Cataract surgeons will often come across patients with Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy as well as cataract. The progressive nature of Fuchs’ leads to corneal decompensation and vision loss, and it’s important to investigate whether their symptoms are due to Fuchs’ or to cataract, and the severity of the disease, before determining the appropriate treatment path.

Staging Surgery or Combining It

In the presence of milder Fuchs’, if your clinical judgment is that the cataract is a bigger contributor to a patient’s vision problem, removing the cataract may result in a significant improvement in vision. However, if the patient has central guttae and they’re visually significant, you can consider combining cataract surgery with Descemet’s Stripping Only procedure with or without a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, if you have access to them. Studies have shown ROCK inhibitors promote corneal endothelial cell proliferation in vitro and migration in vivo.1

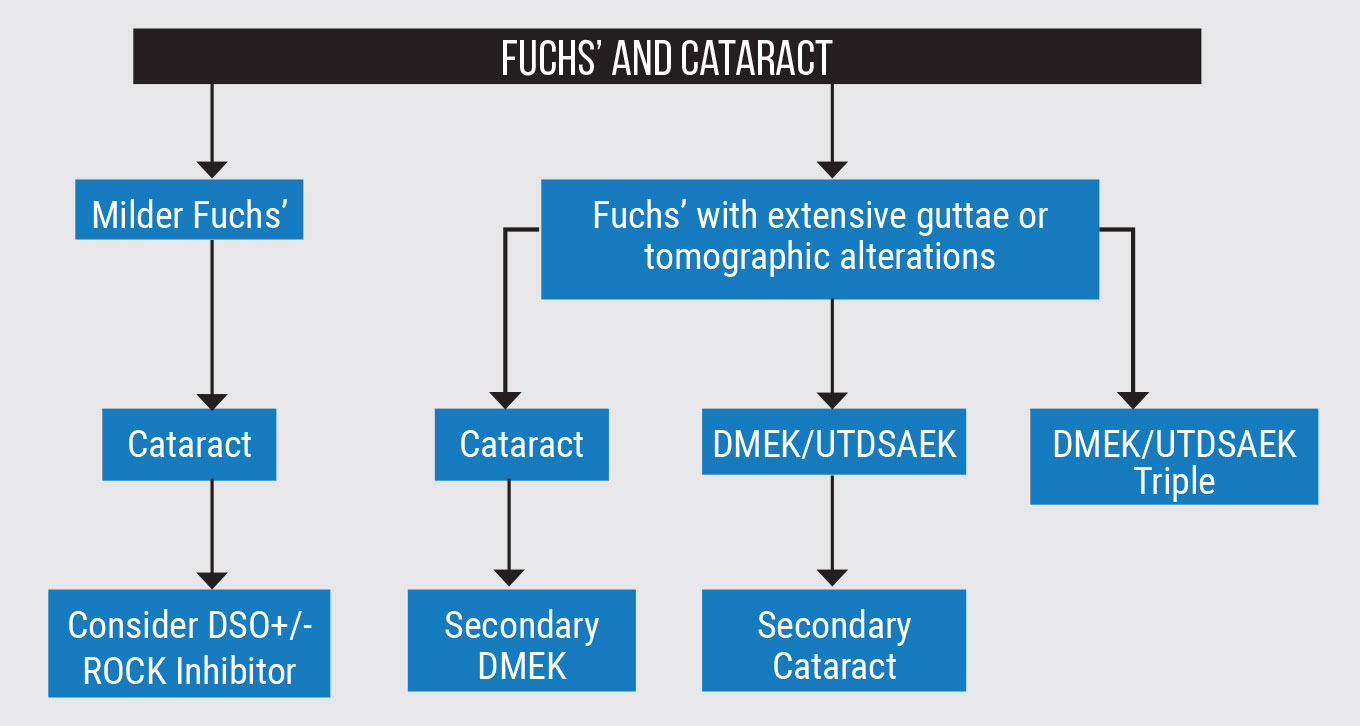

When a patient has more extensive guttae, there are three classical pathways a surgeon may consider for this scenario, including staged surgeries or combined procedures (Figure 1). The first steps in staged treatment could be cataract first, followed by Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty vs. DMEK/Ultrathin Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty first and cataract second.

There are advantages to each. If you perform cataract surgery first, the subsequent DMEK and IOL stabilization may be easier. DMEK first has numerous advantages and, in my opinion, it’s easier to do DMEK on a phakic eye and you may have a better view to the IOL afterwards.

The third approach is combining DMEK/UTDSAEK with phaco. This approach probably accounts for most of my surgeries in such cases. Many patients prefer having only one surgery, but we have to take certain variables into consideration.

If the cataract isn’t very dense but the guttae are dense in the center, then we might deduce that a bigger proportion of that is attributed to Fuchs’ and a smaller portion of that is cataract, which would probably drive us to consider doing the transplant. But then we have to ask ourselves: Should we do the cataract at the same time?

One of the reasons to hold off on cataract surgery is that, if we normalize the cornea first, we actually get it into a more natural state, after which we may achieve a better refractive outcome during cataract surgery. When we combine the cases we tend to get surprises in the refraction. Nowadays, surgeons generally assume in their calculations that a majority of patients are going to shift in the farsighted direction, so they aim a little bit nearsighted on the lens. I would say that works across the population on average fairly well, but there are patients that shift in the opposite direction.

|

We did a randomized controlled trial looking at this and we actually found that about 38 percent of patients shifted nearsighted in that trial.2 Because we aimed nearsighted initially, patients ended up more nearsighted than we wanted them to be. There are probably a number of variables driving that—most of them have to do with how the posterior and anterior shape of the cornea change as a result of corneal transplant surgery.

In our trial, we also discovered a dip in the total corneal refractive power at three months, which then reversed partially at six months and 12 months.2 We believe there may be a redistribution of endothelial cells at the edge of the graft where there’s more damage, causing central thinning faster and then a slight steepening because of redistribution in the periphery. I’d like to see enhanced variables that allow us to predict—based on a patient’s grade of Fuchs’ or based on their preoperative topographic features—how that cornea is going to change in response to having a DMEK/DSAEK surgery done. This would help us to better predict what lens power we should put in the eye to appropriately match that.

When you consider these factors, an argument could be made for staging the surgery. But of course, if we staged the surgery, we’re doing two things: we’re exposing the patient to potentially additional risks with two surgeries, and we’re exposing them to the risk of damaging the graft after they’ve healed. It may not be a major threat for most skilled cataract surgeons, but we don’t have long-term data to know if grafts actually do a little bit more poorly over time after staged surgery due to the additional trauma from cataract surgery.

The Impact on Lens Calculations

We know that changes after endothelial keratoplasty aren’t immediate—they take time. This is a challenge if you’re staging patients. The data suggests that the cornea isn’t stable yet even if it’s clear, and that the cornea will continue to change its shape for six to 12 months after surgery. This raises the question of the appropriate timing for the cataract surgery. I don’t think we have a good amount of evidence to answer that question yet, but the evidence we do have suggests that you might want to wait at least six months. This is relevant for new lens technologies, including the Light Adjustable Lens from RxSight. Once it’s in the eye, the lens power can be changed, which makes it very appealing for eyes with corneal findings—post-keratoplasty, keratoconus or previous radial keratotomy. We can potentially put that lens in and shift its power up to 2 D on label, probably a little bit more off label, in either direction if we’re off.

It’s not a perfect solution, though. The problem with a changing cornea in a Fuchs’ patient is not knowing if that cornea will drift out of that correction, because once you put the LAL in and adjust it, it must be locked in place. After that, it can’t be adjusted again. Surgeons may decide not to lock it in place until the cornea stabilizes, but that requires the patient to wear UV-protected goggles (per FDA Label) full time until they’re adjusted and locked in. It’ll be a little bit trickier to determine when that optimal stablization point for the cornea is in patients with endothelial keratoplasty. They’re going to have to wait longer and accept some sort of a UV protection for their eyes if they go down that path.

DSO with or without ROCK inhibitors is a growing procedure among transplant and cataract surgeons. There’s some retrospective data from Greg Maloney’s group (Australia) suggesting that there may be a mild myopic shift in patients that undergo DSO vs. the hyperopic shift we see after DMEK or DSAEK. This could be because, in those particular patients, the cornea swells centrally, which causes a central bulging or steepening of the cornea and that could increase power in the cornea. This complicates lens calculations.

Personally, I tend to favor conventional IOLs in Fuchs’ patients. I don’t usually use toric lenses in these patients because the change in toricity in the cornea is a little less predictable, although the data suggest that it’s not the toricity change as much as a change in total corneal power. Total corneal power can affect any lens choice you pick, but if you select a toric lens and the total corneal power changes, then you might be off in two directions—astigmatically and from a basic spherical equivalent standpoint as well, causing the patient to end up more nearsighted or farsighted.

I also avoid multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus lenses in my patients. I know some surgeons are advocates of that, but I feel there’s too much unpredictability in a combined surgery to actually get the refractive outcome that the patient would expect when they’re paying out of pocket. You might also degrade the optics in the eye a little bit in some of these patients by doing a multifocal or an EDOF lens because of aberrations in the cornea.

There’s some emerging data on the LAL, and even though it’s not published yet, I think we’re going to see some positive results from this. Surgeons are going to have to wait for data that gives us a little bit of guidance on when to adjust that lens or when to put it in. If we combine the cataract and DMEK or DSAEK, we’ll need to prepare our patients to wait awhile to get that adjustment, or we’re going to have to perform the endothelial keratoplasty and come back and put the LAL in three to four months later, and then consider doing the adjustment at five to six months, depending on the stability.

Even if they’ve undergone DMEK, we can’t treat Fuchs’ eyes as necessarily being optically equivalent to a normal cornea, since that can lead to refractive disappointment, which could then require lens exchanges, or just a lot of postoperative counseling. Surgeons need to be mindful of the choices they make. They’re under pressure to provide the best refractive outcomes for patients and, often, that leads them to make decisions that aren’t in the patients’ best interests and choose a premium lens that won’t deliver. Even after endothelial keratoplasty, the cornea may be more aberrated than it is in a normal situation.

Preoperative Imaging

Many surgeons still rely on specular photomicroscopy to grade Fuchs’. I feel specular microscopy in its current form is probably inadequate because the images it generates are central corneal images, and that’s where the guttae are most concentrated. It makes it difficult to get an accurate idea of cell count or cell morphology with central guttae. Some of my peers have referred to it as a ‘random number generator.’ Others have argued that looking at corneal thickness may suggest the level of disease, but in general, there’s a lot of variation in corneal thickness in patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy and that’s probably also misleading in terms of determining the health of the cornea as well as for making a decision. There have been some papers that argued if a cornea is over a certain thickness then you should do endothelial keratoplasty as well—I think that’s outdated information, however. There are better ways to look at the health of the cornea specifically by looking at tomographic changes.

One technology that’s going to emerge over the next few years is the use of next generation OCT to better characterize isolated layers of the cornea preoperatively. We currently see value in broader maps of the cornea using the newly approved Optovue Solix OCT-A (Visionix). We’re prospectively looking at our Fuchs’ patients pre- and postoperatively to see how their corneal OCT maps change as a result of surgery. Total pachymetric maps as well as stromal and epithelial maps as imaged by OCT may return to normal after DMEK based on pattern standard deviation analysis (a method that has been used for years to assess changes in visual field maps). So OCT may be a tool to predict features of corneas preoperatively that allow surgeons to determine whether we should do transplants at the same time as cataract surgery.

Emerging into the mainstream is some of the work that’s come out of the Mayo Clinic, specifically from Sanjay Patel, MD, and his group, looking at changes in corneal tomography with Scheimpflug imaging.3 They looked at preoperative features of the cornea that may predict significant deformation or changes in the cornea as a result of Fuchs’, namely the loss of circular isopachs, which reflect a bulging in the back side of the cornea as a direct result of swelling from Fuchs’.

|

|

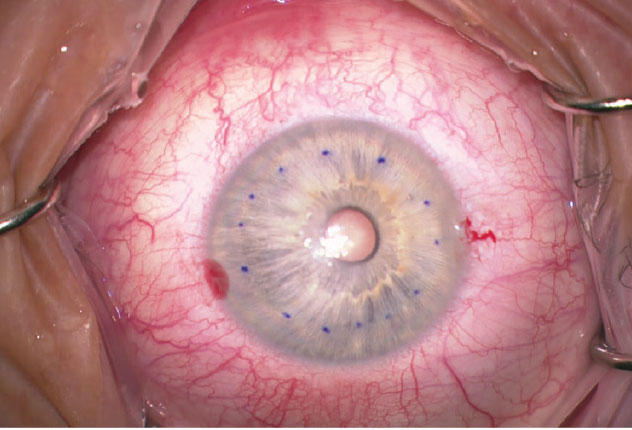

This 64-year-old male patient presented with Fuchs’ and cataract with central corneal guttae and a few small bullae centrally. He complained of foggy vision lasting until noon. I performed phakic DMEK first to normalize the cornea and his visual acuity went from 20/30 to 20/20 at three months postop. Cataract surgery was performed approximately one year later. |

Scheimpflug imaging can give you a map of the corneal thickness over a large area, and that thickness gradually increases as you move peripherally and the colors change similar to what we see on topography, but the colors on a pachymetric map actually represent changes in thickness as you go from one region to the next. We expect these to be relatively normal in a normal eye with circular changes, but in an eye with Fuchs’ often what we see is a distortion of that pachymetric progression. We see some of the thinnest points will be more off center now because the cornea is actually swelling centrally from the guttae. We see a displacement of that thinnest center point and then we see a loss of regularity in those isopachs and sometimes they appear more D-shaped or irregular. In our own retrospective analysis, what we’ve seen is that if you do DMEK on these patients, those shapes return to normal, which suggests that the endothelial cell function that’s driving those changes is actually driving optical changes in the cornea as well.

In our study, I recommended looking at the posterior curvature of the cornea, which the Scheimpflug imaging is very good at—you can actually see the posterior axial or sagittal curvature map. Cornea surgeons are used to looking at the front map or the average map on the front and the back, but randomized controlled trials have defined that the biggest changes in the cornea as a result of Fuchs’, and also after endothelial keratoplasty, are in the posterior cornea. If we look at the posterior cornea of a patient preoperatively and we see a large irregularity in the axial map, that can be a predictor of what’s actually driving optical problems in the eye and may sway the surgeon to decide to do endothelial keratoplasty first or to combine it with cataract surgery. We also see those irregularities or distortions correct or normalize after endothelial keratoplasty is done, which again is a suggestion that the optical problems are being driven by the endothelial cell layer.

Dr. Chamberlain is a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the division of cornea and refractive surgery at Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. He is an investigator in the Kowa trial.

1. Kinoshita S, Colby KA, Kruse FE. A close look at the clinical efficacy of rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor eye drops for Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Cornea 2021;40:10:1225-1228.

2. Chamberlain W, Shen E, Werner S, Lin C, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Changes in corneal power up to 2 years after endothelial keratoplasty: Results from the Randomized Controlled Descemet endothelial thickness Comparison Trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2023;245:233-241.

3. Sun SY, Wacker K, Baratz KH, Patel SV. Determining subclinical edema in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: Revised classification using Scheimpflug tomography for preoperative assessment. Ophthalmology 2019;126:2:195-204.