In the realm of refractive surgery, much of the conversation and research is centered on correcting myopia, largely due to its epidemic-like prevalence in the general population. Recent statistics estimate that myopia affects approximately 40 percent of the population in the United States, while only about 10 percent have hyperopia.1-2 Refractive surgeons may also be hesitant to treat hyperopes—at least surgically—because of the anatomical variations inherent to these eyes, including short axial length, a small anterior segment and a higher incidence of angle closure glaucoma,3 which make them prone to regression and unpredictability.4

In spite of these challenges—and with managed patient expectations—hyperopes are able to receive treatment with corneal refractive surgery or intraocular procedures such as refractive lens exchange. We spoke with a few surgeons about how they approach these candidates and the variables that influence their decision.

Hyperopia’s Challenges

Hyperopes commonly accommodate naturally early on in their life and it’s not until mid-life that they become bothered by it.

“Patients who are presenting for hyperopia are typically entering the presbyopic phase of life, or they have latent hyperopia,” says Jennifer Loh, MD, a comprehensive ophthalmologist who practices in South Florida. “Often, when they were in their 20s and 30s, they didn’t need glasses. As they start entering their 40s and get into the presbyopic phase, they start losing that accommodative ability, which at first affects their near—which they work through—but then it starts to affect distance because the hyperopia keeps getting stronger and their accommodative amplitude is decreasing.”

Thomas M. Harvey, MD, a refractive surgeon with a practice in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, calls hyperopia a “challenging refractive status.” “Hyperopic patients often show up in our laser centers asking for laser vision correction, such as LASIK. However, I think the solution may not always be laser,” Dr. Harvey says. “For most I think it may be better to use different surgical approaches. It’s certainly a challenge and we always have to think about the associated hidden issues with hyperopia. Sometimes there can be mild amblyopia that’s unrecognized, as well as decreased stereopsis. That’s really important to recognize with a refractive patient long in advance because we have great lasers and lenses but they can’t restore the wiring.”

Dr. Loh notes that hyperopia is a moving target. “Their prescription is constantly evolving and changing,” she says. “Performing LASIK on a mild hyperope is difficult because in a year or two, their lens continues to change and their hyperopia keeps changing, even though you may have corrected them in the moment with LASIK. I’ve experienced referral patients who are only six months post LASIK and are already hyperopic again.”

Visual outcomes are improving, however, as reflected in at least one study that compared hyperopic LASIK performed on a wavefront platform vs. the outcomes on excimer lasers from previous literature.

A total of 379 eyes underwent hyperopic LASIK on the Allegretto EX500 laser and at three and 12 months postoperatively, 66 percent and 69 percent of eyes had a UDVA of 20/20 or better and 96 percent and 97 percent had a UDVA of 20/40 or better, respectively. The mean refractive spherical equivalent was − 0.52 ± 0.78 D at three months and − 0.46 ± 0.79 D at 12 months. At a year, 96 percent of eyes achieved a spherical equivalent within ± 1 D of the intended target. The authors noted a significant difference in UDVA rates of 20/20 or better in studies published before and after 2005: 32 percent vs. 68 percent, respectively. They concluded that the safety, efficacy, stability and accuracy of hyperopic LASIK has greatly improved in the past two decades.5

|

|

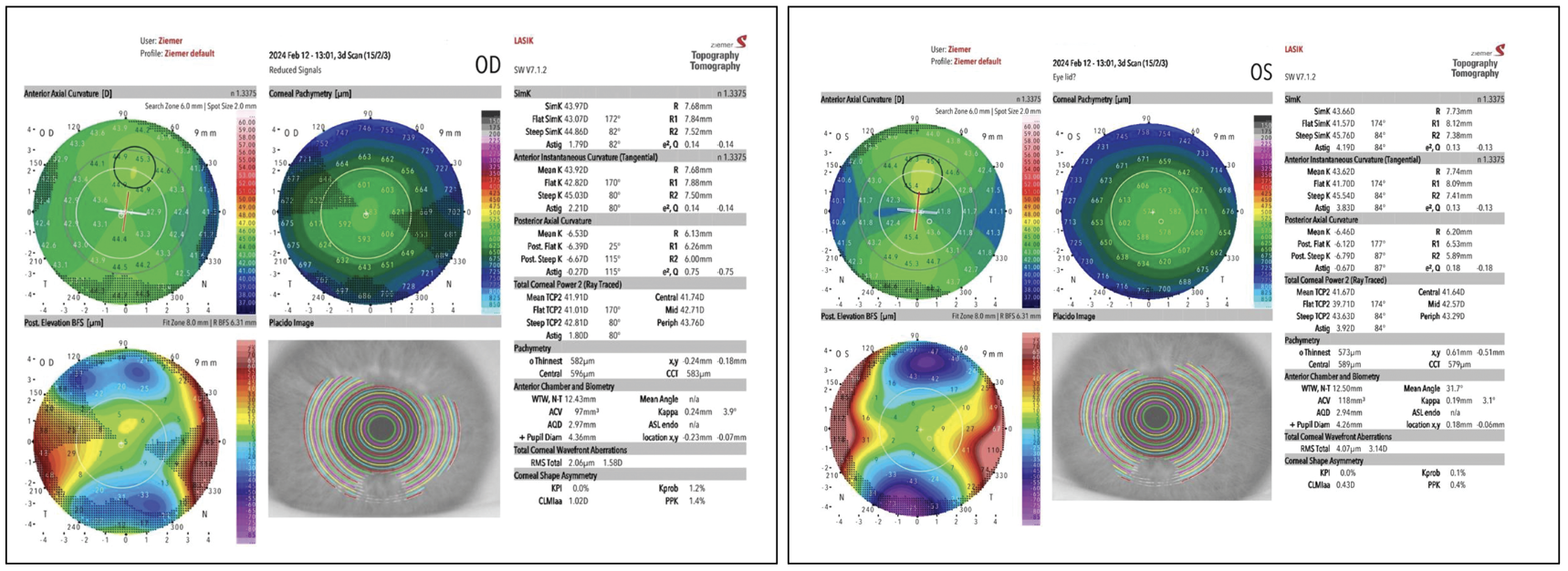

This 43-year-old male patient was interested in spectacle independence. His preop manifest refraction was OD +2.50 -2.25 × 005 corrected to 20/20 and OS +6.00 -5.00 × 173 corrected to 20/25. Although the potential for the left eye was limited, the patient had realistic expectations and was treated with wavefront-optimized LASIK: OD +2.00 -2.25 × 179; OS +5.00 - 4.00 x 173. At two months the patient had 20/15 uncorrected OD and 20/30 uncorrected OS. The patient did report a slight blur in the left eye but said it didn’t affect his life or require additional treatment. His residual refractive error that day was: OD +0.50 -0.25 × 150; OD +1.25 -1.00 × 160. Photo: Thomas M. Harvey, MD. |

Treatment Considerations

It’s well-known that, whereas myopic patients only need corrections to see at distance, hyperopes are more complicated because they require both their near and distance vision corrected. Discussing the patient’s goals can help in the decision-making process, say surgeons.

“You have to look at the patient’s age and needs,” says Peter Hersh, MD, FACS, who is the director of the Cornea and Laser Eye Institute in New Jersey and a clinical professor of ophthalmology and director of the Cornea and Refractive Surgery Division at Rutgers Medical School. “Are they more concerned with distance vision or are they more concerned with close vision?”

Consider younger patients, he continues. “Whereas a 20-year-old who’s +2 will be functioning very well, a +2, 38-year-old is going to start to notice decreased near vision with premature presbyopia, decreased distance vision and will also experience difficulties in their focus because they have to exert accommodative effort at all distances,” Dr. Hersh says. “Now, a lot of these patients will want their near vision as well, and I would say up until around age 50 or so, in those cases, we’ll consider laser vision correction, but often we’ll add a little bit of mini-monovision. For instance, if a patient’s already a +2.5, we’ll do +2.5 on their dominant eye and +3.25 to +3.5 on their non-dominant eye.

“It’s always important when considering monovision or other techniques that you initially make sure that the patient is tolerant of a disparity between their two eyes,” he continues. “For that we’ll use a lens test using a +1 or +1.5 D in a trial frame. If that doesn’t give us a clear-cut enough result then we’ll fit the patient with a plus contact lens (+1.25 D or so) in their non-dominant eye to see if they’ll be tolerant of something like that. In fact, I’ve had very good success using either LASIK or PRK in younger patients with even higher degrees of hyperopia,” Dr. Hersh states. “For instance, I once treated my nephew, who was +6 at age 25 with a +4 PRK and he’s now older and really still enjoying excellent vision.”

SMILE is another technique to consider for patients with hyperopia up to 3 to 4 D, he adds. A study of 374 hyperopic eyes with and without astigmatism reported 81 percent of eyes treated were within ±0.5 D and 93 percent were within ±1 D of intended correction at the 12-month postop visit. Of the 219 eyes with a plano target, 68.8 percent had an uncorrected distance visual acuity of 20/20 or better and 88 percent were at least 20/25 uncorrected at 12 months.6

“As the patient gets older into their sixth and seventh decades, then I think we’re dealing with a lens that really can’t focus at all and if there’s any degree of nuclear sclerotic change or certainly cataractous change, then I would probably prefer a refractive lens exchange,” continues Dr. Hersh.

Dr. Loh takes a more conservative approach and avoids laser vision correction whenever possible. “I typically don’t do laser vision correction (LASIK or PRK) on hyperopes, even though it’s approved,” she says. “I don’t like the ablation profile that it creates. Often, I noticed the ablation patterns were somewhat irregular; they tend to change a little bit over time and, again, combined with that and the changing hyperopia, patients can be dissatisfied. You usually end up having to do monovision on them to achieve a reduction in glasses use for distance and near and it may not be an ideal situation for the patient.”

She opts for a refractive lens in most cases. “There are a lot of surgeons who will do hyperopic LASIK and it seems to work for some people but again, my concern is the longevity of it,” says Dr. Loh. “I explain that to patients. If a patient’s in their 40s or 50s, I think it’s probably better to do a refractive lens exchange because that way you’ve removed the issue of the continued changing prescription due to the evolving lens dysfunction issue. You’ve taken out their lens and you’ve created a stable refractive profile.”

But what if a patient is insistent on having LASIK? “I usually discourage it,” she continues. “I tell them about the risks and benefits. I’ll recommend they wait a few more years until there’s a better solution. I’d consider LASIK if someone was a mild hyperope and they really understood the risks, but I want them to understand that they’re going to spend money and potentially in six months to a year not be happy if their prescription changes. They also have to be willing to undergo a monovision treatment in order to reduce the need for glasses in most situations.

|

|

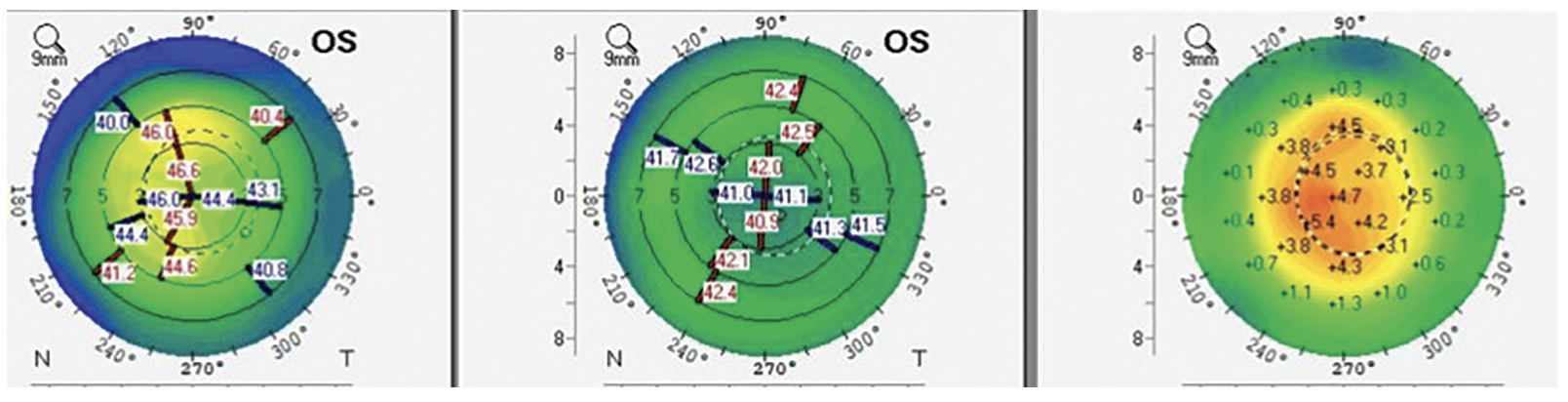

Although performing LASIK on hyperopes can be challenging, outcomes are improving. Surgeons say it’s important to take time to discuss expectations with patients to find out which is more important to them: distance or near vision. Mini-monovision is a technique often used in these patients, but a trial run should be conducted to ensure the patient’s tolerance. Photo: Peter Hersh, MD, FACS. |

“I also don’t want to give them a hyperopic treatment and then in 15 to 20 years when they need cataract surgery they’re no longer candidates for a multifocal,” Dr. Loh says. “I’m pretty cautious for those reasons.”

This is where patient education is really important, says Dr. Harvey. “Generally the lasers we have in the United States do a pretty good job of correcting normal corneas up to +3 D. However, we have plenty of corneas that are either already too steep or are irregular and that would push us into other options, such as refractive lens exchange that works in a variety of situations,” he says. “This is off-label and should only be done by experienced surgeons and those who have good rapport with the patients and have educated them about all the risks that go along with intraocular surgery. This is a discussion that usually starts in the presbyopia age. I’m not doing refractive lens exchange on those who are pre-presbyopic, unless their refractive error is so massive and they’re effectively outside the range of accommodation anyway.”

Dr. Harvey has several IOLs in his arsenal. “For those who have minimal astigmatism and require a power less than 3 D, I’ll choose a ClearView 3 multifocal IOL (Lenstec) to give the patient correction not only for distance but also intermediate and near,” he says. “When there’s astigmatism and the patient requires some element of presbyopia correction with it then I’ll frequently lean on the Symfony OptiBlue IOL (Johnson & Johnson Vision) at this point in time because it does offer a pretty broad range of compensation for corneal astigmatism. That’s nice because with these astigmatism-correcting lenses that have EDOF-multifocal optics, they can benefit from the larger central optical zone present in the Symfony group of IOLs.”

“When I do refractive lens exchanges, I want to make sure the patient is a candidate for a multifocal lens because they’re young and that’s what they’re coming in for,” explains Dr. Loh. “They’re expecting to be glasses-free. To do that you usually need a multifocal. Another option could be the Light-Adjustable Lens or Light-Adjustable Lens Plus and do a blended monovision. You’d of course have to make sure that they were a monovision candidate by either the history of monovision or a contact lens trial in the office, but that’s another option as well.”

Dr. Harvey isn’t sure if the LAL is right for this population. “The problem I see with the LAL is just the logistics of having a patient who’s a young working person having to come back to the clinic multiple times for dilated exams with refraction and adjustments,” he says. “And ultimately the lock-in is for a long time—for the rest of the patient’s life—and these patients are frequently only 40 years old. For these reasons, we haven’t been using that lens in the RLE population.”

Discussions might even include procedures that are approved in other countries, continues Dr. Harvey. “Sometimes we have people who are looking to be glasses-free with everything, but we know that the hyperopic-presbyope is perhaps better served to have refractive lens exchange or a hyperopic phakic lens implantation overseas (that may or may not offer some presbyopia correction). When we have patients who are slightly younger and outside of the respective manufacturer’s sweet spot for hyperopic LASIK, then that can be used a lot more frequently,” he says.

“We occasionally have patients who are on the +4 D and above spectrum that just can’t bear contact lenses, can’t afford a refractive lens exchange and are willing to accept a mild amount of potential contrast impact to have a better refractive error when not wearing glasses/contacts,” Dr. Harvey says. “We’re living in a pretty global world and it’s not a ‘big ask’ for those appropriate patients who are younger to have a hyperopic phakic IOL overseas. For U.S.-based surgeons, we have both Canada and Mexico as our sites for referral.”

Ocular Pathology

Before proceeding with any treatment, surgeons say careful attention should be paid to screening for any ocular pathology, especially dry-eye disease.

“It’s important to note that these patients frequently get bad dry eye with laser vision correction because we’re ablating so far in the periphery,” says Dr. Harvey. “You shouldn’t ablate a preoperative dry eye and then expect the patient to be happy postoperatively because laser vision correction will make them a lot drier at least for a year.”

“It’s extremely important, especially if one is considering a lens exchange for refractive correction, or any of the corneal procedures, that the corneal surface be in pristine condition,” notes Dr. Hersh. “The reason is that any perturbation of light coming through will scatter light rays and cause aberrations. If they don’t have a perfectly smooth corneal lens, it can result in visual static. In combination with a procedure that’s working by making a cornea hyperprolate in the case of an EDOF lens or a multifocal lens, the optical result isn’t going to be good. So we’d have to perform a thorough analysis of the tear film, treat any blepharitis, certainly treat any basement membrane dystrophy. In fact, I think we’d prefer using a PRK procedure on hyperopes with epithelial basement membrane dystrophy because that in essence corrects two things: It smooths the surface, removing the EBMD, and also corrects their hyperopia or presbyopia at the same time.”

Dr. Hersh recommends an in-depth examination of the ocular surface including staining, measuring tear breakup time, looking at the lids for blepharitis or meibomitis, checking the tear film for osmolarity and other indicators, and treating the patient beforehand, especially for patients who are 50 or older.

The other area of concern is the retina. “If one is considering either a corneal procedure or a lens exchange procedure, especially in patients who are getting on in years, it’s very important to do a good macula assessment because any changes that one might have in the retina are going to lead to a poorer result,” Dr. Hersh says.

Managing Patient Expectations

Every refractive surgeon knows the delicate balance between choosing the right procedure and making patients happy, and it’s important to have these conversations in advance.

Dr. Hersh bluntly tells patients that perfect vision isn’t always likely. “No matter what we do, there’s always going to be a compromise between distance vision and near vision,” he says. “The better we get their distance in both eyes, the more they’re going to need reading glasses, so there are trade-offs and the patient needs to make a decision. Do they want to optimize distance, do they want to optimize near or do they want something in between?”

Patients also have to understand aberrations that may result from changing the corneal shape or implanting IOLs. “Such aberrations can cause effects, such as diminished quality of vision, glare, halo and monocular multiplopia, for example,” Dr. Hersh says. “I explain it to them by comparing the situation to a TV. If we take their eye and we do a procedure and get every ray in perfect focus for distance, they’re going to have excellent distance visual acuity just like a high-definition TV. If there’s some irregularity of the surface that might be induced from a corneal or lens procedure, that will add a little bit of aberration or what we call visual static, somewhat like an older TV. Certainly if there’s any significant irregularity that occurs, that can be like a much older TV because it could be a lot of static.

“But I do tell them nowadays the risk of glare, halo and monocular multiplopia are far less than in the early days,” he continues. “However, the important thing is to have an understanding, especially as you get older, about your near and distance function because it’s not really possible to get vision at age 55 like you had when you were 20. There’s always a trade-off between distance and near vision if you don’t want to use glasses.”

Dr. Loh says treating hyperopia has become an art in some ways. “It really depends on the age of the patient, and this is what I’ve been learning,” she says. “It’s really critical to check preoperative uncorrected near vision in these patients undergoing refractive lens exchange because if they’re still in the early part of the journey to presbyopia, there’s a chance that even with the current technology of multifocal lenses, they may not be 100 percent satisfied with their near. Although they might end up being J1 or J1+, which we’d think is a success, they’ll still say it’s just not as good as they expected.

“I learned this from my colleagues as well,” continues Dr. Loh. “It probably is better to be a little more cautious and make sure that these patients are in the more moderate to advanced presbyopia stage because then they’re really going to appreciate that difference and that improvement.”

Dr. Harvey suggests speaking to patients about the alternatives to LVC or intraocular surgery. “I think that some of the presbyopia-correcting drops do offer the ability to temperize things a little bit and perhaps delay surgery temporarily until patients have reached a more suitable age,” he says. “That’s something that can be really helpful. When meeting with hyperopic patients, it’s also an opportunity for them to become educated about contact lenses. Many of them are extremely hesitant to try contact lenses, as opposed to myopes who seem to ‘eat up’ contact lenses like they’re going out of style. With appropriate education and training, hyperopes can actually benefit and learn about some of the advantages of multifocality, too.”

Ultimately, chair time is essential, says Dr. Loh. “The most important thing when dealing with hyperopic patients and refractive surgery is lots of education: understanding their needs; understanding their desires; understanding where they are in the presbyopia journey,” she concludes. “Usually they’re coming to us in their 40s and 50s thinking they’ll just get LASIK. You have to be willing to spend time discussing and educating them on other options.”

Dr. Harvey is a medical monitor for Lenstec and a consultant with Johnson & Johnson Vision and Visus Therapeutics. Dr. Hersh is a consultant for Allotex. Dr. Loh is a consultant and speaker for Alcon, Bausch + Lomb and Johnson & Johnson Vision.

Dr. Chayet is considered a pioneer in refractive and cataract surgery, and is the medical director of the Codet Vision Institute in Tijuana, Mexico. He is a clinical investigator for RxSight, LensGen and ForSight Vision6.

1. Vitale S., Sperduto R.D., Ferris F.L., 3rd Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971–1972 and 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:1632–1639.

2. Hyperopia. https://eyewiki.org/Hyperopia. Accessed May 29, 2024.

3. Kohnen T. Advances in the surgical correction of hyperopia (editorial). J Cataract Refract Surg 1998;24:1–2.

4. McGhee CN, Anastas CN, Jenkins L, et al. The surgical and laser correction of hypermetropia. In: McGhee CNJ, Taylor HR, Trokel S, Gartry D, eds. Excimer lasers in ophthalmology: Principles and practice. London: Martin Dunitz 1997:273–94.

5. Moshirfar M, Megerdichian A, West WB, Miller CM, Sperry RA, Neilsen CD, Tingey MT, Hoopes PC. Comparison of visual outcome after hyperopic LASIK using a wavefront-optimized platform versus other excimer lasers in the past two decades. Ophthalmol Ther 2021;10:3:547-563.

6. Reinstein DZ, Sekundo W, Archer TJ, Stodulka P, Ganesh S, Cochener B, Blum M, Wang Y, Zhou X. SMILE for hyperopia with and without astigmatism: Results of a aprospective multicenter 12-month study. J Refract Surg 2022;38:12:760-769.