Phacoemulsification may be the mainstream approach to cataract surgery across much of the world, however, the presentation of advanced, hyper-dense lenses requires special consideration. Using phaco in these patients comes with risks, including trauma to the endothelium and surrounding structures, say surgeons. Developing familiarity with techniques such as manual small-incision cataract surgery (MSICS) and tools like the miLoop fragmentation device (Zeiss) can prepare surgeons for these scenarios while making the procedure safer for patients. However, it’s not something one can learn overnight, and we spoke with surgeons who advocate for these alternatives in certain cases, but also emphasize the importance of proper training. For those who invest the time, these techniques could be a differentiating component of your practice.

MSICS Candidates

|

|

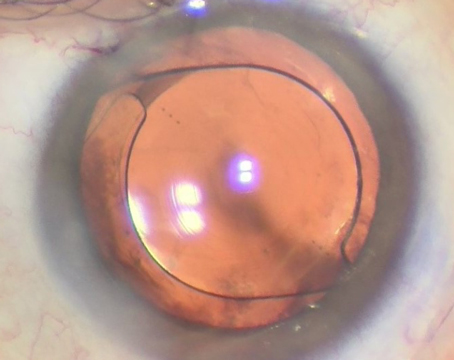

Manual small-incision cataract surgery involves creating a scleral tunnel (A) from which the entire cataract can be removed in one piece (B). Some surgeons say the scleral tunnel can be the most difficult aspect of MSICS to learn. |

MSICS was designed to address hyper-dense cataracts where phacoemulsification is too risky, or in cases where surgeons don’t have access to a phaco machine due to economics, which is why MSICS is commonly used in lower-income and developing countries. Many of these regions are facing a high-volume of patients, and MSICS provides a high-quality, sutureless surgery with a self-sealing tunnel.1

Although MSICS may be a natural solution for surgeons in some low- and middle-income countries, for example, it has its place in Western ORs as well. “We may be discussing MSICS in the setting of hyper-dense cataracts, but the technique that’s learned with creating these large-diameter scleral tunnels ends up being exquisitely useful to our surgeons in a variety of other situations, such as cases of zonulopathy or in those who have pre-existing endothelial dysfuntion—Fuchs’ dystrophy being the most common,” says Brenton D. Finklea, MD, a surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia and director of its Center for Academic Global Ophthalmology. “An additional benefit to MSICS is in the setting of completely mobile cataracts. In severe zonulopathy such as with trauma, the cataractous lens may be dislocated into the anterior chamber making phacoemulsification nearly impossible. Taking these cataracts out by way of an intracapsular approach through a large-diameter scleral tunnel may be the least traumatic approach. The same is true of explanting dislocated PMMA lenses from previous cataract surgeries. The MSICS-style scleral tunnel can be a skill that will really save the day.”

Jeff Pettey, MD, the vice-chair of clinical affairs at Moran Eye Center and an associate professor at the University of Utah Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, says MSICS doesn’t rely on fluidics to form the chamber in the same way that phaco does. “As such, you’re doing the surgery at relatively low pressures inside the eye so you don’t have that extra stress of pressure down into the posterior chamber from a high IOP or a high bottle height, and in a loose zonules case, that can be very well-controlled with MSICS,” he says.

MSICS may have particular benefit for reducing the risk of loss of lens fragments into the posterior segment should capsular disruption occur, Dr. Finklea says. “The way that the hydrodynamics work for phacoemulsification is you have a highly pressurized anterior chamber relative to a low-pressure posterior chamber, ” he explains. “If there’s any disruption in that capsule diaphragm, the pressure gradient is going to push lens material from the anterior segment into the posterior segment—you’re going to lose a lens that way. In MSICS you have the reverse situation, where you have a higher standing pressure in the posterior segment than you do in the anterior segment, where the pressure is functionally zero once you’ve opened your main incision. If you do have a disruption of the lens capsule, it’s very uncommon for the lens to move posterior unless the patient has had a prior vitrectomy. In low-resource settings where you may not have access to pars plana vitrectomy and lensectomy, MSICS may confer an overall lower risk of losing nuclear material into the posterior segment. Even when full access to surgical care is available, MSICS may be the best choice if you think there’s a high risk for loss of lens or capsular support.”

Dr. Pettey says MSICS is also useful in significant corneal opacity. “If you have real difficulty seeing the anterior capsule, whether or not you’ve been able to perfectly complete the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, which is essentially a requisite for phaco,” he says. “In contrast, in MSICS, other capsulotomy methods don’t rely on that same level of visualization through the cornea, and you can still have an excellent outcome removing the lens.”

MSICS Techniques

Employing and succeeding with MSICS comes down to training, say surgeons. “MSICS has much faster visual recovery for dense lenses,” says Dr. Pettey. “This has been shown over and over in multiple studies. Ultimately, the result of MSICS vs. phaco can be relatively equivalent in the surgeon’s hands, depending on their skill set. In many ways, it depends on the surgeon and their comfort level and skill with each technique.”

Dr. Pettey, like most surgeons in the United States, only trained in phaco initially, but now has skill in both techniques. “Depending on how someone trained, if they trained primarily in phaco and never trained to do any extracap or MSICS, then they’re always going to do phaco,” he says. “In contrast, partners worldwide who trained primarily in MSICS and never really trained in phaco will do MSICS for their cases. For those of us with dual skills, it depends on our comfort level. I trained entirely in phaco and MSICS later while working around the world, so for me, phaco is still the most comfortable. However, there are certain cases, such as extremely dense hard lenses, where doing phaco will give me a worse outcome than if I can do MSICS.”

|

|

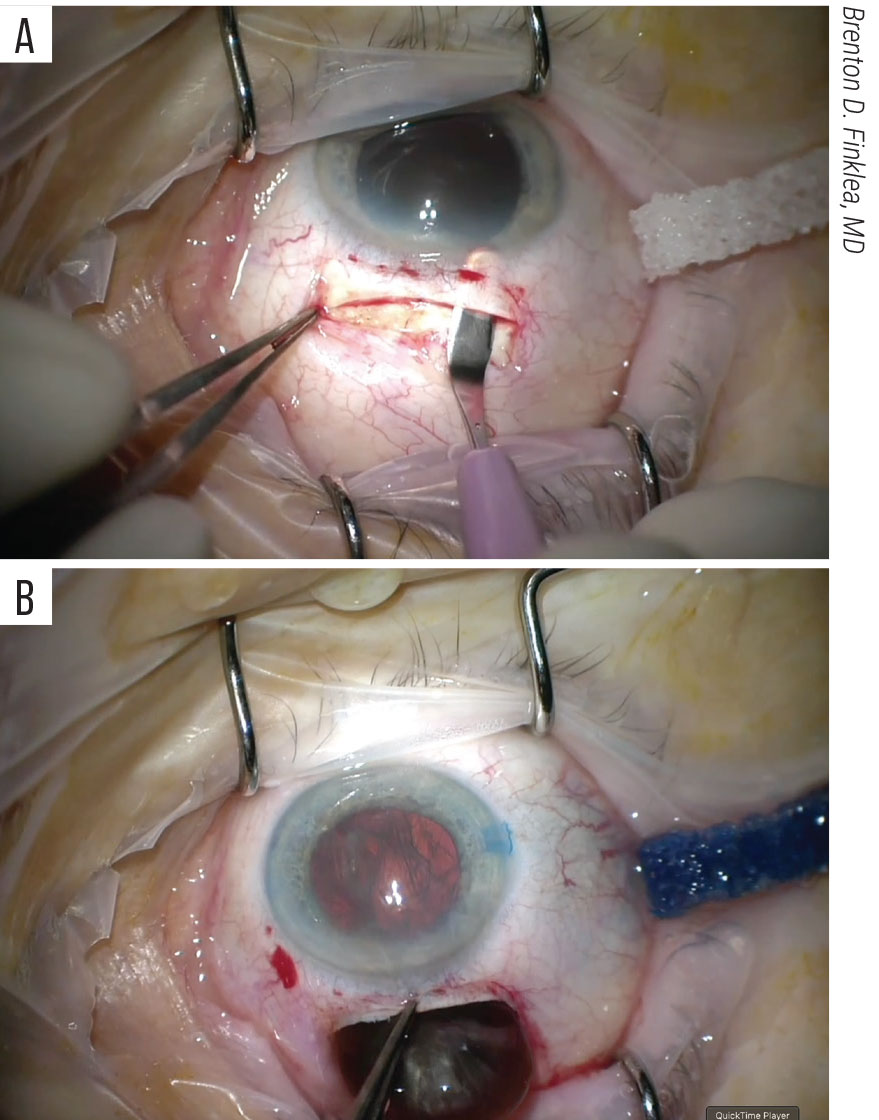

The miLoop is a phaco-sparing device that can be used to break up a dense cataract. |

The biggest difference between phacoemulsification, and subsequently the greatest hurdle to learning MSICS, is creating the scleral tunnel. “Tunneling isn’t commonly taught in U.S. residency programs, and it is a bit of a dying art,” says Dr. Finklea. “If you didn’t train 20 years ago or beyond, it’s unlikely that scleral tunnels were a significant component of your surgical training. That’s something we’ve tried to emphasize as part of the Wills resident curriculum, so that our trainees graduate with wetlab experience and a handful of surgical cases to introduce them to these techniques.”

But once surgeons can master the self-sealing scleral tunnel, they’ll realize that the rest of the steps in MSICS are similar to phaco. “For a competent phaco surgeon, the key is the self-sealing tunnel,” Dr. Pettey says. “With a well-constructed wound, they can do a nice MSICS using their existing skill set. They could do a large CCC, hydro-express the lens into the anterior chamber during hydrodissection, and then use a lens loop to extract the lens. They could then use bimanual I/A to remove all of the cortex. The reason you’re using bimanual is because that large self-sealing wound really does cause an unstable chamber during cortical removal or viscoelastic removal. At that point, you put in your lens, and if that wound is self-sealing, you’re done with the surgery after you clear up the viscoelastic.”

Dr. Finklea says his technique is fairly standard and is the one Wills has determined to be most teachable. “I try to maintain a style of surgery that’s easily transferable,” he says. “That being said, there are a few changes which have been made to modernize the procedure as much as possible. Of course, we try to minimize the diameter of our scleral tunnel to keep the surgically induced astigmatism to a minimum. Frown-shaped incisions and longer tunnels can aid in this as well. Additionally, at the end of every surgery I put a single compression suture into the scleral tunnel in order to further reduce the against-the-rule astigmatism that’s common with superior-approach MSICS.”

Counteracting astigmatism is something Dr. Finklea takes into consideration when positioning his body in the OR. “I always review topographies prior to surgery, and attempt to operate on axis. For example, if the patient has 2 D of against-the-rule astigmatism, I’ll usually operate from a temporal approach to try and induce with-the-rule astigmatism to cancel that out,” he says. “A more purposeful approach to minimizing astigmatism is one of the changes that we’ve made.”

Most of the literature on MSICS includes different techniques for anterior capsulotomies, although the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis is usually preferred, says Dr. Finklea. “We really try to maintain a continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis just to make sure that we’re centering our lenses as consistently as possible and that we’re not having any unexpected tear outs,” he says.

Phaco surgeons may even find themselves in the situation where converting to MSICS might be for the best—if they know how. “We’ve all been in situations where we get into a lens with phaco and realize that it doesn’t end well for the eye because the lens is too dense,” Dr. Pettey says. “If you have a phaco incision made, which occurs the vast majority of the time, creating that self-sealing scleral tunnel can be challenging if you’re doing that through the phaco wound. If you do MSICS conversion after making a phaco incision, then you need to rotate 90 degrees to the superior approach.

“One thing that you could do if you’re concerned or questioning whether or not you’ll need to convert is to do your initial capsulotomy through a paracentesis so you don’t create a phaco incision,” he continues. “Those steps would be: make your paracentesis incision, inject lidocaine with epinephrine, viscoelastic and then insert a micro utrata through your paracentesis. Create your large capsulorhexis and then test the lens through that paracentesis to see how dense it is and how likely it will be able to be done by phaco or MSICS. At that point, if you’ve decided it’s phaco-able, you make your temporal incision and continue with phaco, and if you choose to use MSICS, you make your SICS incision and proceed. It’s not so much a planned conversion, it’s about keeping all options on the table.”

U.S. surgeons who want to learn MSICS are at a bit of a disadvantage because there’s not a high volume of candidates. “As a phaco surgeon, you may have one a month that might be a good candidate, but only doing one a month isn’t enough volume for you to develop muscle memory and consistency in most circumstances for a brand-new technique,” explains Dr. Pettey. He says the best pathway to learning MSICS is the following:

- familiarize yourself with textbooks and videos;

- find a mentor that you can do the surgeries with; and

- do enough cases in a short time frame where you can develop a lot of the muscle memory required for consistency and safe surgery.

Wet labs and model eyes are options to consider, continues Dr. Pettey. “Pig eyes are perfect for learning a scleral tunnel,” he says. “They’re an ideal surrogate, and people can gain mastery of the scleral tunnel on their own doing pig eye wet labs; contact your local academic program. There are available simulators. Suppose you want to use model eyes, such as Bioniko, which has an MSICS simulator. And as far as I know, there’s an MSICS simulator in the Kitaro. Both models are helpful for learning the mobilization of the lens inside the eye and removing the lens, but they aren’t suitable for scleral tunnels.”

Where miLoop Fits In

When MSICS comes up in conversation, the miLoop device is often mentioned along with it because it’s also phaco-sparing for dense lenses.

According to Kira Manusis, MD, who is a cornea and cataract specialist at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, the device was created by a colleague, Sean Ianchulev, MD. “He was in Italy and he was watching them slice hard cheese with a wire,” she recalls. “He thought, what if, in these super dense lenses you could just slice them? The key with miLoop is a very thin nitinol filament. You open the filament in the eye and you rotate the loop around the lens and close it to essentially slice that lens in half just like you would slice cheese.”

She says the fact that miLoop slices from the outside in is key because of the posterior plate. “Even the most amazing surgeon in the world, when we either chop or use any type of fragmentation technique—a femtosecond laser, phaco chop or divide and conquer—we usually do it from the inside out,” Dr. Manusis continues. “We try to be very careful when it comes to getting close to the posterior capsule so we don’t break it and that’s where that posterior plate is. It’s usually thick and it’s very hard to separate the pieces to debulk the lens. There’s really very little you can do other than chopping into smaller and smaller pieces. You just have to take your time and be diligent to do that in order to preserve the capsule. But that posterior plate is very hard to break and what miLoop does is it actually goes behind that plate and slices from outside in. That’s really huge in some of these cases because the most challenging things are to fragment the lens and break up that posterior plate.”

The miLoop is a single-use device and can be operated with one hand. The handle contains a slide bar which opens and closes the ring. Dr. Manusis says it’s important to open and close the device as a test just once before putting it into the eye. “The latest versions of miLoop only allow you to open and close it three times total and then it locks itself,” she advises.

|

|

The miLoop can be operated with one hand and features a slide bar for opening and closing the nitinol ring. Surgeons say it’s important to practice this technique on normal cataracts to become comfortable, and to avoid using miLoop in cases with zonulopathy. |

“Once you see that it’s working, close it and insert it sideways through your main incision and hold your finger on the button that actually allows you to open and close the miLoop,” explains Dr. Manusis. “Once the miLoop is in the lens plane being held sideways, you start to open it so it’s facing to the right—it should always be to the right, this is the only way it opens up. You want that loop to go under your anterior capsule. Ideally you want a well-dilated pupil and a large capsulorhexis. You definitely want to have a good hydrodissection to make sure the lens is mobile, and what I do sometimes is put a little viscoelastic under the anterior capsule, especially in the area where miLoop is going to enter to make it a little smoother and easier for you to visualize. Then, start opening miLoop slowly and you watch it go under your anterior capsule and then disappear under your iris and you want to open it to your right. the miLoop has to stay centered.”

One of the biggest mistakes Dr. Pettey sees with miLoop is people pushing it too far into the eye. “The original miLoop had a mark that you would put into the limbus; the new miLoop doesn’t have a mark but has a little cushion that helps you know when you’re in far enough,” he says. “The challenge is that anatomy isn’t all the same. In the early cases, most learners will push the miLoop too far inside of the eye rather than keeping that injector proximal toward the wound.”

Once the miLoop is open, you want to stay centered and start rotating clockwise, says Dr. Manusis. “Surgeons should be able to see the wire moving below the lens if it’s not too dense,” she continues. “Turn it 90 degrees to encircle the lens completely. If you can’t see because the lens is so dense you’ll know by the position of your fingers in relation to the loop. When I’m ready to close the loop, I usually put my second instrument into the eye to help stabilize the lens as I’m closing. Generally, it will slice it just like it would slice cheese or slice butter. It should go through it very, very nicely. If I slice it into halves, sometimes I’ll push one half back into the bag with my second instrument and leave the second half prolapsed up so I can go in and chop it further or phaco it, whichever. Some people use that second instrument to push the lens back into the bag to make sure that it stays in the bag. After slicing it once, you can use your second instrument to rotate 90 degrees and slice it one more time into quadrants. All of that’s done without the use of any energy because MiLoop doesn’t require any energy. Once you slice it the second time you can use that second instrument to help keep the pieces in the bag or help get one of these quadrants out of the bag to make it easier for you to start phaco.”

Dr. Manusis says using miLoop is relatively quick compared to the amount of time it would take to phaco a hyper-dense cataract.

There are concerns with miLoop’s use in the event of zonulopathy. “If I think the lens is so dense and the chamber is so shallow where, even with the use of miLoop, there may be significant trauma to the endothelium, MSICS is a little bit more gentle because you’re not using any phaco,” she says. “Also, if you have a super shallow chamber and there’s very little room in the eye, sometimes it’s difficult to insert miLoop and get it chopped just because of anatomy, so in that case we may want to do MSICS.”

Dr. Finklea also has a few reservations with the device and says surgeons shouldn’t just grab for it without practicing in a wetlab setting or on routine cases. “It’s a really nice technology that at least reduces one of the potential risk points in phacoemulsification which is simply dividing the lens into fragments in the setting of a leathery posterior plate,” he says. “My biggest qualm with it is the potential for zonular strain, which can be minimized but not completely avoided. Many of these severely advanced cataracts also have comorbid zonulopathy and occasionally miLoop-assisted lens fragmentation can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. If miLoop is something that you plan to use on a regular basis, then master the tool in a controlled setting before employing it on the most challenging eyes. ”

Dr. Manusis instructs residents to try miLoop on routine cataracts first to get comfortable with the instrument before using it on denser lenses. “Every time you use it you get more experience and you get more comfortable,” she says. “One pearl that I’ve learned for myself is when I do my capsulorhexis to try to see how good the zonules are. I definitely don’t use miLoop in cases that have significant zonulopathy because, in my hands, just the sweep of that loop can sometimes tug on the zonules.”

Skills Trump Technique

In the end there’s not one technique that’s the best for all situations, it’s going to be whatever the best technique is in a particular surgeon’s hands, says Dr. Finklea. “If you decide that you’re going to begin offering MSICS surgery, you will need to make a significant time investment in acquiring the skill set. Wetlabs and surgical mentorship will set the stage for a successful transition into this technique. For many phaco surgeons, it may not be feasible to invest the time and resources into becoming fully proficient in MSICS. These individuals will best be served by endeavoring in the most up-to-date phaco equipment and techniques to tackle these most challenging of cases.”

Dr. Finklea and Dr. Manusis have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Pettey consults for Zeiss.

1. Gurnani B, Kaur K. Manual Small Incision Cataract Surgery. Stat Pearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing 2023.