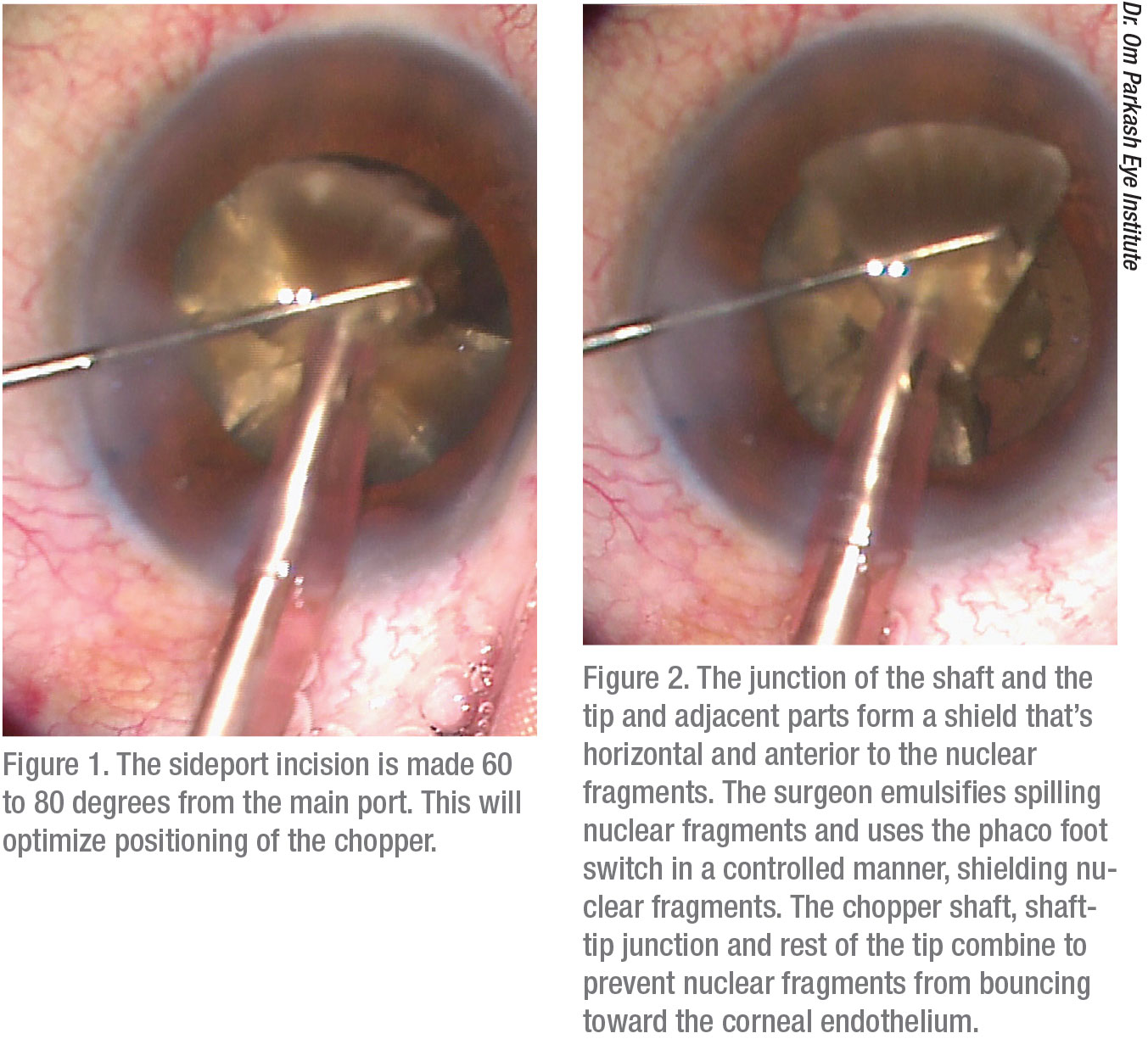

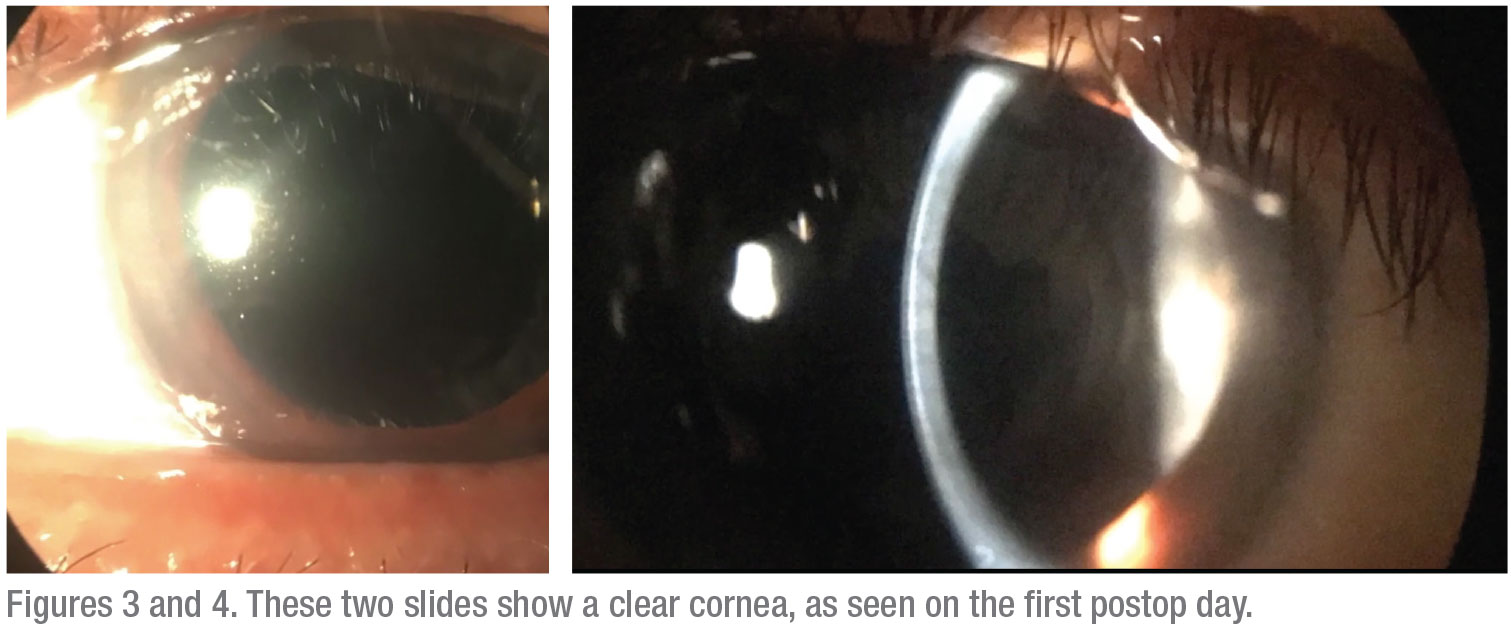

Dr. Tushya Om Parkash describes the technique in more detail. “You begin by making a sideport incision 60 to 80 degrees away from the main port,” he says. “This facilitates ideal positioning of the chopper. Part of the chopper forms a junction with the tip of the phacoemulsification probe. Parts of the chopper and the phaco tip are primarily used to form a shield by horizontally placing the parts in a position that’s anterior to the nuclear fragments.”

While applying the technique, he says you will need to demulsify the spilling nuclear fragments. The foot pedal needs to be used in a controlled way as you shadow (shield) the fragments with the chopper shaft, the shaft-tip junction and the rest of of the tip, preventing the fragments from bouncing toward the corneal endothelium.”

He also recommends the use of a thin chopper, which won’t obscure your view of the surgical field. Otherwise, he continues, “you don’t need to select any specific type of chopper. The routine chopper that you use will suffice. You also don’t have to be concerned about overcoming any learning curve when adopting this technique. You just need to be careful to shadow (shield) the nuclear fragments around the phaco tip by placing the chopper in a near horizontal plane. You should be able to easily incorporate this technique into your surgical routine without any fuss.

“Our initial experience has yielded very clear corneas in the immediate postop period and acceptable levels of endothelial cell loss,” Dr. Tushya Om Parkash adds. “The results of a study we performed reveal a significant benefit for the surgeon and the patient compared to the results we might have seen if we hadn’t used this technique in these hard cataract cases. The levels of endothelial cell loss when using our phaco-based chopper scaffold approach are comparable to the low levels seen in femtosecond-laser-assisted cataract surgery.”

To view a video of the chopper scaffold technique that these doctors presented at the ASCRS Virtual Annual Meeting on May 16, you can click on the following link and search for “Chopper Scaffold Technique” in the CME section: ascrsvirtualmeeting.ascrs.org

(Make sure you have a username and badge number for the virtual meeting.)

|

Testing the Technique

To validate the success they achieved in a few patients when using the chopper scaffold technique, the surgeons at Dr. Om Parkash’s practice conducted a one-year study (referenced earlier). Two prototypes of phaco choppers were used, including a sharp tip for chopping and a blunt tip for providing a scaffold while they performed phacoemulsification. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of the chopper scaffold technique as a means to reduce to reduce endothelial cell damage and postop corneal edema when removing hard cataracts.

The randomized, prospective study involved 35 eyes of 30 patients who underwent phacoemulsification between July 2018 and June 2019. Inclusion criteria permitted the use of eyes with nuclear sclerosis grade >4 and an anterior chamber depth >2 mm. Central corneal thickness and endothelial cell count constituted the studied parameters.

Alcon’s Centurion phacoemulsification system was used for the surgery, employing a balanced tip and power at 75 percent in the longitudinal mode, vacuum set at 650 mmHg and an aspiration flow rate of 42 cc/minute for the chopping maneuvers.

After the chopping maneuvers, individual fragments were mobilized out of the bag and emulsified at the pupillary plane, using 90-percent power in torsional mode with 600 mmHg of vacuum and an aspiration flow rate of 50 cc/min.

Study Results

Following their year-long study, the surgeons tabulated the findings and found that the mean endothelial cell loss after three months was about 6 percent, which was within normal limits, decreasing from 2,246.2 ±193.55 preop to 2,106.77 ±185.54 postop. All of the postop eyes had clear corneas on the first postop day. The mean central corneal thickness increased to about 6 percent of its preop thickness the day after surgery (rising from 527.93 ±22.09 µm to 560.43 ±23.22 µm) but this measurement dipped to the preop values at the end of day seven.

In conclusion, the surgeons believe they have established a simple technique that can be adapted by their peers. “Quite simply, it can help preserve the corneal endothelium better,” says Dr. Tushya Om Parkash. “Along with power modulations and modified nuclear disassembly techniques, this approach will help surgeons make phacoemulsification in rock hard cataracts much safer.” REVIEW

Doctors Tushya Om Parkash, Rohit Om Parkash and Mahajan report no relevant financial disclosures.