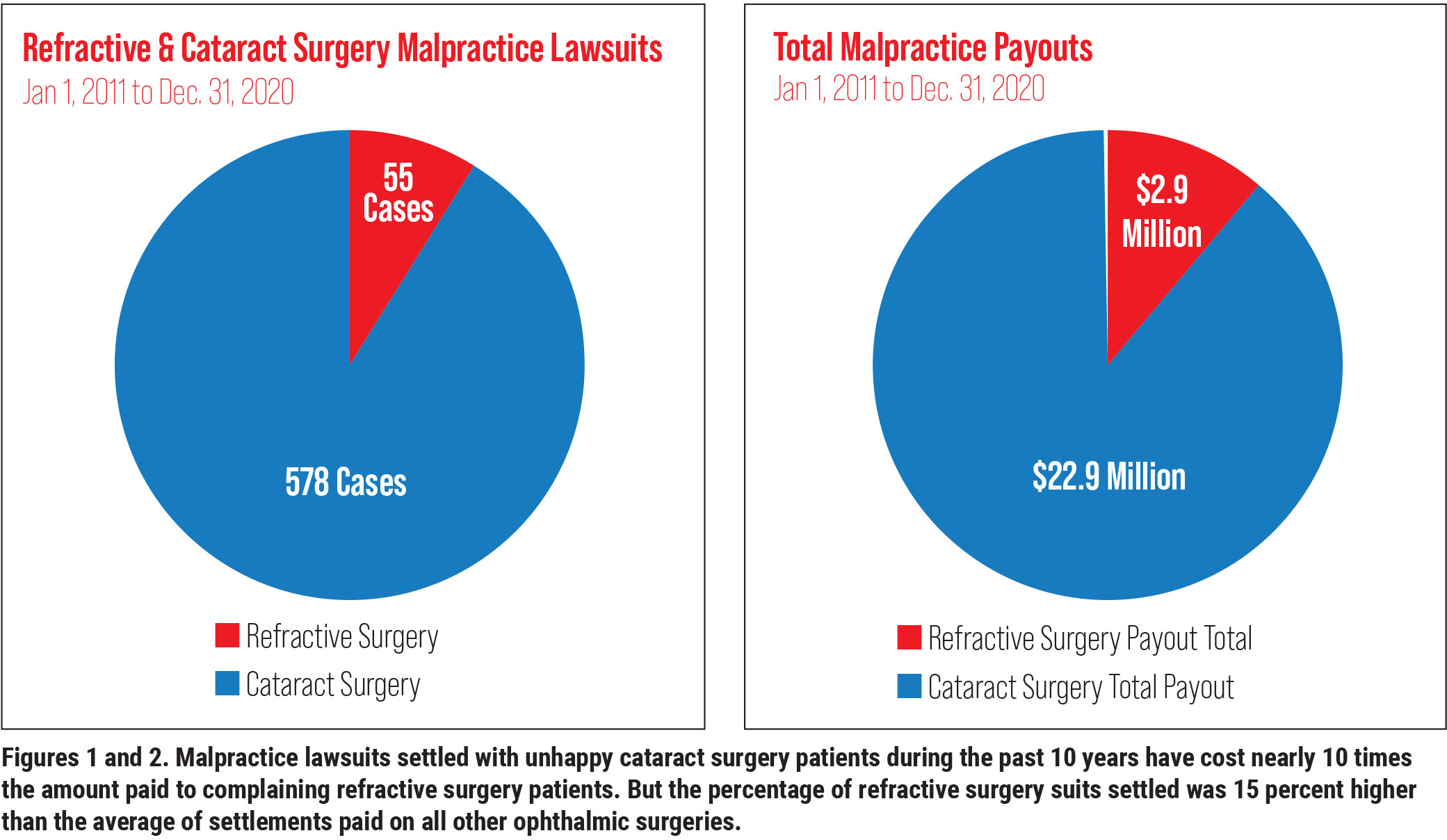

During the past 10 years, 578 malpractice lawsuits related to cataract surgery have been filed, while only 55 have been brought for refractive surgery, according to Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company statistics. These numbers represent a fraction of the tens of millions of cataract and refractive surgeries performed during this span. However, experts who defend eye surgeons against legal action say the low numbers are no reason to let down your guard.

The experts urge you to take time-tested preventive measures to make sure you’re not someday included in this exclusive but very unhappy club. “Having a suit filed against you is an experience you want to avoid if at all possible,” says Gregory Tiemeier, Esq., of Tiemeier & Stich in Denver, a firm with decades of experience defending ophthalmologists in court. “The problem is that, if you get sued, you’ve already lost, whether you win the case or not. It’s going to take a tremendous emotional toll on you and your time. It’s very much a distraction and can be damaging to your reputation in the community, depending on the size of that community.”

In this report, you’ll learn what typically constitutes a complaint and how to minimize the threat of one by correctly obtaining informed consent. You’ll also find out ways to spot a potential suit and learn strategies you can use to effectively manage cases that might lead to a lawsuit.

First: The Numbers

Between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2020, OMIC recorded 21 settlements of refractive surgery lawsuits, adding up to $2.9 million in total payments to plaintiffs. Payouts ranged from $10,000 to $300,000. Although the average payment of $138,000 was relatively low⎯compared to $245,000 for all ophthalmic surgeries, the proportion of refractive surgery cases that resulted in settlements was relatively high, at 35 percent, compared to an average of 20 percent for all cases managed by OMIC.

For cataract surgery litigation, 119 cases (21 percent) led to settlements, totaling $22.9 million. The average cataract surgery settlement was for $192,865. The settlements for cataract surgery ranged from $3,000 to $1 million. There were three $1 million settlements, plus one at $900,000 and another at $600,000.

Following are insights designed to help you prevent your liability company from having to pay any of these costs, based on the experts’ responses to seven key questions.

1. Anatomy of a complaint: How does one get started?

Hans K. Bruhn, MHS, risk manager at OMIC, based on in San Francisco, says a complaint that could lead to a malpractice lawsuit begins as an incident in which a patient is unhappy about the care received. The patient may associate the problem with a lack of prudent care by you, raising key questions:

- Was the care appropriate?

- Did it meet the standard of care?

- Was the care provided in a timely manner?

“A complaint can then follow as a result of the patient’s perception of these issues,” says Mr. Bruhn. “If that complaint isn’t managed or mitigated by the physician implementing risk-management advice and strategies, the complaint can escalate to a claim. This could be an allegation of negligent care and a written demand for money, or a lawsuit filed in the courts. Once a claim is filed, the incident involves an attorney, expenses and lot of the physician’s time.”

2. Is deficient informed consent often to blame? What can surgeons do better?

“The short answer is yes, deficient informed consent is often to blame,” says Mr. Tiemeier. “In my experience, cataract and refractive surgeons usually create a pretty good electronic paper trail of informed consent. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the patient has received adequate information to give informed consent.”

Mr. Tiemeier explains: “The recorded informed consent often shows that the surgeon has had a staff member review the surgery with the patient and provide a consent form. The staff member says: ‘Here. Look this over and let me know if you have any questions. If you don’t, you can sign it and get it back to me,’” he says. “Sometimes, the patient will take the form home, read it and have a conversation with the surgeon or staff member the next day, discussing risks, benefits and alternatives associated with the procedure. Sometimes, however, the conversation takes place with the surgery scheduler. Nowhere in these cases will it show that the surgeon had any discussion with the patient, except perhaps on the day of surgery, when he asked the patient if he or she had any questions.”

Mr. Tiemeier says he can often defend a surgeon in this situation, even if the patient says he or she wasn’t given a chance to read the consent form. “Most juries will think the patient should’ve taken the time to read the form if they signed it,” he says. “But sometimes, more than a signature is needed. You should strive for what OMIC calls a therapeutic alliance, with the doctor and the patient working as a team to overcome pathology.”

Patients are often examined and referred for surgery by a co-managing optometrist, he notes. All preoperative exams and measurements may be completed (either within or outside of a practice) by someone other than the surgeon.

“If you don’t see the patient until the day of surgery, you really haven’t established an underlying sense of trust or therapeutic alliance. Most of the time, everything works out. If something doesn’t go right during surgery, though, you’ll find yourself apologizing and regretfully explaining what went wrong to a stranger. You may never have really talked to the patient, and the two of you are already in a conflict before you start the first conversation. That’s a bad way to start a therapeutic alliance.”

Mr. Tiemeier acknowledges that creating a therapeutic alliance requires extra time in your schedule and may not contribute to an efficient business model. “As the surgeon, you have to make the decision that works best for you and your practice,” he notes. “How much time do you want to spend with the patient to build a rapport?”

To safeguard against these developments, Mr. Bruhn says you often need to strengthen the consent process. “The physician may say, ‘I’m going to do cataract surgery and it’s going to involve these risks,’’’ he says. “The patient says he or she understands. But what the patient understands may be completely different from what the physician is communicating. At OMIC, we strongly recommend that the physician confirm that there is an understanding of what is expected. For example, the physician can say, ‘We’ve talked about the complications that may occur. Do you understand the way that this complication might affect your daily life, if it occurs?’ Or, ‘Are you comfortable with the possible time it will take to recover from surgery or treatment, especially if there is a complication?’”

Some physicians add into the consent form an area in which the patient’s expectations of surgery or treatment are noted, in the patient’s own words. Clarify these to ensure the patient’s expectations are reasonable before asking the patient to sign the consent form. “You want to make sure the informed consent process confirms reasonable patient expectations,’’ notes Mr. Bruhn.

|

3. How does a malpractice lawsuit affect a surgeon and his or her practice, including reputation and confidence?

The effects on your practice reputation, morale and psyche are potentially devastating, experts say. Ryan Busci, vice president of claims at OMIC, says expert ophthalmologists retained by OMIC will comb through the documentation and clinical details of your case, from the preop exam and planning to final outcome. The aggrieved patient’s attorney will also hire one or more experts to closely look at your case for mistakes and oversights.

“If they haven’t been involved in a lawsuit, ophthalmologists might not know or fully appreciate all of this,” says Mr. Busci. “But if they have been involved in a lawsuit, they’re never going to forget it.”

OMIC offers guidance to affected doctors on how to cope with litigation stress. “When someone has accused a physician of negligence, it’s a very personal matter,” says Mr. Bruhn. “A lawsuit can be a great stressor on all who are involved. The practice entity can be named in the suit, adding to those impacted. Because multiple parties can be named in a lawsuit, this can expose multiple limits of insurance, increasing the potential money paid to resolve a claim.”

A lawsuit against you will also emerge as public information when it’s filed, he notes. And, if the lawsuit is settled or a verdict paid on behalf of the physician, this information must be reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), a repository of medical malpractice payments. “This is why, in risk management, we work hard to prevent a suit from being filed,” says Mr. Bruhn.

Once a claim is paid, it has the potential to damage a physician’s reputation. “Sometimes, information about a claim is shared on social media, or criticisms of a physician are posted,” says Mr. Bruhn. “It’s not easy to see that information about yourself on Facebook or some other social media platform. It’s a public forum, but because of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, a doctor can’t even acknowledge that the person who’s complaining has been his or her patient. All you can do is recommend the person contact the physician’s office for a private discussion.”

4. How can you recognize the potential for a lawsuit?

“You can definitely identify the potential for a lawsuit,” says Mr. Tiemeier. “Some patients are going to be unhappy with an objective satisfactory outcome. And that has to do with shortcomings they have in their lives generally. They are often depressed, for example.”

Technicians and doctors are typically not surprised by who files a lawsuit. “Watch for a patient who is particularly demanding or who never seems to be happy with anything that you do,” says Mr. Tiemeier. “If a patient doesn’t communicate well and seems defensive or prickly, proceed with caution. You don’t have to operate on these patients. But you need to be really careful with your charting, using free texting in your EHRs to explain why you don’t think surgery is advisable.”

Mr. Tiemeier recalls one case involving a highly myopic patient with a long-standing cataract who experienced a retinal detachment in his good eye. The cataract was removed, despite the threat of another retinal detachment. “The surgeon did a very good job of documenting every visit while educating the patient on the risks of a very complex procedure,” says Mr. Tiemeier. “Patching and additional surgery were required. The careful documentation made the case very defensible. I had another case of an 11-D myope, whom the surgeon tried to correct with LASIK. There was absolutely nothing in the chart before or even after surgery about the risk of LASIK in a high myope creating the high potential for a flap complication.”

Another patient in Mr. Tiemeier’s case files was a high myope and a bond attorney who couldn’t read small type to do her job for months after LASIK. “You need to carefully consider a confluence of clinical, medical, personality, occupational and lifestyle factors before doing any procedure,” he says.

Another sign of increased risk, says Mr. Bruhn, is when patients can’t decide whether to undergo a procedure and tell you they’ll get back to you. “The patient may say he or she wants to check with another doctor,” says Mr. Bruhn. “This may be fine because, obviously, second opinions are always welcome. But there’s a point when the patient’s indecisiveness and even incorrect perceptions should signal to you that there’s potential for a problem. Ask yourself: Given the patient’s current attitude, how will the patient act after a surgical complication? The case might be hard to manage.”

|

5. What common liability traps should you be aware of?

From a clinical perspective, Mr. Busci says the most common problems that lead to settlements in refractive surgery are faulty preop exams. “This can occur when doctors don’t recognize that some patients aren’t suitable candidates for a procedure,” he notes. “Cases of missed keratoconus are prevalent. Sometimes, doctors just don’t recognize that a patient has a cornea that’s not appropriate for refractive surgery.”

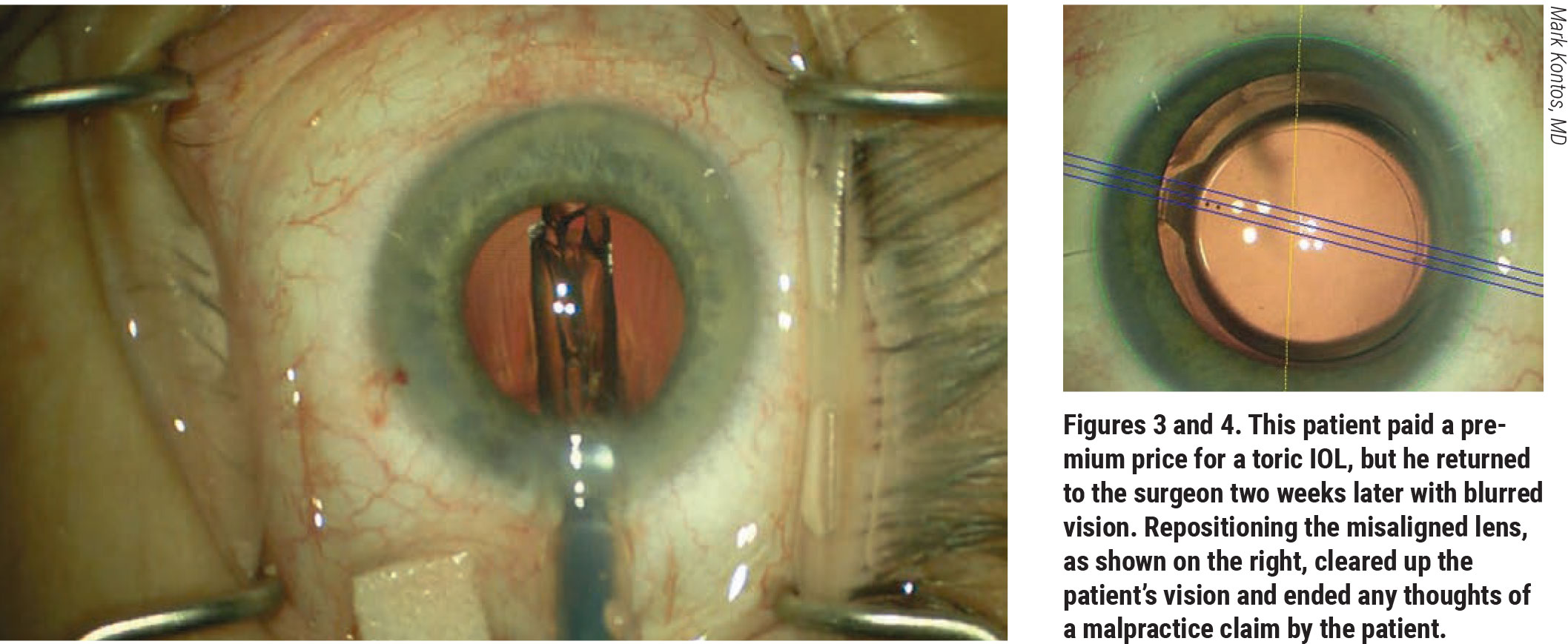

For cataract surgery, Mr. Bruhn says the choice or power of an IOL can lead to patient dissatisfaction. “For example, we’ve had patients complain that they didn’t select a toric lens, even though the documentation clearly shows that the patient selected that lens,” says Mr. Bruhn. The discussion and documentation need to go beyond the risks, benefits and potential complications. “This is typically handled by the physician and the scheduling coordinator at the office,” he points out. “For refractive surgery, it’s crucial to discuss patient expectations and the healing process.”

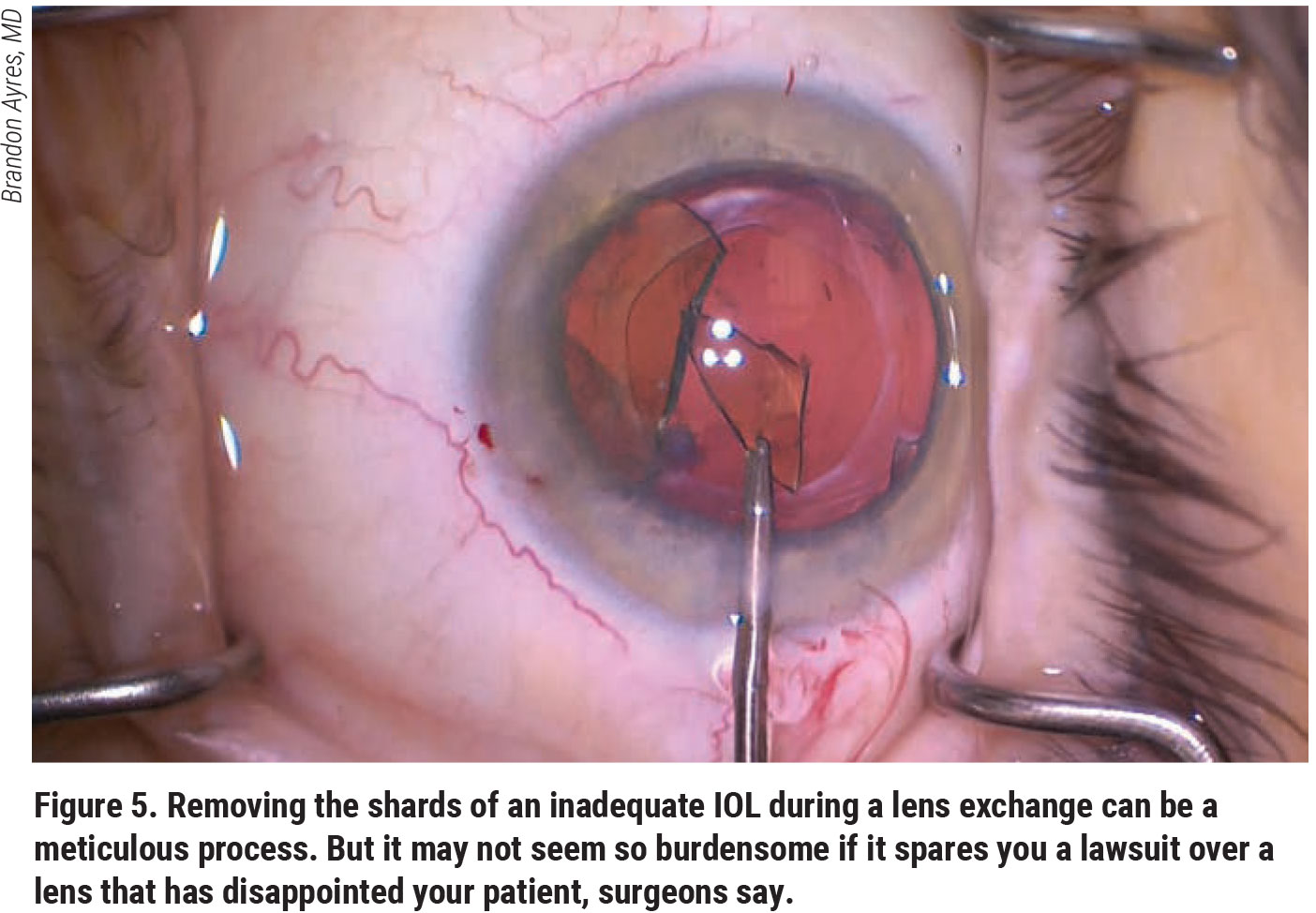

Mr. Busci notes that his company has seen a noticeable uptick in complaints and lawsuits related to the implantation of premium IOLs in recent years. How does he recommend reducing risk for these cases? “I believe many cataract surgery lawsuits come from unrealistic expectations about the capabilities of these high-technology lens implants, including the unrealistic expectation that every patient will be independent of the need for glasses postop,” he says. “The use of high-technology lenses in inappropriate candidates who have underlying corneal or retinal diseases can be another problem. Informed consent and tempering patient expectations is important preoperatively.”

Mr. Tiemeier says you should emphasize to your staff that every patient is different, even though the procedures are all the same. “Lack of awareness of the unique findings, characteristics and care plans of each patient is especially a problem when it shows up in the electronic health records,” he says. “Because of time constraints, your staff may pre-populate these records without much thought before the patient even walks into the room,” he notes. “Often things that should be changed are not. I don’t believe I’ve tried a case in three years without the electronic health records being at least part of the trial. Typically, the problem is caused by a carry-forward function conveying information from a previous exam that the technician hasn’t deleted. For example: The record says, ‘Discussed risks benefits and alternatives with the patient.’ That’s great if it appears prior to surgery. When it appears in the records for a visit after the surgery and the visit after that and the visit after that, the jury starts wondering if the surgeon ever actually had that conversation or if this was just the record being pre-populated with those words every time the patient visited the practice. That creates a credibility problem that can undermine the defense of the surgeon.”

6. What’s the best way to respond to an unhappy patient?

Mr. Bruhn recommends a prompt response. “The patient’s dissatisfaction can grow if you don’t respond to concerns,” he says. “The physician may be reluctant to engage further or may not know how to engage. It’s important that communication continue, however. The doctor should get his or her liability insurance company’s advice and respond to the patient right away.”

He notes that a complication doesn’t necessarily represent negligent care. If there was an error, the patient should be told immediately. The message should come from the operating surgeon. “If disclosure isn’t handled promptly, a records request can reveal that something wasn’t done correctly,” he points out. “Discovery of an undisclosed error can create a perception that there was an attempt to hide what occurred. Continuing communication and responsiveness are very important to minimize risk.”

Refunds can be used to mitigate risk. “Discuss these situations with your professional liability carrier,” advises Mr. Bruhn. “Sometimes, it may be appropriate to have the patient sign a release confirming that the refund has resolved the issue. At OMIC, a release is drafted by an attorney for that patient.”

|

7. How can you and your staff minimize or avoid a lawsuit?

Making sure you and your staff remain vigilant throughout a case is important, Mr. Bruhn says. “If a patient’s not coming in for a follow-up appointment and repeatedly cancels appointments, that’s not a good sign,” he notes. “In these situations, the doctor needs to reach out and follow up with the patient to correct this non-compliant behavior. Staff may be the first to identify an unhappy patient in this situation rather than the doctor.”

Because refractive surgery is often an elective procedure, paid for out- of-pocket by the patient, you should be careful during preoperative discussions, according to Mr. Bruhn. “When a patient is paying out-of-pocket, his or her expectations can go up,” he points out. “It’s important in these situations that expectations are reasonable and attainable. The patient needs to understand that surgical outcomes can’t be guaranteed. Surgery is complex and has risks. In some cases, there may be a need for additional care. The discussion with the patient prior to surgery is critical.”

If a patient is uncertain and doesn’t seem like a good candidate for a procedure, Mr. Bruhn recommends that you reconsider surgery. “If there are concerns, it’s best to hold off on surgery,” he says. “Seeking a second opinion may help a patient with a decision to consent to surgery.”