Alison Early, MD, a medical and surgical comprehensive ophthalmologist including cataract and refractive surgery at Cincinnati Eye Institute, has been practicing for approximately six years and in that time she’s already experienced musculoskeletal discomfort. In fact, she first noticed it as a resident.

“It wasn’t something that anybody inquired about or asked me or even talked about at all,” Dr. Early recalls. “I remember thinking maybe it’s the chair that I’m sitting in or the computer height or something, but I didn’t really pursue it any further. I think that there’s a culture throughout medical school residency fellowship that it’s hard, it’s uncomfortable and you’re sort of rewarded for pushing through difficult things. And frankly, a lot of our equipment isn’t really designed with the user ergonomically in mind.”

After observing Michael Snyder, MD, who is an ophthalmology professor at the University of Cincinnati, in the operating room, Dr. Early noticed how he discussed proper ergonomics and positioning during surgery. It was the first time she’d heard someone else mention the issues she was dealing with. However, as her career in private practice began, the tightness in her back, neck and shoulders was noticeable at the end of each day.

“I learned that it was something very commonly encountered by ophthalmologists, and not just us, but lots of people in similar careers—dentists, head and neck surgeons, and people who spend a lot of time looking through microscopes,” continues Dr. Early. “We all assume similar positions and repetitive postures, which lead to what are called cumulative strain injuries. So it’s not necessarily a large-scale motion that causes you to throw your back out in a dramatic way, but this repetitive motion over and over and over and over again, all day, every day for weeks, months, years, decades that can actually really affect the longevity of your career and yourself.”

This issue of musculoskeletal disorders and chronic pain among ophthalmologists and microsurgeons has been studied, with self-reported rates of 50 percent1 in a 2005 study of nearly 700 ophthalmologists in the Northeast, and more recently, smaller studies have shown rates of 66 percent2 and 81 percent.3 Severity and frequency of pain has led some surgeons to reduce their operating time and clinic hours.2

Some within the field see this as an emerging epidemic that requires awareness and education in order to save the next generation of ophthalmologists. Many accomplished cataract and refractive surgeons are sharing their own personal experiences, as well as the posture and equipment modifications they’ve made to find relief.

“Sam Masket, MD, has been really at the forefront,” says Dr. Early. “I think in his position as a very widely known and well-respected career ophthalmologist, for him to have been as open as he’s been about the issues that he’s had (sharing his own spinal MRI images and publishing in journals), it’s really eye-opening. For him to sit where he is with his perspective and gravitas and to encourage people to start addressing this early, I think it does carry a lot of weight.”

|

|

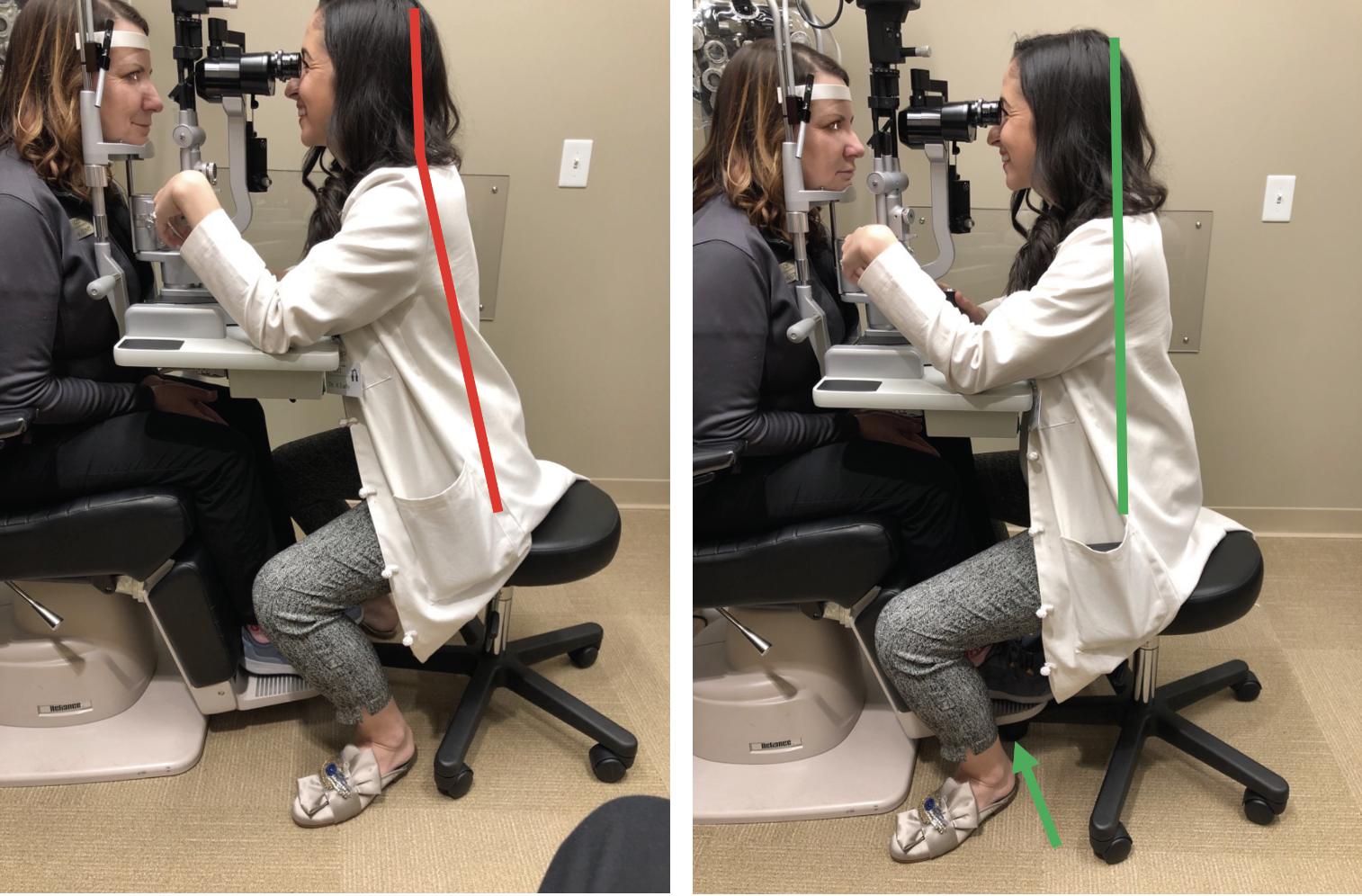

The slit lamp is one of the main sources of complaints from ophthalmologists who often lean forward at an uncomfortable angle to examine patients. Above, Alison Early, MD, demonstrates the adjustments she made to create a more neutral spine while sitting at the slit lamp, including elevating the patient’s chair and moving closer to avoid leaning. |

Common Culprits in Ophthalmology

It’s evident that the contributing factors to the chronic pain experienced by ophthalmologists is a combination of repeated positions and movements, along with ill-designed equipment.

In 2015, Deepinder K. Dhaliwal, MD, LAc, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh, slipped on water in the operating room. She developed a severe L5, S1 disc herniation and became disabled. She tried everything she could to avoid having surgery, including physical therapy, acupuncture, meditation, as well as pain medication and use of an interferential current stimulator device, which she would use right before operating. Ultimately, she persevered through the pain without surgery, but did a deep literature dive into musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmology.

One of the most common culprits cited is the slit lamp. “The slit lamp is a huge one,” Dr. Dhaliwal says. “What we do is we crane our neck forward to get closer to the patient—we’re leaning forward all the time. That’s terrible.”

Steven G. Safran, MD, who’s a comprehensive ophthalmologist in private practice in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, says it was a medical issue of his own that alerted him to the harm the slit lamp was causing to his body. It started with a visit to the chiropractor for an adjustment due to lower back pain. Dr. Safran subsequently broke out with shingles in the area and neck pain that wasn’t there previously. Another adjustment led to numbness and pain on his left side. An MRI revealed severe disc damage of his C5-6/C6-7. As a solo practitioner, Dr. Safran struggled to keep up with his patients, working through the pain. He eventually underwent surgery in 2016, but healing the nerves took two or three years.

“When this was going on I became acutely aware of the things that were exacerbating the problem, because what you can tolerate when you’re healthy, you can’t tolerate when you’re not healthy,” says Dr. Safran. “It was then that I started to realize that my slit lamp tables and leaning into them for exams was harmful. It’s almost impossible to have good posture and if you have a head-forward position, it puts a lot of strain on your back and upper back muscles, leading to repetitive injury to the disc and vertebrae.”

Dr. Early also noticed how the slit lamp put her body into an awkward position. “As a cataract and refractive surgeon I see usually between 40 and 50 patients per day, and I’m doing fairly thorough examinations on all of them at the slit lamp,” she says. “Slit lamps are wonderful, but their design hasn’t changed much in at least the last half century. They’re really not ergonomically designed for either the patient or the examiner and the chair that the patient sits in positions them in a slightly reclined position. That sets up the examiner to be leaning more dramatically forward. The issue that I had was when I was in that position, my trapezius and upper spine and neck were very sore at the end of the day because I was essentially in an abnormal neck extension all day to look through the microscope oculars to examine patients. My seat or stool was behind me so my hips were flexed and my neck was extended, which caused a lot of the load bearing to be in my thoracic and cervical spine.”

The indirect ophthalmoscope is another uncomfortable piece of equipment, adds Dr. Dhaliwal. “It’s super heavy and there’s something called ‘text neck.’ Text neck comes from flexing your neck forward to look at your phone, which you should never do. However, that’s becoming an epidemic and truly it can wreck your spine,” she says. “With the indirect, when you think about it, we’re flexing our neck forward with a heavy weight on our head. If the human head typically weighs 10 to 12 pounds, when you flex it forward about 45 degrees that increases the effective weight of your head close to 50 pounds. If you go 60 degrees, that’s an effective weight of 60 pounds. And then when you add the weight of an indirect it’s very heavy. Even if you don’t have the indirect on your head, just flexing your neck forward changes how much effective weight your cervical spine has to support.”

It’s not just MDs who are noticing occupation-related pain, notes Dr. Early. “I’ve spoken to career ophthalmic technicians who have shoulder issues, which once they become aware of the possibility of cumulative strain injuries, they realize this is probably from moving the phoropter in front of the patient 30 to 40 times a day for decades and their one shoulder will be affected or they’ll have issues with grasp and grip leading to carpal tunnel and radial neuropathy because of all the gripping and twisting and holding lenses and fine finger movements,” she says.

Chairs and sitting posture should be considered, too, says Dr. Dhaliwal. “Sitting is really problematic because when you compare it to lying down, sitting puts 250 times as much pressure on the intervertebral discs as compared to lying down,” she says. “Standing is much better. That puts 100 times as much pressure on your disks, believe it or not. If you’re having back problems, lying down is the best thing in order to relax your spine, but obviously we can’t do that easily at work.”

Dr. Early actually realized that her office attire was somewhat dictating the way she could sit while examining patients. “Prior to the pandemic I was always in business-professional clothing, often in heels, dresses, skirts, which basically forced me to twist my spine to examine patients,” she recalls. “I’d be seated in a side-saddle position, which of course is not a neutral spine. As a result of the confusion and concern about contact spread at the beginning of the pandemic, I started wearing scrubs so that I could change immediately upon arriving home, and it helped in a number of ways. I’ve continued to do this and I’m able to focus on positioning myself in a positive ergonomic posture.”

|

|

In the OR, Alison Early, MD, prioritizes positioning herself properly with a neutral spine and relaxed shoulders, as opposed to extending her body to reach the equipment, which can lead to injury. |

Adjustments to Consider

Each of these surgeons we spoke with have made both small- and large-scale modifications that they say contributed to marked improvement in their pain and overall well-being. Here are a few of their suggestions.

• Slit lamp. A miniscule change helped Dr. Early. “What I found was that just by essentially removing the barrier of the patient’s foot rest, either by elevating the patient’s chair maybe a half an inch to an inch, or just folding the foot rests out of the way, that allowed me to move my chair forward closer to the patient so that my body could be closer to the slit lamp, my spine to be in a neutral upright position, and my neck to be in a neutral upright position,” she says. “Almost instantaneously making that very minor change, which probably takes two to four seconds for patients, nearly immediately resolved that discomfort that I was having.”

“I like to have a straight posture with my ears over my shoulders, my shoulders over my hips and my neck is straight,” says Dr. Dhaliwal. “I raise the patient’s chair and I slide my chair under the patient’s footrest. I have the patient sit near the forward edge of the chair so they’re actually perched much more forward, and then they lean into the slit lamp so I stay straight. Actually, they’re much more comfortable, especially women who sometimes have a hard time getting close enough to the slit lamp. I’m never hunched over.”

Of course there will be patients who are unable to accommodate these adjustments, but it’s still worth doing for the majority of your other cases, notes Dr. Early. “If you’re in your proper posture 90 percent of the time, you can meet a patient who has physical limitations the other 10 percent of the time and it’ll take a much longer period of time for you to experience issues related to that small fraction of patients,” she says.

Dr. Safran’s slit lamp modifications were a bit more intricate and actually involved redesigning his whole table. Working with a patient who was a carpenter and cabinet maker, Dr. Safran’s new design puts his oculars flush with the edge of the table, enabling him to sit up straight without craning his neck forward. The slit lamp table is also rounded and smooth to support his elbows without being painful.

|

|

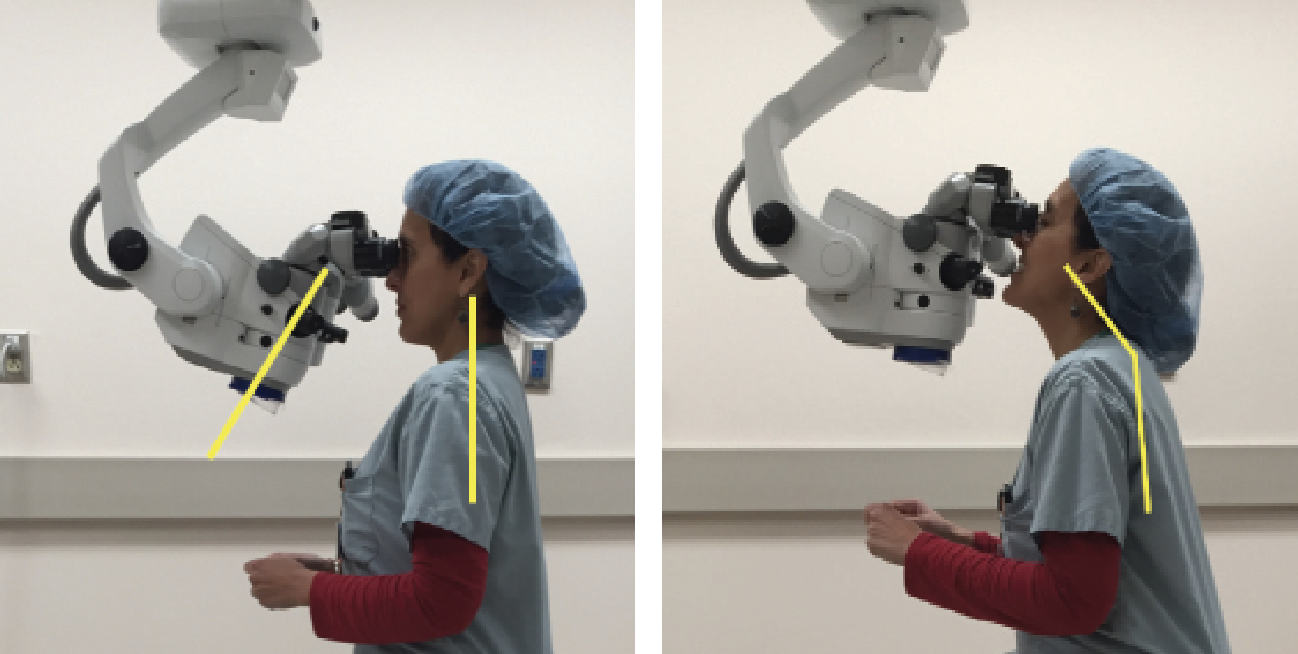

Poor posture at the microscope (left) can lead to musculoskeletal discomfort and cause severe damage to the spine over time if uncorrected. As Deepinder Dhaliwal, MD, LAc, demonstrates (right), adjusting equipment to your body is a simple modification that can make a big difference. |

“The tables really made it possible for me to continue practicing because I don’t think I would have been able to continue when I was having this problem in the first year or two after my surgery,” he says. “I don’t think it would have been possible for me to see patients using my old table.”

Since then, Dr. Safran has lent his input to Haag-Streit in their creation of a line of slit lamp tables (without financial interest). One suggestion was to allow headrest straps to be switched out. “Longer straps allow the patient’s head to be closer to the doctor, even a half inch or one inch closer makes a difference,” he says. “If the headrest strap is shorter then it’s going to be tighter and push the patient’s head back away from you.”

Although Dr. Safran prefers his own table, he and other ophthalmologists are glad to see industry responding to these issues.

“We need industry to really change the way we do things and we need to be able to operate safely and effectively with new tools so that we can decide when we want to retire and we are not forced to retire due to disability,” says Dr. Dhaliwal.

• Indirect ophthalmoscope. To resolve her issues with this equipment, Dr. Dhaliwal says she now raises the patient’s chair up as high as it’ll go and then performs a dilated fundus exam while keeping her neck straight. “It’s changed my life,” she says.

• Operating room. “The OR chair is really important,” adds Dr. Dhaliwal. “The key is that the chairs should have good lumbar support, allow our legs to be comfortable under the surgical bed and allow us to look through the operating microscope without craning our neck.”

Chair and operating tables don’t always sync up either, and the microscope is a third element to adjust, says Dr. Early. “I operate with a traditional operating microscope and my goal is to position myself first, use the lumbar support, spinal support, neutral spine position, neutral neck, and then bring the patient into position and into focus,” she says. “That’s helped me a lot through long operating room days.”

An alternative, which has become quite popular in modern operating rooms, is actually using a 3D Heads Up operating suite, continues Dr. Early. “That can potentially eliminate the positioning with the microscope oculars and gives the surgeon a much more ergonomically friendly position in the OR,” she says. “For those who do have access to that, I think that’s a wonderful investment for a practice to make in their surgeons over the long term.”

Although it’s a step forward, Dr. Dhaliwal believes the 3D Heads Up may still put strain on the neck. “You have to turn your neck to see the screen. It should be straight, so it’s not the best position,” she says.

Dr. Safran says he didn’t modify equipment in the operating room, per se, but he did modify what was going on between his ears. “I modified my awareness of my posture,” he says. “I like to meditate and there are many cultures with chair meditation techniques and certain posture: your ears are positioned over your shoulders, head in line with the spine, shoulders back and lower back curved forward with your knees angled downward slightly. I try to emulate this in the operating room. I straddle a banana seat with my knees lower than my hips and I sit up straight. I don’t use back support.”

An OR setup should be built to suit each individual surgeon, says Dr. Dhaliwal. “There are challenges for people with shorter torsos and longer legs—like me,” she says. “I have to tilt the scope more in order to be comfortable, not extend my neck and be able to fit my legs underneath the surgical bed. You really have to do a deep dive into making sure your surgical setup is comfortable in order to operate effortlessly and, no matter how many cases you’re doing, not end the day in discomfort.”

She suggests it might even be a good idea to consult physical and occupational therapists. “Truly we should be inviting them into our ORs and offices to assess our posture and make recommendations,” Dr. Dhaliwal says.

• Core strength. Knowing how to strengthen your core is very important for every microsurgeon. “The multifidus muscle goes along the spine and that’s really what you want to strengthen,” Dr. Dhaliwal says. “When you do that, you’re able to really support your spine so that you’re less prone to injury.”

Dr. Early agrees. “A lot of people overlook the importance of having a strong core, but as an ophthalmologist, especially a surgical ophthalmologist, when you’re operating you’re using both hands and both feet and your core is really what’s responsible for stabilizing your entire body when all of your limbs are in use,” she says. “Being physically active in your everyday life, focusing on a healthy strong core—your abdominal muscles and your anterior core as well as your posterior core and spinal muscles—is really critical to just setting yourself up for success in being able to sustain the career longevity that we all want.”

Awareness in Young Ophthalmologists

There’s hope that these lessons can be passed on to ophthalmologists who are just starting out before it’s too late.

“Younger ophthalmologists may just take some of this discomfort as par for the course,” says Dr. Early. “Medical training and residency is difficult. It’s uncomfortable, we’re sleep deprived, it takes a toll on our bodies, but you don’t always feel like you have the license to look out for yourself when you’re a trainee. I think it’s really important for trainees to be aware of it, for residency programs and fellowship programs to be aware of it and try to encourage the residents and fellows and young career doctors to take care of themselves in ways that aren’t just sleep, hygiene and healthy food and things like that, but actually caring for your body as you go about your workday is really critical.”

Dr. Safran says it’s hard for young people to think that far ahead to their later years and how their actions now will affect them. “It’s like someone who smokes when they’re young, and then they get to age 60 and realize it wasn’t such a great idea,” he says. “Young ophthalmologists may not feel the need to be concerned about their neck when they’re young, but if they want to be better surgeons, having good posture will make them better.”

Dr. Chayet is considered a pioneer in refractive and cataract surgery, and is the medical director of the Codet Vision Institute in Tijuana, Mexico. He is a clinical investigator for RxSight, LensGen and ForSight Vision6.

1. Dhimitri KC, McGwin G Jr, McNeal SF, Lee P, Morse PA, Patterson M, Wertz FD, Marx JL. Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139:1:179-81.

2. Schechet SA, DeVience E, DeVience S, Shukla S, Kaleem M. Survey of musculoskeletal disorders among U.S. ophthalmologists. Digit J Ophthalmol 2020;31:26:4:36-45.

3. Tan NE, Wortz BT, Rosenberg ED, Radcliffe NM, Gupta PK. Digital survey assessment of factors associated with musculoskeletal complaints among U.S. ophthalmologists. Clinical Ophthalmology 2021;15:4865-4874.